In the 14th century, the fractured mini-states of the Lowlands were being pulled apart by competing political and economic interests, warfare, dynastic struggles and the Black Death. The resulting instability meant that relations between the rulers and the ruled were constantly tested as the various layers of society tried to protect their interests in such perilous times. Whereas in Flanders this had led to bloody conflict between the count and the cities, in other parts of the Lowlands different methods were used to determine what this relationship should be.

At a magnificent ceremony in Brabant in 1356, a new duchess and duke signed a document that did exactly this, confirming certain rights of their subjects, including the right to disobey the ruler if they failed to uphold their end of the bargain. Although this so-called ‘Joyous Entry’ would be ignored almost from the moment of its signing, it would continue to have symbolic significance throughout the History of the Netherlands.

By the 1340s, the state of the Low Countries was thus. The Dampierre family were in power in Flanders and Namur; the Avesnes ruled in Holland, Zeeland and Hainault; Guelders and Zutphen were ruled by Reinoud of Wassenberg, who had just earned a promotion from count to duke, and also wrested control of the Oversticht for himself; Brabant and Limburg were controlled by the House of Reginar, a family line that stretched way back into the old Lotharingia days; Luxembourg was ruled by the House of Luxembourg; Liege and Utrecht were prince-bishoprics ruled by people who were almost always related to whichever other of these rulers had managed to get them places in those positions; Friesland, now minus West-Friesland, was as always just rocking along, doing its thing. All these rulers were playing a great game of 4D chess, with varying levels of success and failure.

The Rule of three Johns

Brabant was ruled by a bunch of Johns (in Dutch Jan). John I had taken over from his ‘infirm of body and mind’ brother, Henry IV in the 1260s. In the 1280s he had gone on campaign and managed to win control of Limburg. Brabant was not a vassal of the French king, and so had few qualms allying with those rebellious Flemish Dampierre counts, Guy and Robert of Bethune, against French incursion. John I married Margaret of Flanders.

The marriage of Margaret of Flanders to Duke John I of Brabant, depicted in a manuscript of the Brabantsche Yeesten.

The marriage of Margaret of Flanders to Duke John I of Brabant, depicted in a manuscript of the Brabantsche Yeesten.© Wikipedia

However, Brabant’s position within an anti-French coalition was cemented when the next John in line for dukedom, John II, was married to a different Margaret, the seventh daughter of the English king Edward I. John II took over from his father in the 1290s. He lived throughout the period of ridiculous instability in Flanders we have been covering; he would have, on many occasions, been awoken with news, or brought a hasty and concerned message, of yet another uprising, workers riots, street battle between weavers and fullers, capture of a noble lord by angry commoners, or defeat of an army of French knights by peasants holding pointy sticks, happening in the wealthy county to his west. Basically, John II had seen how the Flemish counts, whilst struggling for their independence against their French sovereign, had unsuccessfully dealt with the growing power of cities and their citizens trying to achieve their own version of freedom and independence.

