The Rise of the Citizen Historian

Universities are increasingly calling upon volunteer researchers for large-scale history projects. They collect and report information or enter data for further study. What motivates these ‘citizen historians’: the thrill of the puzzle, sensationalism, or a sense of historical injustice? And do they close the gap between academia and society?

For decades, droves of local experts, amateur historians and genealogists have been scouring the archives of Flanders and the Netherlands. They cobble together private collections and in the best cases produce publications. A newer phenomenon is that universities and other research institutions are recruiting citizen historians to staff teams of hundreds of volunteers. In stuffy archives from Groningen to Ypres to Paramaribo, they bring haunting stories to life about life, death, and everything in between. Historic and wartime traumas can last as long as three generations, so the motivations for many citizen historians are often strikingly personal. But how does that then align with objective historiographies?

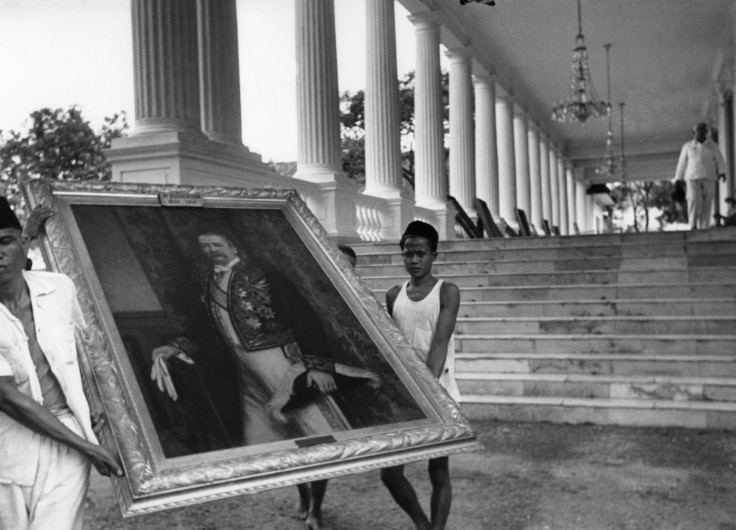

At the end of 2017, research into newly disclosed Surinamese Slave Registers was completed under the supervision of Coen van Galen, lecturer in ancient and social history at Radboud University Nijmegen. It was a large-scale academic project based on crowdfunding and crowdsourcing, relying on volunteers both for funding and data processing. “The actual investigation barely took four months, much shorter than expected,” says Van Galen. “We shared the results with our six hundred volunteers from Suriname, the Netherlands and Flanders.”

