On a visit to the university town of Leuven, Derek Blyth discovers one of Europe’s smartest cities, some of Belgium’s best bars and a walk that takes you to the edge of time.

It had to begin with a beer. I was in Leuven, the home of Stella Artois. I asked a friend where I should drink. Gambrinus, he said. It’s quiet. Civilised. You will like it.

Inside Gambrinus

Inside Gambrinus© Tripadvisor

And he was right. Gambrinus is a handsome bar on the Grote Markt decorated with wood panelling, gleaming copper chandeliers and faded murals. Typically Flemish, I was about to say. But then I noticed the Bavarian wall paintings and the inscription ‘Bürgerliches Brauhaus München’. It appears the original family owners were granted the exclusive right to sell beer brewed by the famous Munich beer house. And that was enough to save this café from destruction.

It was August 1914. The invading German army had just marched into Leuven. On 25 August, something happened that no one can properly explain. Some people say a sniper fired at the German troops. Or maybe a horse bolted. Whatever. It led to panic among the young German soldiers. A building caught fire. The flames spread. Within a few hours, most of this ancient Flemish city was burnt to the ground. More than 2,000 buildings were destroyed and 248 people died.

But Gambrinus was spared. The Germans apparently took care to save the one café in town that sold Munich beer. In 1932, the owners moved to a new location on the main square, where they carefully reconstructed the old interior. It is now owned by Stella Artois brewery. So you know what to order.

Great Market Square

Great Market Square© Tripadvisor

Looking out of Gambrinus, the main square looks pleasingly old. And yet it is almost all fake. Most of the old city was rebuilt in the 1920s. The money came from war reparations paid out by Germany. The locals chose to rebuild their houses in traditional Flemish style. You might be deceived into thinking the buildings around you are centuries old, until you notice that they are almost all decorated with a small stone tablet carved with the symbolic images of sword and fire, along with the date 1914.

Some people describe Leuven University, founded in 1425, as the Oxford of Belgium. The local population of 100,000 swells every September with the arrival of more than 50,000 students.

KU Leuven is the largest university in Belgium and the Low Countries.

KU Leuven is the largest university in Belgium and the Low Countries.© KU Leuven

But it isn’t Oxford. Not really. The ancient English university has survived intact, while Leuven has been torn apart by history. Many of the colleges were destroyed in the 1914 fire. Some never recovered, like Drieux College, founded by Michiel Drieux in 1559, of which nothing has survived apart from the Neoclassical entrance on Schrijnmakersstraat. The rest went up in flames.

The reconstruction has left Leuven with some mysterious buildings, including a strange row of eight houses hidden down a cobbled lane behind the Saint Gertrude Church. Known as the Thiéry Wing, the complex was built using bits and pieces of ancient buildings destroyed by the German army in 1914.

The eclectic Thiéry Wing of the Saint Gertrude Abbey

The eclectic Thiéry Wing of the Saint Gertrude Abbey© Marco Mertens

This strange example of postwar reconstruction was proposed by Armand Thiéry, a professor of theology who sat on the committee for the reconstruction of Leuven. He was quite a flamboyant figure, according to Wikipedia, where he is described as ‘a Belgian philosopher, theologian, professor, mathematician, lawyer, priest and architect.’

Thiéry bought the ruined Saint Gertrude Abbey with the aim of restoring the building. He then came up with the idea of using masonry salvaged from 16th and 17th-century houses to create a new wing. The result is an eclectic jumble of Baroque doorways, Renaissance sculpture and modern details.

I was beginning to understand that things had not always worked out in Leuven. In the 13th century, the city was part of the wealthy Duchy of Brabant, as was Brussels. Leuven might have become the capital of Brabant, the capital of Belgium, perhaps even the capital of Europe. But the Dukes of Brabant preferred to settle on the heights above Brussels.

Maybe Brussels was a better choice. Leuven stands in a boggy area where it is difficult to build anything higher than three floors. The architect of the City Hall had to abandon a plan to add a belfry as the ground was too marshy to support it.

