The Dutch Origin of the Pinkster Festival in America

Every year, on the seventh Sunday after Easter, Christians celebrate Pinksteren (Pentecost). However, Pinkster is an African American holiday in the Northeastern United States. During the 17th and 18th centuries, enslaved and free African Americans transformed Pinkster from a Dutch religious observance into a spring festival and a celebration of African cultural traditions. It is still celebrated every year in America. No other Dutch tradition represents better the utopian vision of a harmonious society than New York’s Pinkster festival.

The earliest reference to a Dutch Pinkster celebration in America dates back to 1655, when the Court of Fort Orange gave permission to the burgher guard of Beverwijck, the later Albany, to organize papegaaischieten (parrot shooting) on the third day after Pijnghsteren (Pentecost). Later sources confirm that Pinkster continued to be celebrated until the mid-nineteenth century in areas in New York and New Jersey that once formed New Netherland. American sources on Pinkster all confirm the massive participation of African Americans, to such a degree that in the nineteenth century it was primarily perceived as a celebration of the black community.

James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851)

James Fenimore Cooper (1789–1851)The most famous description of an American Pinkster festival was provided by James Fenimore Cooper, author of the historical novel The Last of the Mohicans (1826). Since he spent his childhood in Upstate New York, where the Batavian bastion Albany was the nearest city, Cooper was quite familiar with Dutch culture. His wife Susan De Lancey also had close relatives in Fishkill who were of Dutch heritage. In the spring of 1828, Cooper visited the Low Countries for the first time and he later returned there twice, in 1831 and 1832.

In his novel Satanstoe (1845), set in the mid-eighteenth century, Cooper describes the Pinkster festival through the eyes of Cornelius – ’Corny’ – Littlepage, a New Yorker of mixed English-Dutch descent. During his visit to New York City on Pinkster day, Corny is accompanied by two friends, one of whom, Dirck Van Valkenburgh, is of Dutch descent, while the other one, Jason Newcome, is a New Englander from Connecticut.

Cultural differences

According to Corny, one of the most notorious differences between New Yorkers and New Englanders is the distinctive way in dealing with people of other races, because ‘there is something in the character of these Anglo-Saxons that predisposes them to laugh, and turn up their noses, at other races,’ whereas ‘among the Dutch, in particular, the treatment of the negro was of the kindest character.’ The cultural differences between the friends are notable in the description of the festival. While Dirck and Corney are familiar with the African-American Pinkster attractions, Jason was ‘confounded with the noises, dances, music, and games that were going on’.

