The SieboldHuis Displays a Unique Japanese Collection of a Vain Doctor

Premodern Japan used to be just as closed as modern-day North Korea. The little information that emerged came from Dutch merchants. Philipp Franz von Siebold, a German physician and naturalist in the service of the Dutch East India Company, created a collection that to this day is unique in size and kind. The SieboldHuis in Leiden provides insight into the everyday life of nineteenth-century Japan, but its temporary exhibitions also tie in with current topical issues.

For more than two centuries, Japan was completely cut off from the outside world – no foreigners were allowed to enter and no Japanese to leave the islands. This total isolation was the result of the sakoku

policy formulated between 1633 and 1639 under the shogunate of Tokugawa Iemitsu, who had just recently forged Japan into a political entity and did not tolerate outside interference. It was only when the American commodore Matthew Perry threatened to destroy half the coast with seven gunboats in 1854 that the borders were reluctantly opened.

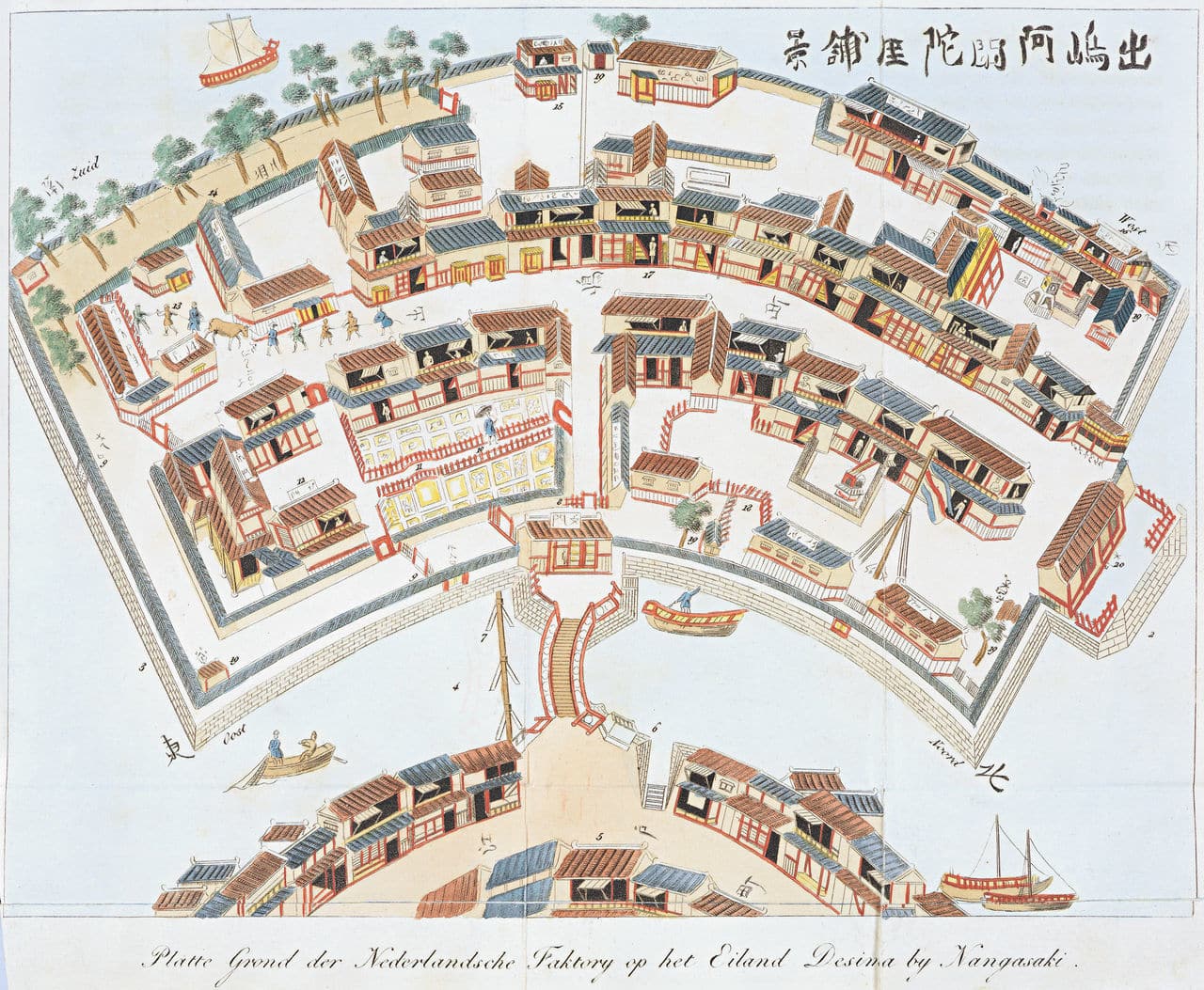

During that long period of international seclusion, there was one Western entity with which Japan did maintain contact: the Netherlands. To be precise: the Dutch East India Company (VOC), the trading company that went down in history as the world’s first multinational. It had fifteen representatives stationed on Deshima, a man-made island in the port of Nagasaki. The small community lived in an area no larger than Dam Square in Amsterdam and was only allowed to sporadically go out to trade with the locals. The most famous inhabitant of Deshima was Philipp Franz von Siebold, who was on the island between 1823 and 1829. On his return to Europe, he settled in Leiden, where he founded the museum in his home that we now know as Japan Museum SieboldHuis.

Ground-plan of the Dutch trade-post on the island Deshima at Nagasaki, between 1824 and 1825

Ground-plan of the Dutch trade-post on the island Deshima at Nagasaki, between 1824 and 1825© Wikipedia

Adventurous doctor

In the first room after leaving the entrance area, visitors can watch a film introducing them to the namesake and founder of the museum. A former employee of the nearby Museum of Ethnology has crawled inside Siebold’s skin and narrates his life in a voice-over. The old boss reveals himself to be a loud-mouthed, bragging chest beater. It might all sound a bit theatrical, but according to legend he is purported to have been quite full of himself, so it strikes the right tone.

Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866)

Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866)© Wikipedia

