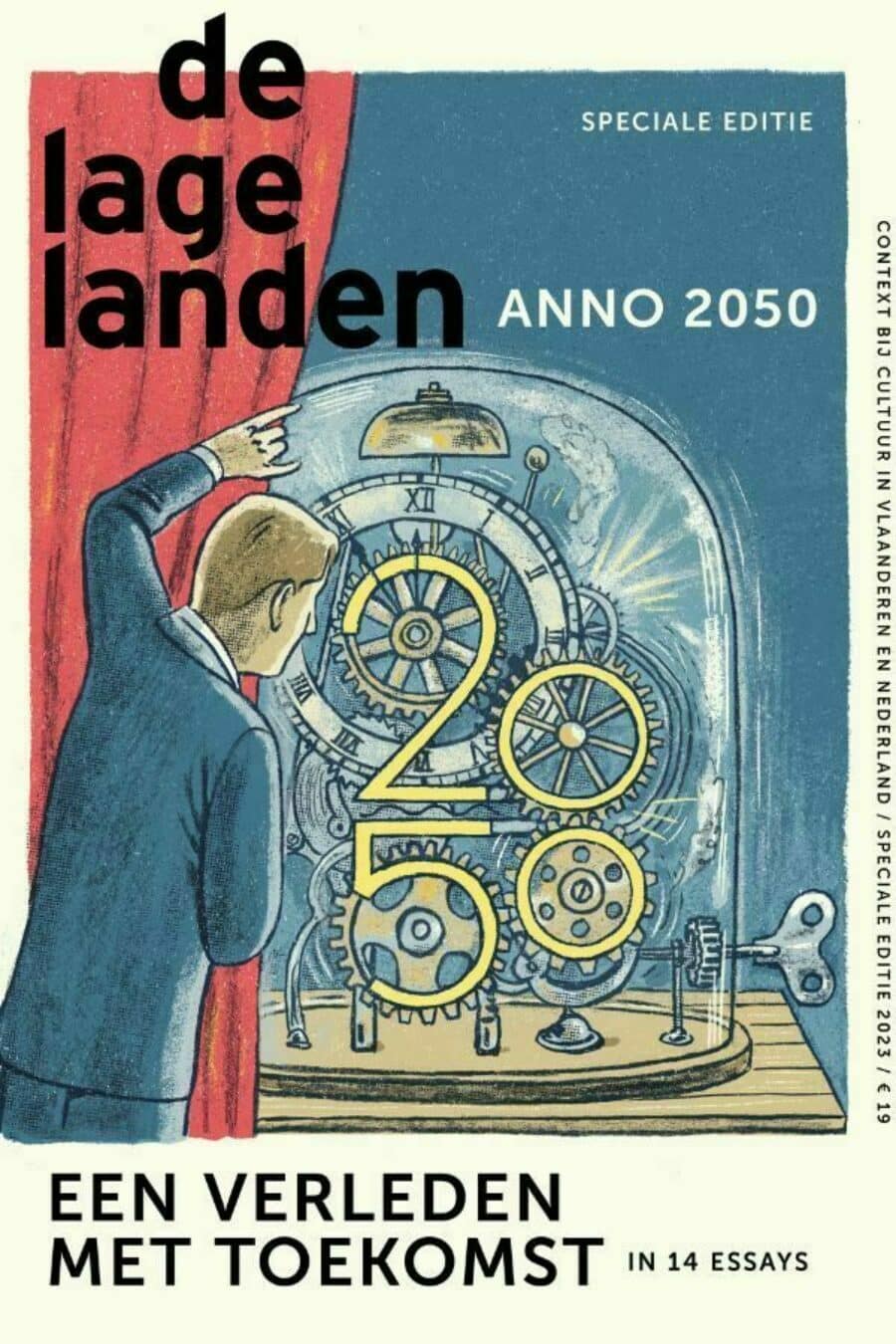

The Dutch Language in 2050? More Diverse Than Ever

Will the Dutch language still exist in the future? Linguist Marten van der Meulen addresses this question, as we specified, in the book The Low Countries in 2050: A Past with a Future. His response, written as if it’s already 2050, is also available here. “Let’s discuss Dutch, considering its plural form.”

