The Porous Paradises of Bram Demunter

‘Everything exists side by side and can be shown as such’, says encyclopaedic painter Bram Demunter of his first solo exhibition. Demunter’s work is simultaneously comical and analytical, it confuses and provides comfort. Ancient Alligator Swimming from the Sea to the River remains on show until the 9th of October at the Tim Van Laere Gallery in Antwerp.

‘There it is!’ We’re about to give up when, on the right side of the street, we see the corner facade of the Falafel King. Why we didn’t look up the address with Google Maps is, in hindsight, not entirely clear. This is how painter Bram Demunter (Kortrijk, b. 1993) and I find ourselves following the Turnhoutsebaan for quite some time, searching frantically for the mythical falafel king that, he ensures me, serves the best falafel of Antwerp, maybe even of the whole of Belgium, Europe and the world.

Bram Demunter

Bram Demunter© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

As I take a seat at a wobbly table on the terrace, I feel like I am taking place in one of Demunter’s paintings: a skinny man pushes a pram filled with canned goods, a rustling elephant tree in a huge pot can be seen beyond. Couriers are driving back and forth carrying mysterious packets in all kinds of shapes and sizes, and a line of striking-looking individuals order kofta at the counter after being guided through the menu by the affably smiling king himself. And the falafel? It is delicious.

Demunter and I agreed to meet in Antwerp to visit his first solo exhibition. Ancient Alligator Swimming from the Sea to the River

is on show at Tim van Laere Gallery, which also represents other masters of figurative painting like Rinus Van de Velde, Ben Sledsens and Kati Heck.

After participating in group exhibitions nationally and internationally – most recently in the remarkable Regenerate at WIELS – Demunter, who specialized in the graphic and painterly arts at the LUCA School of the Arts and HISK (Higher Institute for Fine Arts), is showing alone for the first time this autumn.

The exhibition presents his most recent work, produced between 2019 and 2021. It includes paintings that, in their thematic multitude and painterly detail, resembling mash-ups of The Ghent Altarpiece, The Baths of Ensor and the Mughal miniatures of Abu’l-Hasan. The result is equally confusing and comforting, comical and contemplative.

Passion for collecting

Central to the exhibition is the titular work: a monumental painting depicting an archipelago. It is inhabited by an amalgamation of people and animals: dozing cows and giraffes, a colourful group of people taking an embalmed body to sea on a red boat, dogs that stare out over the waves from the central island, fenced in by chipboard, bearded heads that roll around a palm tree, ducks standing in a pond with burning sides, and hands in all kinds of positions and pigments that, from atop a floating island, signal to the sea.

Ancient Alligator Swimming From The Sea To The River, 2019 - 2021

Ancient Alligator Swimming From The Sea To The River, 2019 - 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Similarly, nature thrives in Demunter’s work. From ferns to rosebushes, from pines to Japanese cherry blossoms: it all covers the canvas abundantly, competing in visual crispness with the white-brushed waves around them.

‘Everything exists side by side and can be shown as such’, it escapes Demunter, as he thoughtfully chews on a falafel sandwich. He mentions it again later, as he guides me carefully past the recently installed paintings in the gallery. As a child, he was fascinated by collections. He could spend hours browsing encyclopaedias in the back of the car, searching for images of ‘all the fruit trees, Christ sculptures, and Russian politicians’.

Similarly, his paintings are preceded by a period of intense research, during which he combs his way through references, scientific studies, and Wikipedia entries omnivorously. Even his studio (a former tax office in Temse) gives evidence of this diverse interest: recently Demunter felt compelled to store his wide collection of found rocks, keys, and fossils collected on walks in labelled boxes.

Demunter’s works are the artistic result of this drive to gather

Demunter’s works are the artistic result of this drive to gather. He likes to see them as painted museums: they frame stories, histories and natural historic phenomena while inviting viewers to – often feeling as confused as the artist and the almost archetypical characters in his paintings – lose themselves in the multiplicity of the world.

Returning characters in his work are mermaids and men with baseball hats, elderly gentlemen, and dogs with human heads. You won’t find any individuals with a fixed identity (even though singer Cher and gallery director Tim van Laere show up from time to time). They act like stock characters

that originate somewhere in a corner of Demunter’s mind and filing cabinets, from where they are released now and again to expose something about our human condition.

