The Burgundians Show off Their Miniatures in a New Museum

The Royal Library of Belgium (“KBR”) has a unique collection of manuscripts from the Burgundian period. After being hidden for approximately six hundred years, these gems of the Flemish miniature art are now accessible in a new museum on the Brussels Mont des Arts.

Philip the Bold (1342-1404), a mighty monarch and cultivated patron, stands at the beginning of ‘Librije,’ otherwise known as the collection of the Burgundian dukes’ manuscripts. His son, John the Fearless, inherited the library and obtained other manuscripts from the possessions of his grandfather Louis of Male, Count of Flanders, and his uncle John of Berry. The Duke of Berry commissioned, among other things, the beautiful book of hours, which can also be admired in the collection.

Border decoration in the Peterborough Psalter.

Border decoration in the Peterborough Psalter.© KBR

Formed at the crossroads of the Middle Ages and the New Age, the Librije covers all domains of science and thought from the time. It contains classical authors, such as Xenofon or Ptolemy, works on autonomy, law, theatre, chansons de geste, poems by Christine de Pizan. The library of the Dukes of Burgundy is one of the largest libraries of its time, rivalled only by the French kings, the Medici, or the papal library. The manuscripts are illuminated by the best miniaturists of the fifteenth century, some of whom were as famous as Jan Van Eyck.

Jean Wauquelin offers his work to Philip the Good. Miniature of Rogier van de Weyden in ‘Les Chroniques de Hainaut’. Southern Netherlands, 1447-1468

Jean Wauquelin offers his work to Philip the Good. Miniature of Rogier van de Weyden in ‘Les Chroniques de Hainaut’. Southern Netherlands, 1447-1468© KBR

Under Philip the Good, the ducal library expanded considerably. During his reign – which lasted almost fifty years – the power of Burgundy reached its peak. The duke, a fine art lover and bibliophile, commissioned prestigious art works, one after the other. The Chronicles of Hainaut is perhaps the most famous masterpiece in the collection. In a separate display cabinet, the imposing book lies open on the so-called presentation miniature. On it is Philip the Good, dressed in black and wearing the necklace of the Golden Fleece around his neck, depicted upright: an elegant ruler, flanked at some distance by his entourage. The scene is a story within the story of the book. In this miniature, Philip is offered the book itself, the Chronicles of Hainaut, a beautiful piece of propaganda that helped him take control of this region from his cousin Jacoba de Bavaria. The miniature is attributed to Rogier van der Weyden.

The fact that Philip the Good liked to identify himself with great historical rulers is evident from his identification with Alexander the Great, the embodiment of all chivalrous virtues, or the tracts from which his ancestry must be apparent from King Arthur, Charles Martel, Charles the Great. He also dreamed of a crusade to liberate Constantinople. Although this never happened, he read about it a remarkable amount. He was a bibliophile not only for the sake of the literature itself, but he also allowed himself to be surrounded by talented copyists, bookbinders, and miniaturists who had to satisfy his flair with their craftsmanship to strengthen his political aspirations.

Philip the Good allowed himself to be surrounded by talented copyists, bookbinders, and miniaturists

After the death of his son Charles de Bold in 1477, the ducal library consisted of more than nine hundred manuscripts. A third of these miraculously survived a major fire in the Coudenberg Palace and two world wars. They are preserved today at the KBR museum. These fifteenth-century manuscripts are produced by artists who exchange ideas, concepts, and iconographies.

The Burgundian century of Gothic churches, Brabant altarpieces, carpet weaving, polyphonic music, and Flemish Primitives are interconnected in many ways. You can see extraordinary examples of this, such as parallels between the composition in a miniature and a similar painting of the Martyrdom of Saint Barbara.