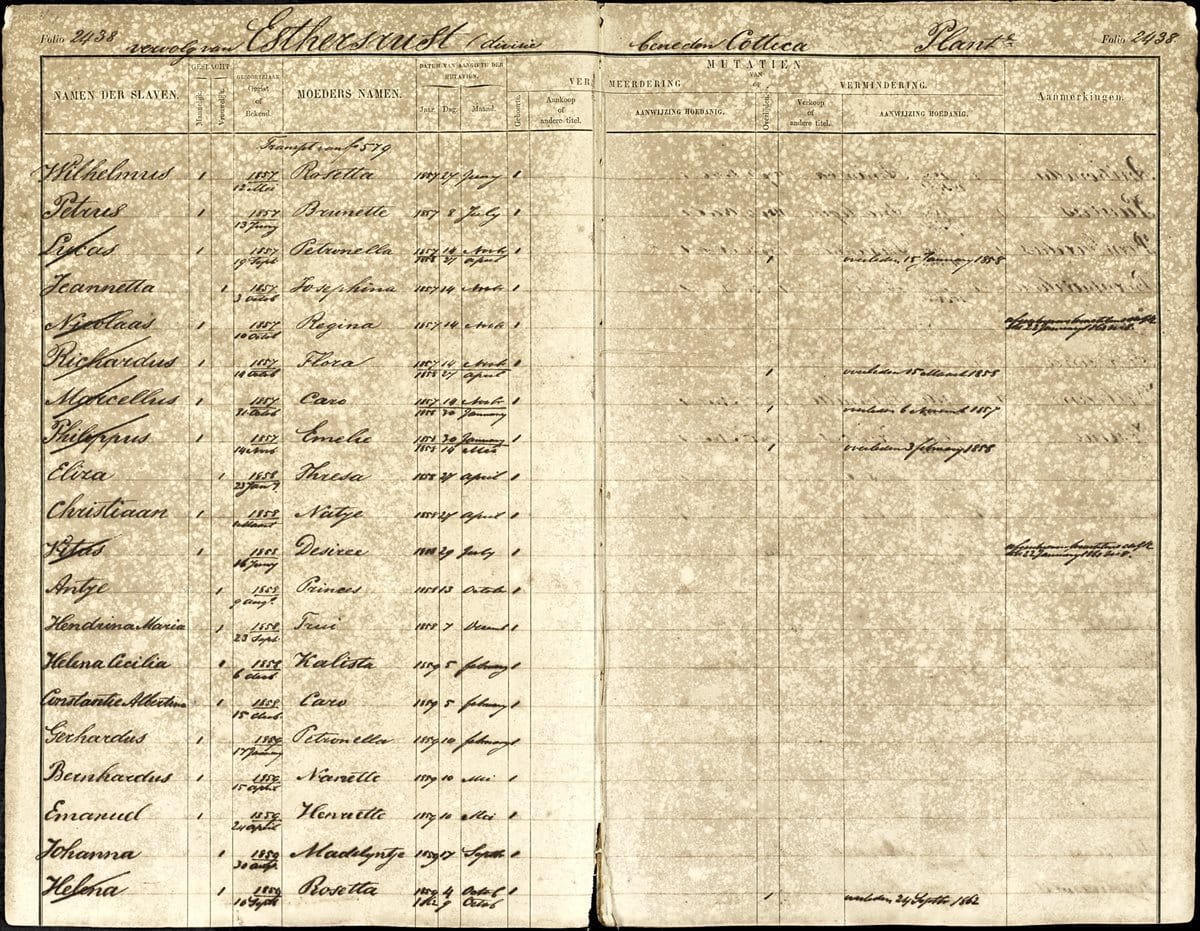

Pages from the Surinamese Slave Registers

Pages from the Surinamese Slave Registers© National Archives

These volunteers were set to work transcribing archival material to make it “readable”. By scanning archives, one amasses huge amounts of data. “But it takes transcription and annotation to make everything uniform and usable,” says Van Galen. “Meticulous and time-consuming work. But it is precisely the common goal that is very effective at keeping people on board. As a project manager, you must pay a lot of attention to interaction. Provide people with a well-run online forum where they can ask questions and post documentation. What are your team’s motives and background? Why is someone ‘less’ active online? Some give up after one attempt. So we organize training get-togethers from the very start of the project. Our volunteers are often archivists or other researchers, geologists, teachers, or experienced genealogists. People who already know the sources. You have to take that seriously as a research partner.”

