The Bold and the Bawdy: How Sexual Slang Became Mainstream in Dutch

Sexually charged words are so ubiquitous in the Dutch language that we no longer bat an eye. Over time, there has been a shift from scholarly medical terms and veiled descriptions to explicit expressions. Yet, talking about sex still carries a lingering sense of taboo – one that might be staging a comeback.

In 1970, Rouke Broersma published Recht voor z’n raap. Jargonboek voor hippe en andere vogels, in which he notably delved into lewd language. This was evident in the extensive number of compound words with sex (spelled in Dutch this way back then): sex act, sexblad (sex magazine), sexbonbon (sex bonbon), sexgolf (sex wave), sexhit, sexiotheek (sex library), sexlingerie (sex lingerie), sexpol, sexshop, sextiek, sextruitje (sex shirt), and sexy. He explained sexgolf (sex wave) as ‘the widely apparent increased interest in sexuality’ – his book serves as a clear testament to that phenomenon.

However, things were different for a considerable period. The growing interest in sex initially emerged within scientific circles. Seksuologie (sexology) arose as a new discipline in the early twentieth century, prominently represented in Germany (Freud, Bloch) and the United States (Kinsey). Sexologists primarily focused on medical aspects. They borrowed terms for genitalia from the distant medical Latin: referring to genitaliën (genitals), penis (penis), testikels (testicles), fallus (phallus), erectie (erection), vagina (vagina), and clitoris (clitoris). Latin words for the act itself such as copuleren (to copulate), coïtus (coitus), and orgasme (orgasm), or more specific words like masturberen (to masturbate) or onaneren (to masturbate) were used to describe sexual acts. Additionally, they used morally guided, euphemistic descriptions such as geslachtsdeel (genitalia) and schaamdeel (private parts), roede (rod), schaamlid (genital member), schede (shaft), kittelaar (clitoris), and vague, ambiguous verbs like klaarkomen (to climax) and aftrekken (to jerk off).

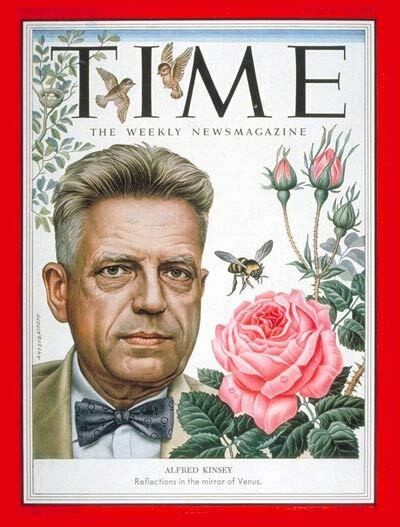

Alfred Kinsey on the cover of TIME in 1953

Alfred Kinsey on the cover of TIME in 1953But in 1948 and 1953, Alfred Kinsey published two explosive reports on the sexual behaviour of men and women, respectively, based on a population survey, not solely from a medical perspective. Following this, sexologists increasingly emerged in the public sphere, offering advice and education to the general public, soon appearing on television as well.

Kinsey’s work was characterized as a sex-bom (sex bomb) in a Dutch newspaper in 1953. This term was subsequently applied to film stars like Marilyn Monroe. Newspapers had been highlighting the sex appeal of these actresses since as early as 1929. Thanks to these sexbommen (sex bombs) and their allure, the English term sex for ‘(depictions of) sexual intercourse’ gained prevalence in Dutch around 1950. On 25 March 1950, a journalist described a movie theater filled with ‘individuals captivated by an overwhelming stream of sexual content.’ Despite the journalist’s disapproval, adopting sex as an English loanword offered a welcomed substitute for a topic that caused discomfort among well-mannered individuals when openly discussed. Additionally, there was no appropriate Dutch term suitable for refined conversation.

Thanks to sex bombs and their allure, the English term sex for ‘(depictions of) sexual intercourse’ gained prevalence in Dutch around 1950

The term sex as used today, didn’t immediately gain widespread use. As late as 1951, a sex-school (sex school) was established in Barneveld ‘where students were taught the challenging skill of determining the gender of one-day-old chicks.’ This event made headlines in all newspapers and inspired Annie M.G. Schmidt to write a playful and ambiguous column in the Dutch newspaper Het Parool: ‘[I] was so convinced that there would be no sex happening at the Barneveld sex school on the day I visited. Who sexes

anyway, or rather, who sketches? Imagine my surprise when I noticed that there was indeed sex happening at the sex school. But this all needs an explanation: the sexing is done with chicks, referring to determining who are the roosters and who are the hens.’