Form, colour, and rhythm

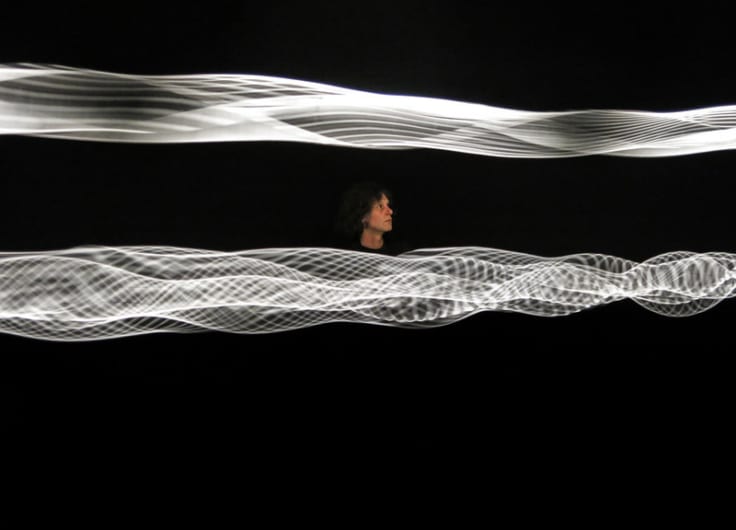

Although they are alienating, Demunter’s characters have something in common with the visitors of the exhibition. In his work Enclosed Garden Theatre, some figures are leaning over the hedges of an almost abstractly painted hortus conclusus, regarding the scene wide-eyed. Like the spectral beings that encircle them in the black emptiness around the garden, the visitors are positioned as looking over the shoulders of the characters, amazed by the paradise behind the bushes. The wide variety of social interactions that take place there are both recognisable, deeply human, and alien because, as Demunter remarks in a meandering text sent to me in preparation of our conversation (which forms the core of his research): ‘any real paradise can only exist in painting.’

