The Experience Machines of Philip Vermeulen

During his youth, Philip Vermeulen (b. 1986) was overwhelmed when he saw trees that looked like they were invading his house. The artist from The Hague now builds such overwhelming experiences himself, in the form of large installations. You won’t find sensationalism in his work, but you will find an attitude that is as playful as it is investigative.

It started with a piece of tarpaulin, fluttering in the wind. The fluttering movement and sound fascinated Philip Vermeulen. After a lot of testing and playing, Flap Flap (2018) was born: A bar that can be steered so that a large piece of sail moves up and down – which causes a lot of noise.

The movements can be programmed so Vermeulen therefore speaks of a composition or choreography: words that seem to be at odds with “playing” and “testing”. However, this fits in perfectly with the great paradoxical nature of his work: he seems to want to provoke emotional reactions in a rational way.

Philip Vermeulen, Flip Flap, 2018

Philip Vermeulen, Flip Flap, 2018© Philip Vermeulen

Sense of danger

Vermeulen’s installations are strongly rooted in two art traditions that are, at first sight, difficult to reconcile. On the one hand he is indebted to kinetic art, the rather unclearly defined art movement that includes moving art works as well as light art and op-art. This movement included a wide variety of artists – from introverted painters to machos who built installations – they did often share an interest in science, specifically the connection between the eye and the brain.

Philip Vermeulen

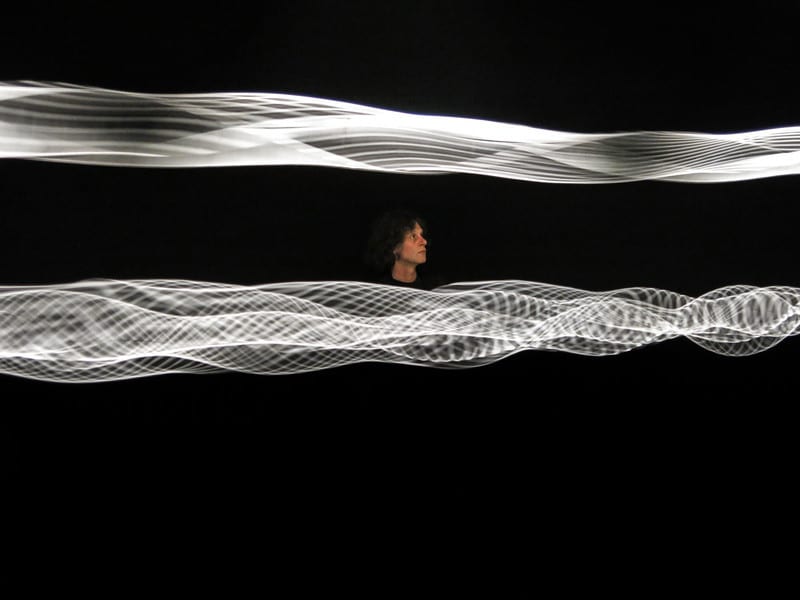

Philip VermeulenSuch that objective art could be created that everyone would experience in the same way. Occasional facial illusions can be seen in Vermeulen’s 10 Meters of Sound (2014-2018), which was purchased by Rijksmuseum Twenthe in Enschede. Four elastic bands, ten meters long, spinning round and starting to undulate, thereby creating moiré patterns. After a while they follow each other at high speed, so that they become almost incomprehensible: what you just saw is gone within a second.

Philip Vermeulen, 10 Meters of Sound, 2014-ongoing

Philip Vermeulen, 10 Meters of Sound, 2014-ongoing© Philip Vermeulen

In addition, the cords provide a sense of danger. The deposition keeps you at a distance, but the feeling of ‘what if they burst?’ remains. This feeling links Vermeulen’s work with another tradition: that of the sublime, the simultaneous feeling of fear and admiration. In 2015, for example, the Rijksmuseum Twenthe devoted an exhibition to William Turner, the nineteenth-century painter known for his imposing landscapes and representations of natural disasters. Whereas Turner depicted experiences – or perhaps even earlier: passed them on – Vermeulen is creating them.

