The Birth of Damn Homo Sapiens: ‘We, Hominids’ by Frank Westerman

Who are we? Where do we come from? What makes us human?

In We, Hominids, the award-winning Dutch non-fiction writer Frank Westerman searches for answers to anthropology’s most fundamental questions. With an ancient skull as his starting point, he travels the world, in search of the first human being: the missing link between humans and apes. With this Dutch bestseller, recently translated into English, Westerman once again proves himself a masterful storyteller.

Reportage is the queen of journalistic genres. It is the basic form: someone asks himself a question, does some background reading, sets off, looks around, talks to people, describes them, notes down what they say and what they don’t say, becomes personally involved, does even more background reading, makes connections. It’s certainly time-consuming. But you end up with a convincing story, based on genuine reality.

Frank Westerman

Frank Westerman© Lionne Hietberg

In the best case such a story has everything – it can also go horribly wrong. It is authentic, topical, alive, exciting, moving, or it provokes rage. It takes facts, for instance, from science or historiography and narrative techniques from literature. The best reportages are personal rather than ego-fuelled, show vision but let the readers draw their own conclusions.

It is a shame that most paper newspapers and magazines have little space for long, paper-devouring reportages. The online longread offers a solution, but the time investment remains considerable. You can also take all the space you need and make a book of it. The best reportage writers began as reporters, but now write mainly books.

In the work of Frank Westerman, one of the greatest non-fiction writers in the Dutch language area, the footprint of the reporter can still be recognised – that makes it so good. At the same time Westerman, right from his debut in 1999 with De graanrepubliek (The Republic of Grain), up to and including his tenth book, published at the end of 2018, Wij, de mens (We, Hominids), is a thoroughbred writer, also relying on his style and an ingenious narrative line.

Westerman could easily write a good novel, but he doesn’t want to. He opts for reportage, he writes in We, Hominids, because he “can’t compete with reality in fantasy”. He constantly comes across “true stories that make such an unbelievable impression, that, if immersed in fiction, they would lose their last membrane of credibility”.

Too true to be good

This reasoning is diametrically opposed to that of Gerard Reve, who often found reality incredible, too good to be true. Which is why he chose fiction. Westerman turns this on its head: “Many things are too true to be good.” Reve, an autodidact and self-declared Catholic, preferred to believe in his own truth and symbolic language; for Westerman, raised as a Protestant according to the letter of the Bible and trained as a scientist in tropical agriculture, facts are sacred.

Westerman followed in the footsteps of Reve as guest writer at the University of Leiden, a post which Reve held as the first incumbent in 1985. Thirty-two years later Westerman became the first non-fiction writer to occupy the position. With his students, he put his own work “on the dissecting table” and taught them the basic principles of reportage – that is: Westerman reportage. The most important point in his view is that a reportage issues from amazement: “Whatever you report, in your mind you can always preface it with a ‘Just listen to this!’” An infectious piece of advice. That passion makes even his shorter reportages such a joy to read. A section of these, about the Netherlands, were collected in 2017 in Het land van de ja-knikkers. Verhalen uit de polder (The Land of the Nodding Pumps. Stories from the Polder).

Another good tip is to include the search and the course of the thinking and writing process in the story. It is not necessary, but Westerman always does it in his books and that is precisely what prevents his work from ever becoming kitschy; there are no “found”, all too beautiful stories. They are right under our noses. Setbacks en route make the adventure even more beautiful: “They are like enriched uranium, and have a higher dramatic atomic weight than triumphs.”

The subject of the book that he wanted to write “together” with the students that was to become We, Hominids, was conceived by Westerman himself. He would go in search of the origin of human beings, in the birth room of humanity. In what way does homo sapiens differ from the animal, the ape from which it is descended? What made human beings a species with emotions, ideals and memories, but also with the tendency to destroy their own kind and their own planet? Where did the transition take place from man-ape to ape-man, walking upright?

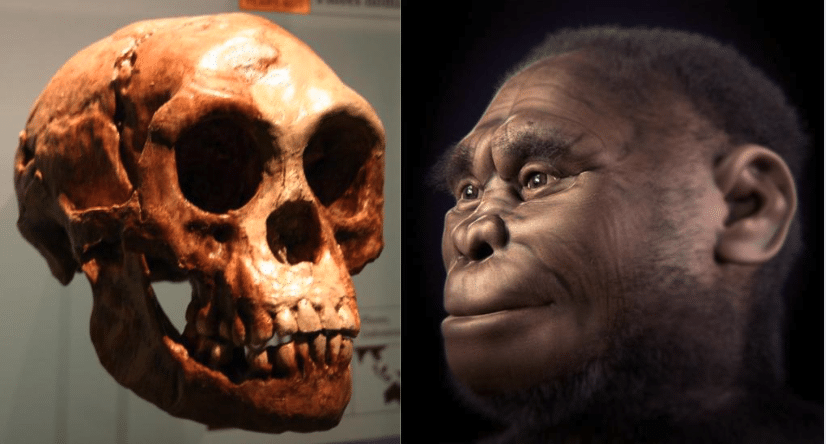

Liang Bua, the cave on the Indonesian island of Flores where Flores Man was discovered.

