The Rebellious Lives of Poet-Painter-Activist Breyten Breytenbach

Breyten Breytenbach has eighty candles to blow out. The flamboyant South African writer is known primarily for his poetry and his struggle against apartheid that led to his imprisonment. But Breytenbach is so much more. Portrait of a complex artist by his French translator Georges Lory.

Breytenbach is world-famous, especially as a poet. He has already published sixteen hundred poems. Words that recur most often are moon, angel, wind, darkness, murmur, seam, crown, death. At least, that is my impression as a translator of his work for the last forty-four years: now for a real statistical study. Huge flocks of birds flit through his verses, too. With his blessing, I gladly interpret these flying creatures and according to a landscape a bird might become a blue tit, a shearwater or a kite.

It has become a ritual: each year on his birthday, the 16th of September, Breytenbach writes a text in which he observes himself getting older. What will 16 September 2019 yield?

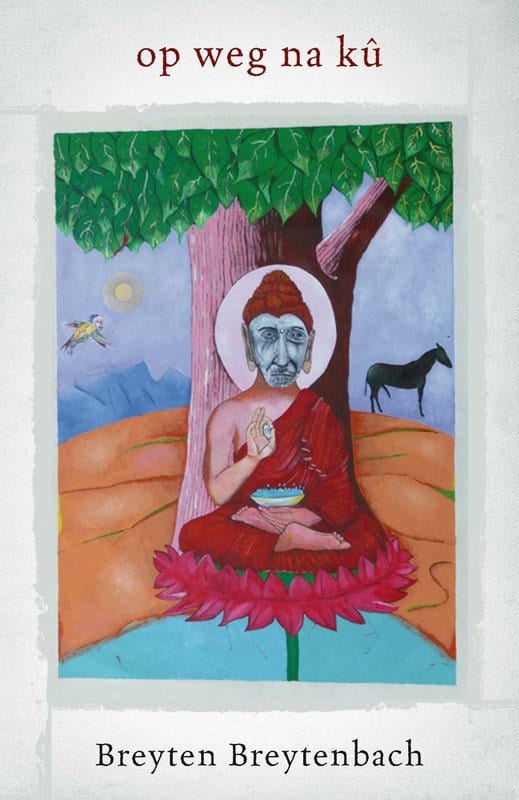

His latest poetry bundle, Op weg na kû (On the road to kû, Cape Town: Human & Rousseau), appeared in February 2019. The collection is composed of zen poems, interspersed with drawings and photographs. Breytenbach the poet goes out walking every morning, armed with a camera to capture unusual, everyday scenes. In this bundle, these are often small, dead birds.

On the way to kû, that condition or state where there is nothing, the poet professes his constant worry for what lies ahead, after life. The titles of his poems are eloquent: fluittaal as ars moriendi (whistle language as dying art), Mehr Licht! Mehr Licht (More light! More light), die woord word dood (the word is deadened), van die lewe na die dood (from life to death), die dood is ’n oordrywing (death is an exaggeration), bring doodgaan ooit verlossing? (does dying ever bring salvation?)

Sage – guerrilla – prisoner

In these contemplative poems we rediscover Breytenbach the sage. In Paris, he had formerly been a pupil of the famous guru Deshimaru (1914–1982); his first bundle in 1964 already featured poems about ‘in-spiration’ and ‘ex-piration’. The website Zen Deshimaru teaches that in kû there is neither matter, experience, action, consciousness, colour, sound, thought, knowledge, illusion, birth, death, suffering nor benefit. This ability to empty the mind later helped Breytenbach endure two years of solitary in Pretoria prison.

