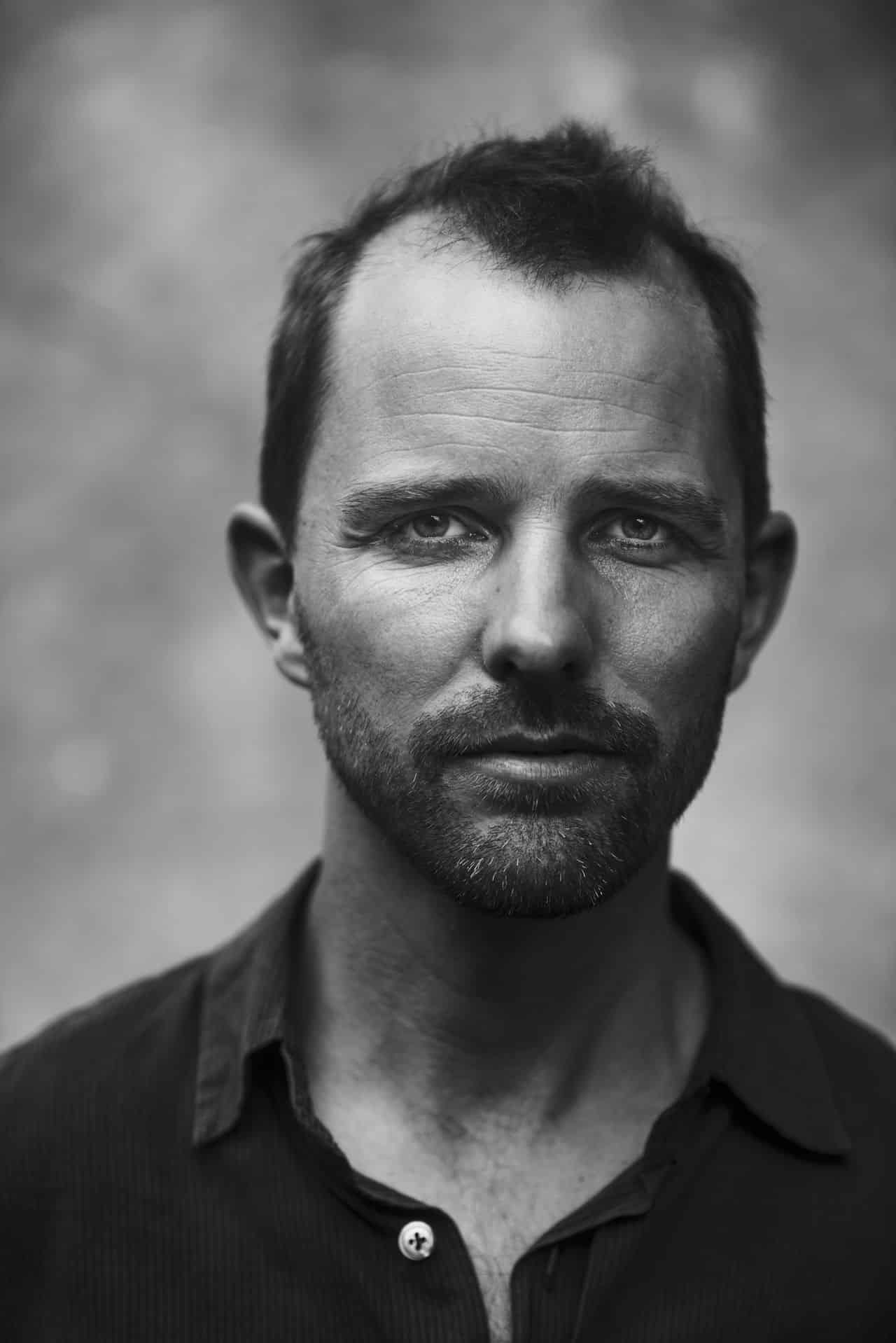

The Beautiful Imperfection of Designer Maarten Baas

He sets fire to furniture, makes seats grow and locks people in clocks to manipulate time. The work of Dutch designer/artist Maarten Baas continues to surprise. His creations are in major museum collections and in private collections of the rich and famous. Welcome to the world of the Tim Burton of Dutch design.

Maarten Baas

Maarten BaasLeading American director Tim Burton features the most grotesque figures in his universe of animated films, which include such visual jewels as The Nightmare Before Christmas, James and The Giant Peach and the utterly crazy Mars Attacks. His gawky characters with their extra-long limbs make a freakish, untidy impression. Indeed, the creatures that appear in many of Burton’s productions look like they have been created from an assemblage of recycled parts. It is obvious that he spent only a few seconds designing them. Their beauty is in their imperfection. Likewise, the nonchalant-looking creations by the Dutch designer and artist Maarten Baas (b. 1978, Arnsberg) would certainly not seem out of place in Tim Burton’s world of spontaneous absurdity. But, in our reality they are, to put it mildly, unexpected figures.

