The Making Of: Orestes in Ghent and Mosul

A vicious circle of revenge and retaliation, seemingly impossible to break; that is just one of the significant parallels we can draw between Aeschylus’ Oresteia and the current state of affairs in Northern Iraq, on the front lines with ISIS. The Swiss director Milo Rau united those elements, both literally and figuratively, by heading to Iraq with his cast and crew. The video footage they shot there was then integrated in Rau’s most recent production for Ghent city theatre NTGent. Ons Erfdeel’s editor-in-chief Luc Devoldere headed to the theatre and left the performance with mixed feelings.

Do you remember The Oresteia, the story about Orestes? In this trilogy, which was first performed in Athens in 458 BC, Aeschylus immortalised the origins of the rule of law and the justice of the state, i.e. how to transform chaos into order, how to break the cycle of violence, and turn clans into a community.

Clytemnestra hesitates before killing the sleeping Agamemnon, painting by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, 1817

Clytemnestra hesitates before killing the sleeping Agamemnon, painting by Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, 1817© Musée du Louvre

Clytemnestra kills her husband Agamemnon, the Trojan War’s victorious hero, because he had sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia in order for the winds to return so his fleet could sail to Troy. Her son Orestes is forced to exact vengeance after his father’s death, and kills both his mother and her lover. Consequently, Orestes is the target of the Furies’ wrath. He has no choice but to flee to Delphi where he is granted sanctuary in Apollo’s temple. The Furies set up camp outside the temple walls. Deadlock. In the end, a trial is set up in Athens. Orestes appears in front of the Areopagus, and the goddess Athena supervises the court. The Furies, or ‘Erinyes’, take on the prosecutor role. Apollo acts as Orestes’ defence attorney. Once indictment and plea are over, votes are cast. Voting comes to an end. Athena casts the deciding vote and Orestes is absolved. By way of compensation, the Furies are granted asylum as well as a cult in Athens: the Erinyes metamorphose into the ‘Eumenides’, or the ‘Kindly Ones’.

Orestes pursued by the Furies, painting by Adolphe Bouguereau (1862)

Orestes pursued by the Furies, painting by Adolphe Bouguereau (1862)© Chrysler Museum of Art

Curtain

I had seen this trilogy with a happy end before, in Rotterdam in 1994, directed by Peter Stein. In Russian. The three-parter’s main issue is its denouement. How can we depict gods on stage? With a little help from the irony pulley? It all started with the so-called dea ex machina Athena, who Stein had land on stage like some kind of elegant trapeze artist slash paratrooper. Both she and Apollo behaved in a frivolous, light-hearted and arrogant way. At first, the trial appeared to be a charade. As if Stein wanted to show his audience that the rule of law, democracy, is always frivolous, as it is hustling and hoodwinking, yet at the same time is the only one who is able to put a stop to violence through compromising.

At the end, Apollo wrapped the Furies in crimson bindings – as well as around his little finger. Even though the Furies were all bundled up, they were allowed some space. They were sent packing with a title, a new position; they were being coaxed into it with a plot of land. The blood of the myth was washed away by the seemingly banal. It is plain to see that the decision to acquit Orestes is a completely random one. Why was Clytemnestra not the one being exonerated? The simple truth is that the violence has to stop somewhere, and that ‘somewhere’ is always incidental. In order to end the bloodshed, any means will do. Anything goes. While we were watching Aeschylus’ words being performed in Russian, Popper, advocate of a simple democracy, had just died, and the timing seemed absolutely perfect.