Enclosed Garden Theatre, 2021

Enclosed Garden Theatre, 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

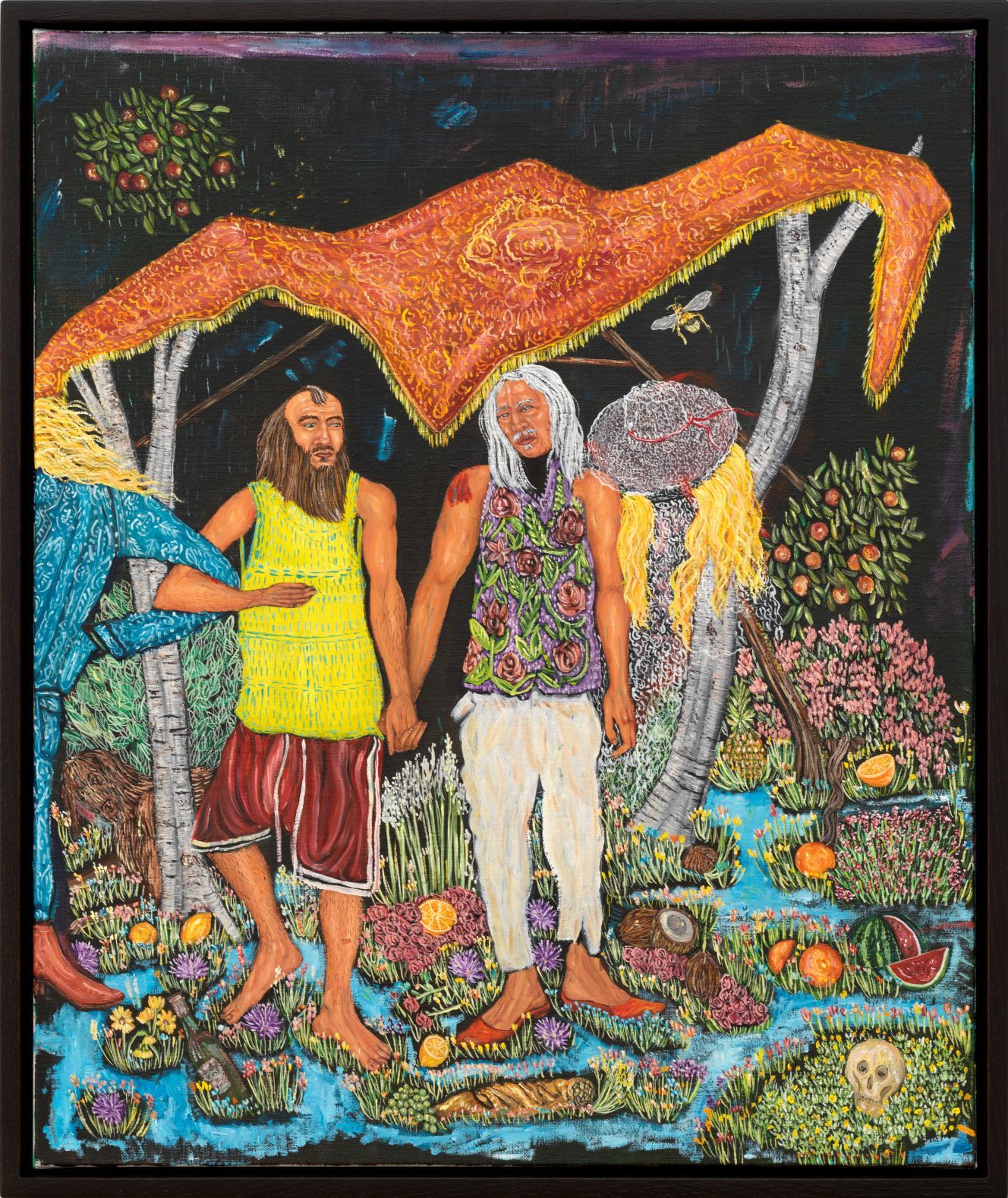

Demunter’s paradise doesn’t depict a higher reality. Instead, it shows the world as it could have been, in all its conflicting beauty and confusion. While a cheerful threesome dances the samba in Walk in the Flood Plain, a skull peeks at them from the grass.

Walk In The Floodplain, 2019 - 2021

Walk In The Floodplain, 2019 - 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