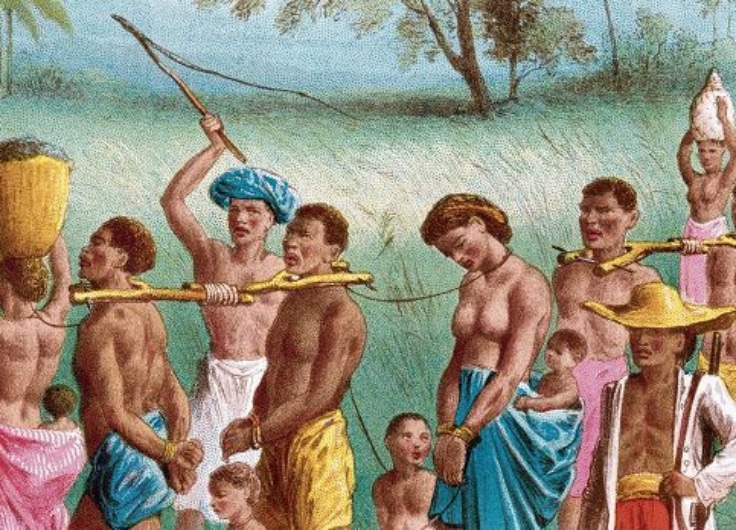

Slavery is shockingly normalized

Because slavery has become such a socially charged topic in the time of Black Lives Matter, the research received a lot of media attention. Those who took part often did so with the feeling that they were helping to rectify a social injustice. “That has brought great added value to the project. It has an ideological purpose without becoming an us-versus-them story. This history of slavery is not a pretty one, but it is our shared history and together we can give it the place in history that it deserves.”

According to Van Galen, the objectivity of the research does not suffer from a pinch of activism. “Even in the perverse context of slavery, it is all about people. There were ‘good’ slave owners, and someone who was enslaved was not automatically a hero. Shocking, for example, was the discovery of a former slave who became a slave owner himself, who bought children their freedom but kept their mothers in slavery. On birth lists, you see how one page further, those babies have died within the year. That is upsetting, it leads to interesting conversations, but it does not influence the research. All these stories are very enriching for the volunteers, especially when it comes to the Surinamese and distant Dutch descendants of those involved.

The social map of a century

Against all odds, there was still an intact death register to be found in Antwerp for the period 1820-1946. Historical demographer Isabelle Devos (University of Ghent) led the research: “The SOS Antwerp project (Sociale Ongelijkheid in Sterfte – Social Inequality in Mortality) arose from this discovery. We started this project at the request of my colleague Angelique Janssens from Radboud University, who had been conducting a similar study in Amsterdam. We are part of an international network in which we compare causes of death.”

Schoonselhof cemetery in Antwerp. Through the SOS Antwerp project (Social Inequality in Mortality), registers of causes of death of Antwerp residents are being researched

Schoonselhof cemetery in Antwerp. Through the SOS Antwerp project (Social Inequality in Mortality), registers of causes of death of Antwerp residents are being researched© City of Antwerp / Martien Willems

Angelique Janssens: “Thanks to the work of 800 collaborators, we completed data entry for the Vele Handen project (Many Hands Project) in April 2020, which mapped causes of death in the city of Amsterdam. Now a large number of the volunteers who helped on the Vele Handen project will move right on to the next project, which entails mapping patient registries in Amsterdam hospitals on another platform. We will soon know who was in hospital throughout the entire nineteenth century – how long after their visit they died, who they were, and what is on their birth and death certificates. Our volunteers also entered the entire 1907 land registry and based on this we also know the rental value of the home where the deceased lived. Taken together, this data reveals an entire picture of that person.”

“Many infants also died,” Janssens continues. “They have no profession or income, so the search for their background begins with the land registry. We want to be able to say something about the social status for each individual. Our volunteers are real citizen historians, because they also help us solve all kinds of issues if we can’t find something in the archive. Certainly when it comes to obscure information about, for example, drinking water supply or sewerage.

Community building is therefore extremely important, emphasizes Devos. “There is a monthly newsletter in which we interview a volunteer and explain a disease from the past… and also an active online forum where volunteers can ask questions, where we share tips and tricks for data entry, and so on. We organize webinars, lectures, and trips, like to the Antwerp Schoonselhof cemetery. You can collect points and get book tokens. Rewards are important as they are a form of recognition. But it is not the main reason why people participate.”

Power, politics and emotions

Can data entry really be called a science? What are the nuances and are there gradations of their work, like compiling narratives? Angelique Janssens: “Yes, they often start compiling narratives of their own volition. It’s what many of the volunteers enjoy about it: finding out interesting things for themselves. Sometimes very haunting stories arise from this research. For example the wave of suicides among the Jewish population in Amsterdam at the start of the German occupation. Or someone who discovered that a German bombing raid had taken place in Amsterdam in May 1940. This had flown completely under the radar, I had never heard of it myself. That volunteer identified the names of all the people who had died in that attack, and sought out their next of kin. This led to a publication and a memorial stone. One relative had lost his brother as a child during that bombing, it brought tears to his eyes. The kind of closure that such research can bring to people is underestimated.”