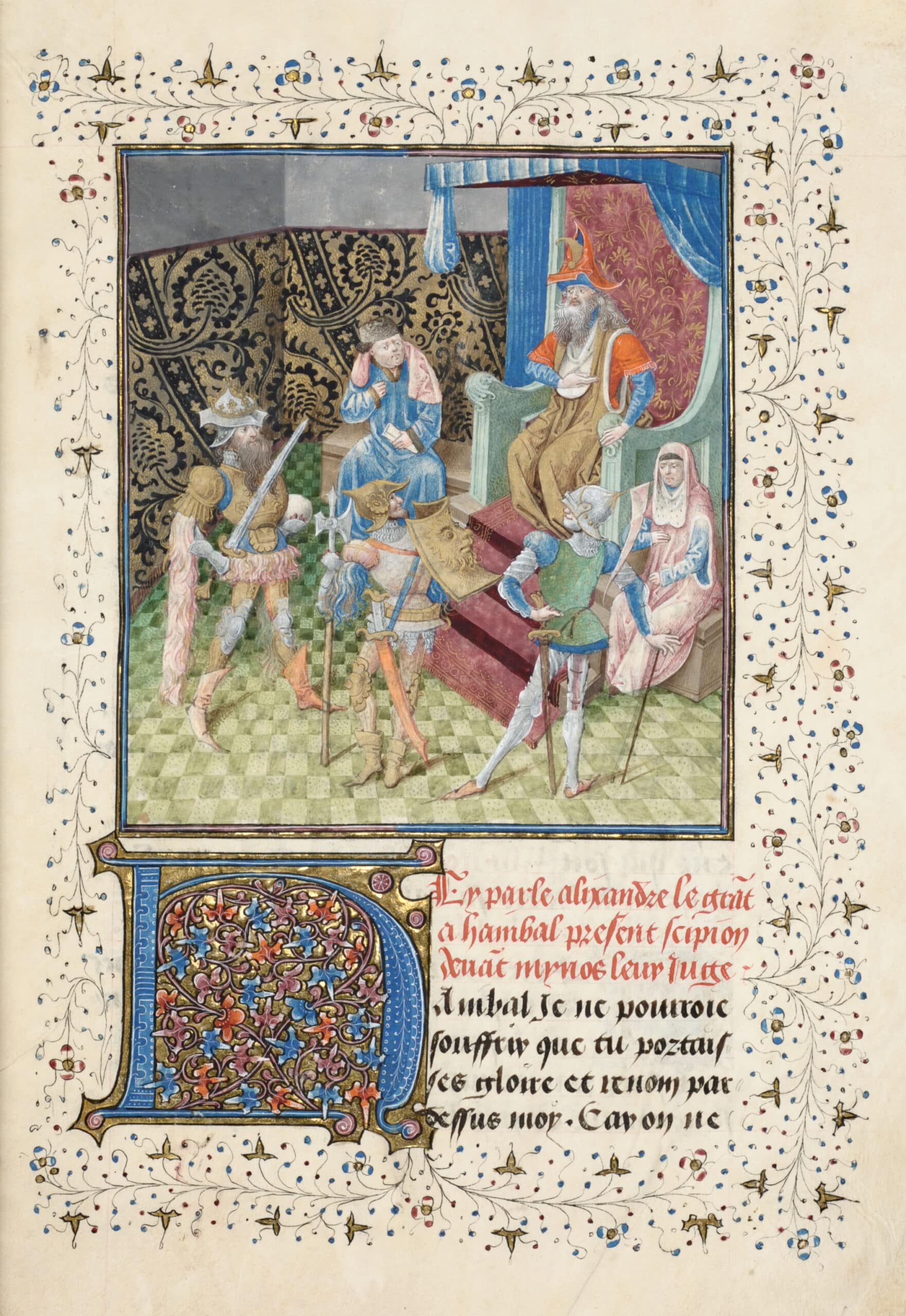

Alexander the Great, Hannibal and Scipio Africanus appear before King Minos to hear from him who is the greatest general. Miniature by Jan Tavernier in ‘Lucien de Samosate, Débat d’honneur’.

Alexander the Great, Hannibal and Scipio Africanus appear before King Minos to hear from him who is the greatest general. Miniature by Jan Tavernier in ‘Lucien de Samosate, Débat d’honneur’.© KBR

Burgundian Bastarda

Abbeys were important places to produce manuscripts during the Middle Ages. The classical image we have of the monk-copyist does exist, but he is by no means the only one who copied medieval texts. Moreover, there were also female copyists, both religious and lay. With the rise of universities, the ateliers of book craftsmen, scriptoria, and bookshops in also began to emerge in cities. The evolution translated into an increased production of profane texts, which appealed to the new clientele in the cities. The demand for books increased and the market began to grow. Manuscripts circulated as a source of ideas and knowledge, but also as a status symbol.