Transitions of power were always periods vulnerable to instability and rebellion

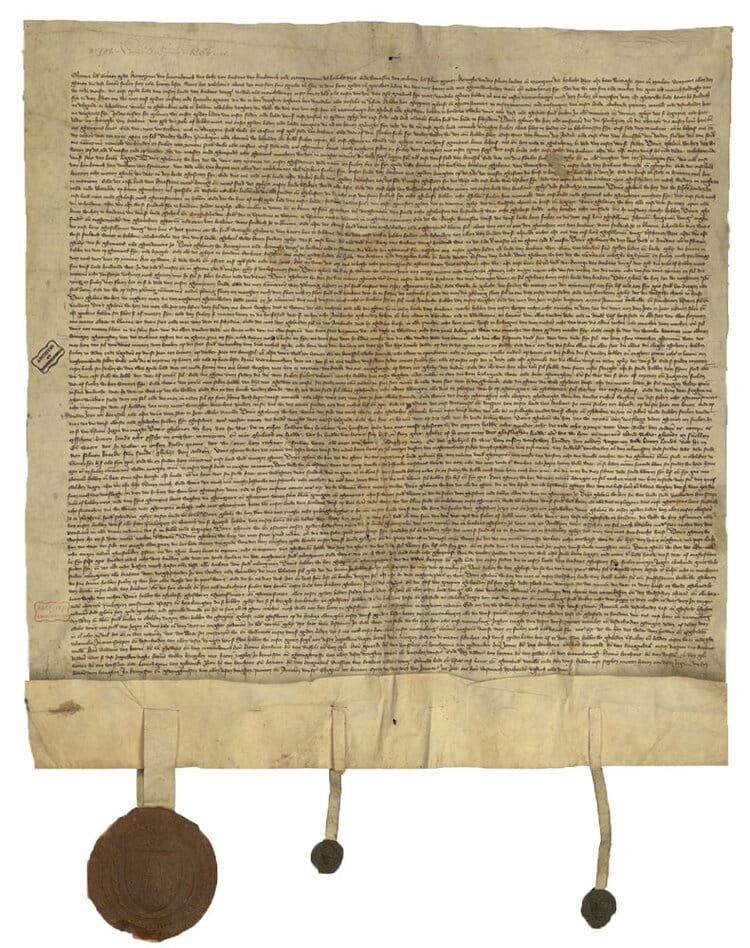

John II also had kidney stones and by the 1310s seems to have known that his time was almost up. His son, creatively also called John, was still young. Transitions of power were always periods vulnerable to instability and rebellion, as the vacuum of power would entice people from all levels to make a play to move up the ladder. John II knew that, following his death, if Brabant was to avoid the chaos that had torn Flanders asunder, he had to set a foundation by which the rule of his son would be respected by subjects who were progressively looking for greater rights and freedoms. The result was the Charter of Kortenberg. This is the first example in the Low Countries of anything resembling a constitution; pretty much the Magna Carta of the Netherlands.

The Charter of Kortenberg

The Charter of KortenbergSource: FelixArchief, Antwerp © Wikipedia

The Charter of Kortenberg

The Charter of Kortenberg put in writing that the Duke of Brabant would not be able to demand arbitrary taxes or levies on citizens except in a few exceptional circumstances, such as if he was taken captive and required ransom. It also said that all citizens, rich and poor, would be held to laws and judgements. Also interestingly, the charter created a council, and laid out how this so-called Council of Kortenberg was to be comprised: there would be four noble knights, three citizens from Leuven, three from Brussels, and one each from Antwerp, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, Tienen and Zoutleeuw. So of the 14 members, 10 of them were not from the nobility.

This is very different from Magna Carta, which only provided representation for barons. It required that the members of the Council take a Holy Oath to make sure they do their ultimate best to protect the public and uphold justice. The Council would meet every three weeks to make sure that the duke and his administrators were sticking to the agreements laid out. Most amazingly, it allowed for the citizens of Brabant to resist their duke or his descendants should the terms of the charter be broken by any of them.

Brabant is argued to be the first European state to give rights of participation in government to its social estates, including commoners

The Charter of Kortenberg is an extremely early example in Europe of the right for ordinary people to assemble, and be represented. That’s right, at the beginning of the awful 14th century, this is a remarkably progressive agreement between the ruler and the ruled. As such, Brabant is argued to be the first European state to give rights of participation in government to its social estates, including commoners.

Brabant, Flanders, England and France

John III ruled for over 40 years. Despite knowing that his interests lay in ongoing trade relations with England, he also faced enmity from all corners. Brabant’s dukes and Flander’s counts were in an ongoing dispute over the area around the town of Mechelen, which intensified when that town was made the staple for English wool. John was a cousin of the English king, but he was not afraid of flirting his loyalties with the French king. He even accepted a fiefdom and proclaimed himself a vassal of France. But the expansionist policies of the French king drove a wedge between Brabant and other lowlander territories, especially Holland, Zeeland, Hainault, the bishopric of Liege and Guelders. An alliance of these territories marched against him in 1334, but an agreement was negotiated by the French king. In these negotiations, John III lost parts of his realm to the Count of Guelders.

Map of the Southern Lowlands

Map of the Southern Lowlands© David Cenzer

So when his cousin, the English king, made a claim for the French crown and kicked off the Hundred Years War, John III switched allegiances. By now the Flemish towns were basically out of control, with Jacob Van Artevelde’s influence growing, so could not be counted on. John III supported Edward putting an embargo on Flanders and on the Flemish counts, and hopefully diverting all that cloth production to Brabant completely.

