The Forgotten Battle of the Belgians and the Dutch in the Korean War

After North Korean troops invaded South Korea on 25 June 1950 the United States quickly called upon the United Nations for support. Shortly afterwards, Belgium and the Netherlands also sent soldiers to Asia. Eventually, nearly eight thousand volunteers from the Low Countries fought in the Korean War. For their efforts, the United States awarded them the highest military honours, but back at home, their valour has been virtually forgotten.

Initially, Belgium and the Netherlands were not enthusiastic about supporting the United States in its crusade against communism on the other side of the globe. They had other problems. The Belgian government first wanted to meet its obligations to the recently established NATO. For example, the army had to be reorganised to fit into the structure of this new, international alliance. During that process, Belgium did not want to send experienced troops away from home, certainly not when a war could potentially break out in Europe. Then there was the Koningskwestie (King’s Matter), which reached its peak at that time and toppled the Duvieusart I government in July 1950. The new Pholien government did decide to send troops to Korea but, because the Belgian constitution did not allow for enlisted military personnel to be mobilised for overseas operations, Belgium sent an infantry battalion comprised solely of volunteers.

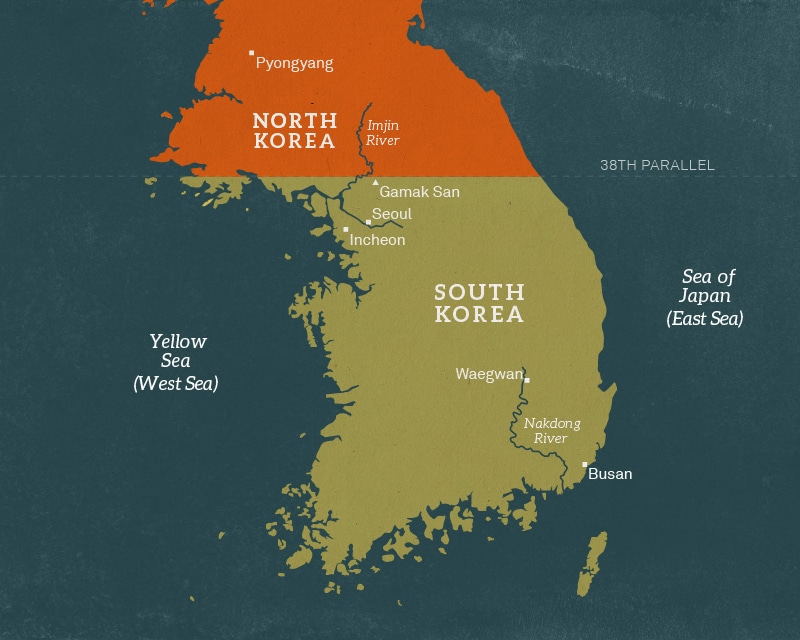

Map of the Korean peninsula, 1950

Map of the Korean peninsula, 1950© National Army Museum, London

Meanwhile, the Dutch police actions in Indonesia had recently ended and the government was eager to invest in the reconstruction of the country rather than in a war far from home. Prime Minister Willem Drees expressed his fears that the Korean conflict could develop into a new world war. The Americans were not sympathetic and threatened to withhold Marshall Plan aid to the Netherlands. To appease the Americans, the government decided to send the torpedo gunboat ‘Hr. Ms. Evertsen’ and an ambulance to Korea. Then, on 17 July, the Dutch agreed to send troops – but solely volunteers.

The criteria for acceptance were strict. Dutch volunteers had to be between 19 and 35 years of age, with prior active duty experience. When the recruitment drive seemed remarkably successful, they added an extra criterion that volunteers should have already had experience in a tropical climate, thus giving preference to soldiers who had seen active duty in Indonesia. After the first selection and training sessions, 627 Dutch and 781 Belgian (including 82 Luxembourgers) volunteers were sent to Korea. Over the course of the entire Korean War, 4,748 Dutch and 3,171 Belgian volunteers took part in the fight.

Paratroopers drop from U.S. Air Force C-119 transport planes during an operation over an undisclosed location in Korea, in October of 1950.

Paratroopers drop from U.S. Air Force C-119 transport planes during an operation over an undisclosed location in Korea, in October of 1950.© Flickr

Loyal to the motherland

The motivations of these volunteers varied immensely. Some went for the sake of adventure, some for the ideal of stopping the spread of Communism. A significant group answered the call for economic reasons. After the Second World War, unemployment was extremely high and doing a tour in Korea allowed soldiers to earn a good income, thanks to the extra danger pay.

Amongst the Dutch volunteer troops there was a group that had already fought in Indonesia. Upon their return from the field, these soldiers had not received a warm homecoming from the Dutch population due to the negative press coverage of some of the army’s excesses. Because they felt they could not re-integrate into regular civilian life, they decided to sign up for another tour of duty, where they would be likely to find camaraderie.

