The Rediscovery of the Bicycle

It once symbolised individual freedom, but nowadays it’s a source of growing collective frustration: king car has been toppled from his throne. Mobility policy in France, Belgium and the Netherlands is making way for the bicycle, with Groningen as a founding example.

Every city is different, but in the latest municipal council elections in Belgium (October 2018) there seemed to be considerable cross-party consensus on mobility. A survey by the newspaper De Standaard showed that 90 percent of lead candidate politicians agreed on raising the number of speed checks, designing junctions to prevent conflicts between weaker road users and motorised vehicles, and introducing more electric car charging stations and more space for cyclists and pedestrians in the city centres.

Across municipal borders, sustainable mobility was one of the most important election issues, and one where parties from the left wing to the right were often surprisingly in agreement. Although not everyone has the same understanding of the term sustainable mobility, almost all parties advocated dividing up roads to avoid traffic build-up, and reducing the number of over-ground car parks, as they attract too much traffic.

Mobility stirs up citizens, both urban and rural, the latter because they increasingly end up in traffic jams on their way to the city, as shown by the years of discussion around the construction of Antwerp’s ring road. The debate preceding a new circulation plan for Ghent city centre also took place at a national level. Supporters and opponents of the new plan, which was intended to keep through traffic out of the centre of Ghent, held diametrically opposed views, despite the fact that the centre restricted access to cars long before the introduction of the circulation plan and was even car free in many places.

Cycling in Ghent

Cycling in Ghent© Fietsbult

Nonetheless what happened in Ghent is not particularly innovative or revolutionary. Groningen, a city in the north of the Netherlands with slightly fewer residents than Ghent and a similarly substantial student population, introduced a comparable plan as far back as 1977. The city centre was divided up, making it impossible for motorised traffic to travel from one part to the next. The district circulation plan gave cyclists priority, a policy which has since been consistently pursued. The compact city has a cycle path network of more than 200 kilometres and a large parking garage to accommodate 9,000 bikes at the Central Station. By the turn of the millennium half of journeys made in Groningen were made by bike, making the city one of the foremost cycling cities in Europe, behind a few Scandinavian pioneers such as Copenhagen. An extensive network of public transport was also designed in collaboration with the provincial governments of Groningen and Drenthe.

This made Groningen a forerunner in the Low Countries; only later did larger cities such as Utrecht and Amsterdam follow suit, prioritising bikes and public transport. In 2018 Utrecht opened the largest bike parking garage in the world, with space for 12,500 two-wheelers.