John III, Duke of Brabant

John III, Duke of Brabant© Wikipedia

John would agree to marry his second daughter, Margaret of Brabant, to the crown prince of England, who in Artvelde’s scheming was to become the inheritor of Flanders, the Black Prince. But alas, by 1340 Edward would be facing pressure to return to England, in addition to having run out of money. The Duke of Brabant was left alone to deal with the ramifications of the chaos erupting in Flanders on its border and deeply caught up in the family feuding going on across the Low Countries.

So given the English had just made a hasty exit from the continent, the marriage between Margaret of Brabant, daughter of John III, and the Black Prince never eventuated. Now talks between Brabant and France were once more entered into and, following an agreement signed in 1347, the two once again became allied. In this agreement, Margaret of Brabant’s marital fate was sealed, and she was betrothed beyond belief to the new Count of Flanders, Louis of Male.

Louis of Male, Count of Flanders

Louis’ father, Louis of Nevers, had been unable to curtail the Flemish towns. Louis of Male, however, largely succeeded in bringing Flanders back under his control following the fall of Van Artevelde at the hands of an angry mob in Ghent. His strategy was one of divide and conquer. When he faced the armies of Ghent and Bruges he promised them that he would give them back their privileges and pardon them. At that, Bruges went over to Louis’ side. Louis of Male seems to have been a better politician than his father ever was.

Ghent or Malines mint of Louis of Male

Ghent or Malines mint of Louis of Male© Wikipedia

He knew that Flanders needed English wool, so he agreed that his subjects could keep on recognising Edward as the king of France, as long as Edward himself would accept Louis’ rule in Flanders and his allegiance to Philip VI. By the end of 1349, Louis of Male was in control of all of Flanders again, though rebellious elements would remain in some of the towns, especially Ghent.

The Daughters of John III

John III, Duke of Brabant, had three daughters, and marrying them off tactically would be one of his main concerns. As we mentioned earlier, the middle one, Margaret, was married off to Louis of Male, in Flanders.

John made considerable marriages for his other daughters too. The eldest, Joanna, was wed to 15-years younger Wenceslaus of Bohemia, who was the Duke of Luxembourg, and the half brother of Charles IV of Luxembourg, the Holy Roman Emperor. The younger daughter Marie was married off to Reinoud III of Guelders. He was the Duke of Guelders, but he wasn’t the only one claiming the right to that position. Over the 1350s to 1370s the matter of succession to rule in Guelders became a hot conflict.

So by the time John III died in 1355, the rulers of Flanders, Guelders and the Holy Roman Emperor himself had direct vested interests in the matter of Brabant and its rule. John III planned for his eldest daughter, Joanna to succeed him. However, as John II had set a precedent for in 1312 with the Charter of Kortenberg, and because of new concessions made since by John III, the different estates in Brabant, the nobles, clergy and the city burghers, also had a direct say in the matter of who would succeed him. They agreed to Joanna, but as her husband was a foreigner who had grown up in Bohemia, around the modern-day Czech Republic, and was the half-brother of the Emperor, they required some assurance that the privileges and understandings of the relationship between the Brabant rulers and their subjects would continue to be adhered to.

The Joyous Entry

In 1356 Joanna and Wenceslaus came to Brabant to take the reigns of power. As they went from city to city, beginning in Leuven in January, they made what would become known fancily in French as la Joyeux Entree, in Dutch as de Blijde Inkomst and in English as the Joyous Entry.

The Joyous Entry was not just them making a frilled and feathered appearance to wave tidily at all their new subjects, but in the tradition of the Charter of Kortenberg, involved them putting their names to an agreement establishing assembly by the estates, controlling taxes, re-stating town privileges and agreeing that the lands of Brabant would remain indivisible. The Joyous Entry also ensured that if Joanna was to die without an heir, she would be succeeded by her ‘natural heirs’, meaning her sisters. This was a slap in the face to her new husband’s family, the House of Luxembourg-Bohemia. Similarly to the Charter of Kortenberg, Johanna and Wenceslaus also gave consent that they and their descendants could be resisted should they break any of the terms of the agreement.

