The Battle for Belief. How the Protestant Reformation Shaped the Dutch Republic

American historian Christine Kooi wrote an overview of the first century of the Reformation in the Low Countries. It delves into how politicians and Protestants came together in a revolt against the Catholic Habsburg rulers, thus laying the foundation for the Dutch Republic.

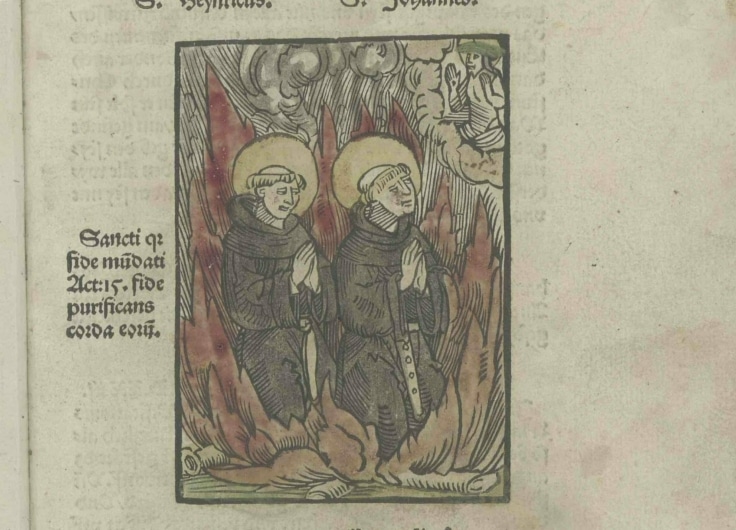

On 1 July 1523, six years after the German monk Martin Luther published his theses against the abuse of indulgences (a redemption payment for the remission of sins) in Wittenberg, the first followers of his unorthodox views were put to death. Two Augustinian monks, Hendrick Vos and Johannes van den Esschen, were burned at the stake as heretics on the Grand Place in Brussels. Like Luther, they challenged the authority of Rome and regarded the Holy Scriptures as the only true source of the Christian faith. But according to the inquisitor’s indictment, they had been guilty of at least sixty-two heterodoxies against Catholic doctrine.

The ecclesiastical authorities had organised a veritable spectacle so that the public execution would serve as a warning to all those who maintained similar ideas. When Luther heard of the execution of his fellow Augustinians Vos and Van den Esschen, he immediately proclaimed them martyrs of the Reformation. He wrote his very first composition, the hymn Ein neues Lied wir heben an, in memory of the two monks.

In Reformation in the Low Countries, 1500-1620, Christine Kooi (1965) describes the fate of the Antwerp martyrs as the first violent confrontation in the Low Countries between the Catholic authority and the rebellious Protestants, who demanded a different church and the freedom to openly profess their new faith.