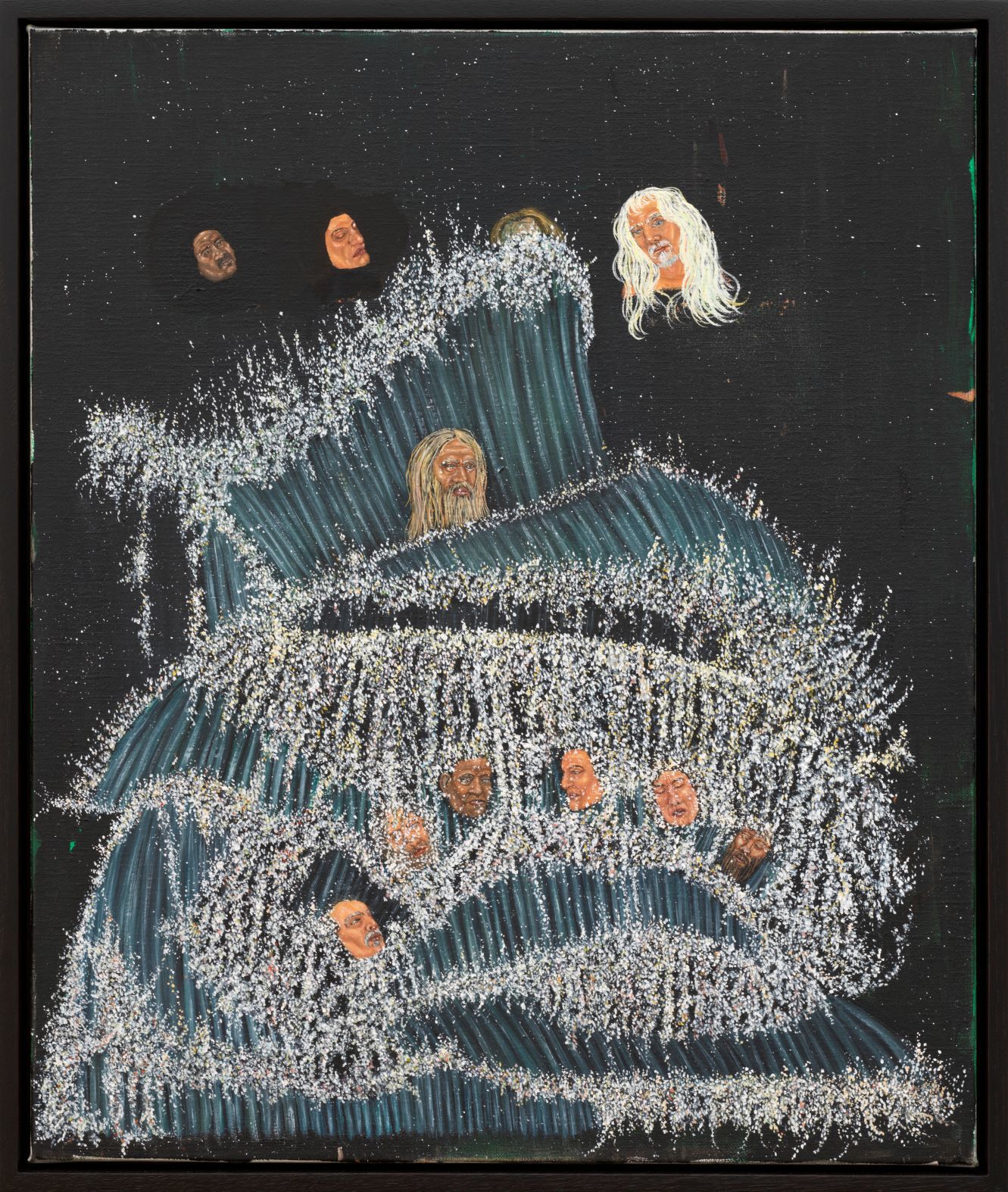

In Rogue Wave, the heads of marooned sailors dance in the surf of a beautifully stylized sea. In Demunter’s art, epic stories about love and death, beauty and violence, loss and seduction are told in unison. He guides my attention to a group of epic writers who, in the aforementioned red boat, float out to sea: ‘That is the writer of the Gilgamesh, and him, he wrote the Mahabharta, and there you see the author of the Ramayana. A bust of Homer floats in the water. And here flies – this is a personal joke – a Homerus swallowtail butterfly. But at the end of the day, none of this is of consequence. What carries weight for me is form, colour, and rhythm.’