Anti-Rent Movement

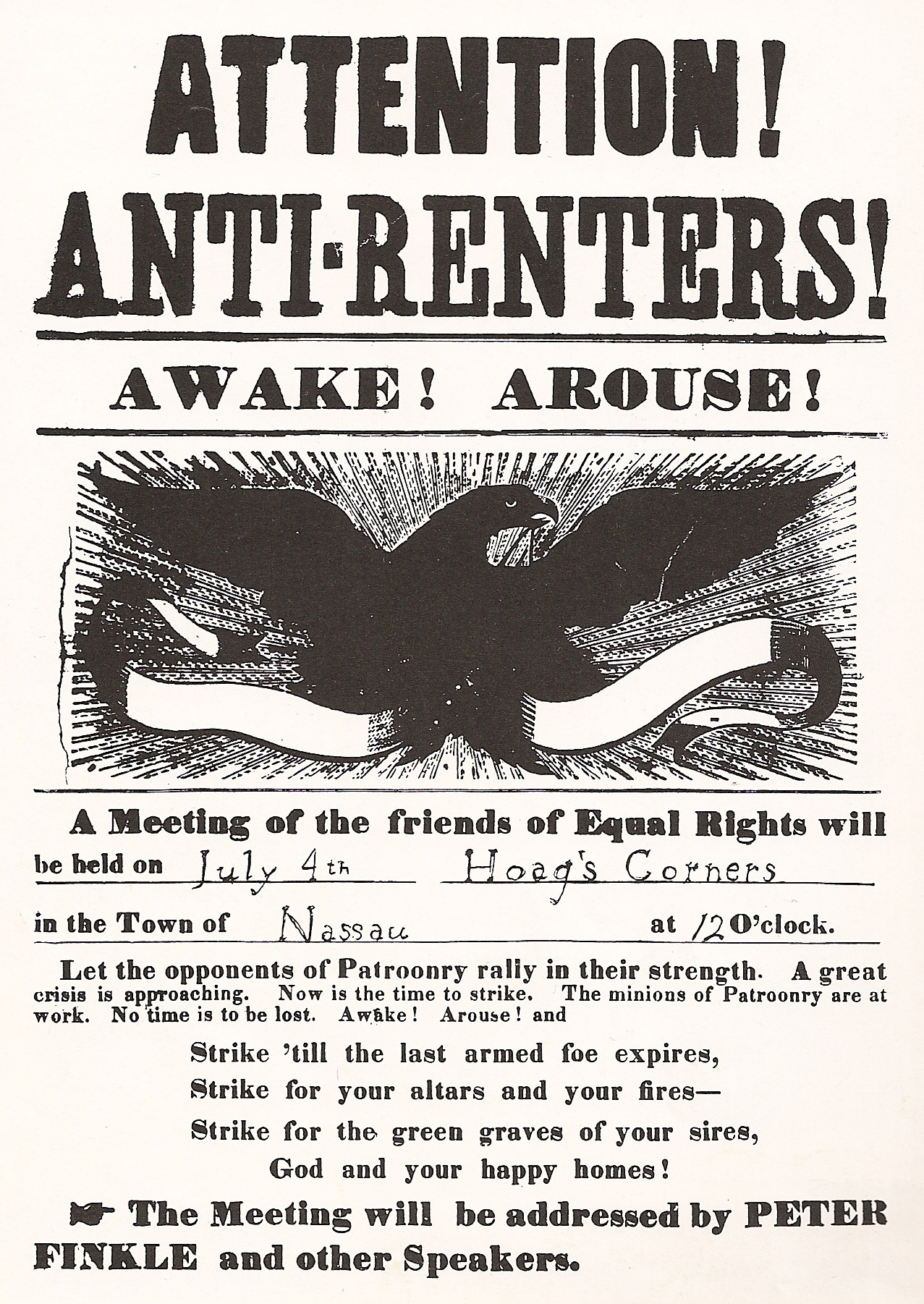

Poster announcing an Anti-Rent meeting in the town of Nassau, New York, 1839

Poster announcing an Anti-Rent meeting in the town of Nassau, New York, 1839© Rensselaer County Historical Society

Cooper’s interest in Pinkster is connected to the ‘Anti-Rent War’ that began with the 1839 death of Patroon Stephen Van Rensselaer, whose tenants owed him 400,000 dollars. When Van Rensselaer’s sons attempted to collect these debts, the tenants bluntly refused to pay. After the Judiciary Committee had sided with the landlords in an 1842 decision, angry tenants formed the ‘Anti-Rent Movement’ that violently resisted legal action. The movement grew considerably in the next decade and gained political importance when anti-renters decided to back specific candidates, both Whigs and Democrats, who favored their positions. Cooper, who was personally acquainted with some of the land-owning families involved in the dispute, considered anti-rentism ‘the great New York question of the day’. He felt that the anti-renters’ behavior represented an opportunistic distortion of republican principles that represented a threat to the nation’s future.

Focus on Dutch heritage

In Satanstoe, Cooper reacted to the anti-rent war by marking the difference between two types of America, one with an exclusively English background as opposed to one with a Dutch-English background, or what he called ‘a melange of Dutch quietude and English aristocracy.’ Irritated by what he considered to be the populist, selfish behavior of the anti-renters, Cooper focused on America’s Dutch heritage in order to distinguish between New Englanders, who essentially interpreted the notion of freedom as individual freedom in an Anglo-Saxon tradition, and New Yorkers, whose understanding of freedom had been shaped by the Dutch community-oriented mentality in a bourgeois tradition.

Pinkster Festival in Sleepy Hollow, New York

Pinkster Festival in Sleepy Hollow, New York© Tom Nycz

Tolerant Dutch mentality

Omitting the fact that, in places such as Suriname, Dutch slaveholders were considered among the cruelest in the world, Cooper interpreted the treatment of slaves owned by Dutch-American families as a reflection of the tolerant and community-oriented Dutch mentality. The English refusal to consider slaves to be part of their own community, on the other hand, reflected the same problem that was at the heart of the Anti-Rent War: the evolution of the United States into a nation where citizens do not perceive themselves as brothers and sisters of one and the same community but rather act as selfish individuals.

Pinkster Festival at Sleepy Hollow, New York

Pinkster Festival at Sleepy Hollow, New York© Tom Nycz

Idealising the Netherlands

Cooper’s Satanstoe stands, as such, at the beginning of what would become a tradition in American literature – from Mary Mapes Dodge’s Hans Brinker (1865) to Russell Shorto’s Amsterdam (2013) – to idealise the Netherlands as a nation characterized by a strong commitment to tolerance, diversity and solidarity and to use this image as a mirror for readers in the United States. Due to New York’s Dutch heritage, this strategy did not simply have a comparative value but rather served as a vision of what America could have been. No other Dutch tradition better represented this utopian vision of a harmonious society than New York’s Pinkster festival.

This article was first published in the yearbook The Low Countries, 2014, № 22.