The American War Years of Art Nouveau Architect Victor Horta

When Victor Horta was forced to flee during the First World War, his exile became an opportunity to raise funds for poor little Belgium. The famous Belgian architect, who is known for his art nouveau houses, travelled to the United States to give lectures on the German atrocities. During his stay, Horta also became fascinated by skyscrapers and standardised housing. His wartime years would greatly influence his ideas about architecture, urban planning, and society. Horta saw America emerge as a model in the reconstruction of Belgium, as is shown in a book by art historian Tom Packet.

‘Two cars in every garage, a chicken in every pot.’ No Belgian politician would ever have dared to make this kind of election promise in the 1920s, yet it was the slogan with which the Republican Herbert Hoover won the keys to the White House in 1928. In America it was far from a utopian ideal, but rather a plausible aspiration and, what is more, epitomising the self-made mindset.

In a country where economic growth and industrial production were flourishing, luxury and comfort were indeed more affordable and accessible for a wider range of the population (or at least for those who were prepared to work hard). The other side of the coin, however, is that America was perceived by many Europeans as an extremely materialistic country, as a people that excelled in superficiality, as a nation devoid of any culture worthy of the name. Or, as French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau is said to have quipped: America? The only country that went from barbarism to decadence, without civilisation in between.

Victor Horta ca. 1900

Victor Horta ca. 1900© Wikipedia

That seems to have been very much the opinion of architect Victor Horta (1861-1947), when he disembarked for New York on 29 November 1915. In his memoirs, Horta frankly admits that he had never previously intended to travel to America. The country, he said, lured him with little more than the promise of a cheaper life and the opportunity to polish his English.

So why the sudden voyage? To understand that we have to go back in time a few months. Since August 1914, the First World War had been thundering across the European continent. The violent invasion of Belgium by the German army shocked the international community, but Horta decided to stay in Brussels despite all the risks. In February 1915, however, he was invited to attend a reconstruction congress in Great Britain. He left Brussels clandestinely and, in London, condemned the destruction he had encountered in Belgium. ‘It is impossible to believe this devastation was wrought by people’, he said, ‘and not by savage beasts!’

The following day his statement was splashed all across the newspapers, and it could certainly not have been much appreciated by the German occupiers. From then on, Horta’s fate was linked to that of the war itself – as long as the clash of weapons could be heard at the front, returning home was not an option. The few days he had planned to stay in London turned into an exile that lasted several years.

With fellow artists, Horta organised activities in London to raise money for the Belgian Red Cross

Like many other Belgians who had fled, Horta tried to spend his time usefully. In his early fifties, he was beyond fighting age, but there were other ways for exiles to support the national war effort. With fellow artists, he organised activities in London to raise money for the Belgian Red Cross.

Belgian nurse Marie Depage

Belgian nurse Marie Depage© researchgate.net

In the feverish search for funds, people increasingly looked across the Atlantic. The Belgian nurse Marie Depage is the best-known example of this. In early 1915, she undertook a very successful fundraising campaign in the US that she tragically paid for with her life. On 7 May 1915, the Lusitania, the ship on which she was returning to Europe, was torpedoed by a German submarine.

But in London, the image of a generous America remained, strengthened since the start of the conflict when the US had become a driving force behind humanitarian help for occupied Belgium. So, in the autumn of 1915, it was Horta’s turn. With his friend Louis Lazard, the secretary of the Anglo-Belgian Red Cross, and laden with a suitcase full of slides and manuscripts, he set off for the US to raise money by giving lectures on architecture.

Victor Horta was an exceptionally productive speaker, as is clear from the estimated 150 lectures he gave while he was there. His American lectures have never been studied before, yet they tell us a lot: both about Horta’s own vision of architecture and about the way architectural history was viewed in Belgium around the turn of the century. Amongst other things, we see that Horta explained regional differences in Gothic and Romanesque monuments on the basis of contextual factors. In his opinion, an historic monument was very clearly a product of the society that had produced it.

Throughout 1916, Horta took the Americans on an extensive tour through the Belgian architectural landscape

For example, if you think that the Gothic town hall of the French town Arras looks very similar to those of the Flemish town Oudenaarde or Brussels, you are right, according to Horta. Since Belgium’s two largest rivers originate in France (the Scheldt and the Meuse), intense cultural exchange is an obvious consequence. So, throughout 1916, Horta took the Americans on an extensive tour through the Belgian architectural landscape. In the lecture halls of Harvard University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Wellesley College, young students saw idyllic images of belfries, churches and town halls in Huy, Leuven, Mechelen and Antwerp.