Rogue Wave, 2019 - 2021

Rogue Wave, 2019 - 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Totality

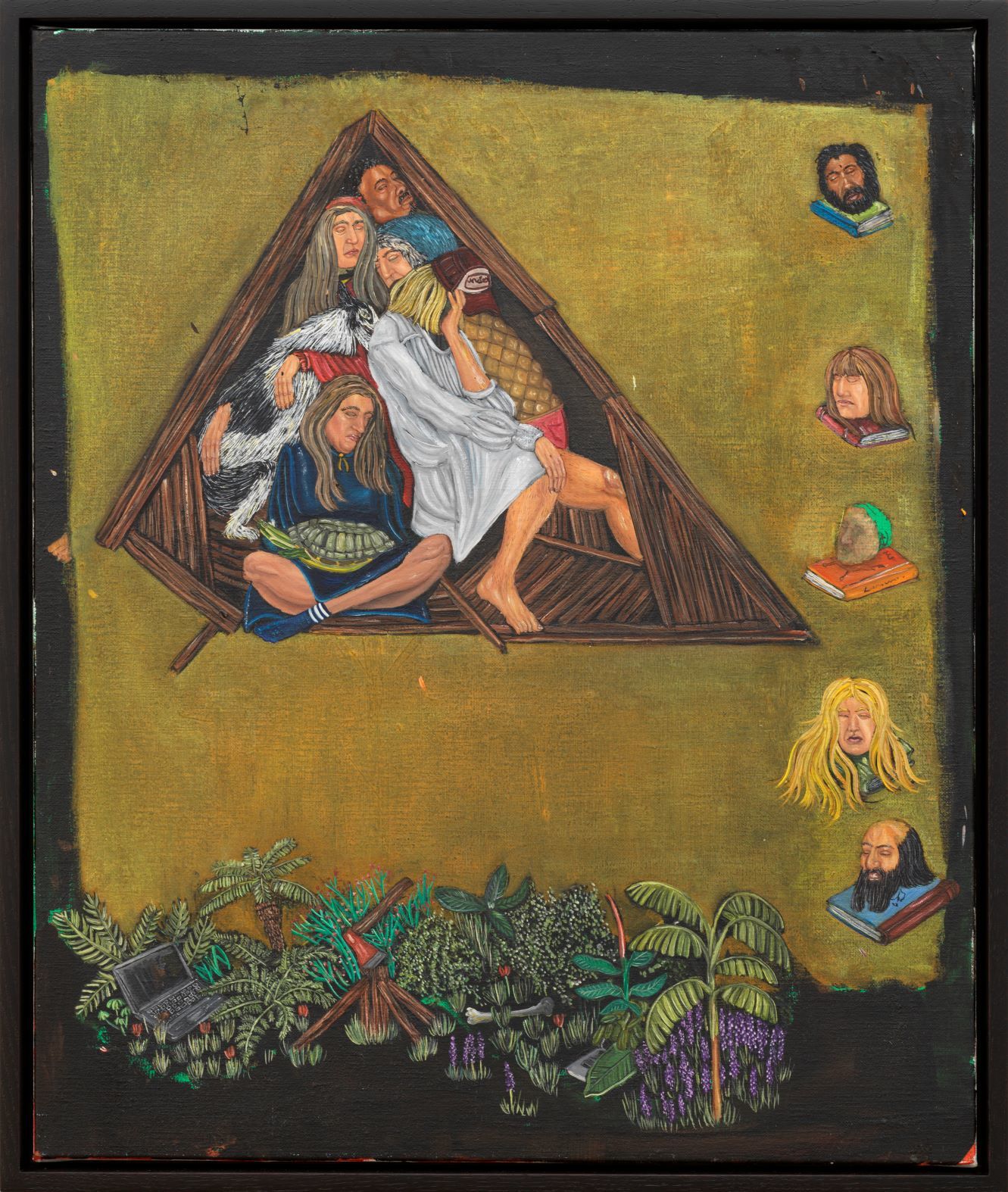

What matters isn’t that we recognise the turtle sitting in the lap of a lady, as depicted in Our Short Lives, but that we enjoy the totality that is brought about by the many natural phenomena and references to ancient stories. The painting is primary: Demunter is not interested in writing a new epic or twenty-first-century iconography. The many details in his works are not premodern analogies that (like the mediaeval ambience in some of his paintings may give cause to suspect) like symbols, refer to a kind of transcending deity, overarching idea, or generalizing statement.

Our Short Lives, 2019 - 2021

Our Short Lives, 2019 - 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

In his work, a wide variety of deities and elements of religious and ethnic traditions simply exist together, like mounted Homerus swallowtails in a crowded vitrine. Each is as valuable as the next in terms of exhibiting. Demunter refers to the famous ‘Aleph’ by the Argentinian author Jorge Louis Borges: the vantage point that is discovered in his short stories, from which the protagonist can oversee everything: all the crayfish and mountain crystals, all the stories of origin and outboard engines. This all-encompassing view is what Demunter wants to offer in his paintings.