“If we, our successor or our descendants should commit any act or cause any act to be done that contravenes these articles, points and stipulations, either as a whole or one of the parts, in any way whatsoever, we allow and stipulate that our good subjects mentioned before, no longer owe us, our successors or our descendants any service, nor obedience until such time as we have rectified the said act and completely renounced it.” – Final article of the Joyous Entry

The Joyous Entry of 1356 charter

The Joyous Entry of 1356 chartersource: Algemeen Rijksarchief, Charters van Brabant, nr. 901

The War of Brabant Succession

The Flemish Count, Louis of Male, married to Joanna’s younger sister Margaret, was looking at Brabant, and at the area around Mechelen, with its wool exchange, with very hungry eyes. In June of 1356, not six months after the first Joyous Entry of Joanna and Wenceslaus, Louis of Male made his own claim on the Duchy of Brabant by virtue of his wife, and backed up his claim with swords.

Duchess Joanna of Brabant and Duke Wenceslaus I, key players in the War of Brabant Succession.

Duchess Joanna of Brabant and Duke Wenceslaus I, key players in the War of Brabant Succession.Source: Adriaan van Baerland, Rerum gestarum a Brabantiae ducibus gestarum historia, 1526 © Wikimedia Commons

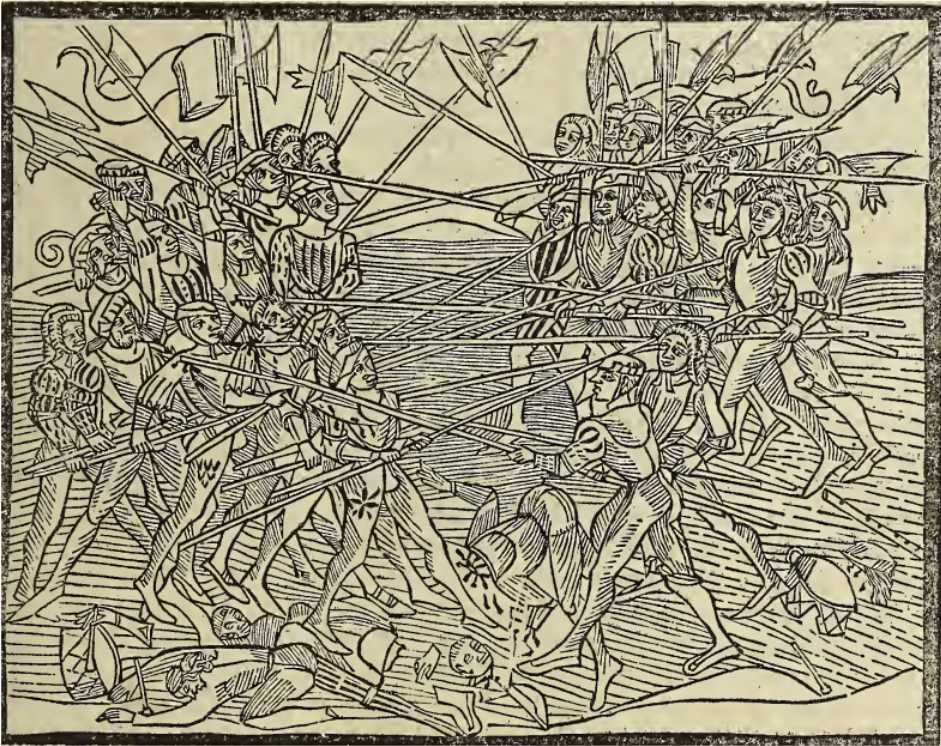

So began the war of Brabant Succession. Louis’ Flemish troops made quick gains over the course of two invasions in early August. He first landed about a thousand men to lay siege to Antwerp, blockading the city’s connection to the sea, with another flotilla ravaging the surrounding countryside. In a separate invasion, he sent a force south, heading for Brussels. Brabantine forces were positioned to halt them, but proved no more than a mere obstacle to be overcome. The Flemish army continued to scourge the countryside. Within sight of Brussels, they were met by another Brabantine army. This too was overcome, and as the survivors fled back towards Brussels, they were shocked to see that the people of Brussels had locked the town’s gates, out of fear that any Flemish would be amongst those seeking entry, forcing the survivors to continue fleeing. The next day Brussels surrendered and two days after that, Louis of Male made a triumphal entry into the city. By the end of August, Leuven and Antwerp also fell to the Flemish.