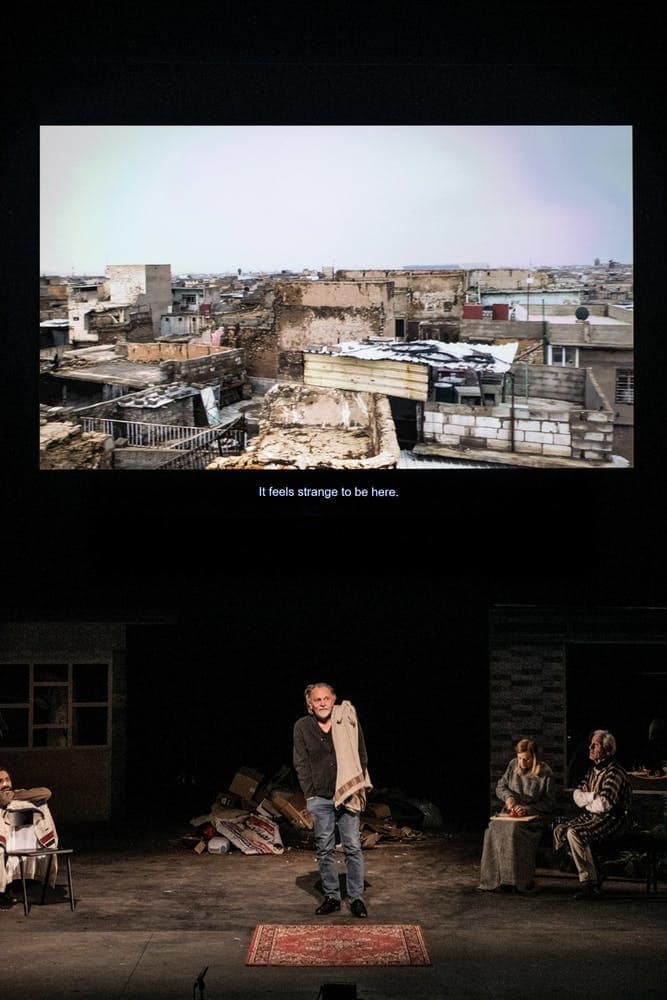

The year is 2019. Milo Rau is responsible for another revival of The Oresteia in Ghent. And what a revival it is. Rau really went to town with the play. He even went so far as Mosul, the rocky wasteland blown apart by ISIS, where up until 9 July 2017 the Caliphate’s flag flew high and proud.

For the adaptation of “The Oresteia” set in Mosul, student and professional actors staged the death of Agamemnon outside a bombed-out arts building.

For the adaptation of “The Oresteia” set in Mosul, student and professional actors staged the death of Agamemnon outside a bombed-out arts building.© Sergey Ponomarev

Critics have referred to the Swiss director (b. 1977) as one of the ‘most influential’ (Die Zeit), ‘most celebrated’ (Le Soir), ‘most interesting’ (De Standaard) and ‘most ambitious’ (The Guardian) artists today. Rau firmly believes in making theatre relevant to society at large (once again). In his 2018 Ghent Manifesto, he promised that it is not just about portraying the world anymore (after Marx), it is about changing it. Furthermore, he stated that the literal adaptation of classics on stage is forbidden, and added, “if a source text – whether book, film or play –is used at the outset of the project, it may only represent up to 20 percent of the final performance time.” He also added, “At least one production per season must be rehearsed or performed in a conflict or war zone, without any cultural infrastructure.”

Duly cautioned, my wife and I – both classicists, no less – headed to the theatre. To Rau, The Oresteia is just raw material he can work with. Is that a bad thing? No. Nevertheless, we must end up with a coherent and consistent story. What we are now presented with are several different stories.