Nobility, clergy, bourgeoisie, and urban authorities all followed the example of Philip the Good, the great Duke of the West. The ducal library reflects whatever interested the rich top layer and it also says something about their own personalities. They placed numerous orders with the ateliers of copyists, illuminators, and bookbinders. The result is a kind of ‘canon’ of the Burgundian luxury manuscript: richly illustrated, a quality binding, a layout with plenty of white space, and a preference for a certain typeface.

© KBR

Handwritten scripts come in many forms. These differ according to place and time, but the chosen script also depends on the function of a text. In the fifteenth century, letters had a different form depending on whether it concerned a missal book, a commercial contract, a novel, or the translation of an antique text by a humanist. As book lovers and trendsetters, the Burgundian dukes had their own type of writing: the Burgundian Bastarda.

In the exhibition, you can see up close how the technical production process of handwriting works, from parchment made from goatskin to an abound and illuminated precious artwork. All steps on how to make parchment and how these differ from those to make paper, are indicated in a tangible way. You can also use a digital ‘quill’ on an interactive screen to try and write a sentence in gothic writing. Based on the ease with which you can do that, the program calculates how long it would take you to copy Jacob van Maerlant’s fully gothic Bible of Rhymes from the thirteenth century. It only increases your appreciation for the precious writings (and for today’s fast-paced technology).