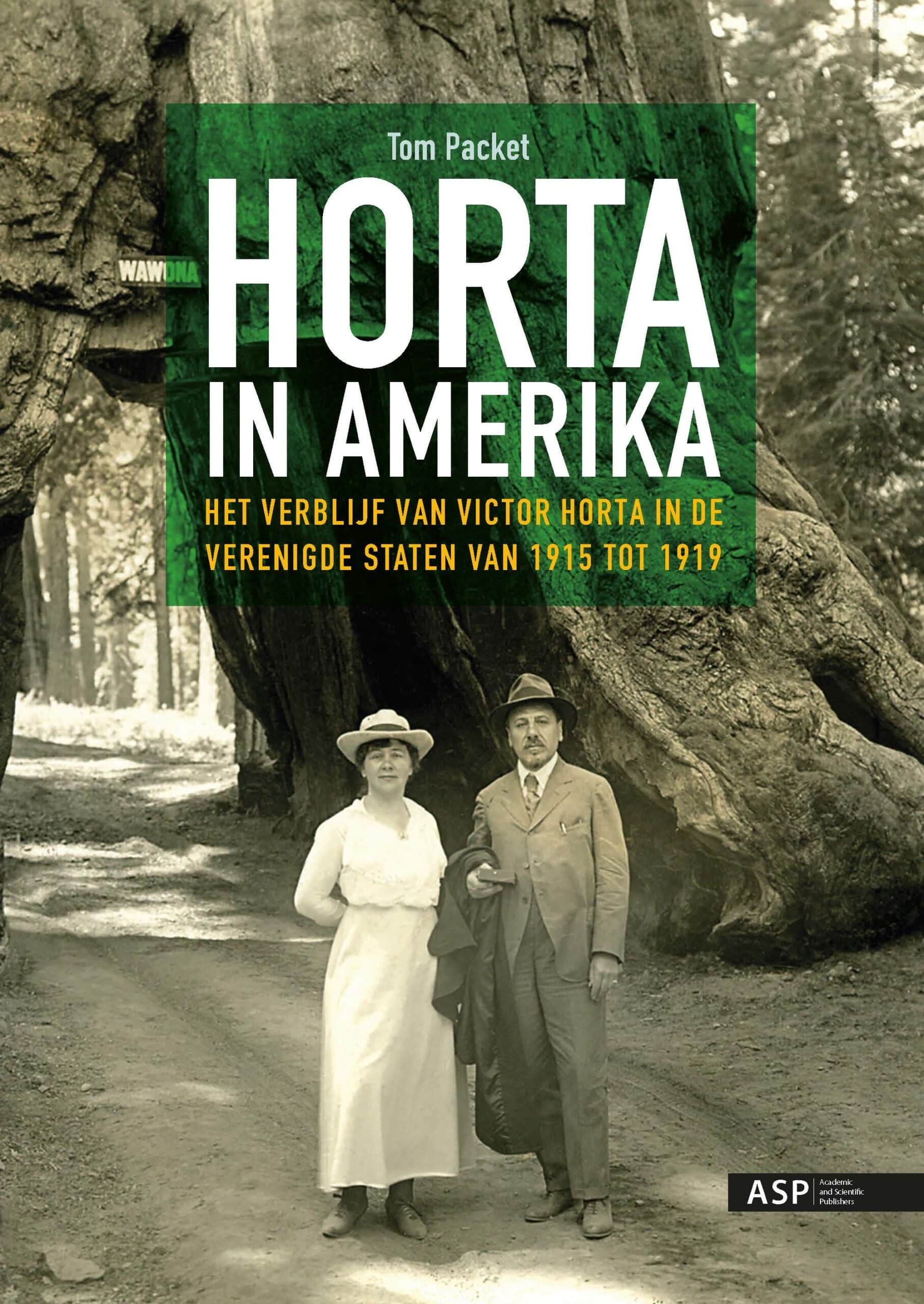

Julia and Victor Horta in Yosemite National Park, California, August 1918

Julia and Victor Horta in Yosemite National Park, California, August 1918© The Horta Museum Archives

The situation changed somewhat in 1917, the year in which America joined the European conflict. Whereas President Woodrow Wilson had initially insisted on the absolute neutrality of American society, from 1917 onwards it was mobilised in its entirety for the war.