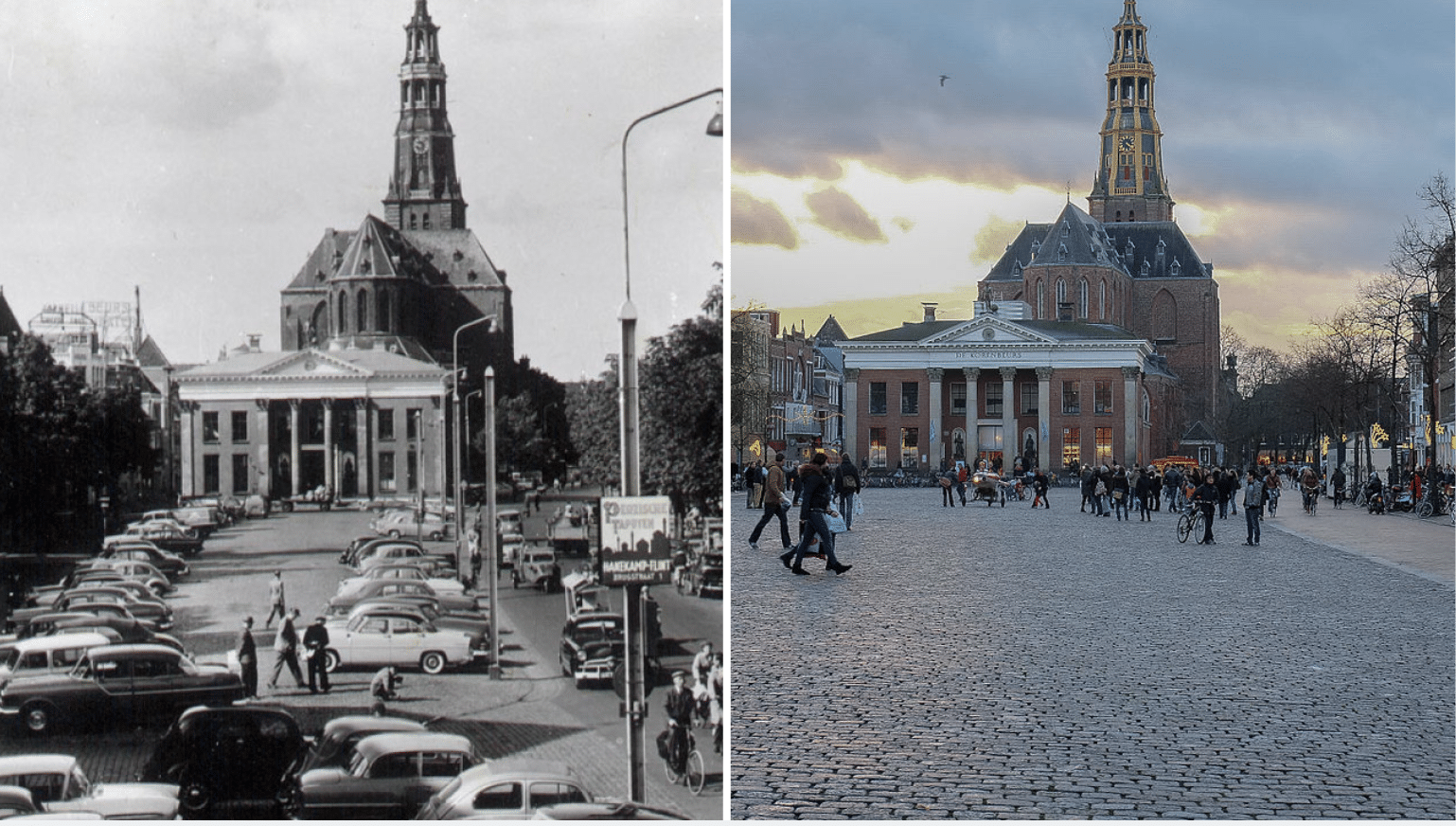

The Vismarkt (Fish Market) in Groningen at the end of the 1950s and today

The Vismarkt (Fish Market) in Groningen at the end of the 1950s and todayRacing cyclists and everyday cyclists

Foreign countries sometimes view these kinds of Dutch achievements with envy. ‘We’re a country of racing cyclists, but the Netherlands is a country of everyday cyclists,’ Christian Prudhomme, director of the Tour de France, concluded in 2012 during an interview with the newspaper NRC Handelsblad. In his office in Issy-les-Moulineaux, near Paris’s infamous Péripherique, Prudhomme was constantly irritated when he looked outside. The boulevard along the Seine had just been renovated, but there was not a cycle path in sight. ‘How can you get people out of their cars and onto their bikes if you do that?’ he sighed in resignation. ‘This is France, 2012.’

Starting in the 1950s and continuing for far longer than the Netherlands, France and to a slightly lesser extent Belgium pursued a mobility policy giving absolute priority to the car. The construction of the motorways, ring roads around the large cities and large car parks near the city centres determined the mobility choices of the population from 1950 until the beginning of this century. Trams disappeared from the smaller cities to make way for the car, the prime symbol of individual freedom. The increase in cars made cycling unsafe, which in turn led to an exodus from the cities, complemented, particularly in Belgium, by a policy of residential plots, industrial sites and offices outside the cities, accessible only by car.

That policy resulted in a vicious circle of car dependency, whereby policy makers saw the greatest possible facilitation of automobility growth as their main task. For a long time it was thought that car traffic behaved like a liquid, taking the path of least resistance, but later scientific research showed that cars behaved like gas, quickly taking up all available space. More or larger roads simply result in more traffic, not smoother flow.

From the 1980s the realisation slowly dawned that mobility policy needed to change, but only around the turn of the millennium did the tide slowly but surely begin to turn. In this process the cities, more than the rural governments, have been the great driver of a different mobility policy, with greater attention for pedestrians, cyclists and public transport, and much less for the car.

‘In the past decade consensus has certainly grown, and many cities are now promotors and executors of a strong cycling policy. This is no longer a left-wing or right-wing issue; every city administration wants efficient mobility, with the fewest possible adverse effects for the city space and the quality of life of residents and visitors,’ says Wout Baert, coordinator of Fietsberaad Vlaanderen, Flanders’ expertise centre for cycling policy.

The «Ghelamco Arena» in Ghent (soccer stadium)

The «Ghelamco Arena» in Ghent (soccer stadium)Baert notes that in recent years both policy makers and city residents have rediscovered the bike as a quick, efficient means of transport. It’s healthy and takes up much less space on the roads than the car. Eight to ten bikes can easily be parked in the space of one car, and cars are stationery 95 percent of the time.