Joanna and Wenceslaus could only count two cities left in their domain, Maastricht and s’Hertogenbosch, which also happened to be the two most remote. Joanna holed up in lands that were her dowry, called Binche, while Wenceslaus had to flee and take stock of this mad chess move made by his new brother-in-law. Wenceslaus called in for some family support, going to his older half brother Charles IV, the Holy Roman Emperor.

With the Treaty of Maastricht, Charles agreed to back the cause of Joanna and Wenceslaus, as long as Brabant would remain in the Luxembourg-Bohemia line, directly contravening the terms laid out in the Joyous Entry. But, having the empire on her side was now something Joanna could brag about as she went around trying to eek back support from all the lords and towns that had surrendered to the Flemish. The tide began to turn in her favour.

Illustration of a medieval battle from the Cologne Chronicle.

Illustration of a medieval battle from the Cologne Chronicle.Source: Johan Koelhoff, Die Cronica van der hilliger Stat Coellen, 1499 © Wikimedia Commons

The news of imperial support also inspired some home-grown acts of patriotism, with the best-known example being in Brussels. A patrician of the city, Everard t’Serclaes, led a group of men-at-arms, scaled the city walls, brought down the Flemish flag flying above the town – a black lion on a gold background, and replaced it with the standard of Brabant which, confusingly, was a gold lion on a black background. Despite this, the town’s citizens were smart enough to tell the difference, and were encouraged by the gumption of Everard and his men. A popular uprising erupted, and the Flemish were driven from Brussels by the end of the next day. This allowed Johanna and Wenceslaus to make their Joyous Entry into that city in late 1356, where again they signed the document which they had already paid little heed to. Within just five days, all other Brabant towns had followed suit, and but for a small area called Malines, by the end of October 1356, Wenceslaus could happily tell his big brother Charles that the Duchy was back in their hands.

Everard 't Serclaes monument in Brussels. 't Serclaes made the Joyous Entry possible by retaking Brussels from the Flemings.

Everard 't Serclaes monument in Brussels. 't Serclaes made the Joyous Entry possible by retaking Brussels from the Flemings.© Wikipedia

But of course, this is not a case of ‘all’s well, that ends well.’ Louis of Male refused to concede, and so the Duke and Duchess of Brabant went about trying to diplomatically get themselves to some level of stability on this crazy chessboard. After trying their best at diplomatic wrangling, and having some of it fire back in their faces, they were left with little choice but to accept a mediated peace known as the Treaty of Ath, which greatly favoured Flanders. They agreed that Brabant lost Antwerp to Flanders, as part of the dowry of Louis of Male’s wife, the younger sister of Joanna.

Once again, the terms of the Joyous Entry were being stamped upon, since there were the lands of Brabant being divided. The centuries-old system of feudal acquisition and family or collateral inheritance would not just collapse with the flick of a quill on a piece of parchment. It became quickly clear that the Joyous Entry was to be more symbolic rather than something the rulers of Brabant or any other domain would actually have to adhere to. Nonetheless, for centuries it was something which any ascendant Duke of Brabant would have to swear upon when coming to power, and the ideal of it would hold importance for not only Brabant, but the Netherlands as a whole, going into the future.

Not only were Johanna and Wenceslaus going back on their word to the people, but by signing the Treaty of Ath they also went directly against one of the important stipulations of the Treaty of Maastricht, which they had agreed with the emperor just months earlier. What if the new duke and duchess did not have an heir? Then the titles for Brabant would pass to the next in line after Joanna, who was her younger sister Margaret, the wife of the Count of Flanders. The House of Luxembourg-Bohemia, the imperial family, were not at all happy about the thought of Brabant not going to them and this would remain a point of contention for years to come.

