‘The Burgundians’, a Sparkling History of the Origins of the Low Countries

In 1919 the Dutch historian Johan Huizinga published his book The Autumn-tide of the Middle Ages, in which he sketches an image of France and The Netherlands in the 14th and 15 centuries. The book has been widely translated and is still read and regarded a staple work. A century later, Bart Van Loo’s The Burgundians, positions itself as its successor.

The readers seem to agree: since the original Dutch version of The Burgundians came out in January 2019 it has dominated the bestseller lists. It seems that Bart Van Loo himself wanted to emulate Huizinga too. His book is no less thick than The Autumn-tide, and much like Huizinga, Van Loo often draws from French literary sources and predominantly pays attention to cultural history.

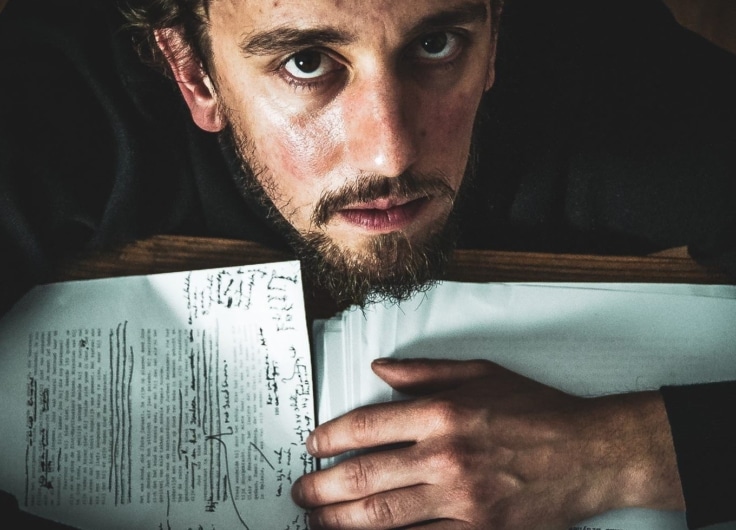

Author Bart Van Loo dressed as a Burgundian ruler

Author Bart Van Loo dressed as a Burgundian rulerBut there are also some important differences between the books. Huizinga upheld an academic register; his sentences meandered across the pages, and with that he contrasted The Passionate Intensity of Life that he detects in the 14th and 15th centuries, with the rationality of the 20th century. Van Loo, on the other hand, writes with a straightforward style and doesn’t shy away from popular language – with him, even dignitaries can turn out to be good eggs, and every now and then sincere curses escape his characters. At such moments, Van Loo’s ‘stand-up’ side – touring the Netherlands and Flanders he pulls crowded halls everywhere – gets in the way of the author.

Although just like Huizinga, Van Loo paints the exuberant characters of his protagonists – the Burgundian dukes, their entourages and the accompanying backdrop – in bold colours, his stories do not evoke alienation but are rather recognisable to contemporary readers. For example, the cunning duke John the Fearless seems to have run away from the set of Game of Thrones. In short, Van Loo does not analyse, he tells a story.

Never bored

That story starts in the fifth century, in the Migration Period, when the Burgundians, one of the many Germanic tribes, crossed the Rhine to eventually settle in eastern Gaul, present-day France. 500 pages and at least a millennium later Van Loo concludes his epic with Emperor Charles V’s lavish funeral in Brussels. In between, a huge number of emperors, kings, dukes, prelates, knights, artists and sometimes ordinary townspeople cross the reader’s path. Van Loo has a catchy anecdote for each of them, and so the reader is never bored.