His installations are nothing, in the sense that they are not representations of a shipwreck or mountain landscape, for example. At the same time, it is difficult to call them truly abstract when they present themselves to the viewer in such a large way: a considerable sail, large elastic bands, tennis balls that shoot through space in a roaring motion. They are simply devices that can evoke strong reactions and experiences.

No matter how much Vermeulen experiments and tries new things in his warehouse, what matters to him are spectators that react to the installations. In addition to the sublime, he would also like to capture ecstasy in his work: the intense emotion that he describes as the moment when you seem to be one with everything around you.

PolyDrip (2016) is an audio visual live instrument. Made on behalf for the composition 'Klepsydra' by Kate Moore. Two automated ink drippers drip from the ceiling on amplified dishes. The dishes are build in aquaria. The ink sublimates the water in ink patterns into an immersive abstract landscape.

PolyDrip (2016) is an audio visual live instrument. Made on behalf for the composition 'Klepsydra' by Kate Moore. Two automated ink drippers drip from the ceiling on amplified dishes. The dishes are build in aquaria. The ink sublimates the water in ink patterns into an immersive abstract landscape.© Philip Vermeulen

Vermeulen was a student at a more traditional art academy for two and a half years (including repeating one year as he stayed back a class, he notes), but he didn’t feel at home. He was too much of a loose cannon that wanted to continuously experiment, he says. In retrospect, he also found that the art history taught at the academy was too limited. Little attention was paid to kinetic art, not to mention film and sound. He did find his way to the ArtScience Interfaculty in The Hague, an interdisciplinary collaboration between the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague (KABK) and the Royal Conservatoire. Research and technology play important roles here, as do cross-pollinations between visual arts, music, theatre and film. The first time Vermeulen heard about the faculty, was when someone told him about an art school where students had to push pencils into their eyes and then draw what they saw. He quickly realized that’s where he had to go, he says laughingly.

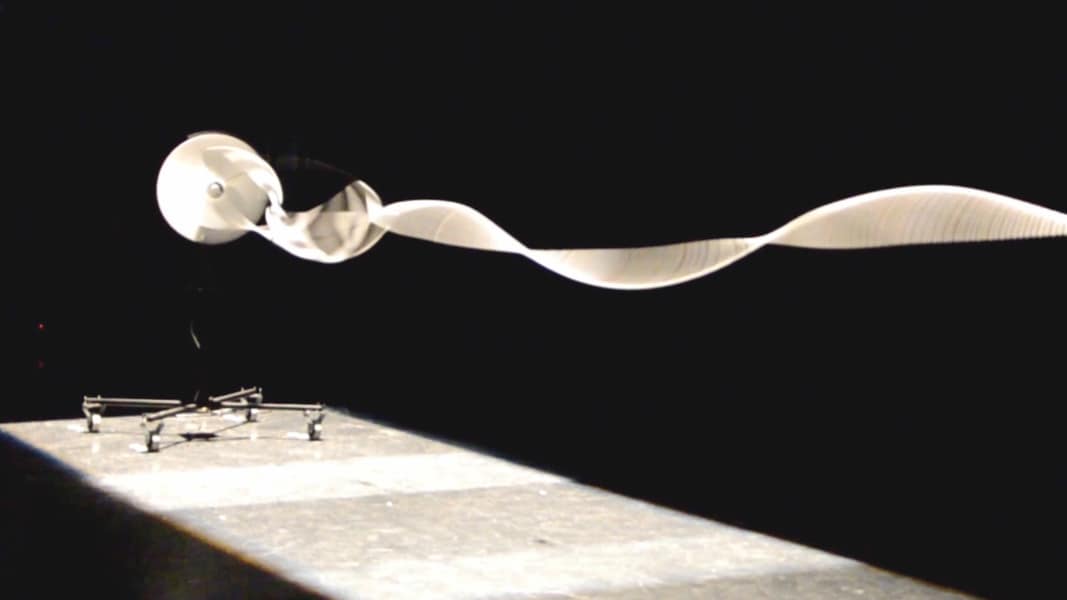

Fan (2013) is a self-destructive mobile. When turned on the fan is rotating the elastics alternately until the elastic is completely climbed letting the the fan move towards certain death.