Saint Peter's Church

Saint Peter's Church© Leuven by air

The church opposite was another architectural failure. The original plan involved three spires built against the west front, including a central spire that would have been the tallest in the world. You can admire a model inside the church. But the project had to be abandoned because of the marshy location, leaving just the foundations

The ornate 15th-century City Hall

The ornate 15th-century City Hall© David Degelin

The fire in 1914 added to Leuven’s woes. Hardly anything survived apart from the Stadhuis (City Hall). The German army had set up its headquarters inside the ornate 15th-century City Hall, which meant it survived without a scratch.

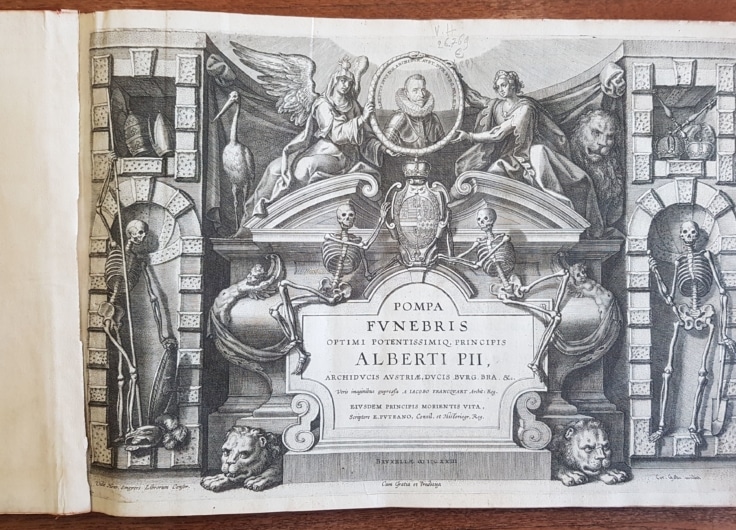

Erasmus

Erasmus© Visit Leuven

The façade is decorated with more than 200 Gothic niches that were originally intended to hold statues. But the money ran out and the niches remained empty until 1852. A plan was launched, and fiercely debated, to fill the empty spaces with figures from Leuven’s history. You might spot Erasmus up there, along with various professors. But the 200-kilo figure representing King Leopold II was taken down in 2020 following Black Lives Matter protests.

After six centuries, the city officials finally left the building in 2008. They now work in a smart new city hall next to the station. The old Stadhuis is to be restored over the coming six years by the architect firms aNNo and Felt. Meanwhile, citizens are being asked for their ideas on using the empty building. You can follow the discussions in the Atelier Stadhuis exhibition space next to the tourist office.

Tomb of Henry I, Duke of Brabant in the Saint Peter's Church

Tomb of Henry I, Duke of Brabant in the Saint Peter's Church© Visit Leuven

On the other side of the square, an ambitious renovation of the Saint Peter’s Church finally ended in 2020, after 35 years of construction work. The ornate Brabant Gothic interior has been stripped back to its original cool white stone and all the religious clutter removed, leaving just a small collection of paintings and sculptures in their original settings, including Dirk Bouts’ ‘Last Supper’ and the tomb of Henry I, Duke of Brabant.

The church has worked with Museum M to create a setting that is like a contemporary museum. You can visit for free, or pay for an iPad to find out more about the collection. Or rent a slightly scary HoloLens headset equipped with smart glasses to view the paintings in 3D.

'The Last Supper' by Dieric Bouts (ca. 1410-1475)

'The Last Supper' by Dieric Bouts (ca. 1410-1475)© Visit Leuven

*

I was spending the night in a hotel that occupied a renovated Gothic building opposite the church. It was called The Fourth. I was curious about the name. What happened to The First? And the other two?

The building was originally constructed in 1479 for the local guilds. It became a theatre in 1817, a branch of the National Bank in 1930 and finally, in its fourth role, a cool boutique hotel where bedrooms have smart light switches and a personal supply of artisanal coffee beans from Bolivia.

I set off the next morning to look at the university library. The Third, you might want to call it. The first library moved in the late 17th century into the mediaeval cloth hall, adding a mismatched baroque upper floor to the original Gothic building. Then came the 1914 fire, which gutted the building and destroyed its collection of 300,000 books and rare manuscripts. Just 30 charred volumes survived the scorching heat, each one now displayed in a separate glass case like a religious relic.

