The Future of Historical Dutch Is International

Whether you are studying climate change in the seventeenth century or the native population of Brazil, if you have mastered historical Dutch, you will have access to a wealth of information. International interest in Dutch sources is huge and, thanks to digitalisation, there are more texts available than ever. But human know-how is lagging behind technological progress. The challenge is to maintain a level of expertise in historical Dutch. Not only within the language area, but beyond it as well, argues researcher Frans Blom, because Dutch-language heritage has a unique status among international scholars.

In June, with the temperature rising fast outside and the air conditioning blowing against a background of hooting taxis and sirens, I am at the annual Dutch Palaeography and Archives workshop at Columbia University. As a guest lecturer, I have the privilege, for one week, of showing eager PhD students their way around hand-written, Dutch texts from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. During the morning sessions, my colleague from Columbia deals with historical Dutch in printed texts, during the afternoons I deal with manuscripts.

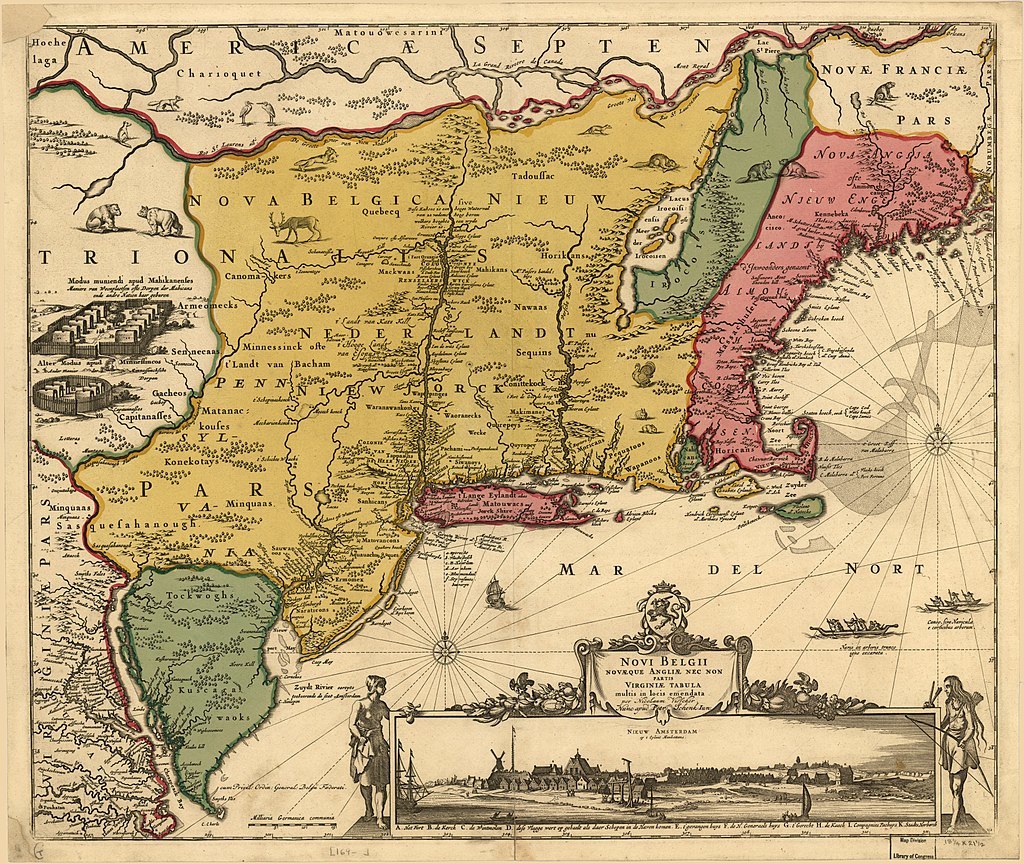

The interested participants have come to New York from all over the US, from Canada, and a few even from Asia, because they want to improve their Dutch and they want to learn the archival skills necessary for their art-historical or historical research. One is studying transatlantic trade, another wants to know more about the indigenous population of Brazil, someone else is doing climate change in the seventeenth century, others are doing research into Dutch painters and the art market, and there is always a group from the region, too, that is interested in the local history of Manhattan or in that of New Netherland, the first Dutch colony in North America.