Louis of Male had proven himself to be quite a savvy operator, what with his pacification of his own rebellious subjects at home and his successful war abroad in Brabant

In the end, Louis of Male came out on top in the matters of Brabant. This Count of Flanders had proven himself to be quite a savvy operator, what with his pacification of his own rebellious subjects at home and his successful war abroad in Brabant bringing in new cities to his domains. But, as always, Flanders’ focus would remain on its entanglement between France and England. Whereas in the past Flemish counts had chosen to side with one of the great powers, much to the chagrin of the other, Louis decided to remain aloof and dangle a carrot in front of both of them, seeing which one wanted it the most. That carrot was a marriage with his daughter, Margaret of Flanders. As heir to Flanders, marriage to her would mean being able to rule Flanders in her name, creating a dynasty to continue doing that, and potentially also being in line for the inheritance of Brabant along the way. The weight of all that, plus the fact that this was the awful 14th century, meant that she was being shopped around from pretty much the day she was born. So who wanted her more, the French or the English?

The Marriage of Margaret of Flanders

Louis of Male’s daughter, Margaret, was first married to a French lord, Philip of Rouvres, Duke of Burgundy. These two were kids, one around 10 years old, the other about 5.

Philip of Rouvres isn’t important to us. In 1361 he died in one of two suggested ways, being the plague, or falling off his horse. Maybe he fell off the horse because he was vomiting plague induced blood. We don’t know. Anyway, his death without an heir meant that the lands of Burgundy, became ruled by the French crown. The King of France by this point was John II, and he gave the title of Duke of Burgundy to his youngest son, another Philip. Philip had a reputation already, having fought at the age of 14 at one of the great early battles of the Hundred Years War, the battle of Poitiers. There he and his father, the king, were captured and held prisoner for several years. For his supposed bravery throughout, he earned the nickname, ‘the Bold’.

Louis of Males once again had an opportunity to dangle his now eleven-year-old widowed daughter in front of the monarchs of France and England. Discussions were had to organise a marriage between Margaret and Edmund of Langley, the fourth son of English King Edward III. But Louis didn’t commit to anything because he wanted to wait and see whether he’d get a better offer from the French. Edward threw all sorts of extras in, such as Calais, and even potentially Holland and Hainault, which he had dubious claims to, but was vulnerable because it had fallen into a civil war which we’ll talk about in the next episode.

Philip the Bold of Burgundy and Margaret of Flanders

Philip the Bold of Burgundy and Margaret of FlandersSource: Antonius Sanderus, Flandria Illustrata, 1641 © Wikimedia Commons

Desperate to stop Flanders from falling to the hands of his arch-enemies, the new French King, Charles V, had the Pope in Avignon refuse to give his blessings to the marriage, because, get this, the two were too closely related. Louis of Male didn’t care, however, because within three years he had managed to get what he probably wanted all along. Charles V offered his younger brother, that Duke of Burgundy we mentioned, Philip the Bold. Out of this deal, Louis’ potential grandkids would be powerful French dukes. But even better for him, the deal included that he would be ceded back control of Walloon Flanders – those cities which we saw hacked off Flanders in 1305, Lille, Douai and Orchies.

So on the 19th of June, 1369, Margaret of Flanders and Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, were married in Ghent. This is a watershed moment for the History of the Netherlands. It would bring the Dukes of Burgundy onto the chessboard which everybody has been fighting over, and allow them to begin making moves of their own.

Sources

- Warfare in Medieval Brabant, 1356-1406, Sergio Boffa

- Magnanimous Dukes and Rising States: The Unification of the Burgundian Netherlands, 1380-1480, Robert Stein

- Hugo Grotius and the Century of Revolution, 1613-1718: Transnational, Marco Baducci

- Holland, Thomas Colley Grattan

- History of the Netherlands, John Lothrop Motley

- A History of the Low Countries, Paul Arblaster

- The Promised Lands, Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

- The political ranking and hierarchy of the towns in the late medieval duchy of Brabant, M. Damen

- ‘How one shall govern a city’: the polyphony of urban political thought in the fourteenth-century duchy of Brabant, Minne de Boodt

- Constitutions and their Application in the Netherlands during the Middle Ages by Raymond Van Uytven, Wim Blockmans

- De blijde inkomst van de hertogen van Brabant Johanna en Wenceslas, edited by Ria van Bragt

- The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt 1555-1590, Martin van Gelderen