The second library was constructed using money raised by a consortium of countries led by the United States. The new building was designed by the American architect Whitney Warren in a style inspired by Flemish renaissance and baroque buildings. It even has a Flemish belfry. You can wander through the arcade to read the plaques that list in elegant calligraphy the American universities that paid for the reconstruction in the 1920s.

The (third) University library

The (third) University library© Layla Aerts

But the Germans weren’t done with Leuven. They returned in 1940 and set fire to the library once again. It was rebuilt for the third (and hopefully last) time after the war. But the solemn institution was shaken by a linguistic conflict in the 1960s when students campaigned to turn Leuven into a Flemish institution with classes taught in Dutch rather than French. The demonstrations rumbled on for several years until the French-speaking students were finally moved out to a new campus at Louvain-la-Neuve.

The books in the library had to be split between the two universities. But how do you divide a set of dictionaries, or a collection of periodicals? The solution was quite surreal – volumes with an odd shelf number stayed in Leuven while those with an even number went to the new university. It meant, a glum Belgian librarian once explained to me, that Leuven owned half the volumes of an encyclopaedia, while the other half was down in Wallonia.

Inside the university library

Inside the university library© Rob Stevens

The first library is still standing on Naamsestraat. It is a strange, battered building occupied by administrative offices. You can go inside to look at the impressive Gothic hall where the cloth was sold in the Middle Ages. The vast vaulted space is now occupied by a coffee bar and university shop.

The first university library houses a coffee bar and university shop.

The first university library houses a coffee bar and university shop.© Visit Leuven

I spent an hour or so strolling around the colleges on Naamsestraat. The Heilige Geest College, founded in 1442, is the oldest, although nothing has survived of the original building. The Van Dale College, founded in 1569, looks more the part of an ancient college with its handsome renaissance courtyard, old water pump and mellow red brick walls.

The Van Dale College

The Van Dale College© KULeuven / Rob Stevens

A hidden gate behind the college leads to a wild trail known as the Dijlewolvenpad. The meandering path descends through a nature reserve to the valley of the River Dijle. A short walk brings you to another secret spot known as the Dijlepark. Once a private garden, this little landscaped park enclosed by two sluggish branches of the Dijle strikes a romantic note with its iron bridge and gazebo.

Dijlepark

Dijlepark© City of Leuven

A detour took me to a little park next to the river laid out on the site of a car park. From here I could see two ancient round towers on the banks of the Dijle that had been hidden for centuries. Originally built in the 12th century as part of the city defences, they were abandoned when Leuven expanded around 1360.

One tower became known as the Janseniustoren after the Dutch theologian Jansenius renovated it in 1618 and lived there for eight years. The other one, currently surrounded by scaffolding, is known as the Justus Lipsiustoren.

Aerial image of the Justus Lipsius tower and Jansenius tower

Aerial image of the Justus Lipsius tower and Jansenius tower© Erard Swannet

I ended the walk in the beautiful Begijnhof (Beguinage) on the edge of the old town. Once a walled mediaeval community of single women, it is like a separate little town, with bumpy cobblestone lanes, mellow brick houses and little bridges across the Dijle. The houses have been carefully restored to provide accommodation for international students and professors, who have the good luck to live in a setting that looks like a mediaeval Flemish painting.

*

On the other side of Leuven, I discovered an old gate that led up the Keizersberg, or Emperor’s Hill. A castle once stood on this site, but nothing remains except a well and a ruined wall. The site is now occupied by a gloomy 19th-century Benedictine abbey, along with some mysterious ruins, a hidden cemetery and an orchard planted with rare apple trees. Standing on the summit, I got a view of the old spires as well as the sprawling Stella Artois brewery.

And that reminded me. As well as educating students, Leuven has been a brewing city since the Middle Ages. The famous Stella Artois brewery traces its origins back to an inn called Den Hoorn (The Horn) where local hunters would stop for a drink. It had a brewery attached that was entered in the Leuven city records back in 1366.

Historic brewing hall Den Hoorn

Historic brewing hall Den Hoorn© Visit Leuven

The Den Hoorn brewery grew rapidly after the city gained a university. It changed its name to Artois in 1717 after Sébastien Artois took over. The name Stella (star) was added when the beer was launched in 1926 as a limited-edition Christmas drink. And it put the date 1366 on the label to prove it had been around for a long time.