Does the Dutch language have a future? This was a frequently asked question in 2023. To the casual observer, it appeared to be an acutely relevant question. There was an increase in English words in Dutch newspapers, a growing number of international students communicating and being taught exclusively in English, and a decline in Dutch book titles alongside a rise in English ones on bestseller lists. Murmurs of discontentment and worry filled the air: people were worried. Could it really be the end for the language of Bredero, Hella Haasse, Urbanus, Anton de Kom, K3, and Aletta Jacobs? Was our language, with its rich history, on the brink of vanishing? Only time would tell.

Could it really be the end for the language of Bredero, Hella Haasse, Urbanus, Anton de Kom, K3, and Aletta Jacobs?

Yet, people tend to forget things so quickly. All those sceptics overlooked that the exact same scenario had been predicted in 1980. Back then, Dutch was also expected to rapidly decline. Similar claims were made in 1930 and 1950, and this pattern extends far back into the nineteenth and eighteenth centuries, echoing through time. Dutch was consistently forecasted to deteriorate or disappear in the foreseeable future. Now, it’s the English language that plays a leading role in shaping Dutch to resemble itself. In earlier times, the German language played a similar role, and before that, it was the French language. Essentially, the fear of losing Dutch has always been directed towards the language of the dominant political and economic culture in the Western world, a language introduced in a Trojan horse manner.

Was the fear of losing our language ever justified? No, never. Like a storm, various languages swept across the Dutch-speaking region. They disrupted the foundations of our language by uprooting sound trees and redirecting the flows of sentence rivers. However, when the skies cleared, and people stepped out of their homes, they noticed that, despite the appearance of unfamiliar word blossoms, it was still their familiar landscape. The landscape of the Dutch language may no longer resemble the language of a thousand years ago, after all the storms and shifts. Nevertheless, it has always retained its unique and recognizable identity.

Words, words, words

In 2050, things remain much the same. The Dutch language hasn’t undergone fundamental changes since 2023, yet it’s not entirely the same. Neither in its appearance, form, nor usage has it changed entirely. What always stands out the most is its vocabulary. New words follow the trends of popular cultural expressions and new technologies, seamlessly integrating into the language. This process happened thousands of years ago as part of Roman domestic innovations. As a result, we still use words like kelder (cellar), zolder (attic), and keuken (kitchen), derived from the Latin cellarium, solarium, and cocina. It has continued with words like computer, pizza, volgasvoetbal (full-throttle football), and countless others. In recent decades, this phenomenon has included an increasing number of words from English, as well as from Korean, Tamazight, Mandarin Chinese, and Ukrainian. These new source languages reflect gradual shifts in culture, cuisine, sports, music, politics, technology, and literature, introducing different subjects to new areas.

Words, words, words. It looks like there are so many, it’s overwhelming, but they are not a threat to language. Where the language did face pressure was not in the incorporation of foreign words into a sentence but in having entire sentences, or even entire conversations, in another language.

In 2023, we saw a mixed picture. On one hand, Dutch was exceptionally strong, with more speakers than ever before using it in politics, media, and social interactions. On the other hand, concerns arose over the disappearance of Dutch literature and the increasing influx of international students, a result of ongoing higher education liberalization. While there was no immediate cause to worry, these developments raised questions about their long-term benefits for both society and the Dutch language. A socio-cultural division of languages, much like the historical division between French and Latin on one side and the “local” languages on the other, was coming into view.

Finally, thousands of students in international Dutch studies, who explored our language and culture from Brno to Seoul, received the recognition they deserved

Fortunately, between 2030 and 2050, governments made significant efforts to support the Dutch language through political and economic decisions. The higher education sector was a primary focus, with Dutch studies receiving increased support both nationally and internationally, in terms of funding and recognition. The term “non-vocational study” disappeared and it was finally recognized that the study of the Dutch language, culture, literature, and identity not only contributed to a socially, culturally, and economically rich, productive, and prosperous society, but was indeed essential to it. Finally, thousands of students in international Dutch studies, who explored our language and culture from Brno to Seoul, received the recognition they deserved. Seemingly trivial matters, such as facilitating and encouraging the use of Dutch terminology in the medical, legal, and scientific domains, demonstrated vision. The same goes for improved salaries, more evident dedication, and the increasing social esteem of translators. In this way, Dutch was safeguarded for the future in various ways.