Club Climax

From the mid-1960s onward, there was a noticeable rise in references to sex or seks within newspapers, directly linked to the sweeping seksuele revolutie (sexual revolution) that swept through the Low Countries. The Dolle Mina’s, an integral part of the second wave of feminism, advocated for gender equality. This movement gained momentum with the introduction of the pil (pill) or anticonceptiepil (contraceptive pill) in 1964, along with other contraceptives like the spiraaltje (coil), the prikpil (contraceptive injection) and the dalkonschildje (diaphragm). These advancements empowered women to take control over the risk of pregnancy, reducing reliance on the mannencondoom (male condom), an English loanword since 1847, commonly known as kapotje (rubber)

or referred to in the refined medical circles as preservatief (prophylactic).

Sexuality and marriage began to disassociate, and the Provo and hippie movements advocated for vrije liefde (free love), partnerruil (partner exchange), and buitenechtelijke sex (extramarital relations). This was sometimes even institutionalized: newspapers in 1969 expressed outrage when the British intercontinental airline BOAC contemplated offering rendezvous trips to American travellers bound for swinging London, described as ‘the capital of the permissive society (where anything goes).’ They proposed offering encounters with ‘individuals of the opposite sex’ if passengers completed questionnaires with items such as: ‘Are you sexy, do you believe in love at first sight (very important for a trip that lasted only two weeks), is sex important to you, do you believe in extramarital relations, etc., etc.’

The sexual revolution penetrated mainstream society through newspaper advertisements of clubs like Club Eros and Club Venus

The sexual revolution penetrated mainstream society around 1973, evident through numerous newspaper advertisements of clubs that barely concealed their intentions with names like Club Eros, Club Venus, Club Aphrodite, Club Climax, Club Paris, Play-time Club, or Helio Porno Club. These establishments offered services such as ‘porno-erotic show program – nude acts – new sexual films in colour – nude services in the venue – strip entertainment at the bar,’ or ‘porn games on stage performed by a man and a woman: foreplay and positions, realistic and explicit!’

The era of free love and sexual liberation dismantled the taboo around sexual terms. People openly began using descriptive language. Latin medical terms like vagina and penis, as well as outdated literary words like schede (shaft) and roede (rod) were replaced by once-considered vulgar terms, such as kut (vagina), lul (cock), piemel (penis), piel (dick), and kloot (ball). These existing words took on new sexual contexts, like doos (box), eikel (penis glans), paal (pole), and pik/houweel (penis). While the meaning had been known for a while, they were previously used discreetly in small circles.

The era of free love and sexual liberation dismantled the taboo around sexual terms

The daad (sexual act itself) was openly referred to as naaien (to screw), neuken (to fuck), wippen (to shag), kezen (to fornicate), or vozen (to fumble). These words had long existed but were once considered quite uncouth. New synonyms emerged, such as vrijen (making love), rampetampen (to have sex), pijpen (to give head), beffen (to go down on someone),

and standje negenzestig (sixty-nine position).