When Stella Artois was launched in the United Kingdom in 1976, it was branded a ‘premium lager’ and served in its own distinctive glass. ‘Reassuringly expensive,’ the slogan defiantly claimed. The beer was marketed in a series of lavish adverts modelled on new wave French movies, so everyone thought the beer from Leuven was a sophisticated French drink that might fit in well with an evening at an arty cinema watching something by Jean-Luc Godard.

The company tried in 2010 to persuade local people in Leuven that Stella was a premium lager. But no one was fooled. It was an ordinary Belgian beer to drink in a local bar. Reassuringly affordable, you might want to say.

Stella Artois brewery

Stella Artois brewery© AB InBev

Overlooking the Leuvense Vaart canal, Stella Artois has grown into one of the largest breweries in the world. Now part of the multinational AB InBev, the company produces two million litres of beer a day in a modern plant. Meanwhile, the former brewery site is being turned into a hip neighbourhood with c, including a stylish bar called De Hoorn where you can drink a cold Stella straight from the tank.

I have no idea how many bars there are in Leuven. It is a lot. Many are located on the Oude Markt (Old Market Square). They call it the biggest bar in the world.

The Old Market Square, home of many bars and students

The Old Market Square, home of many bars and students© Erard Swannet

But the interesting bars are probably not here. I liked the look of Leuven Central, where the owners have restored an abandoned volkscafé. Located near a plaque that marks the city’s official centre, Leuven Central still has its original interior with wooden furniture, Stella Artois signs and rows of aspidistras on the window sills. It offers authentic Flemish bar food, like pistolets met hesp (ham rolls), homemade meatballs and even a basket of hard-boiled eggs sitting on the counter.

Then there is the striking modern café Entrepot located in a renovated industrial building opposite the Stella Artois brewery on Leuven’s Vaartkom waterfront. It has a rough industrial interior with recycled wooden tables, iron pipes and a suspended silver sculpture by Pieter Jansen. Its waterfront terrace is the perfect spot to drink a chilled Hoegaarden beer (an InBev brand).

But Leuven is not just about beer. The city has serious coffee bars where students sit with a Flat White and a textbook. The tiny Mok has been roasting its own coffee in the heart of Leuven since 2012. Or you can head to Madmum on the Vaartkom where they roast their coffee in a big industrial space facing the old Stella factory.

Leuven is not just about beer. The city has serious coffee bars where students sit with a Flat White and a textbook.

Leuven is not just about beer. The city has serious coffee bars where students sit with a Flat White and a textbook.© Karl Bruninx

The city is also a good place to go shopping in independent stores. The appealing Mechelsestraat has an eclectic range of unique stores, among them a pharmacy, Italian deli, cheese shop, toy shop and a specialised shop dedicated to taxidermy.

And of course, there are the bookshops, like beautiful Barboek hidden down a quiet cobbled lane. Located in a former printing works, it displays books in several intimate rooms furnished with round tables, armchairs and sofas. You can sit among the books with a coffee or outside in the little courtyard when the weather is fine.

*

‘You need to listen to Het is weer druk in Leuven – it’s busy again in Leuven – by the band Noordkaap,’ a former student told me. ‘It’s about going back to university.’

‘Students standing in the street/ They are laughing, strolling and showing off/They know what studying is all about,’ the song begins. But then the lyrics turn darker. ‘I’m alone again in Leuven/I ask myself, what am I doing here?’

The students start to arrive in September. They pedal around on bikes and cram into the bars on Oude Markt. But they don’t stay all the time in Leuven. On Friday afternoons, most students like to take the train back home. So Thursday is the night to go out drinking, while weekends are rather quiet. Once again, not really like Oxford.