Fire!

Maarten Baas is one of the most striking standard-bearers of the Dutch Design movement. The term refers to a design aesthetic whereby a diverse group of Dutch designers with a sense of humour works to produce results that look minimalist, experimental, innovative and often unconventional. The rise of Dutch Design, which can be situated somewhere in the early 90s, is attributed to the access these designers got to modern, good-quality design courses at places like the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam and the Designacademie in Eindhoven.

Burned Zig Zag chair of Rietveld, from the Smoke series, 2004

Burned Zig Zag chair of Rietveld, from the Smoke series, 2004© Maarten Baas

A former student at the Designacademie, Maarten Baas attracted immediate attention, in 2002, with his final project Smoke, a series of furniture and appliances he had worked on with a gas burner. Chairs, cupboards, pianos and even the red-blue Rietveld chair, the Dutch design icon, were set on fire and burned in a highly controlled way until the form had burned away but the construction remained intact. The charred result was covered with a protective layer of resin and satin gloss, upholstered with new fabric, and could then be used for its original purpose again. With this first professional statement, Maarten Baas immediately indicated what he thought the essence of design should be, namely the achievement of beauty by balancing on the cutting edge of perfection and imperfection.

Spotlight on himself

Furniture Dining Yellow, from the Treasure series, 2005

Furniture Dining Yellow, from the Treasure series, 2005© Maarten Baas

The objects from Baas’s 2005 series Treasure seem to be fabricated in more or less the same way as Tim Burton’s figures, improvised and stuck together with bits of tape, wire and staples. With this second collection, from 2005, Maarten Baas puts great emphasis on the importance of improvisation and spontaneity in his vision of design. It looks as if he nailed bits of recycled MDF wood together purely randomly, regardless of whether they were too long or too short. He did this until he achieved a form that began to look, from afar, like a chair or a table. The whole thing was sprayed in a single colour to achieve some sort of cohesion. At first glance everything seems to indicate that this nonchalant designer is just messing about. But nothing could be further from the truth. Every single object, which Treasure comprises, is unique proof of the way in which one can seek to achieve beauty with imagination and imperfection, and how one can very deliberately give form to intuition.

As he continues to develop his oeuvre, we can see that Maarten Baas increasingly spotlights himself as a creative individual. In his 2006 series Clay, he makes a series of unique furniture and utensils by hand, without using preparatory sketches or templates. In all of the naive-looking results the designer’s hand is not only visible but even tangible.

Clay furniture, from the Clay series, 2006

Clay furniture, from the Clay series, 2006© Maarten Baas

This is the sort of work with which Maarten Baas has established his international reputation as an independent designer. He does not take commissions from others, the starting point for his work is always his own creative enquiry. His independent position also ensures that you can find almost nothing by him that has been reproduced in series. He deliberately stays well away from that sort of industrial approach in protest against the superficiality of a lot of design that is produced in that way. In his interviews he speaks critically about the role of designers in society and the relationship between marketing and design.

Seat, from the Carapace series, 2016

Seat, from the Carapace series, 2016© Maarten Baas

Since the start of his career, Baas has resolutely chosen to make work that is situated on the border between art and design. Many of his objects are unique and rather pricey. He does not believe in the principle that design should be democratic. He is very pragmatic about it in the entertaining FAQ section of his website. “Democracy works well as a method with which to shore up a political system, but it is a less usual concept in the creative process. I prefer to ensure that sales can support the production of new works. After all, everyone can enjoy them free of charge on the internet or in magazines.”

Locked in a large clock

Grandfather clock, from the Real Time series, 2009

Grandfather clock, from the Real Time series, 2009© Maarten Baas

Fortunately, there are other ways of enjoying Maarten Baas’s work. It is certainly worth the effort of going to terminal 2 of Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam, for example. There you will find the much talked about video work Schiphol Clock, from 2016. This installation, which is more than three metres high, consists of an archetypal clock the size of a man. It can be accessed through a little door on the inside that is reached with a ladder. Inside the clock, behind the blurry glass clockface, viewers can see the projected silhouette of a person painting the hands every minute and then wiping them away again. It really does look as if there is someone shut up in the clock, constantly creating time. By literally cleaning away every minute and drawing a new one Maarten Baas has created an exceptionally poetic ode to transience.

Like Tim Burton, Maarten Baas succeeds in his unique way in generating beauty by combining imperfection with transience. With spontaneity and a generous portion of humour he achieves objects and installations that leave viewers anything but unmoved. Here is a tip for real fans without the necessary financial resources: you can download an analogue clock from the Apple App Store. It is a work of art based on the same concept as the artwork in Schiphol, and it costs a mere €1.09. You can’t get more democratic than that.