© Fred Debrock

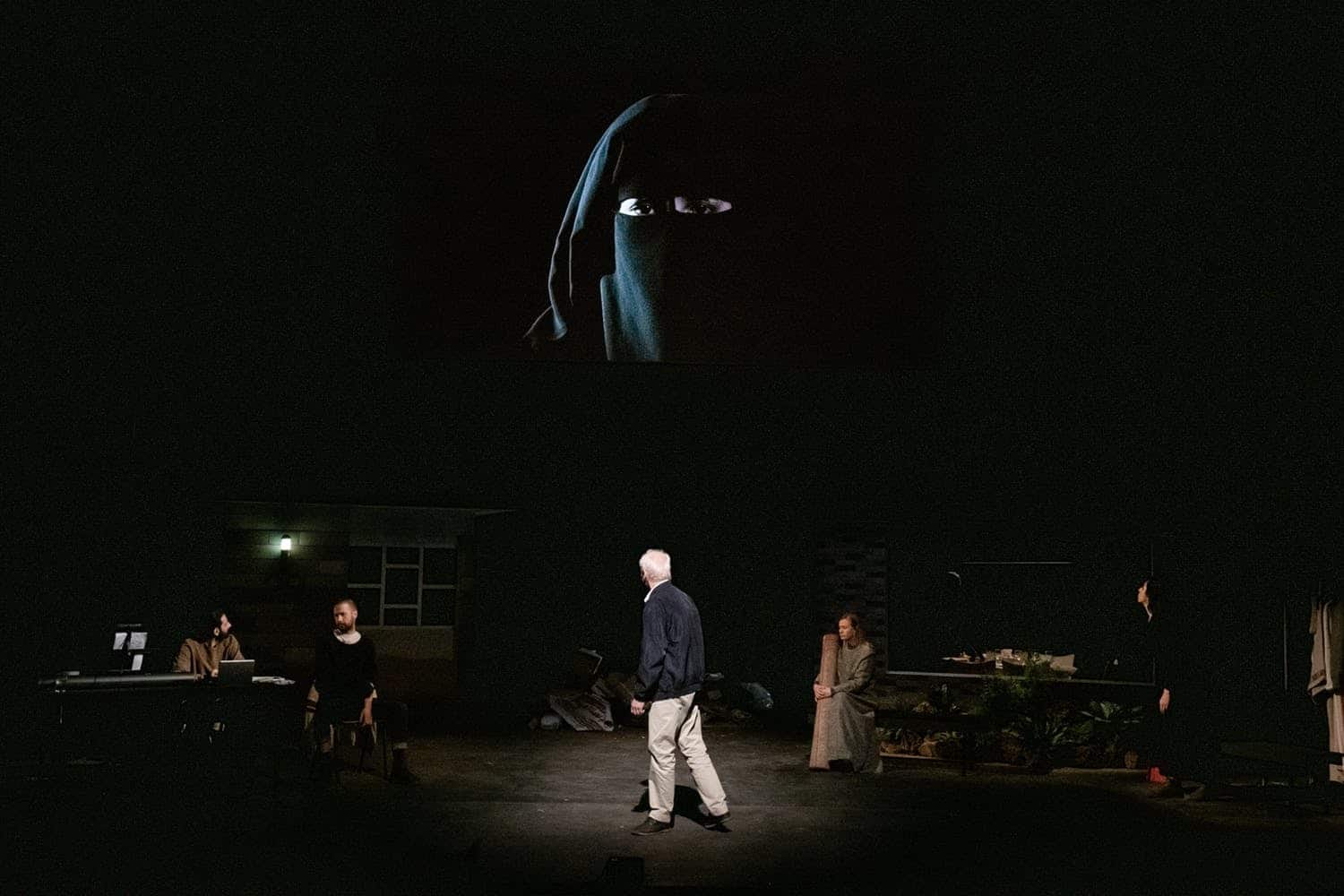

Together with the actors on stage we watch a video screen, which depicts how rehearsals of this classical piece unfold in the middle of a war zone. We witness, for example, the opening scene, in which a guard on the palace roof awaits the signal fire announcing the Greeks’ victory in Troy, and hence Agamemnon’s return home. We see the court scene set in Athens, where Orestes is acquitted of his crime, performed at breakneck speed. That story also blends into a story about the conflict zone and the ruined city itself. Before you know it, you are watching news footage, a reportage, a documentary. The actors also pay a visit to the ruins of the ancient Assyrian capital of Nineveh, near the Tigris River, and the Great Mosque of al-Nuri, which is being restored. We are told the story of a ferry that had just capsized on the Tigris River. Disaster tourism?

© Fred Debrock

On the actual stage, the actors recount/act out a summary of The Oresteia, at an incredible pace. We are faced with a mere series of scenes. Rau adds a rather bourgeois scene: a divorced couple is sat at a table, accompanied by their respective new partners (Cassandra and Aegisthos), and discuss their current situation in a painfully civilised manner. It actually turns out to be one of the strongest scenes. But what does it all mean? Rau draws parallels: in the video footage, for example, he asks the members of the jury in Mosul whether they ought to execute ISIS fighters, or rather forgive them. The ‘judges’ do not have a say this time, and keep quiet. The director imagines dear friends Orestes and Pylades as lovers. We are confronted with images of the rooftop ISIS fighters used to push homosexuals down from. Their French kiss on the Ghent stage is intended to express their regained sexual freedom, but even a very chaste version of this intimate moment was met with a lack of understanding and disgust in Mosul

© Fred Debrock

So, what did we actually watch? ‘The making of’ The

Oresteia, but not the actual play, according to my wife. Rehearsals in the run-up to a performance, set in a city in ruins, with a chorus made up of local actors. With local musicians who were allowed to bring their instruments back up from their basements, where ISIS had previously banned them. With a goddess Athena, played by a woman who lives in Mosul, whose husband was shot by ISIS.

Clearly, Rau has the best of intentions: to bring back an art form to a city shot to shreds, where buildings and art both had just been destroyed. He offers local cultural creators, actors and musicians, who have literally crawled out of their basements, a shot in the arm. However, a one-time-only visit to an area facing reconstruction of all of its infrastructure, let alone its cultural infrastructure, with a crew from a subsidised Western European theatre group, remains somewhat problematic. It is undeniably a – cf. Rau’s Manifesto – “statement”, but more specifically one relating to the Westerners who were flown in and back out safely. NGO-tourism?

© Fred Debrock

Orestes in Mosul is spectacular at times, but never quite succeeds in moving the audience. The play shows a great variety of things, but lacks coherence, and never really knows what its message is. It probably tells us more about the crumbling reality we live in, which constantly sees stories being told simultaneously, images being shown without any context, and where a so-called catharsis or some kind of atonement seems impossible to obtain. And it does not change the world. But we all know that is an impossible ambition.