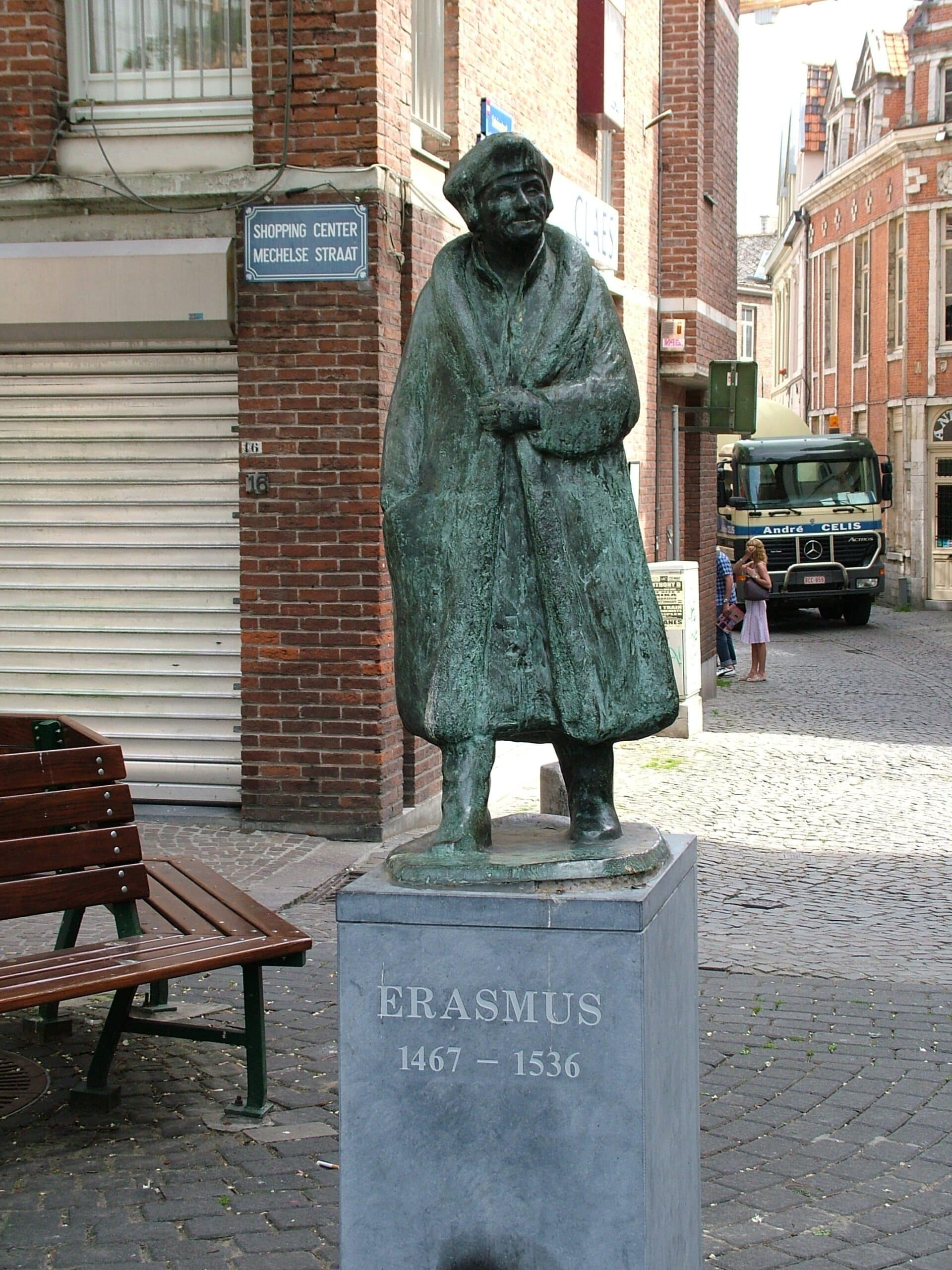

The humanist Erasmus spent some time in Leuven.

The humanist Erasmus spent some time in Leuven.© Visit Leuven

Leuven likes to call itself a smart city. It has been an important centre of learning for six centuries. The first edition of Thomas More’s Utopia was produced on a Leuven printing press. The humanist Erasmus spent some time here. He is commemorated by a bronze statue in Mechelsestraat, often buried under a stack of bicycles, and by the romantic, overgrown Erasmustuin sculpture garden next to the Faculty of Literature. So yes. Leuven is a smart city (even if you can only find half the encyclopaedia).