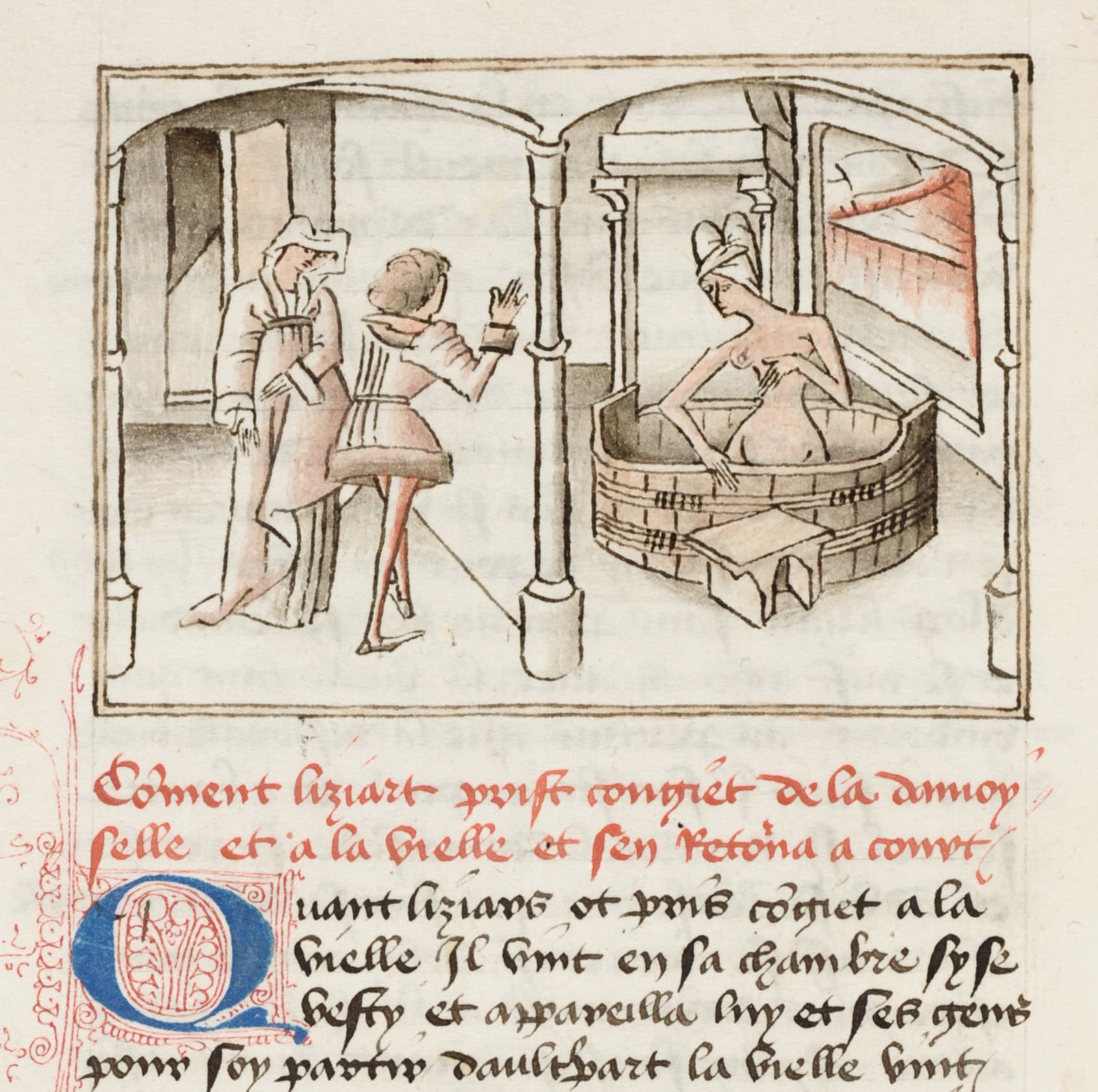

Through a hole in the wall, Liziart spies Euryant in her bath and sees a special spot on her chest. Miniature of the Master of Wavrin in ‘Roman de Girart de Nevers’. Southern Netherlands, 1450-1467.

Through a hole in the wall, Liziart spies Euryant in her bath and sees a special spot on her chest. Miniature of the Master of Wavrin in ‘Roman de Girart de Nevers’. Southern Netherlands, 1450-1467.© KBR

Handwritten treasures

Static objects that demand the almost intimate attention of the individual visitor, it is not easy to make manuscripts attractive to a large audience. Yet the interactive trail makes a successful attempt, available in five languages and developed for three different profiles (a short explanation for children, a concise summary for the discoverer, and a more in-depth explanation for the more interested visitors). But above all, the scenography and the colours, designs, and materials comprising the treasure chamber, immerse you in the late Middle Ages. The polyphonic music intensifies this experience, as do the atmospheric projections with which the trail begins in the restored Nassau Chapel, the last real remnant of the Burgundian court in Brussels.

