The Ant That Became a Nit. How Untranslatable is Dutch?

Translators are indispensable passeurs de culture: thanks to them Dutch speakers may discover texts from other language areas and non-native speakers may learn about Dutch-speaking culture. But can just about anything be translated? Are there any Dutch words, concepts and expressions that simply cannot be converted into another language? From mierenneuken

(‘nitpicking’) and gezellig (‘cosy/sociable’) to uitwaaien (‘get a breath of fresh air/a walk by the sea’) and ‘polder model’: translation scholar Goedele De Sterck examines the ‘untranslatability’ of Dutch and possible strategies to get around the issue.

The Van Dale dictionary defines the practice of translation as: transferring from one language to another. Strictly speaking, everything is untranslatable because no two languages and cultures are identical. Each culture has its own reading glasses and perceives and names the world accordingly, so a one-to-one equivalence is by definition impossible. Culture-specific phenomena are often experienced as particularly untranslatable: place names, historical references, government institutions, customs and regional dishes, religious practices and complex abstract concepts that are typical of a culture, country or region-specific world view and outlook on life.

This can be ascribed to the fact that the phenomenon or concept itself, the semantic meaning and often also the accompanying emotional value are non-existent and unknown in the target language and therefore there is no word for it. Examples are the Arabic baraka, the Catalan seny, the Norwegian hygge, the Portuguese saudade or the Indian namaste. In addition, a great many languages encompass diverse cultures, with their own world view, cultural phenomena, and language use. As a consequence, translation problems can also arise within the same language. For example, in the Netherlands the word lopen (‘walking’) can mean ‘going’, whereas in Flanders it can also mean ‘running’. In Belgian Dutch, the word bank is a bench, but may also mean sofa in the Netherlands. Belgians eat fries and croques, and the Dutch eat chips and toasties.

Loanwords as a translation strategy

Such culturally specific matters and phenomena do not pose a problem as long as they circulate within that language and its cultural community. But once they become the subject of conversation in other languages, the lexical gap needs to be filled. Language contact is a phenomenon of all times and all continents. Direct language encounters of the past, in which an often-small group of language users came into contact with a foreign language as a result of trade missions, expeditions, colonisation, war, travel or migration, are today amply surpassed by the indirect contacts that occur via the new mass media.

As a result, many more people are exposed to language contact and therefore inadvertently become translators when they are confronted with a new or unknown phenomenon from another language. In doing so, they are quick to apply an age-old translation strategy: instead of inventing an equivalent in their own language, they adopt the foreign word and turn it into a loanword.

Globalisation ensures that many loanwords immediately develop into internationalisms (words common in several languages, including in Dutch). As the dominant world language, unsurprisingly, English is now the main lender.

The list of English internationalisms covers almost all areas of human life and seems endless: fake news, low cost, Black Friday, burnout, celebrity, USB… These are all things or phenomena that, together with their term in English, have conquered large parts of the world. This enhanced, intensified and accelerated cultural exchange also promotes contact with other foreign languages. For example, feng shui (Chinese) has become an indispensable part of the design of living and working environments. Halal (Arabic) is firmly ingrained in international vocabulary. We have all tasted kimchi

(Korean) and edamame (Japanese). And who wouldn’t be thrilled by the duende

(Spanish) of an Andalusian flamenco show?

All these international loanwords appear regularly in Dutch-language books, newspapers, magazines, and websites and on that basis have been added to the Dikke Van Dale dictionary in recent decades, which means that they have truly become part of the Dutch language. The Van Dale Loan Dictionary (2005) mentions 12,751 loanwords. Like all other languages, Dutch consists largely of untranslated foreign words that have become fully established over time and have lost their strangeness. Who still recognises the foreign origin of Dutch words like avocado (1770, Spanish avigato), duister (1350, Russian tusk, ‘darkness’) or walrus (1594, Swedish hvalross

or Danish hvalros)?

And vice-versa? Does Dutch export phenomena and words to other languages as well? For the answer to this question, we can consult Nicoline van der Sijs, who edited the publication Nederlandse woorden wereldwijd (Dutch words worldwide, 2010) and who started the website Uitleenwoordenbank

(Loanword database, 2015). There we discover that in the course of history Dutch has loaned 18,242 words to 138 other languages: the total amounts to 48,446 words on loan from Dutch in foreign languages.