Many of the university colleges were originally Catholic institutions, training students to work as priests or missionaries. One of the university’s most famous students lies buried in the crypt of a mediaeval pilgrimage chapel near the Begijnhof (Beguinage). In 1873, Jozef De Veuster, better known as Father Damien (or Damiaan in Dutch) travelled as a missionary to Hawaii to work in a leper colony. Tragically, he caught the incurable disease and died on the island in 1889.

Father Damien lies buried in the crypt of Saint Anthony's Chapel near the Beguinage.

Father Damien lies buried in the crypt of Saint Anthony's Chapel near the Beguinage.© Wikipedia

Damien was eventually declared a Catholic saint. In a poll, he was voted the greatest Belgian of all time. There is a statue in Tremelo, his hometown, and a copy in Washington’s Capitol building, of all places. He was selected for this honour by the state of Hawaii, when it was asked to nominate a figure.

The Belgian saint’s reputation took a knock recently when the Democrat representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez criticised him as representing ‘patriarchy and white supremacist culture.’ But the Damien expert Ruben Boon defended the priest who was, he argued, ‘much more Hawaiian than Belgian, white or whatever.’

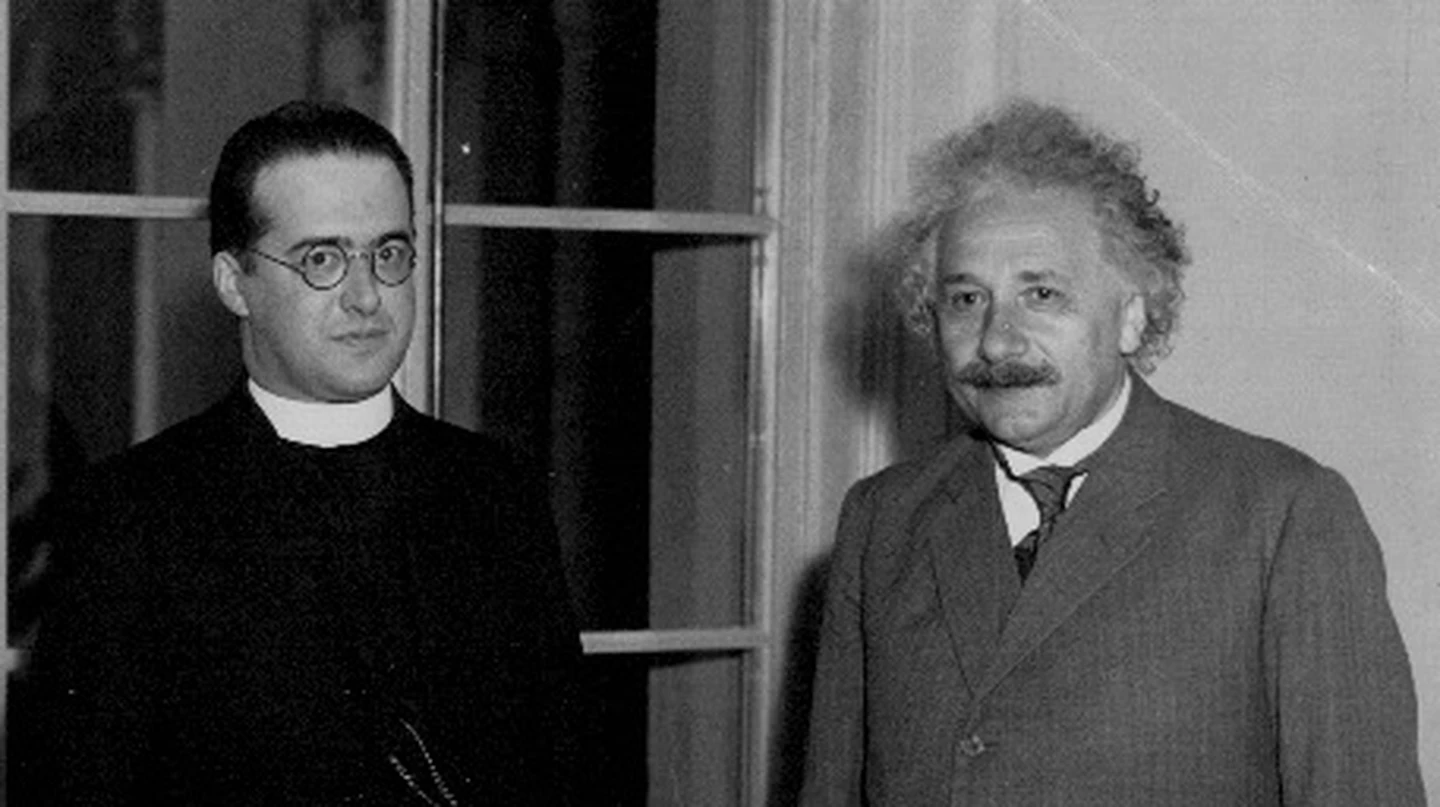

Damien is not the only famous priest from Leuven. Georges Lemaître was a devout Catholic who taught at Leuven university. No one took any notice of him as he sat in Leuven’s Heilige Geest College working on a complex scientific theory that would explain the origin of the universe. Publishing his results in 1931, he called it the Primeval Atom Hypothesis, although it is better known as the Big Bang Theory. Albert Einstein initially rejected the idea when it was proposed. Then he changed his mind.

Priest Georges Lemaître, the man behind the Big Bang Theory, with Albert Einstein

Priest Georges Lemaître, the man behind the Big Bang Theory, with Albert Einstein© thirdwise/Flickr.com

The city recently came up with an imaginative way to recognise Lemaître’s bold idea on the origin of the universe, 13.77 billion years back in time. It commissioned the French artist Félicie d’Estienne d’Orves to create an urban artwork titled Primeval Atom. She realised it was quite difficult to conceive a time scale of 13.77 billion years. Hard enough to grasp the 600 years that separate us from the construction of the Leuven City Hall. Her idea was to create a two-kilometre urban walk

that would represent a journey to the beginning of time.

French artist Félicie d’Estienne d’Orves created an urban walk that represents a journey to the beginning of time.

