How a Blue-Collar Team Reached the Top. Feyenoord versus Sparta Rotterdam

Even outside the Low Countries, just about every football fan is familiar with Feyenoord, the popular Rotterdam football club that was a finalist in the Conference League in May 2022. However, initially, it was not Feyenoord but Sparta Rotterdam that was the most successful club on the banks of the Meuse River. The development of both teams is closely linked to the most important social evolution in football shortly after World War I.

The year 1959 was very special for Sparta Rotterdam. After they won the national title, tens of thousands of supporters appeared on the Coolsingel which, taking proportion into account, is more or less the Champs Élysées of Rotterdam. That’s where the players started their tour. For the first time, the mayor received the national champions at the town hall. ‘We in Rotterdam are proud that this well-known Rotterdam club with its illustrious history has achieved this victory,’ he said.

This national title was an exceptional honour for Sparta because, since 1924 another club had always taken the lead in Rotterdam: Feyenoord (named after a neighbourhood south of the New Meuse). Sparta, on the other hand, had achieved its greatest successes before 1924, in the early days when football was still considered an elite sport.

After Sparta Rotterdam won the national title, tens of thousands of supporters celebrated the victory in the city centre.

After Sparta Rotterdam won the national title, tens of thousands of supporters celebrated the victory in the city centre.© Sparta

Elite club

Sparta was founded in 1888 and, in the early days, played on the south side of the Meuse, in a firmly blue-collar, working-class neighbourhood. Yet, the “Spartans” actually came from the highest social backgrounds, which created social tension. ‘At that time, the popular youth in the large port city still had an ingrained hatred against young people from the so-called better classes,’ wrote sports journalist C.J. Groothoff in 1947. ‘Fights, often degenerating into real battles, were the order of the day.’ A year after the club was founded, Sparta received permission to move to the other side of the river, which was ‘a relief’, according to Groothoff.

Sparta had achieved its greatest successes when football was still considered an elite sport

Thus Sparta became, similar to most football clubs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the club of the elite. During the failed socialist revolution of November 1918 in the Netherlands, some Sparta players missed an important game in order to defend their city from the rabble. Piet van der Wolk, for example, was noticed by a reporter from Het Sportblad at the station with a ‘gun on his shoulder and the red, white and blue band around his arm.’

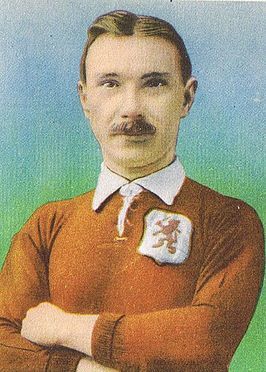

Bok de Korver (1883-1957)

Bok de Korver (1883-1957)© Wikipedia

The best player at that time was Bok de Korver, who also played for the Dutch national team. Under his leadership, Sparta were five-time Dutch champions, and those years were known as the Sparta era. As an international, De Korver played 31 international matches and also won two bronze medals at the Olympics in 1908 and 1912. He was more popular than the royal family, as princess Juliana discovered at a very young age. ‘Mother’, she is said to have remarked to Queen Wilhelmina, in surprise, ‘How often our portraits are in the magazines, much more than those of other people!’ Her mother apparently replied: ‘No, Juliaantje. There is one person whose portrait appears more often than ours: that of Mr De Korver, the football hero from Rotterdam.’

The opening of the Kasteel (Castle) in 1916 confirmed Sparta’s status as the city’s most important club and the first in the Netherlands to have its own stadium. Sparta was undoubtedly the football boss of the Netherlands at that time.

The people's club seizes power

Very different from the ‘elite’ reputation enjoyed by Sparta, Feyenoord, founded in 1908, always had the reputation of being a club of dock workers up until 2015, when Rotterdam experts Jan Oudenaarden and Paul Groenendijk came to a remarkable conclusion: at least half of the very first club members were office workers! Only a year after the club was founded, the first shipyard workers joined the ranks, after which Feyenoord quickly became a people’s club with players and supporters from all walks of life. In 1935, the editor-in-chief of the club magazine wrote: ‘In our club, no doctor, accountant, student, law professor or anyone else is refused. There is not only room for workers here, although the percentage of workers will likely predominate.’ In any case, south Rotterdam’s Feyenoord quickly became the club of the people, the sporting and social counterpart of Sparta.

Feyenoord quickly became the club of the people, the sporting and social counterpart of Sparta

In 1924 Feyenoord won the league title for the first time, so the newspaper Forward, published by the Social Democratic Workers’ Party, organised a celebration in the team’s honour. It may sound strange that a political party took that initiative, but in the early 20th century, the socialists felt particularly attracted to the people’s club from the “wrong” side of the Meuse. The party wrote proudly about the ‘association of young fellows, who have both feet in the middle of Rotterdam’s public life.’ As a result, the club also became particularly popular among the working classes. ‘Therefore her victory is our joy.’

