The Resilience of a Bird: Two Poetry Collections by Mattijs Deraedt

In his debut collection De schaduw van wat zo graag in de zon had blijven staan (‘The Shadow of What Would Have Loved to Remain in the Sun’) Mattijs Deraedt closed his eyes to engage in introspection. It made it to the shortlist of De Grote Poëzieprijs. In Kleine wereld (‘Small world’), Deraedt keeps his eyes wide open and shows the reader a fragile but shining world, down to the smallest details.

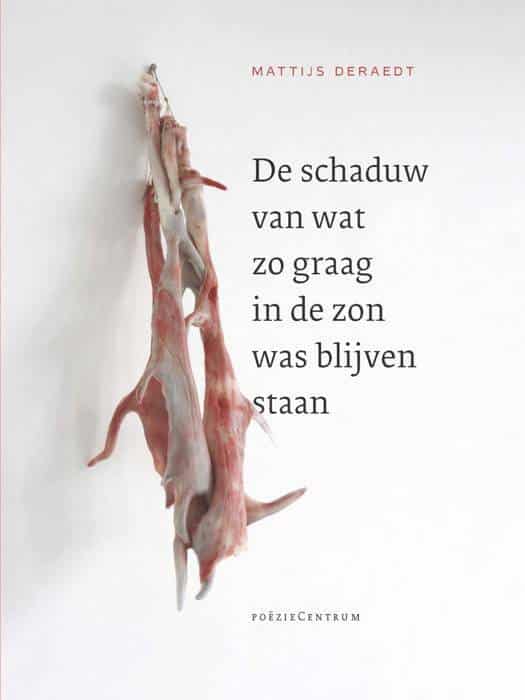

The cover of De schaduw van wat zo graag in de zon had blijven staan (2020), featuring a sculpture by Berlinde De Bruyckere, is both graceful and gruesome. Fragments of antlers hang against a white wall: soft, pink, stripped of grandeur and masculinity. According to S.M.A.K. (the Municipal Museum of Contemporary Art – Ghent), the remnants are from a dance performance about the metamorphosis of the mythical hunter Actaeon, transformed into a deer by the goddess Diana and devoured by his own dogs.

Unlike Actaeon, Mattijs Deraedt (b. 1993) is acutely aware of his gaze and the potential male gaze that objectifies women. He is so conscious that he closes his eyes and directs Diana’s bow at himself. He moves through the collection introspectively, dissecting and transforming his own masculinity.

The poet yearns for transformation, as in the poem ‘Water’. The poems are marked by dry self-mockery, are generally narrative, rarely have long stanzas, and contain clear punctuation. They often retain a mysterious character, with idiosyncratic metaphors and images that are sometimes difficult to grasp but usually successful.

De schaduw van wat zo graag in de zon had blijven staan (‘The Shadow of What Would Have Loved to Remain in the Sun’) is initially a paradoxical title: as soon as something is no longer in the sun, a shadow disappears. The shadows in this collection arise when people or things must give up their place in the sun and disappear. These shadows, cast on the living, are remnants we cherish, admire, or despise. They unconsciously influence, comfort, or hinder us. We encounter poignant examples: piles of children’s shoes in a concentration camp, ivory, a jar of pomade, a Jacques Brel song, and societal expectations of manhood.

Deraedt speaks of shadows, but similarly of “echoes” or “mist.” The image of the kingfisher is intriguing in this regard. The first stanza of ‘Your Last Bid’ – “The day you died / a blue mist hung in my chest.” – resonates in the first stanza of ‘Strange God’: “I am a kingfisher / with a mist in my chest.” This kingfisher is a counterpart to the deer. While Actaeon’s transformation is a punishment and death sentence, Ceyx, the king of Thessaly, is granted a second chance when he transforms into a kingfisher. According to Ovid, Ceyx drowns at sea, and when his wife Alcyone finds his washed-up body, she first transforms into the “grieving bird” that is the kingfisher, followed by Ceyx himself. In the poem ‘Chalamet,’ the kingfisher is the metamorphosis of a bird who loves and mourns, a bird who survives its own death. It finds new life in its drowning, like a phoenix from its ashes. In a similar vein, Deraedt dismantles a dated form of masculinity and simultaneously constructs the new man, or at least the new Mattijs Deraedt.