French artist Félicie d’Estienne d’Orves created an urban walk that represents a journey to the beginning of time.© Marco Mertens

The idea is simple. The artist has placed 80 tiny brass medallions in the cobblestone streets across the city to represent the important galaxies. Some have quirky nicknames like Mirach’s Ghost and Black Eye Galaxy. Others are just numbers.

You begin on Rector De Somerplein where a light circle in the pavement stands for present time. And off you walk, back in time, one step representing roughly 10 million years.

The route leads eventually to a spot in the middle of the city ring road that is close to the beginning of time and space. Well, to be honest, not that close. It is still 429 million years from the Big Bang, which happened somewhere out in the suburbs, if that makes any sense.

Félicie d’Estienne d’Orves shows one of 80 medallions that represent a galaxy.

Félicie d’Estienne d’Orves shows one of 80 medallions that represent a galaxy.© Marco Mertens

The James Watt Telescope recently sent back dramatic images that capture the universe as it was 13 billion years ago. Not far off the moment that we call the Big Bang, because of a quiet priest from Leuven.

The smart city of Leuven isn’t just interested in brain power. The city council wants to use digital data to make Leuven a better place to visit. For the past 15 years, it has been tracking the movement of visitors using smartphone data. The aim is to find out who goes where. For example, how many German tourists climb the library tower? How many people come from Brussels to do shopping? Cunning stuff like that. I would love to be told how many people, like me, have stood in the middle of the ring road, trying to figure out what it means to be 429 million years from the beginning of time.

Museum M Leuven

Museum M Leuven© Robin Van Acker

I found more evidence of smart thinking in the city museum. This was once a creaky cabinet of curiosities known as Museum Vander Kelen-Mertens. It is now called M. Simple as that. In 2010, architect Stéphane Beel brilliantly transformed the museum and the former city library next door into a stunning contemporary art venue. The building incorporates a kids’ area, café and rooftop terrace. The curators put on interesting temporary exhibitions as well as displaying paintings and religious sculptures in a series of intriguing spaces where modern works are hung next to Old Masters.

Leuven’s cultural centre STUK is another smart spot. Founded in the 1970s as an experimental arts centre, it is now a vibrant art venue. Located in a renovated neo-gothic building on a steep slope that runs down from Naamsestraat, it’s a bustling place to catch contemporary theatre, dance and jazz, or just to drop in for a coffee. (It reopens in October 2022 after a major renovation).