Historian Bruno de Wever, who specializes in Flemish nationalism before, during, and after the Second World War also agrees that some amateur historians get stuck into a subject for personal reasons. De Wever is a co-promoter of SOS Antwerp. “In Deurne we installed twenty new Stolpersteine, bronze memorial stones set into the pavement. That was the result of a lecture that I gave about the collaboration of the local police during the 1942 raids on Jewish communities in which 137 Jews were captured. The local community centre ’t Pleintje in South Deurne delved deeper into that story, parsed through the archives, and documented dozens of personal stories. Then they published a book about it.”

Bruno De Wever: 'Exposing history requires commitment. That is exactly what you will find in citizen scientists'

De Wever expressed emphatically that in doing so, the non-profit organization was undertaking “citizen science”. “Born from personal motivation, with heartbreaking conclusions. Because this is about the murder of fellow citizens and their relatives, who spoke during the commemoration. People from the community center wanted to participate because the story cut so deep – all based on a seed planted by an academic. The Deurne district openly struck a mea culpa because this story had been swept under the rug for so long and had only focused on the police officers who had rescued Jews. It is incredibly powerful that citizens were able to achieve that. History is power, and never without obligation. Exposing it requires commitment. That is exactly what you will find in citizen scientists.”

Chronicles: the sunny days and local politics

University lecturer in early modern Dutch history Erika Kuijpers (VU Amsterdam) and fellow historian Judith Pollmann are the driving forces behind the Chronicling Novelty project: how did people get their news and information between 1500 and 1850, and what new knowledge reached them in what way? And then: what did they do with it?

“Chronicles are a great genre for investigating news gathering by ordinary people,” says Kuijpers. “They are very localized. That’s why we tried to involve people from those places in the research. The genre originated in the Middle Ages and has existed for a long time. Topics are often the weather, local politics, disasters and wars, so the texts lend themselves to comparison. One gains insight into the author’s position vis-a-vis the information. With Chronicling Novelty we have collected an enormous corpus of scans from archives from Ypres to Groningen. We upload these to the Vele Handen platform, where the volunteers transcribe and annotate them.”

Erika Kuijpers: 'Crowdsourcing provides a lot of data, but it also takes a lot of work'

Erika Kuijpers does not think that projects like these significantly improve the relationships between academia and civic society. “Of the volunteers who help to transcribe, few are interested in the full research question. The turnout during a project day is usually minuscule. Far fewer people actively participate in the actual transcribing than the number that registers for it. Those who do pick up the project do so because it’s a kind of puzzle. They ignore complex methodological and analytical questions. On balance, crowdsourcing provides a lot of data, but it also takes a lot of work. You need to instruct people well and actually monitor them constantly. Communication on the forum does yield an immense amount of data as well and also nuances in other domains such as linguistics – there is, for example, an extensive thread about proverbs. Ultimately that will probably also lead to a publication.”

Coen Van Galen’s research on the Surinamese slave registers resulted in an investigation of the entire civil registry of Suriname. “Nowhere in European ex-colonies was such an extensive population register preserved,” says Van Galen. “With all the births, marriages and deaths recorded between 1928 and 1950, we will be busy for at least three years: 300,000 records, which each need to be entered twice. With 470 people on board, we see the same dynamics emerging as during our first study.”

Coen Van Galen: 'I see it as a kind of education. Everyone who contributes to this project will pass it forwards'

Unlike his colleagues, Van Galen does believe that crowdsourcing helps to close the gap between citizens and science. “I see it as a kind of education. Everyone who contributes to this project will pass it forwards. Key moments of an investigation are picked up by local media. That wider audience in turn opens up further discussion, especially on such sensitive topics as slavery. All research results are freely accessible online and you see that material cropping up in theater, books, and discussions. That social impact is really what it’s all about.”