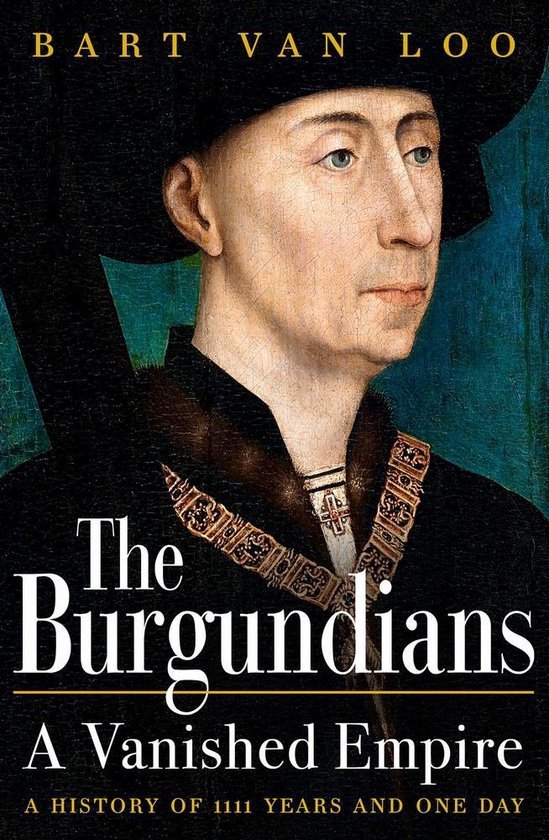

Simon van de Passe, portrait of Philip the Bold

Simon van de Passe, portrait of Philip the Bold© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Even when his trivia scores highly on the se non è vero, è ben trovato scale (don’t let the truth get in the way of a good story), he honestly admits it. For example, I found it particularly amusing how Van Loo traces the etymology of mustard, moutarde in French, to the motto Moult me tarde of the ever-troubled duke Philip the Bold – only to add that he included this particular story as it’s a view that suits his purposes very well.

Love of France

Bart Van Loo is originally a Romance philologist. He understands the subtleties of the French language and his love for France explodes from the pages. Previous to The Burgundians he published a biography of Napoleon and a literary travel guide for France. Van Loo wants to lure his readers away to France. If they admire the pleurants (mourners) carrying the tomb of the aforementioned Philip the Bold in Dijon’s Musée des Beaux-Arts, with his book in their hands, he claims to have accomplished his mission.

Van Loo arouses interest in the past among thousands of readers, spectators and listeners in an inimitable way

It is to Van Loo’s great credit that he succeeds in this. He arouses interest in the past among thousands of readers, spectators and listeners in an inimitable way (a series that the Flemish radio Klara made of the book can be downloaded as a podcast from the Klara website, as well as Van Loo’s own website). An endless string of associations, one more daring than the other, and many cliffhangers help him to do this. With this Van Loo switches effortlessly between time and space: whether it’s from the 14th century duke Philip the Bold, to the nineteenth-century writer, revolutionary and politician Alphonse de Lamartine, or from Beaune to Bruges, for Van Loo these are just small steps.

And with this I immediately highlight one of the problems in this book. Patriarchs of the Low Countries is the subtitle of the original Dutch version of The Burgundians, and with it Van Loo refers to the four dukes – Philip the Bold, John the Fearless, Philip the Good and Charles the Bold – who ruled Burgundy and many other regions in the century between 1363 and 1477. In the first year, King John the Good gifted the duchy to his youngest son as a thank you for the fearless manner in which he had assisted him in the Battle of Poitiers (1356), which ended unfortunately for the French. In January of 1477, Charles the Bold the last duke fell, after a series of military defeats at the gates of Nancy. Immediately his arch enemy, the French King Louis XI, seized all areas he could lay his hands on, including Burgundy.

Van Loo gives the book great pace and the reader must, as it were, constantly gasp for breath

Van Loo’s perspective is thus essentially French. It fits seamlessly into the narrative that was developed by Jules Michelet in the first half of the nineteenth century, still taught in French schools today. But the Burgundian Netherlands didn’t cease to exist after 1477. Walter Prevenier and Wim Blockmans, highly praised and often quoted by Van Loo, have argued in recent decades in a series of publications, intended also for the general public, that the famous Burgundian culture in the Low Countries may well not have peaked until another 50 years later.

With all of this Van Loo offers his readers a wonderful tangle of stories, but he hardly brings them into any kind of structured order. The countless events that he describes with such detail all seem equally important to him. In this way Van Loo gives the book great pace and the reader must, as it were, constantly gasp for breath. But by the end of it, we are left wondering which journey we have actually been on. Judging from Van Loo, the French King Charles VII – thanks to the elusive Joan of Arc – had finally won the Hundred Years War around the middle of the 15th century. By that time Philip the Good had also brought most regions in the Low Countries together under one constitutional structure. But apart from this, nothing much had apparently changed in these regions since the preceding 150 years.

Bart Van Loo has written a wonderful book, which is also beautifully illustrated. With his endless stories he provides insight into the human psyche, and the accompanying timeless emotions such as bitterness, hatred and envy. It isn’t however history in the sense of a structured report on events within a specific period of time.