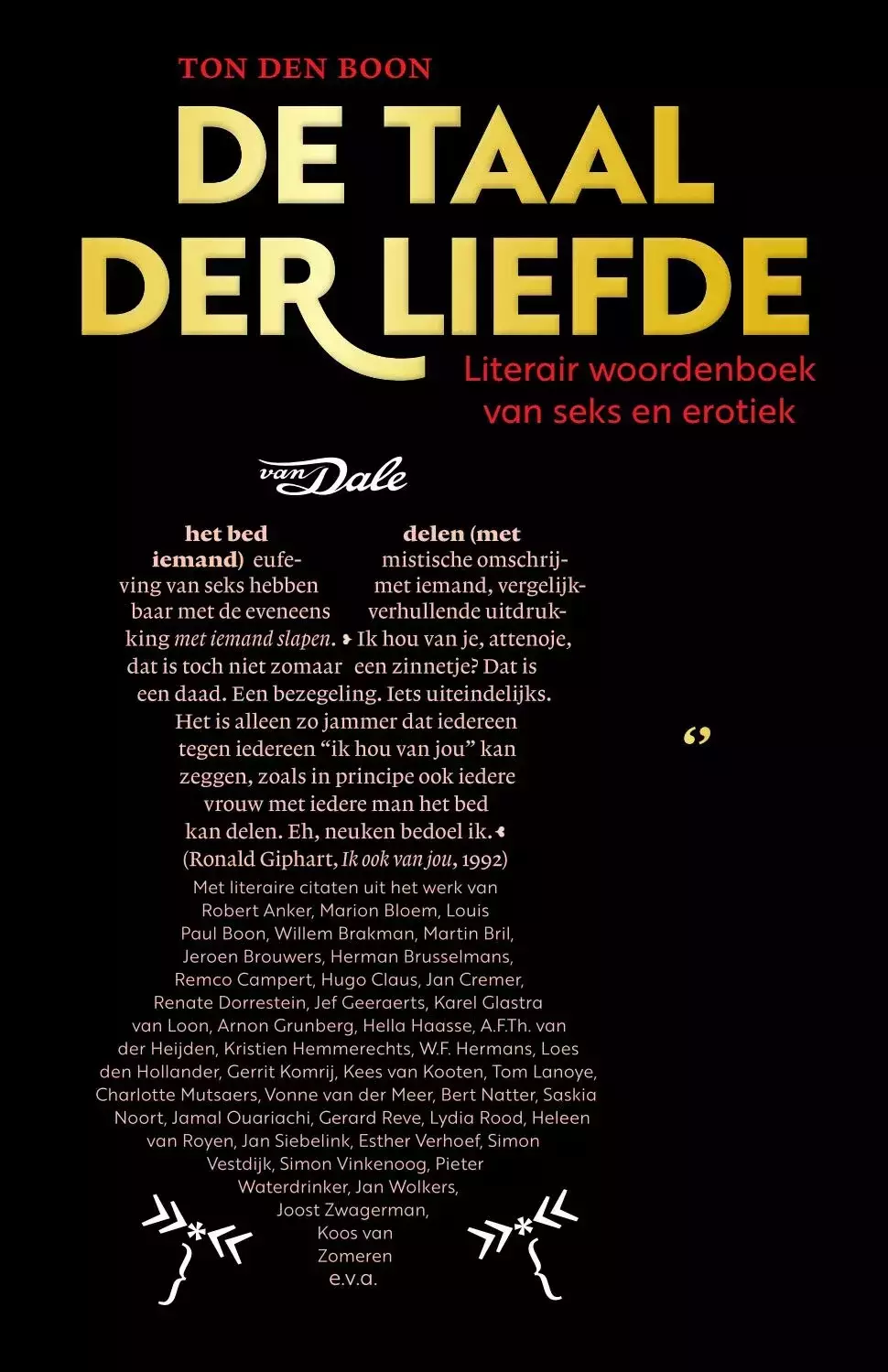

These words, more or less established and commonly used, have now found their place in dictionaries. Ton den Boon vividly describes this evolution in De taal der liefde. Literair woordenboek van seks en erotiek (2017): ‘Almost any elongated object – from a banana to a liquorice stick, from black pudding to a meat lolly, from a chisel to a whip, and from a firehose to a seed stalk – is occasionally used metaphorically to refer to male genitalia. Similarly, various terms alluding to a hole – such as drilling hole or play area – are metaphorically used to refer to female genitalia.’

The Dickheads

The exposure of the general public to the new sexual lexicon happened through television, literature, and cinema. Remco Campert’s 1962 poem ‘Niet te geloven’ included the iconic line ‘Alles zoop en naaide’ (Everyone was drinking and fucking). This line sparked a broadcast dispute in 1964: the AVRO censored the poem from television broadcast twice, deeming it ‘unsuitable for mass consumption.’ Equally controversial was the first use of the word neuken (to have sex) on the Dutch stage in 1964, when actress Sylvia de Leur recited from the book Ik, Jan Cremer.

Almost any elongated object is used metaphorically to refer to male genitalia. Similarly, various terms alluding to a hole are metaphorically used to refer to female genitalia

The cabaret scene facilitated the acceptance of the daring vocabulary. In 1977, the duo Van Kooten and De Bie introduced terms like bonken (to bang), van wippenstein gaan (to have sex), pruimen op sap zetten (to engage in sexual activities), geilneef (lecher) and in 1980, dameswensen (ladies’ desires). During the 1990s, the absurdist series De Lullo’s (The Dickheads) by Kees Prins, Michiel Romeyn, and Herman Koch, satirized fraternity guys by echoing the often-asked question ‘Hey dickhead, have you fucked yet?’.

Out of the closet

Thanks to the guy liberation movement in the 1960s, homosexuals and lesbians began coming out en masse; choosing either to uit de kast komen (a translation of the English to come out of the closet) or, conversely, to remain closeted, described as kastnicht (a translation of closet queen or closet queer).

In his book 'Nader tot U', Gerard Reve described having sex with God in the form of a donkey in 'his secret opening'.

In his book 'Nader tot U', Gerard Reve described having sex with God in the form of a donkey in 'his secret opening'.© Anefo / Joost Evers / Wikimedia Commons

Gerard Reve’s book Nader tot U even led to a lawsuit in 1966. In the book, Reve described having sex with God in the form of a mouse-gray donkey in zijn geheime opening (his secret opening). The ensuing ‘donkey trial,’ popularized the expression geheime opening (secret opening) as slang for a man’s buttocks, similar to herenliefde (gentlemen’s love), or being inclined towards Greek principles (to be gay), about which Reve ironically reported.