Accompanied by animations of maps and photos, the ersatz-Siebold sheds light on his biography. He was born in Würzburg, Germany, in 1796, the scion of a family of physicians. He himself also goes to study medicine, but out of a desire for adventure, enlists with the VOC, pretending to be a Dutchman. Via Batavia (present-day Jakarta) he ends up in Deshima, where his medical expertise is soon noticed by the local authorities. He receives indigenous objects as gifts from Japanese patients and collects plants. He even set up a medical training institute, which is now called Siebold Memorial Museum. When he is invited to the quadrennial court trip to the Japanese capital Edo, he has maps made along the way and exchanges medicine prescriptions with the shogun’s ophthalmologist in exchange for a valuable kimono. However, these types of transactions are strictly prohibited. When the vessel with which Siebold wants to export his treasures is shipwrecked and the cargo washes ashore, his crime is discovered, and he is exiled.

Painting showing Philipp Franz von Siebold with a telescope, Dutch personnel and Siebolds Japanese wife with their baby-daughter watching an incoming Dutch sailing ship at Deshima, 1811.

Painting showing Philipp Franz von Siebold with a telescope, Dutch personnel and Siebolds Japanese wife with their baby-daughter watching an incoming Dutch sailing ship at Deshima, 1811.© Wikipedia

The spirit of Siebold

After this dramatic tale, which also features a Japanese daughter who later becomes Japan’s first female doctor, the voice actor invites the visitor to enter the building haunted to this day by his spirit. That house is still – or rather: once again – in the same condition it was in in when Siebold moved into it in 1829. It consists of four older houses that were merged in the eighteenth century. In the basement, you can find the original Delft blue tiles and hooks where food used to be hung to keep it out of reach of rats and mice. The rear façade is seventeenth century and shows the coat of arms of its earlier residents, the Van Beveren and Paap families. The impressively curlicued façade is out of eighteenth-century Baroque. Fun fact: this façade was the model for the 97th addition in the series of miniature houses that airline KLM expands upon every year featuring an eye-catching building.

Japan Museum SieboldHuis

Japan Museum SieboldHuis© SieboldHuis

The visitor does not get an exact idea of how Siebold lived here. Nothing remains of the original interior. Siebold’s lifelong chronic lack of money compelled him to rent the ground floor to the student fraternity Minerva. He retired with his collection to the top floors and mostly stayed in his villa in Leiderdorp, where he cultivated plants brought from Japan.