The party had gauged public sentiment well. Soon, the tour from the Delftse Poort station to the then club building on Dordtsestraatweg became a popular festival unlike any Rotterdam had experienced before. ‘There have been many tributes of various kinds in the field of sports in Rotterdam,’ wrote the reporter for Forward, ‘but I have never seen such a tremendous crowd of people as the mass who turned out on Sunday for a celebratory procession of sportsmen.’ The tens of thousands of supporters along the route meant the police had their hands full.

The procession turned out to be a harbinger of the madness that broke out again when Feyenoord won the national title that same year and was given another tour – this time organised by the club itself. The reporter of the Haagsche Courant

could not believe what he saw: ‘As the procession – a long line of cars decorated with red and white flags and wreaths on the hoods – made its triumphal entry on Rotterdam’s boulevard, not a single policeman was visible. The thousands of enthusiasts were free to clamber up onto the footboards and fenders and hang from the hoods of the cars, making progress difficult.’

Photo from the match Sparta against Feyenoord 3-0 in 1961

Photo from the match Sparta against Feyenoord 3-0 in 1961© National Archives / Eric Koch / ANEFO

That 1924 national title left a deep mark on Rotterdam society, because the Feyenoord folk club effectively ended the rule of the elite club. This urban football revolution symbolized the general turnaround of Dutch football at the time, which enjoyed enormous popularity among the men mobilised during the First World War. Because the Netherlands did not participate in the fighting, the army leadership feared that boredom would set-in and radicalised soldiers would revolt. To prevent this, football matches were organised in the army even before the vast majority of participants had made their first acquaintance with the sport. After the war, returning soldiers, especially those in the lower social classes, established their own clubs here and there. As a result, and in a relatively short period of time, football changed from an elitist occupation to a sport for the entire population and also penetrated the farthest corners of the country. Sparta was the pre-revolution club, Feyenoord was the post-revolution club.

The best of Europe

It was only in 1959 that Sparta managed to win the national title. In the following decade, Feyenoord restored Rotterdam’s order once and for all, with their win at the European Cup 1 (the predecessor of the Champions League) in 1970 as the absolute highlight.

A year earlier, Ajax had been the first ever Dutch club to play in the final of the European Cup 1, but the team from Amsterdam lost to AC Milan. Feyenoord is, therefore, anchored in the Dutch collective memory as the first Dutch football club to win the most important football prize in the world for club teams after beating the Scottish Celtic FC.

The party that followed on the Coolsingel celebrated the fact that the Netherlands had become a leading football country, and Rotterdam the leading city. More than a hundred thousand people – there is even talk of double the number – came out to cheer the Feyenoord players. A year earlier, after the team had won the national title, there were also cheering supporters on the same Coolsingel, but only a few hundred, and mainly from the south side of the Meuse.

This lightning-fast development from a few hundred supporters to 100,000 – 200,000 is symptomatic of the change that had occurred in Rotterdam in such a short time, even in the actual relationship between Feyenoord and Sparta. In 1969, national champion Feyenoord still celebrated its status as the best football club in Rotterdam on the Coolsingel. Exactly one year later, the Feyenoord players were not only the heroes of Rotterdam, but of the Netherlands as a whole.

7 May 1970 in Rotterdam. The day after Feyenoord won the European Cup 1 (the predecessor of the Champions League).

7 May 1970 in Rotterdam. The day after Feyenoord won the European Cup 1 (the predecessor of the Champions League).© National Archives / Robert Mieremet / ANEFO

Amsterdam

When it comes to football, a parallel can be drawn between Rotterdam and Amsterdam. Until the First World War, Ajax, a club with a strong neighbourhood affiliation in the east of Amsterdam, was just one of the many football teams in that city. In 1918 Ajax won its first national title, which was celebrated exuberantly. Similar to what would happen a few years later in Rotterdam with Feyenoord’s first national title, the Amsterdam authorities were taken completely by surprise by the folk festival.

After 1918, only De Volewijckers and DWS would manage to win national titles as Amsterdam-based clubs, in 1944 and 1964, respectively. That, of course, did not have much of an effect on the position of Ajax as the most important representative of Amsterdam; similar to the way Sparta has not been more successful in fundamentally undermining Feyenoord’s position.

Feyenoord became the iconic club of Rotterdam and Ajax that of Amsterdam – laying the foundation for the most intense sporting rivalry in Dutch sport. That rivalry became even more intense when both Ajax and Feyenoord made their international breakthroughs in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The matches between Ajax and Feyenoord are now known as The Classic. These are the most loaded matches in Dutch football and winning or losing is a matter that engages and inflames fans far beyond the cities’ limits.

Ajax against Feijenoord 1-2 (cup competition). Johan Cruijff in duel with Laseroms (left) in 1969

Ajax against Feijenoord 1-2 (cup competition). Johan Cruijff in duel with Laseroms (left) in 1969© National Archives / Jac. de Nijs / ANEFO