The bicycle is also a very social means of transport. There are bikes in all price categories, and cyclists talk to one another while waiting at traffic lights. You increasingly see mayors and councillors travelling through their own city by bike, facilitating contact with the public. Cycling has also proven to be one of the most inclusive activities in cities. The cycling lessons organised by sports clubs and municipal services, appear to attract people of more diverse backgrounds than other activities.

Everywhere where even small measures are taken to curb car usage and promote the bicycle, bike usage increases faster than expected, as revealed in the cycling statistics in the Fietsberaad. ‘Some councils are surprised that things move so quickly,’ says Baert. But on closer examination it seems logical enough: the most important reason for parents taking their children to school by car, for example, turns out to be the safety aspect. Once measures have been taken to remove the danger, parents soon convert to using the bike along with their children. In a country in which we are told that 85 percent of children move too little, that’s an easy win. Since both cities and villages notice that investments in cycling policy pay off, cycling automatically receives more attention in local policy.

Baert points out that before WWII the bicycle held a prominent place. ‘Until the 1950s Antwerp was a more important cycling city than Copenhagen.’ At that point Belgium started to encourage car use, with the construction of infrastructure at the hearts of the cities, with features like a fly-over taking traffic close to the centre of Ghent, or the tunnels in the Brussels small ring. ‘In those days Denmark was a poorer country than Belgium, so it was decided that drivers would have to pay for the infrastructure themselves. The result was that cycling took root faster. In Amsterdam in the 1970s, too, the policy tipped in favour of the bicycle. In Flanders, bike awareness grew slowly from the 1980s, in part due to the establishment of the Flemish branch of the Fietsersbond (the cyclists’ union). But the real shift only took place at the end of the last century,’ says Baert. Belgium’s fiscally advantageous policy on company cars had also previously played a detrimental role. Employees were almost forced into the car, and often ended up living further from their places of work as a result.

Nevertheless, it’s certainly not all doom and gloom, and Flanders has not fallen behind in all respects. In recent years cycling policy has outstripped that of many other European countries. One in three people in Flanders cycles every day. When it comes to the percentage of journeys made by bike, Flanders comes second in Europe with 15 percent, after the Netherlands, racing ahead of the rest with 27 percent. Denmark comes in third with 14 percent. If we look at the whole of Belgium, instead of Flanders alone, however, the percentage of journeys by bike drops to 8 to 9 percent, a little higher than in France.

New policy in France too

Even France introduced a policy in recent years aimed at reducing cars in cities. But following the example of the Swiss city of Zurich, many French cities have opted for investments in joined-up public transport. The most famous examples are Bordeaux and Nantes, which set up fast, frequent tramlines with their own lanes. But certainly in Nantes there was also investment in reliable cycling infrastructure. According to the 2017 barometer of Villes Cyclabes, a French version of the Fietsberaad, in the category ‘cities with a population over 200,000’ Nantes took second place for bike-friendliness, after Strasbourg and before Bordeaux. Even Paris, once such a hostile environment for cyclists, where in 2008 a mere 2 percent of journeys were made by bike, scored points for the way in which cycling had progressed in recent years.

The French examples show that a cycling policy is best combined with investments in modern public transport

The French examples show that a cycling policy is best combined with investments in modern public transport, such as small electric buses or tramways. ‘The bike and public transport should be best friends,’ Baert argues, ‘and for that, frequency is more important than the size of the bus, tram or train. Unfortunately that realisation has not sunk in for everyone.’ In Flanders local councils often complain that they have too little control over public transport provision, which is determined by the company De Lijn. The examples of Groningen and Nantes show that public transport is best viewed at the level of city regions, something that Flanders is now trying to address through the implementation of transport regions.

The big turning point

With the rise of initiatives such as carpooling and the slow increase in the use of new, easily manoeuvrable cargo bikes, the general expectation is that car usage in the cities will drop further and cycling will enjoy an inexorable rise. The main challenge for the cities and surrounding regions is looking far enough ahead, because the infrastructure installed now must still be fit for purpose in twenty to thirty years’ time. That certainly applies to cycle parking, where the Fietsberaad advises allowing at least 5 percent of the space for bikes with unusual dimensions, such as cargo bikes or trailers.

But the most important turning point of recent years is the realisation among policy makers that a city is simply more attractive with fewer cars. You create more space for other activities, while also promoting air quality and quality of life for residents. This in turn gradually makes the city more attractive to young families, which currently all too often opt for residential areas on the periphery of the city.

‘Only by reducing cars can cities become attractive to everyone again. Slowly but surely a consensus is building for this. This is the big turning point of the past decade,’ Baert concludes.