Liang Bua, the cave on the Indonesian island of Flores where Flores Man was discovered.Westerman’s starting point is the discovery in 2003 of the remains of “Flores Man” by the Australian Mike Morwood in a cave, Liang Bua on the Indonesian island of Flores. This human, who lived some 70,000 years ago, was small, just over a metre tall, had a small skull, but walked upright. Was this creature the missing link between ape and human? In Liang Bua the remains had previously been discovered by the Dutch priest Theodoor Verhoeven, of dwarf elephants and rats as big as pigs. Proportions in that cave seem to have been lost. As if a magician had been at work.

Westerman divides the research work among his students. They must particularly seek information about paleo-anthropologists who have concerned themselves with “primal man”, while he himself goes on reflecting on homo sapiens and the minimal difference with the great consequences.

The skull and reconstructed face of Flores Man.

The skull and reconstructed face of Flores Man.The aim of the research is not completely clear, but that does not seem to be a problem. In earlier books too Westerman did not know precisely where he would wind up and that led to fascinating peregrinations. In El Negro en ik

(The Negro and Me, 2004) the starting point is the image of a stuffed African, seen by Westerman in a Spanish museum at the age of nineteen. It takes him on a search into Western thought about race, identity, colonialism and slavery, and makes him think differently about his own training as a development worker.

In Dier, bovendier (Animal, Super Animal, 2010) a horse is the starting point, a horse of the noble Lippizaner breed, popular with kings and emperors. The horse sweeps the writer and his readers along through the history of twentieth-century Europe. Via the animal Westerman wants to gain “an insight into the peculiarities of our own species”.

The most interesting pages in the book are about human beings, not about “humankind”

This time that is ultimately also Westerman’s intention, but now the question – “what determines the human species?” – involves casting the net all too widely. Many facts are disputable. The paleo-anthropologists and archaeologists and inspired amateurs who over the course of time have studied “hominids” are often in disagreement with each other and argue passionately about the honour of a unique find and the worldwide fame that attaches to it. The stories about the jealous, ambitious macho researchers constitute the most interesting pages in the book; they are about human beings, not about “humankind”.

The present-day serious scientists that Westerman speaks to are, surprisingly enough, scarcely interested in what so fascinates him: the crucial difference between humans and animals. For these researchers humans are simply a species of animal; they are searching rather for similarities. In his previous books Westerman, as a writer and journalist, could research for himself, by digging into history, by observing and comparing, now he is dependent on specialists. He does not plant a spade in the ground to dig up skulls. Now he is the prejudiced amateur. That makes his position uncomfortable – “You already know the answer”, a researcher snaps at him, “so why do you ask?”

The British edition of 'We, Hominids'

The British edition of 'We, Hominids'I must confess: We, Hominids is the first book of Westerman’s that I did not read from cover to cover with breathless enthusiasm. As before, I was struck by the supple way in which he associates and narrates. But I kept asking myself: what was the question again? Westerman really did not convince me. Perhaps that is because the finds of all those hominids, of Lucy, Krijn, Flores Man, Java Man and the girl from Taung interested me only moderately – that is definitely my fault. A portion of Westerman’s students also dropped out. I recognised myself – with some sense of shame – in the 55-year-old art historian Els, who said: “If you start talking about human apes, I think: yeah, yeah.”

Not an organic whole

However, it is not just that. The subjects of previous Westerman books – Russian engineers, the agriculture of Groningen, Mount Ararat – did not appeal to me in advance, yet he carried me along with him. In We, Hominids he piles on lots of stories: the life stories of the earlier researchers (sometimes tragic, as with the abusive past of Father Verhoeven), the expansive interviews. Scientific details about graves, caves and bones, journey to Flores with his daughter. In addition, there are the findings of his students and the course of the lectures. This abundance does not come together organically, as we are used to with Westerman.

At the end of the book, he no longer seems to believe so strongly in his mission. When they reach the Liang Bua cave on Flores, where new excavations are taking place, the holes are just being filled in again. Westerman’s contact is at a conference in Australia. What kind of careless planning is this?

The Australian edition of 'We, Hominids'

The Australian edition of 'We, Hominids'During the trip on Flores other human remains attract his attention, of more recent date: the island turns out to be strewn with mass graves. In Indonesia, in 1965, during a manhunt for supposed Communists, a quarter of a million inhabitants were put to the sword. Many people on Flores suffered that fate; the Catholic priests, including the Dutch, looked the other way. For Westerman that fact puts the excitement over ancient human skulls into perspective.

Frank Westerman is at his best when he shows us what human beings are capable of, good and bad, when they are filled with ideals, beliefs or ambition. His previous book, Een woord een woord

(A Word a Word, 2017), is a model of a perfect reportage, from which students can learn the art effectively. In it ,he investigates what “the word” can do in the face of terror. As a child, he experienced at close quarters the Moluccan train hijackings in Drenthe, in 1974 and 1977. The reconstruction of those hijackings – the second of which ended in a bloodbath, on the orders of the Netherlands state – moves smoothly into an impressive discussion of the motives of ideologically driven terrorists. That damn homo sapiens is Westerman’s subject. For that, you look at his deeds, not his bones.

Frank Westerman, We, Hominids. An anthropological detective story, Black Inc., Melbourne, 2021, 288 pages

Frank Westerman, We, Hominids. An anthropological detective story, Head of Zeus/Apollo, London, 2022, 288 pages

(translated from Dutch by Sam Garret)