Young volunteers who had been in Japanese internment camps as children during the Second World War joined up for a similar reason. Their traumatic experiences fell on deaf ears back at home in the Netherlands, where the population was concerned only with their own experiences under the German occupation. To escape the apathetic response of the Dutch population to their plight, and to earn money, they signed up for active duty in Korea. This decision was not taken lightly. In the internment camps, the South Korean guards had often been crueller than the Japanese guards. And now they were being asked to go help the Koreans.

Finally, amongst the Belgian and Dutch volunteers were men who had collaborated with the German occupiers during the Second World War or had even fought on the East Front for Germany. They were encouraged to volunteer because service would offer them an opportunity to prove their loyalty to their homeland. At least one Belgian volunteer wrote in his application that he hoped to be taken on as a volunteer ‘to make up for my previous offenses against my homeland and, if I return from Korea, to apply for my reparation, and once again become a worthy Belgian.’

Cold Korean winters

The Belgian volunteer corps left for Korea on 18 December 1950 on the ship ‘Kamina’, arriving on 31 January 1951. In command was Lieutenant-Colonel Albert Crahay. The first volunteers from the Netherlands served under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Marinus Den Ouden, travelling to Korea on ‘Zuiderkruis’ on 26 October. On board, the Dutch soldiers received rudimentary training, including some lessons in Korean culture from Captain Frits Vos. Vos was a lecturer at the University of Leiden and would later become the founder of its Faculty of Korean Language and Culture.

Belgian soldiers during the battle of Chatkol, 1953.

Belgian soldiers during the battle of Chatkol, 1953.On route to Korea, the ship collected volunteers from Turkey and Ethiopia. There was a concern amongst the Dutch troops that they might be confronted with policing work and not allowed to engage in any actual fighting because the reports from the front were mostly encouraging for the UN forces at this point. Upon arrival, however, they heard that the Chinese volunteer army had become involved and the UN army was being driven back.

The Belgian and Dutch soldiers and staff also realised that they had underestimated the hard winters in Korea. They had mistakenly assumed that Korea had a humid, tropical climate. In fact, the winters were frigid, with temperatures of -10 not uncommon. The volunteers arrived without winter clothing and had to be supplied with proper equipment by the Americans.

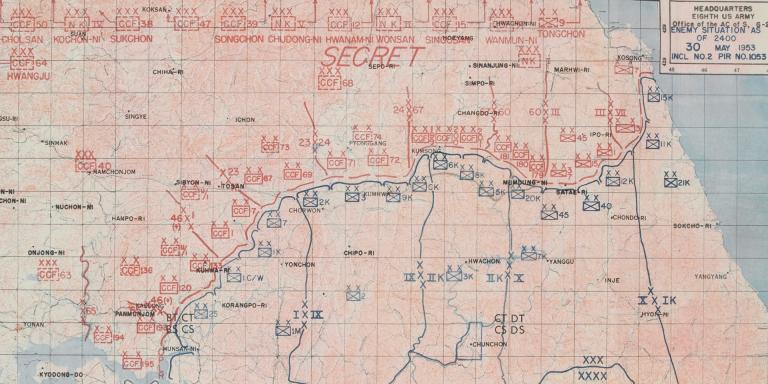

US map of Korea showing UN and enemy dispositions on 30 May 1953.

US map of Korea showing UN and enemy dispositions on 30 May 1953.© National Army Museum, London

Highest military distinction

The Dutch detachment was integrated with French troops and due to the situation at the front, found themselves in the thick of the fight almost immediately. They would see a great deal of action in Korea for the rest of the war. The detachment distinguished itself during the fight to take hill 325 in Hoengsong from 12 to 15 February 1951. The Dutch were detailed to cover the retreat of the UN troops against the rapidly advancing Chinese troops. Communication with the South Korean division on their left flank was, however, so poor that the Koreans had not even informed the Dutch troops that they had retreated and abandoned their position. As the Chinese volunteers approached the Dutch lines, the Dutch troops mistakenly thought they were the South Korean troops in retreat! The Dutch were ambushed and their commander, Marinus Den Ouden, along with seventeen other Dutch soldiers, was killed in an attack on the command post. The battalion’s chaplain was also killed.

A dying Dutch soldier is assisted during the fighting on hill 975 in May 1951.

A dying Dutch soldier is assisted during the fighting on hill 975 in May 1951.© Netherlands Institute of Military History

The remaining Dutch forces were able to coordinate a retreat, but almost immediately got the order to counter-attack hill 325. Their first two attempts were thwarted but the third time, without ammunition and armed only with their bayonets, they managed to regain control of the hill. For their efforts, the soldiers received the Presidential Unit Citation for courage in the face of the enemy; the highest American military honour that can be bestowed on a foreign military unit.