Map of New Netherland and New England, and also parts of Virginia, printed in 1656

Map of New Netherland and New England, and also parts of Virginia, printed in 1656© Wikipedia

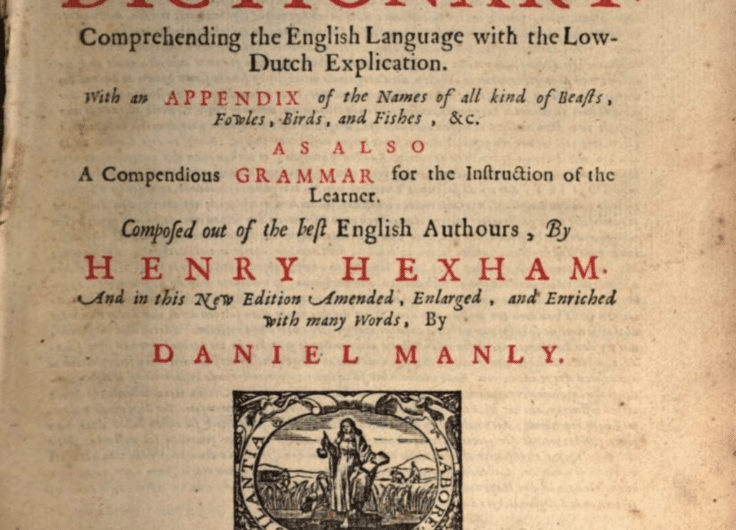

All week we study archive collections and read old prints and manuscripts. Monday, when we start, is always a difficult day. Everyone laughs nervously at the first sight of the old writing. We resort to palaeographical tools like Schriftspiegel and Het Nederlandse schrift, and we learn how, as non-Dutch-speakers, we can still do quite a lot with the online Dutch dictionary Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal. Tentatively, we get started with the writing and the language. Some have more aptitude for it than others. But by the end of the day, everyone has a headache. This could turn out to be a tough week.

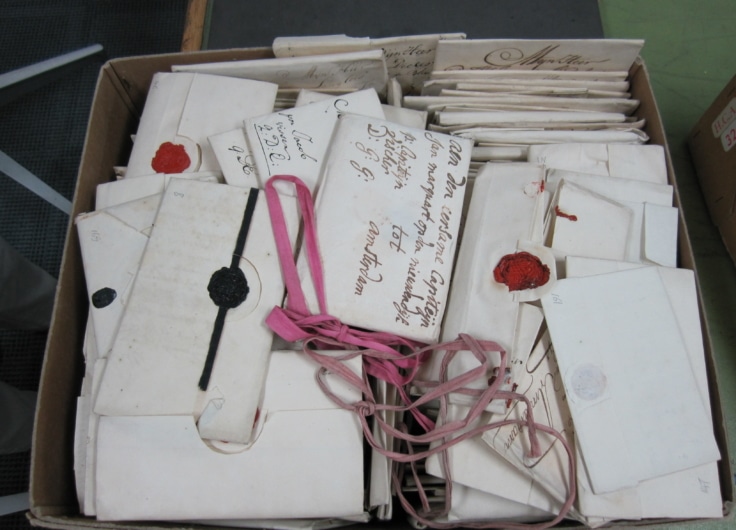

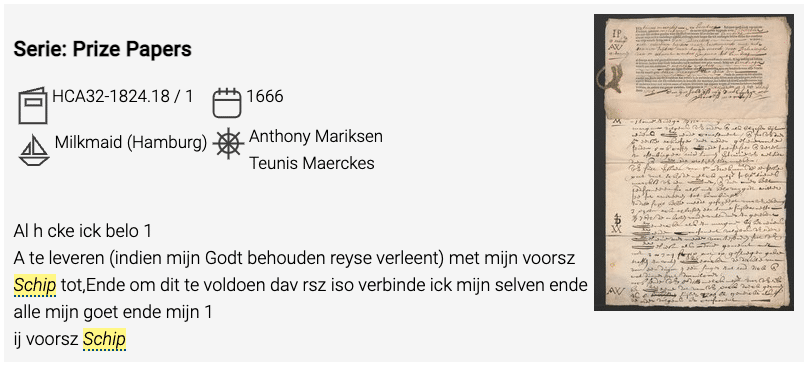

On Tuesday we do social history, using letters from the Prize Paper collection. By way of introduction, I tell how I once got boxes full of them served up at the British Archives in Kew Garden, how you unfolded these personal stories carefully, and how the voice of the letter-writer, which has long been discreetly sealed and locked away, suddenly speaks to you then. Together we read the beautiful handwriting of a mother in Amsterdam, who is worried about her son in the fleet and that he should stay away from bad people. The students especially like the ending, ‘May we see each other again with love till our salvation, amen. And I wish you a hundred thousand good nights’.