Victor Horta adapted his lectures, too. Although his presentations had been extremely diplomatic at first, as of the second half of 1917 his manuscripts were peppered with strong, polemical statements. Obviously, the war was taking a long time, and American enthusiasm had to be maintained. Horta began to focus exclusively on the destruction of Belgian monuments. With photographs of churches and cathedrals that had been shot to pieces, he presented the Americans with a simple choice: that of a free, democratic world or that of brutal autocracy (as symbolised in the destruction of Belgium).

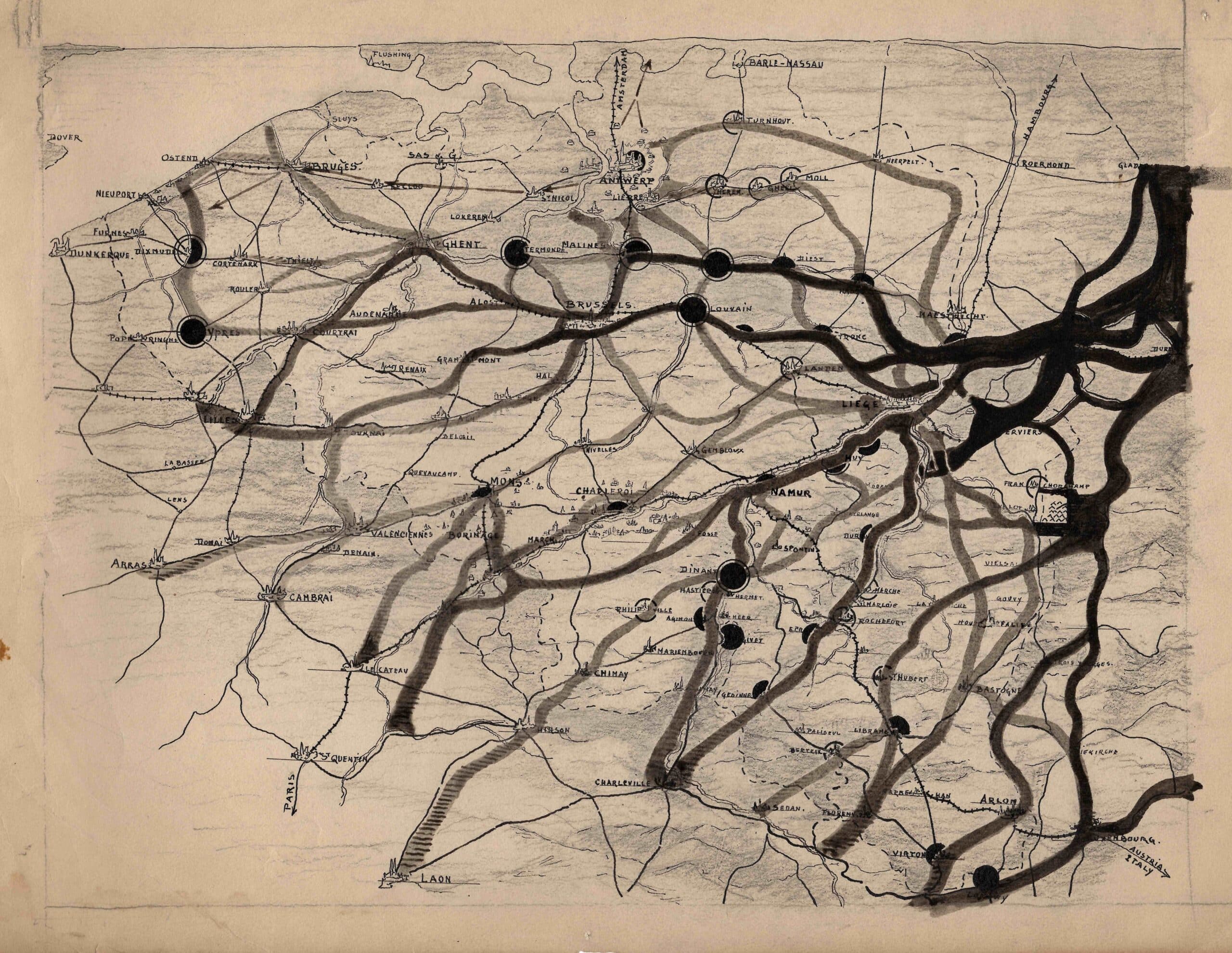

Map of Belgium drawn by Horta, showing the German invasion and damaged, martyred cities (second half of 1917 or first half of 1918)

Map of Belgium drawn by Horta, showing the German invasion and damaged, martyred cities (second half of 1917 or first half of 1918)© The Horta Museum Archives

‘You are fighting against a system that you cannot accept, and you will fight until the end’, he summed up for an audience in San Diego. In the United States, the architect, who was known in Brussels as a big fan of Wagner and had still visited the Werkbund Exhibition in Cologne in 1914, made almost inconceivable statements about the character of the German people and their Kultur, or rather, their lack of culture. But in America, too, the propaganda mill was operating at full speed and Horta had to conform to the whims of public opinion, that much is clear.