An invention such as ‘polder’ can undoubtedly be counted among the top contributions of Dutch to the international vocabulary

The loanword database includes 89 words that have been loaned directly or indirectly to more than twenty languages and have therefore had an international breakthrough. Shipping and hydraulic engineering terms represent more than five percent of the loanwords, a percentage that is higher than in an average Dutch word database. This field is therefore a culture-specific example of how the prominent position and innovative insights of the Low Countries in ship construction and water management have contributed to the fact that to name the new and imported phenomena many other languages often adopt the associated vocabulary unchanged. Loanwords as translation strategy.

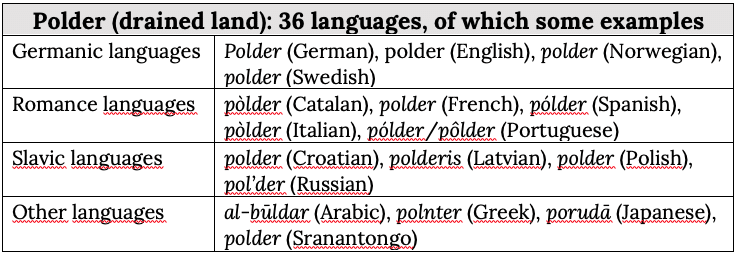

An invention such as ‘polder’, which dates from the late Middle Ages, can undoubtedly be counted among the top contributions of Dutch to the international vocabulary. The inhabitants of the Low Countries were the first in the world to reclaim land from the sea. As a result, the word ‘polder’ has been adopted in many languages, also outside Europe. This international usage, in 36 languages according to the loanword database, has stood the test of time and is still very much alive.

Table 1. Export of polder (that originated in the twelfth century) to different language families

Resources: Uitleenwoordenbank (Loanword database), Etymologiebank (Etymology database) and Reference dictionaries

Dutch international word lending capacity reached its peak in the Middle Ages and again in the nineteenth century. Since then, the Dutch language has borrowed considerably more than it lends. This does not alter the fact that small-scale contacts are constantly taking place in which the “strangeness” and “untranslatability” of Dutch is put to the test. This is especially true for the professional translator.

Translators and the untranslatable

Translatable or untranslatable… That is the question. Translation practice seems to show that everything is translatable in one way or another, if only because translators cannot afford to leave things out.

Untranslatability is based on two premises that are at odds with what we might call the art of translation. The first is that translation is done word for word and the second is based on the belief that borrowing from other languages falls outside the definition of translation. To start with: translators do not translate words, they translate texts. What counts is the whole. This means that, thanks to context and the interplay between words, apparently untranslatable nuances can be compensated and supplemented, so that the jigsaw puzzle still remains intact, even though different pieces are used and they also fit together in different ways.

To return to where we started: translating is conveying what is strictly speaking untranslatable. How is this done? With an arsenal of translation strategies that can be used to solve potential problems. Borrowing foreign words is one such strategy.

Let’s put it to the test. There are many texts circulating on the internet that mention untranslatable words. As a benchmark, I use the glossary of British psychologist Tim Lomas, who is collecting, for a research project, untranslatable positive words that promote well-being and connectedness. The current version of his glossary has 22 Dutch candidates. In alphabetical order: binnenpretje, borrel, deftig, eigenwijs, engelengeduld, feestvarken, gedogen, gelijkhebberig, gezellig, gunnen, luchtkasteel, mierenneuker, niksen, poldermodel, pretoogjes, lekker, sterkte!, uitbuiken, uitwaaien, uitzieken, vakidioot and weemoed.

Many of those words are repeatedly quoted in other publications, including a recent article in De Standaard newspaper entitled ‘Lost in translation’. It is a colourful collection that presents the translator with various challenges.

For example, the list contains words that clearly fall under the heading of culture- specific elements and are particularly characteristic of the Netherlands or of Dutch in general, for example ‘polder model’ (“consultation model aimed at consensus and harmony”, Van Dale) and uitwaaien (“in the wind, walking outside to get fresh air”, Van Dale). Both terms correspond to a phenomenon that is experienced as non-existent in other languages and “typically Dutch”.