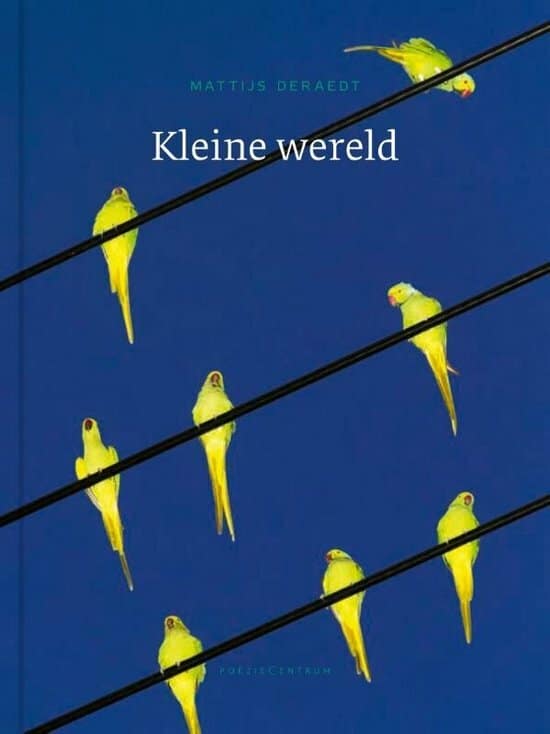

In his debut, Deraedt tightly closes his eyes, but in Kleine wereld (‘Small World’) (2023), he opens them wide. The smallest details of the poet’s environment come to life impressively. Sometimes the observer feels like an outsider, fearing to disturb the world around him with his presence. Sometimes there’s an overwhelming sense of unity, occasionally bordering on the ridiculous. More than in his previous collection, the poet employs humour and self-mockery, preventing the work from becoming too lyrical or preachy.

Deraedt’s intense gaze on the outside world stems from an uncomfortable feeling of instability and fragility. Humanity fills the earth without considering the consequences, or as we read in ‘The Body of the House’: “if you look away all your life from the things you make, / on what ground do you walk? Which cracks like capillaries / creak under your soles?” It feels like we must fully observe everything around us as a counter-reaction because it is still possible. Perhaps it is even a way to live in harmony with the earth, instead of dominating, molesting, or ignoring it.

Mattijs Deraedt

Mattijs Deraedt© Bert Potvliege

But is harmony even an option when the ground beneath our feet is collapsing? Deraedt gently urges caution at the end of ‘The Body of the House’: “let the dogs sleep / and stay lying on the ground.” Perhaps that’s why the observer often lies quietly somewhere: like a stone among deep-sea fish, an inconspicuous rock in a field with birds, on the bottom of a swimming pool: “Now don’t rise, now don’t intervene.”

Despite the confronting reality, the poems sometimes contain something unexpectedly hopeful: a fresh and fairly unique quality in the current poetry landscape. By closely observing nature, we see its perseverance and resilience: even broken trees continue to grow, and the two rose-ringed parakeets that Jimi Hendrix releases with peaceful intentions in ‘Dark Earth’ propagate vigorously throughout the country: “From the dark earth of his mouth they have ascended, / to the dark earth of the sky they will bear their fruits.” The parakeet, like Ovid’s kingfisher, finds life in the most unlikely environment.

Whether the hope in these poems is futile or not, Deraedt gives the reader unadulterated pleasure by opening up his environment, his small world, and revealing an infinite universe bursting with life. Everything we no longer pay attention to and assume is silently waiting for us is constantly moving. The ground beneath our feet can sink or crack open like a wound. But sometimes, like the field filled with green parakeets in ‘Field of Parakeets,’ it can just as well float: “Then the field begins to tremble and rises towards the sun.”

Mattijs Deraedt, Kleine wereld, Poëziecentrum, Ghent, 2023, 80 pp.; De schaduw van wat zo graag in de zon was blijven staan, 80 pp.

This text is a translation of the Dutch review originally published on de lage landen.