Thanks to letters captured by English privateers, historical linguists can investigate how ordinary people wrote in the Dutch Republic.

Thanks to letters captured by English privateers, historical linguists can investigate how ordinary people wrote in the Dutch Republic.© KNAW - Huygens Institute

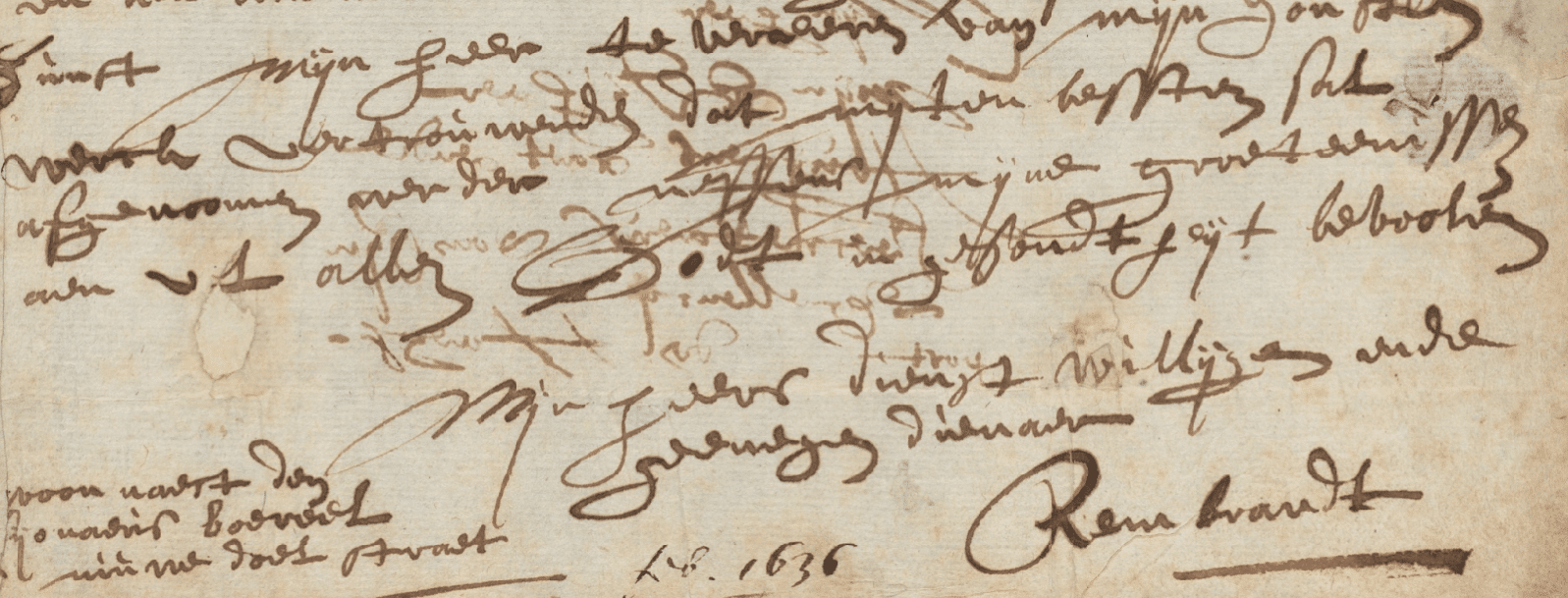

We dedicate the afternoon to Elsje Christiaens, a young woman from Jutland who was condemned to death for murdering her landlady, shortly after her arrival in Amsterdam. Rembrandt’s drawings of the slain girl, who had to hang on the Volewijck peninsula as bait for the birds, are well known among art historians. Now the drama hits us with full force as we read the hand-written trial documents with quotations from Elsje’s own defence. The doctoral students start shedding their reserve and, by the evening, as we raise a glass together to the Dutch language, everyone has.