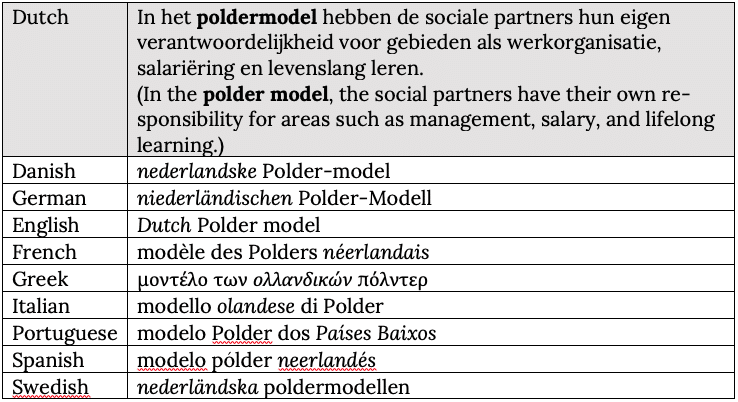

‘Polder model’ belongs to the administrative field and is used, for example, in European Union texts. It has become so entrenched in EU jargon that it has been included as a loanword in the terminology databank of EU institutions. Some EU translations opt for an explanatory description in combination with a loanword between quotation marks, such as: a tradition of Dutch consensual decision making (‘polder model’). However, in the following example, European translators systematically opt for an (un)modified loanword or a loan translation, irrespective of their language, a translation strategy that is combined with additional information about the geographical origin (Dutch/from the Netherlands/of the Dutch). Some translators add quotation marks to indicate that it is a “foreign” and “borrowed” phenomenon. The earlier international integration of the word polder has undoubtedly paved the way for this application of the loanword strategy.

Table 2. Translation of poldermodel in EU texts

Source: EUR-lex

The Dutch uitwaaien (‘A breath of fresh air’) also enjoys a certain international recognition as a cultural phenomenon. In November 2020, for example, numerous newspaper articles appeared in various languages in which it was praised as a remedy against stress and anxiety (undoubtedly triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic and its successive lockdowns). It is also a verb that often appears on multilingual websites promoting Dutch and Flemish tourist destinations. Since it is anything but an attractive loanword due to its complicated pronunciation and spelling, journalists and translators usually opt for a creative description in their own language that is comparable to “getting some fresh air”. Some examples are: Schnuppern Sie die frische Luft (German), Breathe the fresh sea air / Would you like to feel a fresh sea breeze (English) or Te regalamos una bocanada de aire fresco (Spanish).

The Dutch uitwaaien (‘A breath of fresh air’) also enjoys a certain international recognition as a cultural phenomenon

Another obstacle of translation has to do with the fact that many words have different meanings depending on context when those same nuances do not exist in a single word in the target language. Moreover, these meanings are often accompanied by an emotional value that is difficult to put into words, which often differs from person to person. Ask ten Dutch speakers for a definition of deftig, eigenwijs, gunnen, gezellig, (posh, stubborn, being generous, cosy) and you are guaranteed to get different answers. Multilingual dictionaries usually offer a variety of possible equivalents in such cases. It is then up to the translator to interpret the source text and to find a suitable solution.

Gezellig is a classic example that is invariably present in the lists of untranslatable words. The Van Dale dictionary distinguishes three meanings in current language usage: 1) making contact pleasant, 2) a stay that is pleasant, 3) nice, sociable. The multilingual website Mijnwoordenboek (My Dictionary) (Dutch, German, French, English and Spanish) lists just two options, namely “when you are having a great time with others” and “when someone or something makes a very pleasant impression”. For a Romance language such as French, possible equivalents (depending on the context) are, for example, sociable, intime, familial, confortable,

douillet and sympathique; and for a Germanic language such as German there is wohlfühlend, gesellig, umgänglich, unterhaltsam, unterhaltend, freundschaftlich, gemütlich and traut.