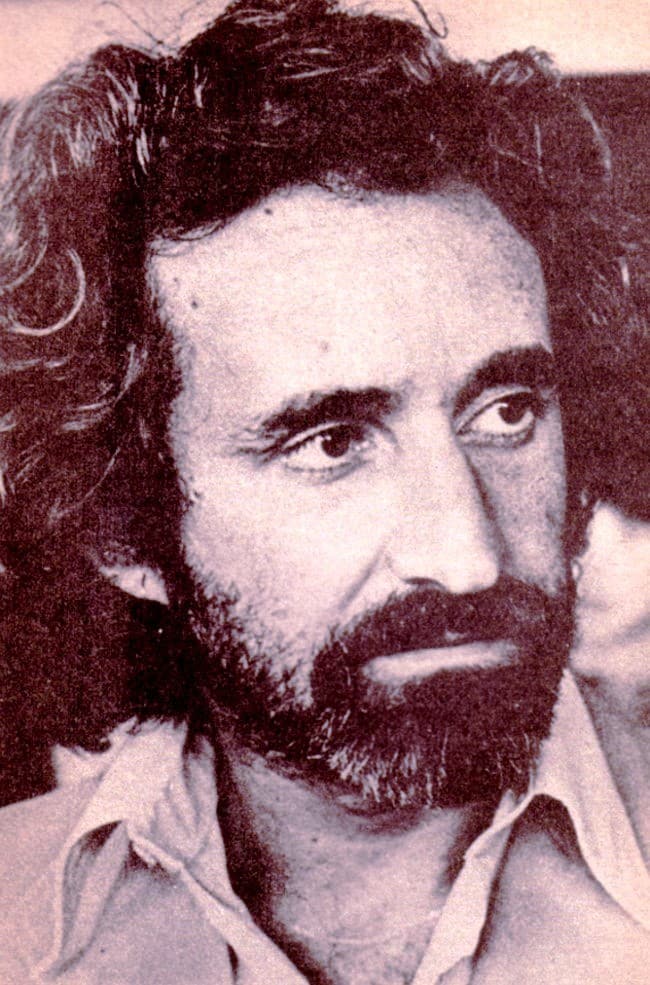

A young Breytenbach

A young BreytenbachMany Afrikaners cherish the image of Breytenbach the guerrilla, ‘as photogenic as Che Guevara and Leila Khaled’. During enforced exile in Paris, he encountered Solidarité, a network founded by the political activist Henri Curiel (1914–1978) to help clandestine militants across the world, which once counted the Indonesian-born Dutch writer Adriaan van Dis (b. 1946) among its members. Gilles Perrault’s book, Un homme à part (1984, Barrault) devotes beautiful passages to the friendship between the old resistant from Egypt and the young South African. Breytenbach founded a small association, Okhela, mounting strong evidence against the apartheid regime. In 1975, during a secret mission in South Africa, he was arrested and sentenced to nine years’ incarceration.

Breytenbach arrives at the High Court of Justice at his second trial, 1977

Breytenbach arrives at the High Court of Justice at his second trial, 1977Breytenbach the prisoner sketched an outline of himself in The True Confessions of an Albino Terrorist (1984, Taurus) and Mouroir: Mirror Notes of a Novel (2008, Archipelago Books).

White power so desired to break Breytenbach the rebellious son that he spent two years in solitary confinement. After a second trial, quietly and without forced confession, he was transferred to a regular prison where he was put to work in the warehouse. The warden there encouraged participation in sports and lent him a tracksuit, which is how he was able to meet Kobie Coetsee, then Minister of Justice, who was negotiating a prisoner exchange with several countries. Breytenbach would be released before the end of his sentence.

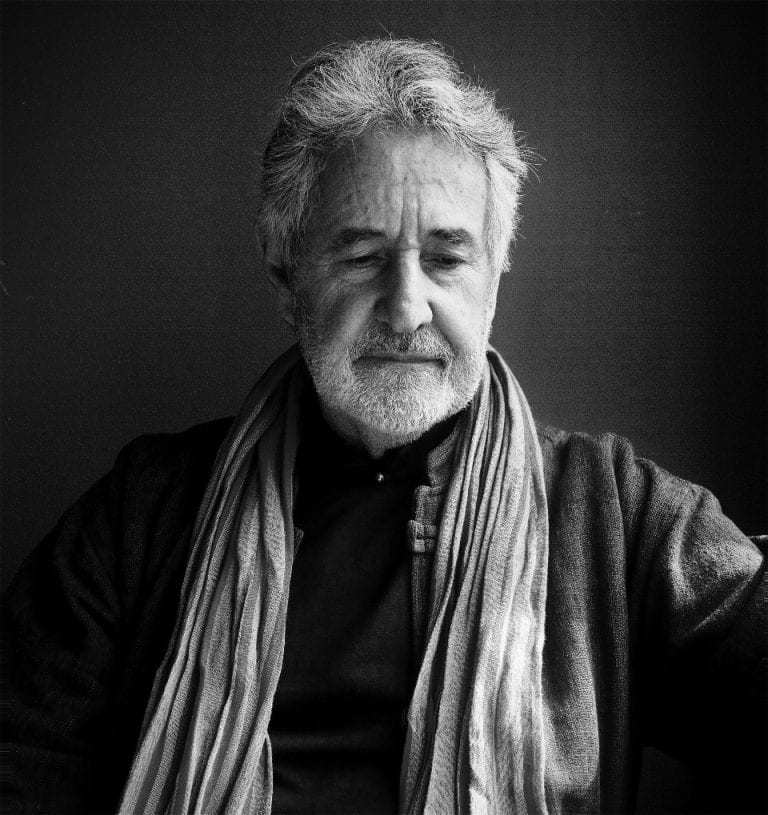

Painter - philosopher

As prolific as the poet, Breytenbach the painter paints incomplete characters. From a debut with drawings in black pen, he eventually moved on to portraits and self-portraits in colour. In a strange reversal of history, some of his works were removed when radical students denounced the colonial past at the University of Cape Town.