The American government systematically presented itself to its citizens and allies as the last bastion of the free, civilised world. The journalist George Creel later described how they took ‘the gospel of Americanism to every corner of the world’. More and more Americans began to see themselves as Europe’s saviour and redeemer, their own society as an example or ideal to be followed (and, of course, a remedy against Bolshevism). The old continent was physically and morally in ruins. In other words, it was America’s turn to step to the foreground.

The neo-Gothic Cathedral Building through Victor Horta’s lens, Oakland, California, 1918

The neo-Gothic Cathedral Building through Victor Horta’s lens, Oakland, California, 1918© The Horta Museum Archives

It was a message that Horta repeated so often that he himself began to believe it. In his memoirs, he wrote how, with the passing of the years, his convictions became less categorical. Gradually, Horta started to see America as a model for Belgian reconstruction, a development that was reinforced by the fact that his lectures took him all over the country. He became absolutely fascinated by American skyscrapers, for example. In Oakland, he photographed the Cathedral Building, the first neo-Gothic skyscraper on the West Coast. (No doubt he also had to get used to the enormous number of cars driving around American cities even then.) Later he collected photos of more recent skyscrapers, including the New York Central Building (1929), designed by the architect Whitney Warren, whom Horta had met in 1915 and with whom he would remain in contact even after his return to Belgium.

The New York Central Building, New York, 1929

The New York Central Building, New York, 1929© The Horta Museum Archives

Horta’s burgeoning fascination with America clearly revolved around more than just architecture. In late 1918 he visited the factories of Armour, in the Chicago Meatpacking District, one of the largest and most modern food producers in the US, where vast quantities of canned foods rolled off the production line. A more telling example of America as a rational, highly mechanised and high-tech country would be hard to find.

Production hall of the Armour Oleomargarine Factory, Chicago, Illinois, ca. 1918

Production hall of the Armour Oleomargarine Factory, Chicago, Illinois, ca. 1918© The Horta Museum Archives

Horta studied the American advertising world as well and praised its drive for overconsumption. (‘It is because Americans buy twice as much as they need, that your industrial life is so prosperous’, he said in Salt Lake City). He researched the construction of motorways and railways and learned about urban planning from the city councils of Chicago and San Francisco. During one of his last interviews with The Seattle Daily Times, Horta did not hesitate to admit that Belgium would be adopting as many American recipes as possible for its reconstruction: ‘We intend to take something from your social life, from your economic life, from your industrial life. Whatever we find useful to our purposes we will take’, the newspaper quotes. In early 1919, when the Hortas were finally able to return home, his wife Julia sighed that it would take another two weeks before Victor could pack up the enormous amount of documentation he had in Washington D.C.

Horta did not hesitate to admit that Belgium would be adopting as many American recipes as possible for its reconstruction

By 1918, the country that had already lured so many Europeans in the 19th century, with promises of freedom and prosperity, clearly had Victor Horta in its grip as well. And, despite the fact that his enthusiasm was somewhat tempered in the 20s and 30s, Horta’s exile was interesting because of the period when it took place. Whereas, before 1914, Europe still turned its nose up in contempt at all things American, the 1920s saw the dawn of American cultural domination.

From that point on, jazz rang out in Brussels bars, Josephine Baker danced the Charleston in Paris, and Hollywood stars dominated the silver screen from London to Berlin. In 1925, the Austrian writer Stefan Zweig criticised this ‘Monotony of the World’, the increasing threat to European cultural identity by the growing American hegemony.

Horta, too, would struggle for a long time with the feeling of being Americanized. In his memoirs, he looks back with a hint of envy at an ‘ascendant America’, vibrant with ‘daring enterprise’ and ‘generalised happiness’. In contrast, when he returned to Belgium in 1919, he found it full of narrow-minded attitudes and limited budgets. It was so difficult or even impossible to realise grand projects that sky-high expectations were doomed to fail. ‘In my opinion, none of these American visions are suitable for our country’, wrote a sombre Horta in 1939. The contrast with his enthusiasm in 1918 could hardly be greater.

Tom Packet, Horta in Amerika, ASP, Brussels, 2021, 228 pages