The ‘Silent Novels’ of Frans Masereel: Godfather of the American Graphic Novel

Up until twenty years ago, the Flemish woodcut artist Frans Masereel (1889-1972), most famous on the European continent for his “wordless novels”, remained virtually unknown in the US and the UK. However, over the past few decades, interest in his work has increased substantially in London as well as in New York. Masereel biographer Joris van Parys knows how that came about.

Frans Masereel, 1951

Frans Masereel, 1951© Louis Van Cauwenbergh / AMSAB

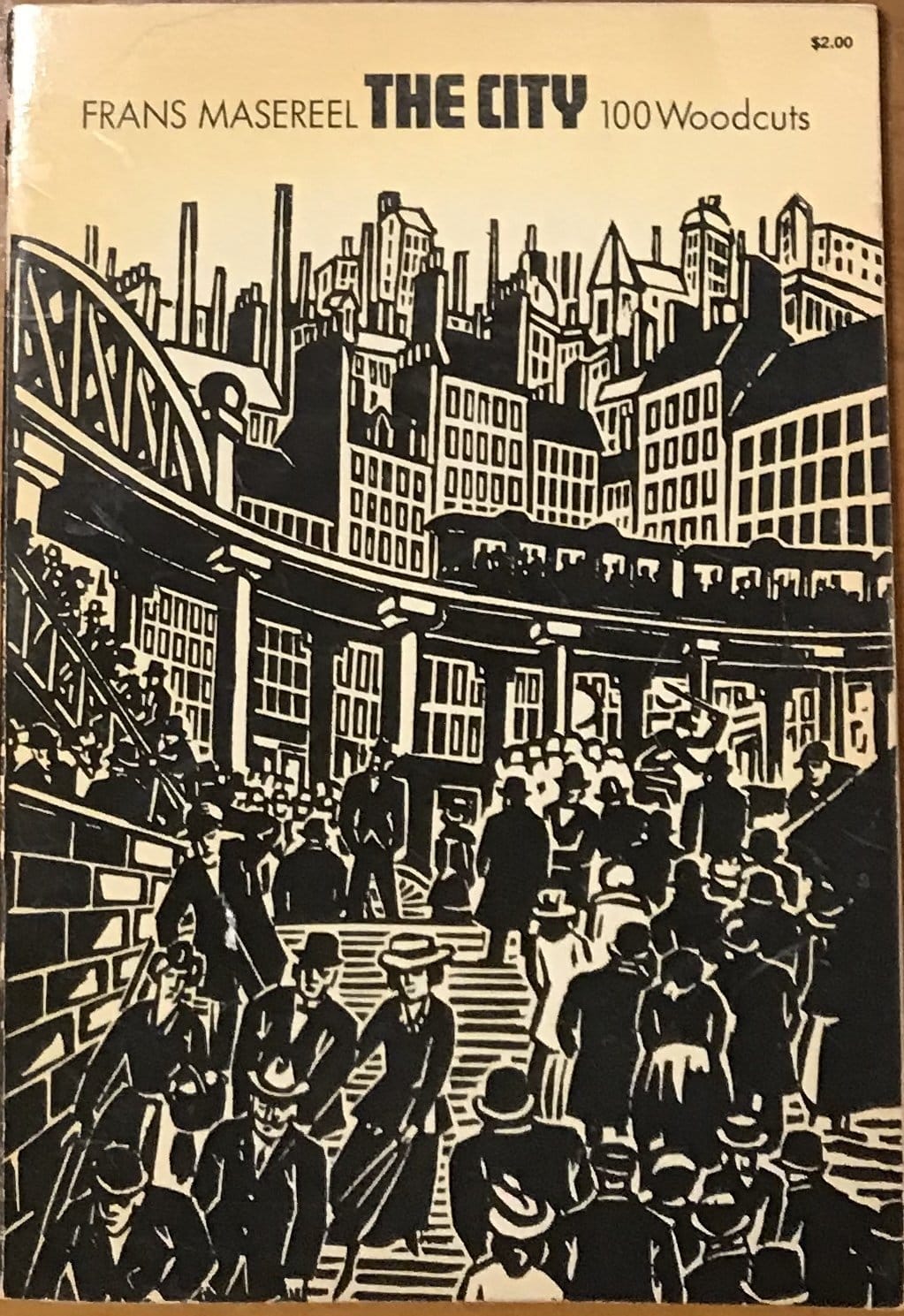

“Charging the static, blocky medium of the woodcut with the newly emergent force of cinema, Masereel created wildly kinetic visions…” This is how, back in 2015, Charles Siebert described in The New York Times Magazine the woodcuts of The City, Masereel’s impressive wordless book about life in a bustling 1920s metropolis. In 2017, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London displayed fifty of the one hundred woodcuts from the first limited editions published in 1925 in Munich (Die Stadt) and Paris (La ville). Curator Matt Williams acknowledged that London was quite late to realise the exceptional significance of The City – some thirty years after The Guardian’s laconic comment “only 65 years late” on the publication of the first British reprint (Redstone Press, London 1988).

Frans Masereel, American reprint of The City (paperback), Dover Books, New York, 1972

