‘The Safekeep’ by Yael van der Wouden: When the Outside World Comes In

Set against a backdrop of family tensions and unprocessed desires, Yael Van der Wouden’s debut novel invites us to explore the profound impact of our family and history on our sense of self. While her book, longlisted for the 2024 Booker Prize, should be praised for its emotional depth and rich character development, The Safekeep suffers from its relentless pursuit of a grand denouement.

It’s not every day we get to witness an international bidding war for a manuscript by a Dutch author. As expected, Das Mag Publishers seized on this to whet the literary world’s appetite for Yael van der Wouden’s first novel. The reviews that have made it onto the cover are promising too: “Thrilling, shocking and heart-rending”, “monumental” and “an ingenious debut”. However, while certainly arousing curiosity, the blurb raises such high expectations that you can’t help but fear disappointment.

Yael van der Wouden

Yael van der Wouden© Roosmarijn Broersen

The global offers aren’t the only remarkable thing about this book. The Safekeep was actually translated from English. Raised trilingually, Yael van der Wouden (b. 1987) was born in Israel, moved to the Netherlands at ten, and later studied in New York. Creative expression, it turns out, comes most naturally to her in English.

After Van der Wouden’s essay about her dual Dutch and Jewish identity received a notable mention in The Best American Essays 2018, the English manuscript of her debut novel landed on the desk of a big literary agency. From there, it took off, with the rights selling to thirteen countries. The Dutch edition is the first to be published, by Chaos, a small imprint of Das Mag and cofounded by Van der Wouden herself.

The Safekeep tells the story of twenty-seven-year-old Isabel, who seems to be a product of her environment: her cold and distant mother passed away after an illness. At the same time, her two brothers were absent during this difficult period. She grew up in a large house in the countryside, which was passed to her family via an uncle during the harsh war winter of 1945 when she was eleven. She continues to live there after her mother’s death, assisted by a maid, Neelke. Isabel is conservative, obstinate and direct to the point of insensitive. Her days are filled with odd jobs and ensuring that the house remains unchanged. Suspecting the maid of stealing or carelessness, she starts a painstaking inventory of everything inside the home.

The arrival of her eldest brother Louis (the property’s legal owner) with a new girlfriend in tow instantly triggers a hateful reaction from Isabel. She finds Eva downright silly and annoying and dismisses her as just another flame. When Louis has to go abroad for work for a few weeks, he installs Eva in the big house with his sister. A confrontation is inevitable. A dynamic of attraction and repulsion ensues, with Eva making Isabel’s blood boil, yet Isabel is totally fixated on Eva at the same time. She keeps a beady eye on the woman: something about Eva irritates and fascinates her. Meanwhile, things keep disappearing from the house (China, cutlery, a casserole dish), which heightens the charged atmosphere.

Although the book raises many interesting questions, it’s a shame that it is so emphatic in its pursuit of a denouement

The relationship between the two evokes the film Call Me by Your Name (2018), which also features an outsider who comes to stay for a few weeks and inspires a mix of resistance and curiosity. Its protagonists circle each other in a sultry cat-and-mouse game until the moment of surrender when they find each other as lovers. Likewise, in

The Safekeep it soon becomes clear that the initial irritation isn’t a sign of distance. Still, of a connection: Eva touches something fundamental in Isabel (affection, her sexuality), which is difficult for her to get her head around and admit to herself. The peach from the film, symbolising the gratification of a sweet longing, is a moist, ripe pear here.

Isabel is taken aback, not just by the immense lust (for life) that is sparked, but also by her apparent interest in women. Previously, she’d firmly rejected her brother Hendrik’s homosexuality. However, Isabel gradually comes to realise that as well as the house, she has kept her mind closed off; she barely knows herself and feels constantly overwhelmed by outside forces. Isabel and Eva enjoy some wonderfully intimate weeks, but time is at a premium: it will all have to end again when Louis returns.

The Safekeep is a novel about the impossibility of keeping something exactly as you like it

The narrative works towards a climax: who is Eva really, what is she doing in the house and why are all these things going missing? Without giving too much away, it becomes clear that Isabel and her family didn’t acquire their home (which came fully furnished, down to the dinner service and silver teaspoons) by honest means but had it for safekeeping and stubbornly clung to it when the rightful owners returned—a tragic course of events that was by no means exceptional during World War II.

UK Cover of The Safekeep

UK Cover of The SafekeepEarlier reviews of the novel have justly pointed out that this revelation doesn’t come at the right moment if, as a reader, you’re aware of this history. The fact that you’ve been anticipating it for some time undermines the narrative arc. Although the book reads well and raises many interesting questions – is Isabel’s closed character rooted in trauma? What exactly happened between her and her mother? – it’s a shame that the novel is so emphatic in its pursuit of a denouement: it robs the reading process of a degree of freedom and openness and leaves us with something that feels less than “monumental”.

The writing style is fairly sober, with language that feels a little prim at times due to the slightly dated diction (such as the exclamation “Oh, pooh!”, coming from a grown woman) and sentences ending in long dashes. However, arguably this makes sense as we’re dealing with a voice that harks back many decades.

Isabel’s relationship with her elder brother Hendrik may well be the most interesting aspect of this novel. She was a mother figure to him when they were young (we are repeatedly told that, “He was once a child and she had held him through his night terrors”), but their bond weakened when a defiant Hendrik left the house to explore his sexuality. One flew the nest, and the other stayed behind, stuck in her ways. The beautifully drawn dynamic between Hendrik and Isabel, subtly alternating between loving tenderness, solicitude and old hurt, could have done with more space.

US Cover of The Safekeep

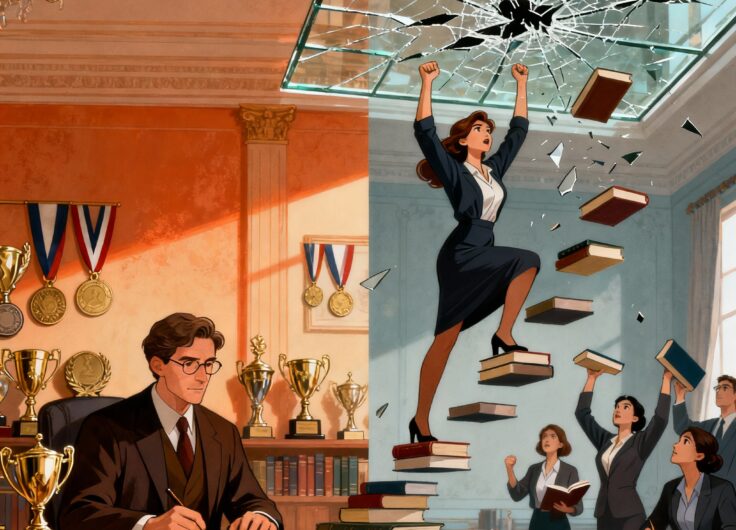

US Cover of The SafekeepUltimately, The Safekeep is a novel about preservation, about the objects and people around us making us who we are, about the impossibility of keeping something exactly as you like it when the outside world encroaches. Isabel thinks she has to fight tooth and nail for her own space, but eventually learns that what’s left when you do that is barely worth fighting for. Perhaps that’s why the story feels like a classic: its themes revolve around having a home, a family and a loved one, three fundamentals that ultimately force Isabel to delve deep inside herself to discover who she really is. It’s admirable that Van der Wouden has made this journey possible within the confines of a single house.

Yael van der Wouden, The Safekeep, Viking/Penguin (UK), Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster (US), 2024, 272 p.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.