Elsje Christiaens, drawn by Rembrandt

Elsje Christiaens, drawn by Rembrandt© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

On Wednesday we look at documents from the Dutch West India Company (WIC) and the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Thanks to the digitalisation projects that are underway in various places, we study documents from a number of collections. From the National Archives, there are eyewitness accounts of the volcanic eruption on the North Moluccan island of Ternate, in 1712. The text, in the clerk’s handwriting, can be read easily using François Valentijn’s somewhat later and slightly rewritten version in his book Oud en Nieuw Oost-Indiën (Old and New East Indies). We express thoughts on the variants in spelling, choice of words and sentence structure.

Later that day we open the digital Archives of the City of Amsterdam and study lists of ship’s cargo for the Amsterdam coloniers on what was then the Suyd Revier or South River, in New Netherland, and is now the Delaware: a sum of 150 guilders for a chest of medicines, 85 guilders for 50 pairs of clogs, 25 guilders for 30 pairs of assorted children’s socks and 4 reams of writing paper. Absolutely everything has a price tag in the seventeenth century.

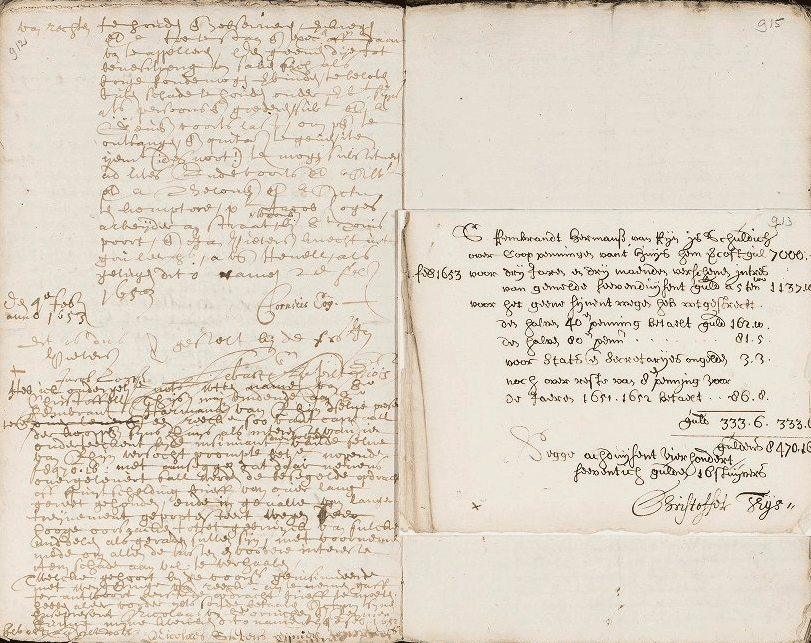

Thursday is the last day of the crash course, the PhD students are exhausted, but they want to continue. So, it’s time for painting. We visit Rembrandt. First, we study the inventory of his estate, made when he went bankrupt, as it appears online in the Getty Provenance Index. It is a much-quoted source, and yet the art historians are baffled by artistic jargon such as landschappie (landscape) and tronie (bust). Then we study the original manuscript of the inventory from the Amsterdam City Archives. As we read, we go step by step on a voyage of discovery through the rooms of Rembrandt’s house. Surprisingly, the manuscript indicates far more items than just the paintings that the Getty database lists. Rembrandt also surrounded himself with busts of Roman emperors, trinkets and exotic objects such as an East Indian powder box, an Indian cup, a Japanese helmet and a Moor cast to life. Finally, we come to the library and are amazed at the enormous quantity of art books Rembrandt possessed, and the print collections and drawings by the “greatest masters in the whole world”.

Statement of account of Rembrandt’s indebtedness to Christoffel Thijsz. for the purchase of his house (1 February 1653)

Statement of account of Rembrandt’s indebtedness to Christoffel Thijsz. for the purchase of his house (1 February 1653)© Amsterdam City Archives

Then it is irrevocably time, our foray into historical Dutch is over. We take the last group photo as a souvenir and as a ‘thank you’ to the Dutch Language Union, and then we go our separate ways in the clammy heat of the New York evening.

A wealth of internationally relevant information

Two things always strike me during the annual Dutch Palaeography and Archives workshops. The first is the unimaginable wealth of Dutch sources, and the infinite diversity of the past. The texts are so different in type, tone and content that even the most well-thought-out course on the subject is quickly bursting out of its seams. Yet fortunately, there is one thing that unites the copia et varietas, and that is precisely why the PhD students want this unique course: everything is recorded in the Dutch language. They know that those who master historical Dutch have access to a wealth of information.