Frans Masereel, American reprint of The City (paperback), Dover Books, New York, 1972For decades the entire Anglo-Saxon art world ignored the timeless qualities of the woodcuts that earned Masereel’s graphic stories a place of honour in the European book art of the interwar period. Among the rare admirers in post-war New York was the Anglo-Irish critic James Stern of The New York Times who in 1948 reviewed Passionate Journey, the first post-war American edition of Masereel’s most acclaimed woodcut novel Mon livre d’heures (Geneva 1919). In the closing paragraph of his review Stern noted: “Unlike many other books, both of words and pictures, first published in the Twenties, Passionate Journey does not date. The problems it presents are more crucial, its philosophy more needed than ever.”

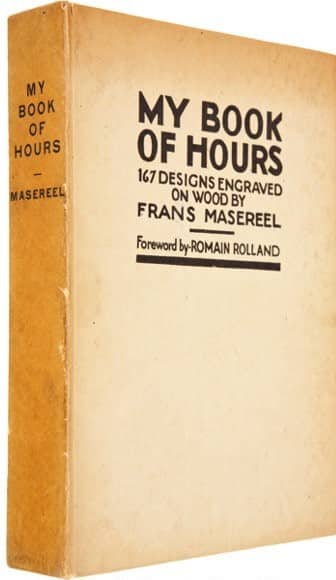

Frans Masereel, limited edition of My Book of Hours, published for the American market, Geneva, 1922

Frans Masereel, limited edition of My Book of Hours, published for the American market, Geneva, 1922A second American reprint wasn’t released until 1971 (Dover Books, New York). Actually, it would take another two decades for Passionate Journey to reach a wider audience, thanks to the paperback editions published by Penguin in New York and City Lights Publishers in San Francisco, in 1988 and 1989. In subsequent years, however, most of Masereel’s woodcut stories were familiar only to a few artists who would emerge as the first graphic novelists. As one critic noted, New York born Eric Drooker’s 1992 debut Flood! A Novel in Pictures was “heavily influenced by the novels of Masereel”. Just like Art Spiegelman and other icons of the graphic novel, Drooker readily acknowledged Frans Masereel as the father of the genre. Austin Kleon, their younger “brother in arts”, speaks fondly of “the Granddaddy of it all and my personal favourite”.