Up until 1997, the stately canal house housed a district court, and insufficient maintenance caused the historic building’s interior to become horribly run down. Restoration began, after the lawyers had left the premises, and three years later it was already sufficiently advanced to receive the then emperor of Japan and Queen Beatrix. The intense blue vase with image of the imperial chrysanthemum at the front door of the Siebold House commemorates this state visit. It wasn’t until five years later that the museum officially opened to the public.

Impressive collection

The building’s interesting architecture alone is sufficient reason to pay a visit, but the real draw is the collection. Despite his shipwreck debacle, Siebold managed to take some twenty-five thousand objects with him. Only the masterpieces are exhibited in antique display cabinets. There are few works of art among them. Siebold was particularly interested in objects that said something about the culture and nature of the closed island kingdom.

Dried tea plant

Dried tea plant© SieboldHuis

The natural history artefacts are displayed in a room. From dried plants – Siebold single-handedly ensured that the tea culture found its way to Indonesia – to a stuffed Japanese raccoon dog and various animal skulls. These specimens served as the raw material for the two thick standard works that Siebold wrote about the flora and fauna of Japan.

The Panorama Room

The Panorama Room© SieboldHuis

The other room on the ground floor, the large Panorama Room, is dimly lit. After all, vulnerable prints are exhibited here as well as the maps that Siebold managed to obtain when his lifelong exile was lifted in 1854 and he returned to Japan. Musical instruments such as the twenty-five-string koto, swords and bows are laid out in large display cabinets. Nor is there a lack of perfectly made lacquerware and netsuke, the artfully crafted belt button fasteners that are now considered a sought-after collector’s item. But equally interesting are the everyday consumer items such as a pair of socks, flip flops and even a toothbrush.

© SieboldHuis

The permanent collection is rotated on average every three years, but prints have a higher turnover rate. Temporary presentations are assembled in the large display case on your immediate left when you enter the Panorama Room that combine pieces of the Siebold collection with the museum’s own collection. This was created in 2018 with the donation by a private individual, which has since been followed by donors from all over the world, as far afield as Australia.

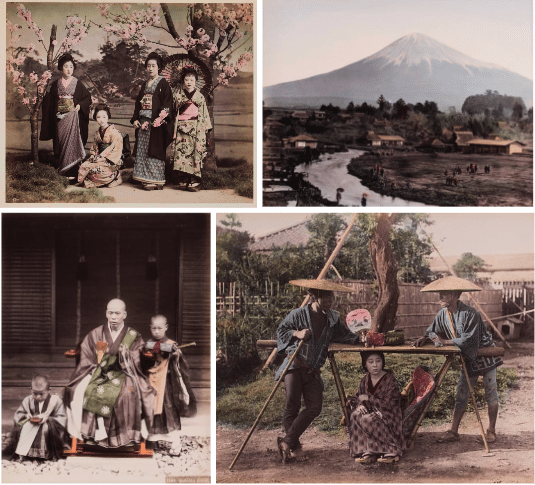

The permanent collection took up the ground and first floor until a decade ago and has currently been expanded to the second floor. This now affords more room for temporary exhibitions that respond to topical issues with remarkable frequency. When there was a debate in the Netherlands about showing nudity, the museum’s response was with Japanese nude photography. Likewise, the Fukushima nuclear disaster and commemoration of seventy-five years of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki were also included in the programming. Rarely seen nineteenth-century Japanese photographs from a private collection will soon be on display.

Pictures from the exhibition 'Japan on a Glass Plate. 19th Century Photographs from the Kurokawa Collection'

Pictures from the exhibition 'Japan on a Glass Plate. 19th Century Photographs from the Kurokawa Collection'© SieboldHuis

The SieboldHuis works closely with other cultural institutions in Leiden, from Naturalis to the Lakenhal. But the most direct connection is with the Hortus where there is a bust of the Japan explorer just like in the Siebold House back garden. Not as a grey-haired man with bushy eyebrows, a piercing gaze, and a chest full of ribbons, but as a young man with a slightly arrogant look in his eyes. In the Hortus he surveys the seven hundred plant species that he transplanted from Japan to Leiden. This includes the Japanese knotweed, perhaps the oldest specimen of this plant in Europe, which has become an outright pest and symbolizes the ecological disturbance caused by exotic species. This illustrates that the acquisition of knowledge in foreign countries is not always as innocent and harmless as the explorers themselves assume.