The Belgian regiment came under fire on the Han River on 9 March 1951 and was deployed during the UN advance on the Imjin River. There, the Belgian troops were confronted with a Chinese counter-offensive. From April 20 to 23, the Belgians fought with the British against possible infiltrations by Chinese troops. They were just barely repulsed, despite having to regularly engage in hand-to-hand fighting. Ultimately, with the loss of thirteen soldiers, the Belgian detachment ensured that the rest of the brigade could safely retreat. For their heroism, this battalion was also awarded a Presidential Unit Citation.

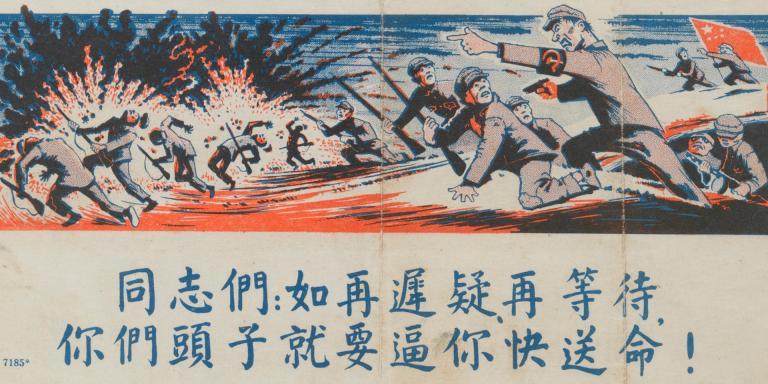

Propaganda leaflet encouraging Chinese troops to surrender, 1952.

Propaganda leaflet encouraging Chinese troops to surrender, 1952.© National Army Museum, London

Respect for the enemy

Noticeable in the veterans’ accounts are their respect and admiration for their Chinese enemies. One Dutch volunteer recounted the rumours that circulated about the cruelty of Chinese soldiers – and how servicemen were warned that they should avoid falling into Chinese hands. But a corporal from their unit who was wounded during the battle and left behind was, in fact, found alive the next day. The Chinese had moved him under cover.

In the eyes of these veterans, the enemies were seen as equals and not in terms of any pro- or anti-Communist stance. Another veteran who served from August 1951 praised Chinese soldiers who were courageous enough to attack using only the bayonets on their rifles, despite facing heavy artillery bombardments.

The Korean War ended with an armistice on 27 July 1953. It was then decided that there would be a demarcation line and a demilitarized zone between North and South Korea.

The Korean War ended with an armistice on 27 July 1953. It was then decided that there would be a demarcation line and a demilitarized zone between North and South Korea.© Flickr

The Korean front stagnated from April 1951. The Belgian and Dutch troops saw only sporadic action up until the signing of the peace treaty on 27 July 1953. Yet the UN mission to Korea undertaken by Belgium and the Netherlands remains one of the deadliest.

During the war, 107 Belgian and 123 Dutch soldiers lost their lives while 645 Dutch, and 478 Belgian soldiers were wounded. It was a cruel war that had no respect for the dead. That’s how the Belgian and Dutch veterans remember it. They don’t like to share their experiences because of the traumatic memories they still carry. They talk about corpses that lay for days along the side of the road because no one felt any need to recover them. The Korean War is often called “the forgotten war”. The Belgian Korea veteran René Tutteleers speaks of a ‘forgotten war and forgotten soldiers.’

Unprocessed traumas

The United Nations Korea Medal was awarded to all Allied military personnel.

The United Nations Korea Medal was awarded to all Allied military personnel.© Wikipedia

What is never described is how long the war continued in the psyches of those who fought there. Even after the war ended and the men were safely home, the war took the lives of countless Korea volunteers. Colonel Leendert Schreuders spoke poignantly about a night when the sergeant of a Dutch battalion standing guard duty suddenly saw a group of enemy soldiers approaching the frontline with a group of refugees. Unsure how to respond, the solider transmitted the information to Schreuders and asked what he should do. Schreuders ordered the sergeant to fire on the group because the troops would pose certain danger if they reached the Dutch lines. The enlisted man was taken aback by the order and informed the colonel that numerous women and children were mixed in amongst the enemy troops. But Scheuders was resolute and repeated his order to open fire.

A day later, the Dutch troops came across eighteen dead civilians, among whom were women and children. “I murdered them! I murdered them,” the sergeant wailed. The incident would cause psychological problems years later and eventually led the man to commit suicide. The sergeant simply could not come to terms with what he had done.

Treatment for and knowledge of post-traumatic stress did not exist in 1953. The trauma premium received by other soldiers was not given to the Korean War volunteers. Some carried their trauma with them throughout their lives as a kind of psychological ballast. That the war had repercussions on the lives of those involved was recently reflected in the decision of Korea veteran Willem de Buijzer, who asked to be buried in the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busan, Korea. He was buried amid his old comrades in arms who had lost their own lives 65 years earlier.

On 12 March 2019, the remains of Dutch Korean veteran Willem de Buijzer were buried at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busan, Korea.

On 12 March 2019, the remains of Dutch Korean veteran Willem de Buijzer were buried at the United Nations Memorial Cemetery in Busan, Korea.© defensie.nl