Fan (2013) is a self-destructive mobile. When turned on the fan is rotating the elastics alternately until the elastic is completely climbed letting the the fan move towards certain death.© Philip Vermeulen

While being at ArtScience, Vermeulen wrote his thesis on sublime: Brewing the Sublime (2017), which is a cross between a cookbook and a long essay; later published in book form. The book tells the story of him as a child staring out of the window and seeing the distance between him and the trees outside constantly changing. The trees seemed to slowly enter the room: “I panicked a little, but I was also very happy to see and experience this”. Later, he recognized the same feelings when viewing artworks by Mark Rothko, Yves Klein, and Kurt Hentschläger. He was able to disappear into their works, and in his own work he strives for the same feeling of immersion.

This is followed by an exploration of the various definitions of the sublime, and the question of whether and how you can evoke this phenomenon. The text regularly contains recipes, but there is no conclusive method. It remains a matter of experimentation: “Discover different ingredients in all kinds of media: sound, light, physics, nature. Try to cook with them by adding them in extreme quantities. When does it cook, when does it burn?” The often-absurd recipes show how impossible this undertaking is: for one recipe, for example, mountains, seas, and even universes have to be blended.

No sensationalism

In his thesis, Vermeulen also criticizes Rain Room by art collective Random International, an installation that tries to create an impressive experience by letting visitors walk in the middle of a downpour while they don’t get wet. The designers do not want to reveal exactly how it works, because of the magic – which Vermeulen dismisses as ‘Disney-like’. This criticism says a lot about his own attitude, which has something honest and inquisitive. Even without technical knowledge, it is easy to see how his installations function. This honesty keeps the pursuit of sensationalism at a safe distance. This, moreover, is one of the beautiful contradictions in Vermeulen’s work: it is clear which ingredients the artist uses, but that only becomes apparent later on. At the moment itself, you just let yourself be carried away.

One of Vermeulen’s main ingredients is sound. Few things evoke such a direct reaction as a sudden blow or bang: few feels so overwhelming as constant noise. Physical Rhythm Machine / Boem Boem (2017) is one of Vermeulen’s most famous works, which he created during his graduation from ArtScience. It was later shown in art institutions, at media art festivals and at a pop festival. Tennis balls are shot at 150 (!) kilometers per hour against wooden sounds boxes, after which there are popping noises. Vermeulen instructs visitors where they can walk to stay safe, but it remains a bit tricky: moving too far from the path can have unpleasant consequences.

Philip Vermeulen, INT/EXT, 2018

Philip Vermeulen, INT/EXT, 2018© Philip Vermeulen

The fact that Vermeulen’s ingredients can be easily recognized, is because he likes to tear them apart, isolate them; thereafter strengthen or change them. This has to do with his interest in public reactions. He is not interested in objective art: the subjective experience is much more interesting. He cites INT/EXT (2015) as an example, an installation that seems atypical to him – at least at first sight. In a completely dark space, a small amount of light suddenly begins to shine, evoking highly subjective after-images. Likewise, the artwork evokes different reactions: it made three people cry – more through panic than emotion – while it left others indifferent. This does not mean the installation has failed: it more so provides an opportunity to continue playing, experimenting, and tweaking. The new version of INT/EXT should make even more people cry, Vermeulen jokes. An installation that makes everyone feel exactly the same, perish the thought! Because what else could he do next, he wonders.