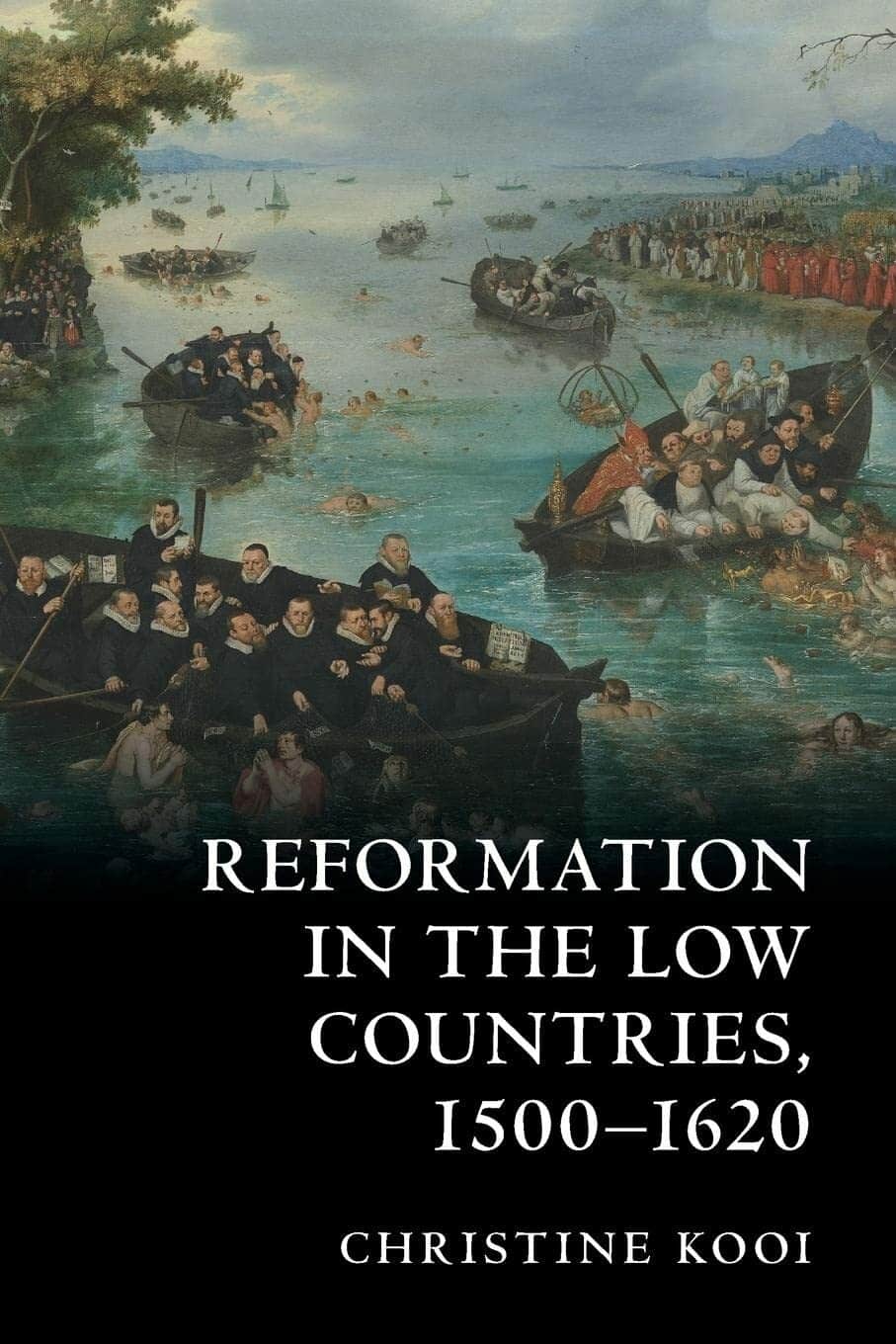

Adriaen Pietersz van der Venne, Fishing for Souls, 1614. The painting is an allegory of the jealousy between the various religious denominations during the Twelve Years Truce (1609-1621) between the Protestant Dutch Republic and Catholic Spain.

Adriaen Pietersz van der Venne, Fishing for Souls, 1614. The painting is an allegory of the jealousy between the various religious denominations during the Twelve Years Truce (1609-1621) between the Protestant Dutch Republic and Catholic Spain.© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

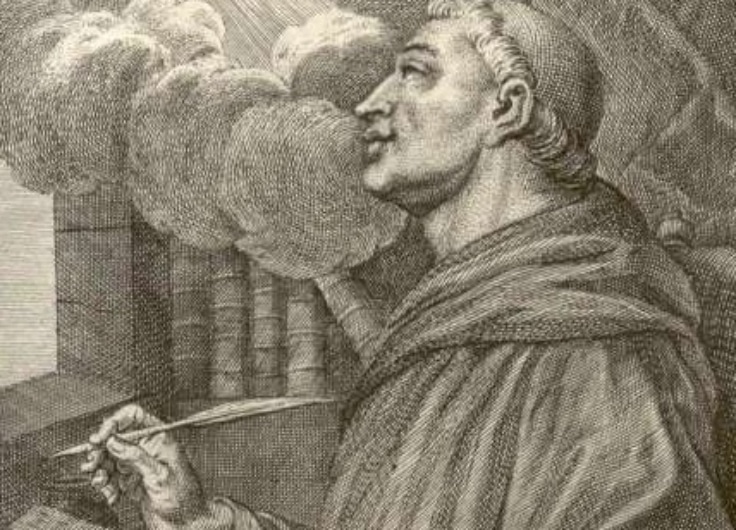

The Reformation, of course, did not occur out of the blue. It came with a long history of dissatisfaction with the Roman Mother Church. In the fourteenth century, the followers of the Modern Devotion in the northern Dutch IJssel Valley were already striving for a simple and devout life in imitation of Christ. Desiderius Erasmus had criticised the complacent Church of Rome with his plea for a new Christian humanism based on in-depth Bible study. But the German monk Martin Luther was the rebel who ultimately lit the fuse with his direct attack on the Vatican church and its many excesses. The fire of his rebellion spread rapidly throughout Europe, also sweeping through the Low Countries.