Understory, 2021

Understory, 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

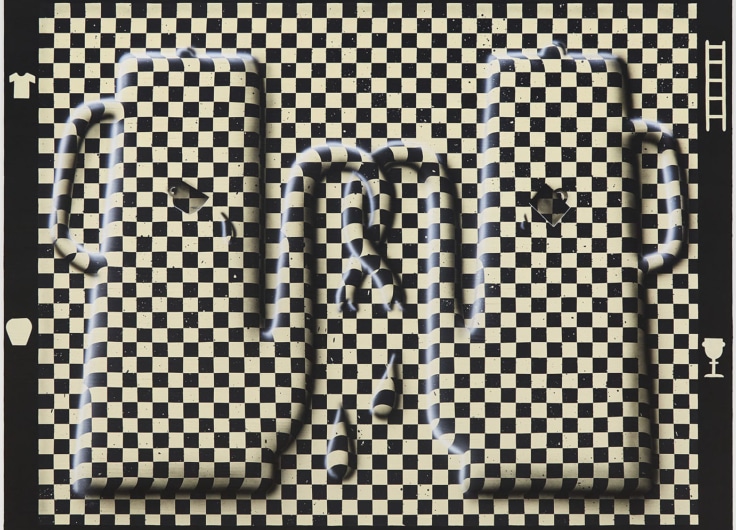

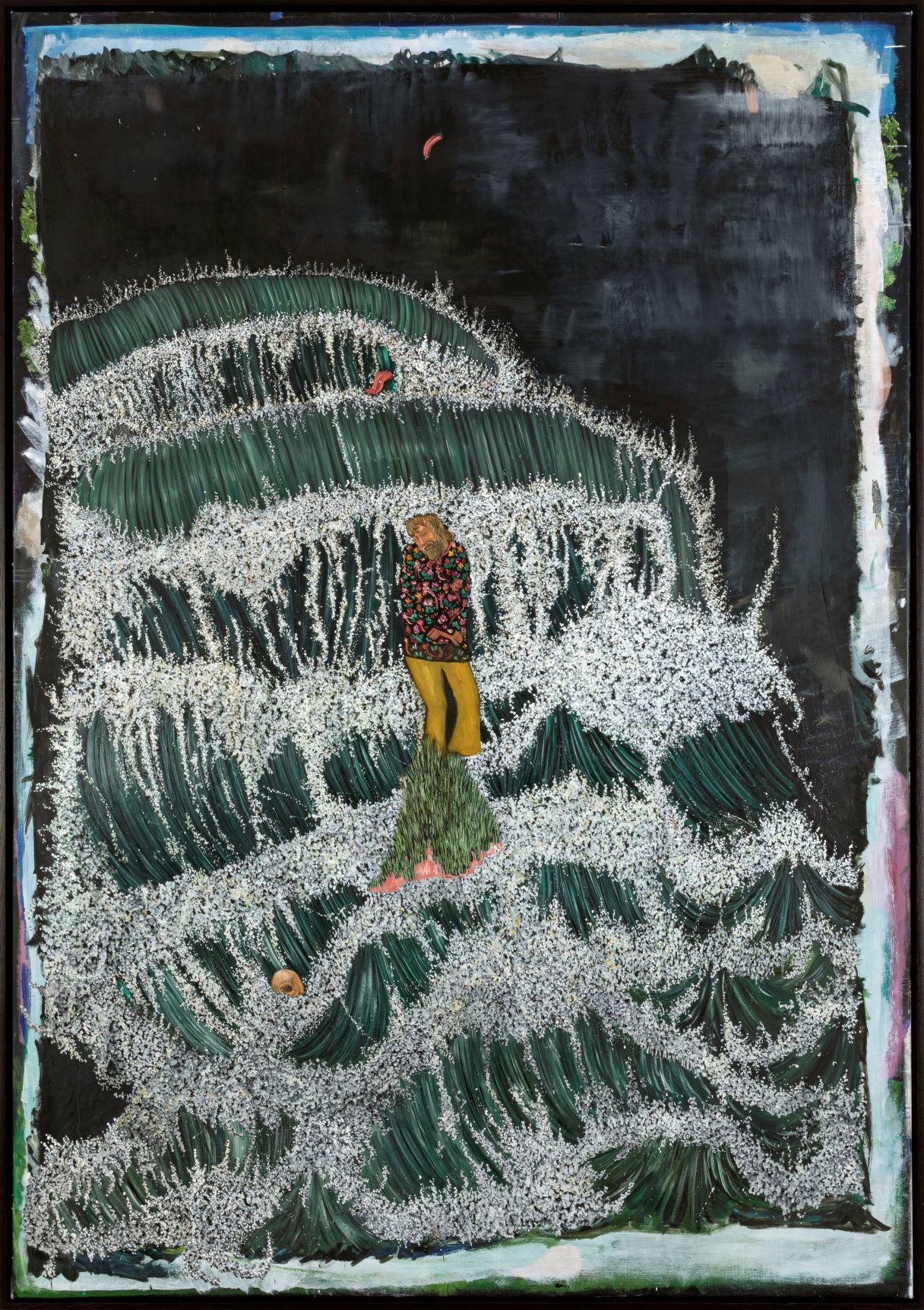

It translates into a very heterogenetic painterly technique that, like the thematic multiplicity of the works, browses through the history of art and combines many styles. In this way, the sea in Understory