Gezellig is a classic example that is invariably present in the lists of untranslatable words

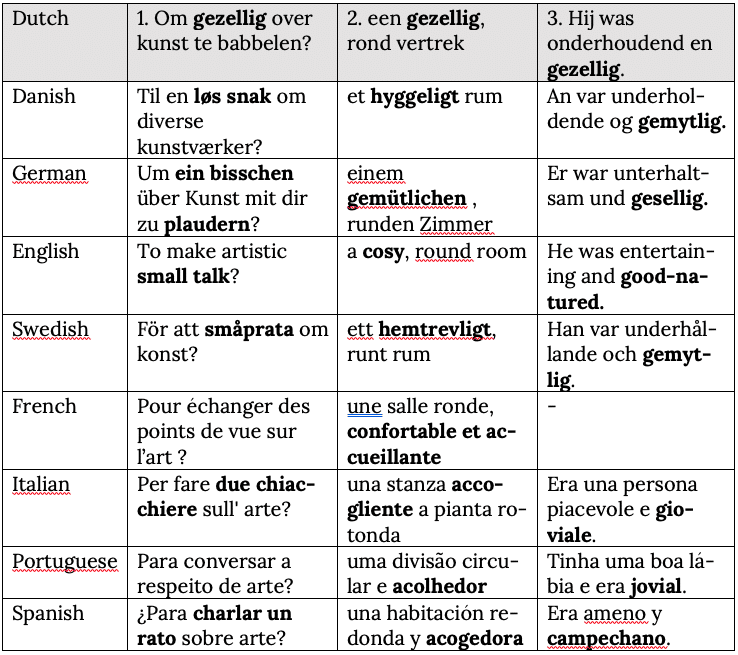

The following example shows that the word gezellig is effectively translated.

Table 3. Variants of gezellig in book translations in different languages

Source: Czech National Corpus

A few observations? Related languages sometimes offer related solutions (French, accueillant; Italian, accogliente; Portuguese, acolhedor; Spanish, acogedor). Translations may depend on the context (Swedish, småprata versus hemtrevligt versus gemytlig). All translations are eventually a personal interpretation. Not all solutions are equally clever and, in some cases, blurring occurs (the French Pour échanger des points de vue sur l’art or the Portuguese para conversar a respeito de arte), but competent translators have plenty of strategies to circumvent untranslatability. In example 1, the Dutch gezellig is largely wrapped up in the verb (plaudern

or charlar) and sometimes a friendly nuance is added (ein bisschen

or un rato). Example 2 evokes homeliness in all languages and in example 3 the complex human quality expressed by the word is interpreted and sensed in its own way by the translators, ranging from German gesellig, which in this context approximates Dutch, to the typically Spanish and equally “untranslatable” campechano.

The last translation difficulty I touch on here is both linguistic and cultural. In the Germanic languages and especially in Dutch there are many compound words that are used in a figurative sense. This is a very productive process for which a different cultural or linguistic solution often has to be devised in other languages. Generally, the following applies here: the greater the relationship between languages and cultures, the more comparable the solutions. For example, some words in the list have an almost literal counterpart in other European languages. For example: castles in the air

(English) or Luftschlösser (German) for luchtkastelen in Dutch. The same goes for engelengeduld. Our common Christian background and Indo-European roots allow the image to be transmitted: either through angels (in the Germanic languages), or through saints (in the Romance languages); either in one word or in several words: angelic patience (English), Engelspatiencia

(German), pazienza di un santo/santa pazienza (Italian) or paciencia de un santo/santa paciencia (Spanish). And even a word such as mierenneuker

or muggenzifter (lit. ‘ant fucker’ and ‘mosquito sifter’) (“someone who makes a dispute over a trivial thing”, Van Dale) can often be translated without losing the metaphor, although the insect sometimes changes its name (in the Spanish chinchoso the ant becomes a louse, in English a nitpicker, and a little bug in the Portuguese bicheiro and coca-bichinhos

and French chercher la petite bête).

Destined to understand one another

What is untranslatable? What is “own”? What is “strange/foreign”? Languages and cultures are melting pots and language contact is happening more than ever. The rise of international affairs and trends is unstoppable and the borrowing of culture-specific words is as old as humanity. It is one of the strategies translators use when they take on the challenge of translating the strictly untranslatable after all.

Ultimately, we are destined to understand each other. Foreign languages and cultures are different and yet they are not. Just as well, otherwise there would be no need for translators and translations.

This article was realised with the support of the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union).