In 1988, journalist and writer Arendo Joustra compiled the language of homosexual men in the homo-erotisch woordenboek (homo-erotic dictionary). He focused solely on male language, as he believed that ‘lesbian language’ didn’t exist. However, Hanneke Kunst and Xandra Schutte disproved this belief in 1991 with the book Lesbiaans: Lexicon van de Lesbotaal (Lesbiaans: Lexicon of Lesbian Language). Both dictionaries encompass a wide array of words and expressions, many of which, like aspects of sexuality, have been borrowed from English. These include terms like darkroom, bondage, cockring, cruisen (to be flirtatious), cuntteaser, dijk en dyke

(lesbian), fistfucking, gay, gesbian (mering gay

and lesbian), piercing, queer, spanking, and straight.

Goat fucker

Not everyone welcomed the widespread use of explicit language. As early as 1962, the booklet Nette en onnette woorden (proper and improper words) was published by the Catholic publishing house Paul Brand, featuring a linguistic contribution by the esteemed professor J.A. Huisman. Huisman presented various examples of inappropriate language, including terms like neuken (to fuck), schapenneuker (sheepfucker), naaien (to screw), poten (lesbians), kut (vagina), pruim (vagina), pik (penis), piel (dick), potlood (dick), and lul (penis). He also highlighted swear words such as klootzak (jerk), flicker (faggot), ouwe lul (old dick), ouwehoer (old gossip), and lullig (silly), as well as phrases as ik weet er geen zak van (I don’t know anything about it), lig niet te ouwehoeren (stop messing around), and ‘t is kloten (it sucks). Huisman contextualized the entirety within a historical development and noted: ‘In assessing these ‘forbidden’ words, it’s crucial to recognize their developmental process. Some are on their way to becoming respectable words.’ Many of Huisman’s contemporaries may have read these words with a tinge of embarrassment.

It is uncertain whether they became accepted as proper words, but the sexually suggestive terms certainly became widely used. They took on a new role as both exclamations and prefixes: klote! (shitty), kut! (shit!), klotefilm (shitty movie), and kutsmoes (shitty excuse). Conflicting terms emerged, such as kutvent (jerk) and klotewijf (fucking bitch). Additionally, new compositions were coined, such as mierenneuker (nitpicker), oetlul (dickhead), luldebehanger (asshole), klooien (to mess around), kloten (to mess around), kutten (to fuck with), en opgeilen (to turn on). Terms like fuck, fokking, and motherfucker, borrowed from English, also gained widespread use.

Yet, certain words and contexts continue to be deemed taboo. When the acclaimed director Theo van Gogh referred to Muslims as goat fuckers in 2003, it triggered a massive controversy. Additionally, in 2004, for the first time in the history of professional football, a match was halted because supporters collectively labelled the referee a hoer (whore). This term, along with geitenneuker (goat fucker) and ‘references to genitals, race, religion, or population groups,’ was banned by the Royal Dutch Football Association in 2005. However, despite these measures, further actions were necessary: in 2023, new policies were implemented to address chants of ‘homo, homo’ in football stadiums.’

Willy-mouse

The progression of time has marked a shift from scholarly medical terms and veiled Dutch descriptions to explicit raw-life expressions. However, these explicit terms are unsuitable for sexual education aimed at an increasingly younger audience. The objective is to shield them from society’s seksualisering (sexualization) and pornificatie (pornification), while also raising awareness about the dangers of loverboys, grooming, and sexting. Since the controversial airing of BNN’s program Neuken doe je zo in 2003, much has changed.

Today, many schools and parents grapple with the dilemma of finding appropriate terms to preserve children’s innocence. Online, they share suggestions such as voorbips (front-bum), doos (box), spleetje (slit), foef (fanny), vagijn (vagine), pruimpje (plum), poenie (poon), pielemuis (willy-mouse), plassertje (little wee-wee), pipi (pee-pee), and piemel (penis). Equally cautious is the term Week van de Lentekriebels (Week of Spring Fever), an annual focus on sexual education in elementary schools since 2005. However, in 2023, the theme Wat vind ik fijn? (What do I like?) unexpectedly sparked a huge controversy due to a video in which parents talked with their children about their bodies.

This reflects a return to the taboo atmosphere of a century ago, a time when sexuality was veiled. It’s mirrored in the establishment of intimiteitscoördinatoren (intimacy coordinators)

in the film and theater industry since #MeToo.