The second thing that strikes me at Columbia University is the international relevance of Dutch sources. The texts reflect the global orientation and action radius of the Netherlands in the early modern period. They are significant not only for Dutch history but for the history of the whole world. That is evident from the origin of the students on the course, the texts that get them excited and certainly the subjects of the theses for which they need the sources.

Hardly any of them aspire to become specialists in the “history of our fatherland”, let alone the literary techniques of a canonical author like Vondel. Outside his own language area Constantijn Huygens, after whom many avenues, schools and institutes in the Netherlands are named, is not the great poet but the first witness of Rembrandt’s talent. And, conversely, much of Dutch-language heritage whose value is less obvious in the Netherlands has a unique status abroad. For many of the areas covered by the documents, there are no older written documents available. A Dutch-language source like the VOC report on the volcanic eruption on Ternate is instrumental in the local history and may provide answers to questions about the impact of natural disasters on societies in the Indonesian Archipelago. Such questions may have been formulated by a multitude of people and in various languages, but the answers are to be found in Dutch texts.

From the National Archives, there are eyewitness accounts of the volcanic eruption on the North Moluccan island of Ternate, in 1712.

From the National Archives, there are eyewitness accounts of the volcanic eruption on the North Moluccan island of Ternate, in 1712.© Wikipedia

Scanners on full speed

Thanks to digitalisation, Dutch-language sources are becoming increasingly visible. The Netherlands is one of the frontrunners, with the increasingly rich sites of the National Archives, special collections and many municipal archives. The scanners are running at full speed. Archives in other countries are also making more and more available online, and Dutch-language items from those collections are also appearing. The Prize Papers are a good example. Captured during the Anglo-Dutch wars, the overseas correspondence was stored as war information in the Tower of London, where the letters were lost from sight. For a long time, they were hidden away in boxes in the depot of the British Archives. Now that they are digitalised they are receiving attention again. An estimated forty thousand letters, written in Dutch during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, are available online via the site of the National Archives.

Fragment of the search website of Dutch Prize Papers

Fragment of the search website of Dutch Prize Papers© Dutch Prize Papers

Where a scarcity of sources was once a problem, today’s global digitalisation is producing an abundance. Google Books is happily digitalising old prints and Delpher is really impressive. International cooperation between the Royal Netherlands Library and collections at home and abroad has produced a digital collection of Dutch newspapers that ranges from the very first preserved copy by Broer Jansz, from 1618, to the large variety of papers from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Users can casually browse or search through it and may not even realise that substantial parts of these Dutch-language sources have been provided as scans by foreign archives, in Hamburg, Stockholm, London, St. Petersburg, Paramaribo, Cape Town or Jakarta.

We are inundated with manuscripts and old prints, absolutely everything, from perfectly legible to streaky. The trick now is to keep sight of what is important and not get lost in the details. Digitalisation helps with that too. Good search engines and interfaces not only work as signposts in the individual collections but, with the right infrastructure, they can also make queries in linked files. This rapidly diminishes the distance between collections and users. Search power is increasing. Furthermore, visitors’ hours are a thing of the past online. Where else in the world can you have the boxes served up on the screen in front of you, any time you want – like during the workshop on a Tuesday afternoon in New York, for example, when people in the Netherlands are already brushing their teeth. It all comes into view, totally clear, down to the tiniest details. Take a manuscript that is so difficult to read that it hurts your eyes, online you can zoom into it, enlarge it, rotate it and increase the contrast in a way that has never been possible in the reading room. And if historical sources are not yet available on the internet, they can be scanned to order.

Needle in a haystack

Digitalisation is a blessing for Dutch-language heritage and means nothing less than a second life for the fragile old prints and manuscripts. But the euphoria has its limits. The anecdote of Francesco Petrarch is famous. He sat in Italy, weeping over a manuscript of the Iliad that had just been brought from the Levant because he could not read Greek. That is what is happening now. The project to make all of William of Orange’s letters available online was revolutionary, but how many people can actually read or understand the correspondence of the Father of the Netherlands in sixteenth-century French, Latin and German? Digitalisation has made sources visible, and now it is time to get down to work.

