The Shoah as the Essence of Marga Minco’s Writing Career

On 31 March 2020, we celebrated Marga Minco’s (pseudonym for Sara Menco) 100th birthday. Her oeuvre is an incessant attempt to come to terms with the war past by constantly creating new literary variants of it.

Marga Minco in 2018

Marga Minco in 2018© Thomas Doebele

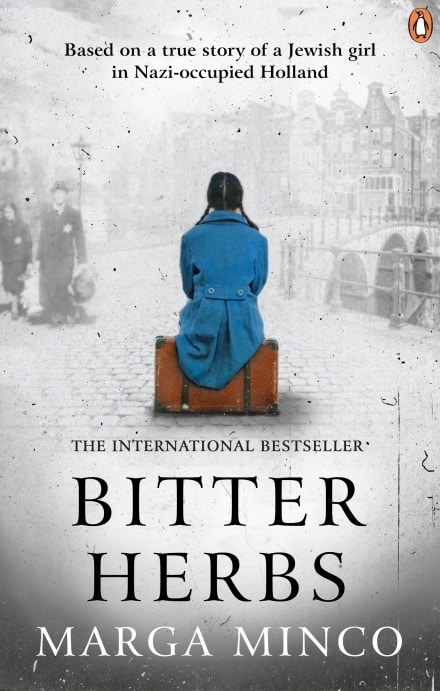

About a year ago, Marga Minco was presented with the P.C. Hooft Award for narrative prose, a well-deserved recognition although it came remarkably late. However, Minco’s modest oeuvre (five short novels, a sizeable volume entitled Collected Stories and a few children’s books) never completely dropped off the radar: her best-known novel, Bitter Herbs (1957), has thus far gone into its fifty-ninth edition.

Because of the success of Bitter Herbs, which would forever be associated with Minco by mainstream audiences, the author was frequently compared to some kind of Anne Frank, but one who did survive going into hiding. In 1960, renowned psychiatrist Bruno Bettelheim published his essay The Ignored Lesson of Anne Frank, in which he criticised Frank’s father Otto’s choice, who allegedly put his family in danger by hiding in the secret annex instead of offering his children the chance to take refuge at the right time, similar to what Bitter Herbs’ first-person narrator’s father does by leaving the door to the garden ajar for his daughter.

Bitter Herbs (1957)

Bitter Herbs (1957)Bettelheim also drew more attention to Minco’s testimony by stating that “the story of little Marga who survived remains totally neglected by comparison”. However, he did not pay attention to the literary dimension of Minco’s ‘little’ war chronicle. Even though Bitter Herbs is largely based on autobiographical experiences, the author was by no means similar to “little Marga” when the war broke out. In fact, she was a twenty-year-old journalist for the Bredasche Courant and her story of the persecution of the Jews in the Netherlands is not a first-person text in a narrow sense, but rather a subtle and complex literary work, permeated with allusions to Jewish culture.

The age difference with the heroine in Bitter Herbs underlines the child’s perspective, which sheds light on the innocence and the unpredictably of the Jews’ fate. This technique is typical of the literary approach characterizing the post-war reconstruction of Minco’s family history. She turned out to be the only Holocaust survivor, except for one of her uncles. Stylising memories and using imagination and symbolism as an important structural feature would later be considered some of the main characteristics of Minco’s oeuvre.

Survivor’s guilt

The Other Side (1959)

The Other Side (1959)Her prose also occupies a special position in Dutch and European Shoah literature, because Minco is one of the few Dutch Jews who were able to escape deportation. After returning to Amsterdam and various other locations after the liberation of the Netherlands, the experiences and emotions she evokes in her novels and stories, including The Address (1957) and An Empty House (1966), can be compared to those of concentration camp survivors: social isolation, self-alienation amid indifferent – even hostile – surroundings, and survivor’s guilt. And we must not forget about the fact that those who returned were shamefully robbed as it turned out they were not allowed to take back their possessions they had left in the care of acquaintances.

We are introduced to Minco’s completely unique voice by her ability to surpass this subject matter by repeatedly creating new literary variations of the theme in a continuous effort to process the war years. In Bitter Herbs, readers are struck by the austere style the author uses in order to tell us, as she herself used to put it, “as much as I can using as little words possible” about the unspeakable horror of the Holocaust, devoid of any sentimentality.

Alienation of man

In parallel with her sober-realistic account of extremely tragic facts, Minco changed her tack by writing rather fantastical stories that weren’t published until the seventies, entitled Mr Frits and Other Stories from the Fifties (1974). The theme here is the alienation of man. Owing to the absurd situations she describes in these stories, – which, at first glance, are not linked to the war – they fit in with a surrealist trend, which was rather typical for the existentialist era in Dutch literature.

The Fall (1983)

The Fall (1983)Another form of literary existentialism presents itself in Minco’s second novel, An Empty House, which deals with the adjustment difficulties victims of war are faced within the years immediately following the war. By adding more referrals to the first-person narration, the author suggests a stream of consciousness that aptly captures the main character’s – Minco’s alter ego – will to live, amidst an atmosphere of uncertainty, with dramatic consequences: a second protagonist takes her own life.

In Minco’s later novels, the understatement technique used from Bitter Herbs gradually makes room for the use of metaphors in order to better illustrate the key problem in her oeuvre. Her third novel, The Fall (1983), for instance, deals with an old woman who falls victim to a series of unfortunate events: she falls down a hole filled with boiling water – a thinly veiled allusion to the extermination camps’ crematoria – even though, during the war, she had been able to escape a raid by falling down the stairs at home.

Coincidence and predestination

The Glass Bridge (1986)

The Glass Bridge (1986)This brings us to the next few topics, i.e. coincidence and predestination of the survivors. Once again, metaphorical language reveals how survival in times of war has been touch and go for the author in The Glass Bridge, Minco’s 1986 Book Week Gift. The title is taken from the Dutch idiom “op het glazen bruggetje geweest zijn” (“having been on the little glass bridge”), meaning ‘having been in mortal danger’. That image simultaneously evokes the idea of a barrier and that of a crossover between the present and the past, between life and death, where crossing over to the other side can have fatal consequences but could also be a way to connect to the dearly departed, e.g. the father of the main character who she meets again in a dream, as well as her brother. Fantasy and reality are intertwined in this sophisticated tale, in which Minco thoroughly explores her subject matter on the road to her inner quest.

In her later works, Minco was continuously preoccupied with the memory of her deceased family members, as is evidenced by her final novel, Bequeathed days (1997). In that sense, her oeuvre reads like both a lasting testimony of and an ode to everyone who was allowed to live on in her stories: the ultimate message of her exceptional writing career.