Kooi, Professor of European History at Louisiana State University, specialises in early modern Dutch religious history. She is the daughter of Dutch parents, but wrote her ambitious study for an English-speaking audience “after a developmental process of thirty years” as an attempt to overcome a historiographical lacuna. She lists numerous older and recent publications, all of which cover only part of the large, complicated jigsaw puzzle, and succeeds in putting all those pieces together into a clear and complete history of religious and political developments in the sixteenth-century Low Countries.

Leaving no stone unturned, Christine Kooi meticulously follows the outbreak of the Protestant conflict that smouldered in the Low Countries

“During the first fifty years of their existence, the various Protestant movements in the Netherlands were hunted, slandered, bombarded and persecuted by a relentless anti-heresy campaign led by the government,” Kooi writes. Between 1523 and 1566, more than 1,300 people were killed because of their deviant faith. But despite the oppression, the Reformation continued growing, not as a large, uniform movement, but along various branches that challenged each other’s true interpretation of the Protestant faith

Leaving no stone unturned, the author meticulously follows the outbreak of the Protestant conflict that smouldered in the Low Countries. She describes the Reformation as “a mosaic of thousands of local stories and circumstances.” Convincingly, she outlines the degrees of chaos and institutionalisation within all movements and sects that emerged in the western parts of the great Habsburg Empire from the 1520s onwards. Ultimately, only the most well-organised remained – the strict religious associations for which Martin Luther and John Calvin had laid the foundations – along with lesser-known reformers such as Huldrych Zwingli, Theodorus Beza and Menno Simons. Zwingli was a kindred spirit of Luther and one of the influential leaders of the Reformation in Switzerland; the French legal scholar and theologian Beza was the student and successor of Calvin; and Menno Simons was the Frisian leader of the Anabaptists and namesake of the Mennonites (which currently has approximately 1.4 million followers worldwide and is the main stream of Anabaptists in North America).

The Dutch Reformation was a grassroots opposition movement with an open and international character that would eventually lead to the unexpected foundation of a completely new state: the Dutch Republic

The Dutch Reformation, a grassroots opposition movement with an open and international character, would eventually lead to the unexpected foundation of a completely new state: the Dutch Republic, or the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. In the late 1560s, religious dissidence and political dissatisfaction with the harsh repression under ruler Philip II resulted in the Dutch Revolt against Habsburg rule. It was a rebellion, a civil war and a religious war all rolled into one. In the Northern Netherlands, the Reformed followers of Calvin became the predominant religion when they entered into a pact with William of Orange and his noble friends, who cleverly linked their struggle with the authoritarian Habsburg regime to the religious discontent.

Christine Kooi creates a solid academic framework that excels as an overview of everything that took place for decades in the cities and regions of the Low Countries. It is an accomplishment that will be greatly appreciated, especially among academics who can continue to expand on her work. Because of the desire for comprehensiveness, Reformation in the Low Countries reads largely like a dry textbook. This is not a disqualification, but rather a word of warning for those who were looking forward to an exciting historiography. War and revolution, heresy and inquisition, iconoclasm and religious strife: the century of the Reformation offers an inexhaustible palette for a painterly, often bloody story. But Kooi chooses to classify all events and developments in a fairly businesslike manner.

Descriptive scenes such as the public trial of the two monks on the Grand Place in Brussels in 1523 are rarely encountered. Only in the conclusion does the American historian resume her detailed description of another major spectacle that took place on 18 October 1618, once again in the Habsburg capital of Brussels. On that day, the relics of the nineteen priests and Franciscan monks from Gorinchem, who were ruthlessly murdered in Den Briel in 1572 by the Protestant Beggars, were transferred “with much pomp and religious passion” to the Franciscan monastery church. Only a block away from the Grand Place, where less than a hundred years earlier the first Protestant martyrs had been burned at the stake.

In the ninety-five years between these two public spectacles, everything had changed in the Low Countries, concludes Christine Kooi. The Habsburg government had lost its northern territories to the Protestant rebels. The heretics were supported by an army and a veritable new state of seven autonomous provinces, officially Reformed but in practice “astonishingly pluralistic.”

The southern regions had ultimately remained loyal to Rome and, in response to Protestantism and following the decisions of the Council of Trent (1545-1563), had undergone their own radical Counter-Reformation. Christine Kooi gives the Catholic reform her full attention too, and rightly so.

Christine Kooi, Reformation in the Low Countries, 1500-1620, Cambridge University Press, 2022, 236 p.

Listen to our interview with Christine Kooi