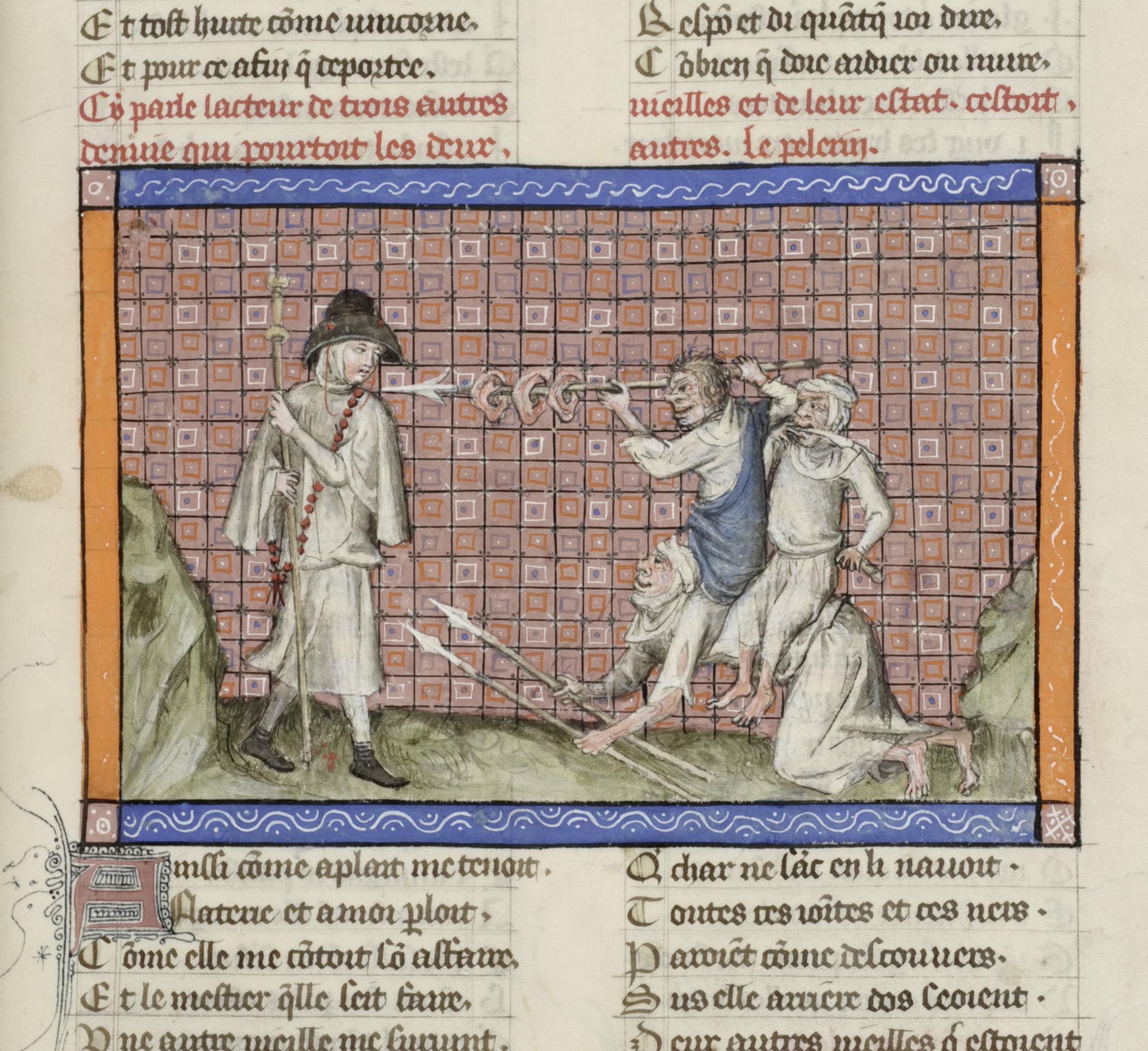

The pilgrim in confrontation with Envy, with her two daughters Denial and Betrayal on her back in ‘Guillaume de Digulleville, Pèlerinages’. North of France, ca. 1400.

The pilgrim in confrontation with Envy, with her two daughters Denial and Betrayal on her back in ‘Guillaume de Digulleville, Pèlerinages’. North of France, ca. 1400.© KBR

It is richly furnished, but the focus remains on the manuscripts themselves. It is a somewhat undervalued art form; manuscript illuminators were not regarded as fully-fledged artists. However, these artefacts are not only rich in content, they are also enormously artistic. In addition to great craftsmanship and an intensive production process, manuscripts connect art forms, giving them a unique layering. The interaction between word and image, the references to religious, mythological, historical background, choral music scores… it requires an attentive engagement of the viewer.

The lavish use of beautiful colours and gold that endure time, the many details in decorations and patterns, or the drolleries (those funny or grotesque fantasies in the page margins), provide insight into the very multifaceted past. The Van Hulthem Manuscript, a masterpiece of medieval Dutch literature, unique historical works that have determined the history of literature as the Brabant Yeasts by Jan van Boendaele, the Roman de Renart, the first French fiction text Roman de la Rose, the self-written work The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis; this collection is indeed a treasure.

Battle of the consul Marcus Actilius and the mythical beast. Miniature by Willem Vrelant in ‘Leonardo Bruni, Première guerre punique’.

Battle of the consul Marcus Actilius and the mythical beast. Miniature by Willem Vrelant in ‘Leonardo Bruni, Première guerre punique’.© KBR

The KBR has chosen ‘Cherish the time’ as their new slogan. Conservation preserves time for the future. It is convenient that this no longer has to be done in archives purely on request but is now being introduced in the new museum by means of loans. For instance, for the first time, there are collaborations between the library and other museums such as the Hof van Busleyden in Mechelen, or the Gruuthusemuseum in Bruges, which are thematically covering the same period, with which the KBR can provide more in-depth information with written sources.

As a ‘living museum,’ the exhibits are changed three times a year, also due to the fragility of the manuscripts. Tourism Flanders is very fond of the ‘authentic heritage experience,’ which sometimes makes one fear for the tumult that has to attract the masses. The new KBR museum maintains an air of serenity and knows how to focus on the manuscripts, which makes the rediscovery worthwhile. Was it not also that, in the margin of a manuscript, Dutch literature came into being?