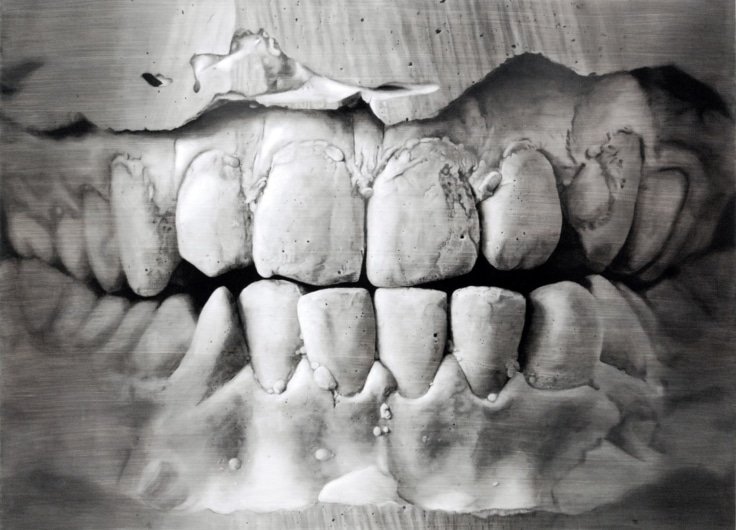

undulates in wild, abstract brushstrokes around a rock to which meticulous, almost photo-realistic pebbles and shells are painted (which I, as though with a trompe-l’œil, confused for real, superglued pebbles and shells). Impressionistically dotted treetops contrast with the chiselled, foamy heads of The Wild Onrush of the Waves, offering an almost sculptural view. Characters that could have come from the medieval Brothers of Lymborch or Matthew Paris are depicted next to the chocolate-brown walking-shoes and round knapsacks borrowed from our own Belgian comic tradition.

The Wild Onrush of the Waves, 2019 - 2021

The Wild Onrush of the Waves, 2019 - 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

Border between frame and world

Because of this open and indiscriminate perspective, Demunter’s works can be seen as porous paradises. The fence around the private gardens is open: the border between frame and world is not fixed. Like the real tree, displayed amidst the works on the gallery’s parquet floor, the frames that hold Demunter’s works function as an “etcetera”.

The scenes on the canvasses could extend endlessly beyond their structure (suggested, amongst other things, by the frayed edges of the paintings, often exposing earlier versions of the work). In this way, the works seem interconnected. The small boat that is floating around in one painting could just as well keep going until it moors up in different work. There are visual echoes that resound from one into another piece. Sometimes, smaller paintings like Hotspot Island are in fact intimate snapshots of more monumental creations.

Hotspot Island, 2021

Hotspot Island, 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

With Ancient Alligator Swimming from the Sea to the River, Demunter invites the viewer to travel from one island to another, much like the characters in sailor-tales about Sint-Brandaan and Jason and the Argonauts. From the pond holding fish with human heads in My Time in the Wetlands

to the stories saved in books and wooden chests in Our Short Lives; from the ark laden with fruit and Ensorian masks in Understory to the lost cartographers in The Wet Meadows.

The Wet Meadows, 2020 - 2021

The Wet Meadows, 2020 - 2021© Tim Van Laere Gallery, Antwerp

By following this trajectory, the visitor is encouraged to make connections between different works, stepping through their porous frames and wading from one canvas to the next. A quest, in effect, for the falafel kings of our world.

Bram Demunter, Ancient Alligator Swimming from the Sea to the River, until 9 oktober 2021, Tim Van Laere Gallery in Antwerpen.