Diversity within unity

In 2050, Dutch is flourishing like never before. However, can we still call it Dutch today? Well, not quite. It would be more appropriate to now refer to it as Dutches in the plural form. Much like English’s diversification into global varieties (World Englishes) in the late 20th century, characterized by various regional accents and forms, the same transformation has consistently continued for Dutch in the 21st century. This shift was a result of an increased awareness of the pluricentric nature of the Dutch language. Dutch has three central points: the Netherlands, Flanders, and Suriname. The variety spoken in the Netherlands is not considered superior to the others. Recognizing this, a longstanding commitment was fulfilled to grant Surinamese Dutch its rightful status as a fully developed language variation, coexisting with both Belgian Dutch and Dutch spoken in the Netherlands, without being subordinated to either. The recently completed Grote grammatica van het Surinaams-Nederlands (2045) (Comprehensive grammar of Surinamese-Dutch) played a crucial role in this process.

An inevitable consequence of the increased self-awareness of these three varieties was that they began to drift apart. The pace of this divergence resembled the slow drift of tectonic plates, but the development was unmistakable. The process also revealed an interesting paradox. While differences in language between countries were slowly increasing, they were decreasing within countries, especially on a geographical level. Regional dialects, local languages, and dialects became increasingly logical casualties of the struggle between local and global influences. In a world where geographical stability was becoming less certain, other elements of language became stronger markers of identity, such as the language of your workplace or your social circle. Through these, people distinguished themselves and displayed the colours of their identity.

© Pexels

A final way in which people distinguished themselves in language surged in the years leading up to the halfway point of the century. The so-called ethnolect, a language variety spoken by people with a shared ethnic background, experienced significant growth. This phenomenon wasn’t limited to the Netherlands, it occurred worldwide as a result of constant migration, whether forced or voluntary. Within the Dutch-speaking region, in addition to older ethnolects such as Turkish-Dutch and Moroccan-Dutch, new ones like Eritrean-Dutch and Sudanese-Dutch emerged. Here too, we can observe how the concept of Dutches

is taking a firmer shape. The old biblical concept of diversity within unity finds its modern application in the realm of language.

The acceptance of all these forms of Dutch can be placed under an even larger umbrella. No longer was there a narrow view, as formulated in the once common political slogan “In the Netherlands, we speak Dutch.” Two words with a massive impact brought about a fundamental shift: “Dutch and…” Dutch-Dutch and Belgian-Dutch, and Surinamese-Dutch. Standard Dutch and ethnolects. Dutch and room for other languages. In addition to English, we also embraced the well-established companion languages French and German, along with newcomers like Polish, Turkish, Arabic, and Mandarin Chinese.

Multilingualism offers numerous social advantages, promotes mobility and flexibility, and even brings cognitive benefits

The 19th-century Eurocentric nationalism, which advocated for “one language, one country,” eventually gave way to the globally prevailing norm of multilingualism. Hand in hand with this shift came the hard-earned realization that multilingualism is beneficial for society. Furthermore, the coexistence of multiple languages, similar to the diversity of residents, does not undermine the national character; instead, it keeps it vibrant. Multilingualism, in any combination of languages, offers numerous social advantages, promotes mobility and flexibility, and even brings cognitive benefits.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, it was a common practice in the Netherlands and Belgium to metaphorically depict language as a garden. In works such as Taaltuintjes (Language Gardens), Onkruid onder de tarwe (Weeds among the wheat) and In de Nederlandse taaltuin (In the Dutch Language Garden), authors identified linguistic weeds and suggested methods to eliminate them. All of this was done with the aim of creating a tidy and well-kept garden, though one that was pale green and lacking in diversity.

But over time, our perspective on the language garden began to change. Just as we’ve learned from modern ecological insights that what we once considered weeds can actually be a valuable food source, we’ve also come to realize in the realm of language that embracing diversity is better than trying to eliminate it. It’s about recognizing the advantages of those linguistic plants that were once labelled as weeds. It’s about allowing a profusion of expressions to flourish. All of this ensures that the Dutch language, in all its forms, will maintain its position in the next hundred years and beyond.

The book The Low Countries in 2050: A Past with a Future (in Dutch) is priced at €19 and available for purchase on de-lage-landen.com.