There are tools for handwritten text recognition (HTR), like Transkribus, that focus on the automatic conversion of manuscripts into legible text files. That works well with the trained handwriting of, for example, VOC clerks. The ‘Unsilencing the VOC’ project uses HTR in its search for marginalised groups in historical sources. The NWO project Globalise goes a step further. It works with the ‘General Missives’ series from the archive collection ‘Letters and papers received’ from the VOC collection in the National Archives. It is an exceptionally large, rich corpus, estimated to consist of 105,000 folios, which provide a detailed account of events that took place in the region where the company was active during roughly the whole of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. (The dates vary somewhat, but just about everything between Japan, Cape Town and Yemen is included.)

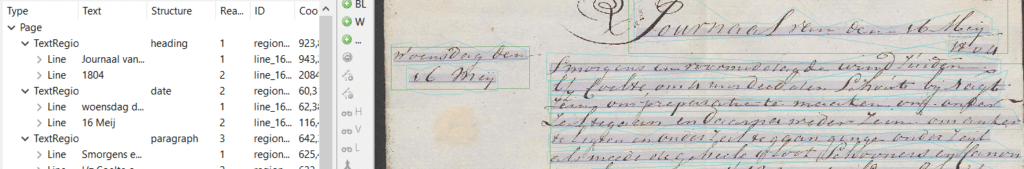

Tools like Transkribus focus on the automatic conversion of manuscripts into legible text files.

Tools like Transkribus focus on the automatic conversion of manuscripts into legible text files.Software is used to transcribe the manuscripts and to make an inventory of the geographical names, events and other entities. You can search the corpus for ‘Ternate’, for example, and find the day register concerning the volcanic eruption in the set of relevant hits. So, digitalisation not only helps increase the visibility of the sources, but also offers the necessary help in detecting the needles in the ever-larger haystack.

Expertise under pressure

In fact, though, the current state of affairs has barely advanced since the manuscript of the Iliad came into Petrarch’s hands – the real work has yet to start. In order to interpret the sources and assess their value for research purposes, knowledge of the historical language is needed. Increasingly that is lacking. Human know-how and skills in this area are not keeping up with those of the software but are lagging behind. For a great many reasons, the expertise that can be found in the Netherlands and Flanders and elsewhere in the world, is under pressure. Paradoxically, the space in the academic curriculum for transferring knowledge of historical Dutch and training new experts, is not increasing but decreasing, as more sources become available.

In international Dutch studies, much research is done based on Dutch-language sources, in the United States, for example, Indonesia, Korea and other countries in Asia, South Africa and the United Kingdom. (The Dutch Language Union is currently doing a survey and making an inventory and will publish the results.) But at the same time, the possibility of acquiring skills in historical Dutch abroad and using the historical sources for research is often even more limited. Students and researchers are dependent on extracurricular initiatives and workshops like the one in New York. These are intensive moments of knowledge transfer, but just as students start to learn something, they often find themselves on their own again. Then there are exercise modules, some lexical aids, like the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal, and for those who are not easily discouraged there are self-study methods, such as Mooijaert and Van der Wal’s Nederlands van Middeleeuwen tot Gouden Eeuw. Cursus Middelnederlands en Vroegnieuwnederlands (Dutch from the Middle Ages to the Golden Age. A course in Middle Dutch and Early New Dutch).

The handwriting of Rembrandt

The handwriting of Rembrandt© Harvard University

The increasing visibility of Dutch-language sources and their relevance for researchers abroad call for the development of facilities that maintain the expertise in the field of historical Dutch in the Netherlands and that support it beyond the borders of the Dutch language area. Internationalisation requires a new type of self-study method that takes into account that the target group are not native speakers of Dutch, that they attribute different values to Dutch-language heritage, and that they ask different questions of the sources.

The Dutch Language Union recognises that and supports the development of the self-study method Dutch for Reading Knowledge – Historical Dutch, by a team of Dutch and foreign academics. In the future, it may even be possible to use digitalisation not only to produce more content and develop more powerful software, but also to facilitate a community where people from anywhere in the world can find each other online with questions and answers: an English-speaking online Dutch Sources Community of researchers, students and others interested in historical Dutch-language source material, intended for consultation and advice, as well as for the tools to do independent research with Dutch-language archive documents. This type of digital infrastructure would not connect the different archives but those who use them.

As part of the online Dutch Language Union resources, Dutch Sources could bring together people in the Netherlands and abroad, support them and encourage them to endow Dutch-language sources all over the world with the value they merit.

With thanks to Karlijn Waterman from the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union) for the information about her research into the use of Dutch-language sources in international Dutch studies.

This article was realised with the support of the Dutch Language Union.