In 2005 Leuven decided to bundle five cultural venues together under a single name. So they became known as 30CC because someone argued at the time, it sounded ‘snappy and modern’ but also like ‘the engine of a clapped-out motorbike’. The clapped-out motorbike now organises theatre, dance, book readings and music performances in several venues across the city, including the grand city theatre.

The city mayor Mohamed Ridouani encourages Leuven’s citizens to do some smart thinking for themselves by lending his support to urbanism and sustainability ideas, including the ‘and&’ festival of innovation (held every two years) and the MindGate community.

His plan has helped to make Leuven into a dynamic and optimistic city of the future. It was chosen as the European capital of innovation in 2020, earning praise for an inspiring governance model that encourages the public to innovate. The city has also been selected as one of 100 EU cities that pledged to reduce their carbon footprint to zero by the end of the decade.

*

The university city sits in a valley with gently rolling hills to the east. I picked up a bike to roam around. It doesn’t take more than five minutes to get out of the city on quiet cycle routes. The neat rural landscape is dotted with old abbeys, farmhouses and even some vineyards.

The route I had planned took me out to the Abdij van Park on the edge of the city. Its baroque tower rises above fields with grazing cattle. It even smells of manure in the abbey’s cobbled courtyard.

Abdij van Park

Abdij van Park© Cédric Verhelst

The abbey was founded back in 1129, although most of the buildings now standing date from the 17th century. It belongs to the Norbertine order (also known as the Premonstratensians). The sprawling complex – which is still occupied by a few Premonstratensians – is now being restored. It is an enormous project that will only end in 2025, but you can already visit a large part of the complex where a museum of religious art called Parcum opened in 2021.

It is a stunning experience. You enter through a cool cloister lined with 17th-century stained glass windows that tell the story of St Norbert. The windows were sold in the 19th century when the abbey was short of funds, and ended up scattered across the world. But researchers managed to track down many of the windows and return them to the abbey.

17th-century stained glass windows tell the story of St Norbert.

17th-century stained glass windows tell the story of St Norbert.© Wouter Jaspers

As you walk around, you come across the abbey’s motto, Ne quid nimis, ‘Nothing in excess’. But when you enter the refectory, you realise the fathers didn’t take the motto too seriously. The ceiling is decorated with extraordinary stucco scenes by Jan Christiaan Hansche illustrating scenes from the Bible, all involving food. The Last Supper, of course, is up there, along with an intimate portrait of Martha and Mary in a kitchen.

the refectory of the abbey

the refectory of the abbey© Wouter Jaspers

And there is more to come in the library. You enter a dark room lined with bookcases and another beautiful stucco ceiling above your head illustrated with biblical scenes linked to books. The three-dimensional stucco figures emerge from the ceiling like a 17th-century version of HoloLens glasses.

the library of the abbey

the library of the abbey© Cédric Verhelst

The tour continues through the Abbot’s residence and his private chapel. The rooms decorated in a gilded baroque style seem to suggest that the slogan ‘Nothing in excess’ has become ‘Everything in excess’.

Humanist Hieronymus Busleyden, founder of the Collegium Trilingue

Humanist Hieronymus Busleyden, founder of the Collegium Trilingue© Wikipedia

Back in Leuven, there was one last place I needed to see. The Collegium Trilingue

was founded by the humanist Hieronymus Busleyden in 1517. Inspired by Erasmus, it was the first college in the world to teach students in Latin, Greek and Hebrew. It attracted some of the finest scholars of the age, such as Justus Lipsius and Andreas Vesalius, and established Leuven as a centre of renaissance learning.

If the smart city began anywhere, it was the Collegium Trilingue, I decided. But I couldn’t find the building. Not even Google could locate it. Finally, I spotted a narrow alley called Busleydengang on Vismarkt square. It led to a deserted courtyard with a few parked bicycles. No sign. Nothing to mark the site of Erasmus’ dream.

Never mind, there’s always beer, I thought, and headed back to a bar on the Vismarkt with the hopeful name Optimist.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.