In his bundle Op weg na kû (On the road to kû) we see two angels mating on a mountaintop, Leonard Cohen with a falling bird of prey and a writer with a machine that rattles off words, above which hangs the mask of a snowy owl.

Breytenbach the philosopher

developed the concept of the ‘middle world’. Four books that mix essays, fiction and poetry express what he thinks. Dog Heart. A Travel Memoir

(1999, Harcourt Brace) is about reconciliation and identity, crucial issues in South Africa. This wording hits the spot: ‘Only Afrikaans makes the Afrikaner an Afrikaner’. The man continually on the move departs here from the principle that it is not possible to make progress if one forgets where one comes from. Intimate Stranger (2006, Archipelago Books) is about writing and the writers who form a diaspora. L’Empreinte des pas sur la terre (2008, Actes Sud) considers his love of movement. Notes from the Middle World: Essays (2009, Haymarket Books) brings into focus the space in which tolerant and intelligent minds can transcend all boundaries.

Public figure - political militant - orator

During apartheid, Breytenbach was a public figure. In Paris, he found himself constantly approached to explain the harsh reality in South Africa, since the media preferred the impertinent opponent over the more predictable ANC delegates who did not speak French. Breytenbach’s great contribution to resolving the conflict was bringing together for the first time South African intellectuals in Dakar in 1997. Thanks to the talent of the late lamented Frederick van Zyl Slabbert, the support of Abdou Diouf, then president of Senegal, and Danielle Mitterand’s France Libertés foundation, white South Africans were able to meet the intellectual leaders of the African National Congress (ANC) in exile. It was the first step in the dialogue that would lead to democratic elections in 1994.

The Dakar meeting was decisive for Breytenbach, who became a true pan-African militant, both co-founding and for a long time leading (2002–2010) the Gorée Institute/L’Institut Gorée to consolidate democracy and development in Africa. Encounters on this island off the coast of Dakar, a symbol of slavery, and elsewhere on the continent aiming to dismantle the barriers between Anglophone, Francophone and Lusophone countries prompted him to set up the Pirogue (canoe) collective, to publish a beautiful, multilingual yearbook, Imagine Africa.

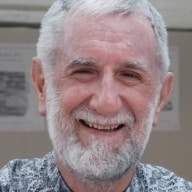

Breytenbach today

Breytenbach todayThe success of Breytenbach the writer goes together with an exceptional charisma: Breytenbach the orator can bring an audience into rapture. I have seen him at work in various places. In Paris at the Maison de la poésie, inclining attentively towards the asker of a question. And in Johannesburg on a winter’s evening at the house of writer Dominique Botha, in the select company of intellectuals including Achille Mbembe. It is often his diction that people notice, more than his ideas, because Breytenbach does not speak with a rolling /R/ like most Afrikaners. In Wellington, the village of his childhood, he can tell jokes all night.

Furious

Breyten Breytenbach has more strings to his bow: professor, polemicist, curious traveller. He has taught creative writing at New York University. He likes to pack his texts with quotes. Meanwhile, I’m no longer certain whether it was Wittgenstein who said that poetry, like mathematics, was for the youth. In South Africa he does not stop raging. Even before Mandela became president, he was already warning him about the corruption of some of his comrades; today he still regularly denounces the shortcomings of South African democracy. The politics that seek to curtail the use of Afrikaans at university infuriate him. Like a bird, he is always flying off his bough to scour the world for striking images.

The man who has been a role model for two generations of poets writing in Afrikaans is now being studied at university. He does not use heteronyms to lead his many lives. Yet he has invented several pseudonyms, variously signing texts as Jan Blom or Jan Afrika, and he has also had fun corrupting his name to Breyten Breytaintain, the galley crook B. Breytenmud, or even Breyten Barkoutside.

The poet wanders between four homes and gallops across our blue planet, a stream of poems issuing under his hooves. Returning to a phrase of Matisse, who urged his hands to paint until song bursts forth, in 2017 he published an anthology, Die singende hand (The Singing Hand, Collected Poems 1984–2014, Human & Rousseau), under the same title in different languages. Call it unity in diversity.