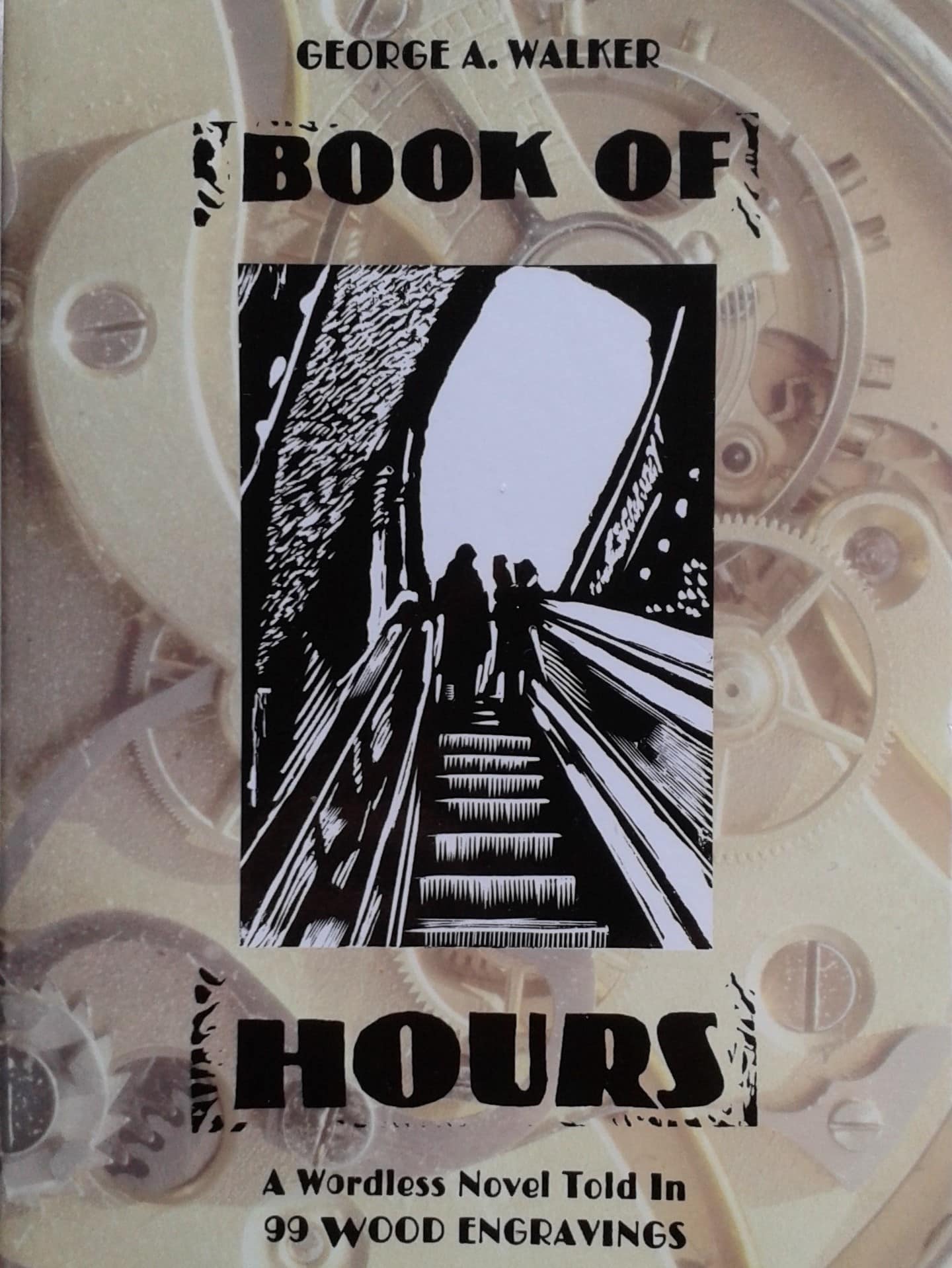

George A. Walker, Book of Hours, 2012

George A. Walker, Book of Hours, 2012In 1981 George A. Walker, then a 21-year-old student at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, visited a ‘Tribute to Masereel’ at the Art Gallery of Ontario, where he first saw Mon livre d’heures. Thirty years later – now one of Canada’s best-known book artists – Walker was inspired by Mon livre d’heures to create his own Book of Hours. A Wordless Novel Told in 99 Wood Engravings, in which with wood engravings – not woodcuts – he captures the tragedy of 9/11, the day that started out like any other Manhattan working day, yet quickly turned into a nightmare.

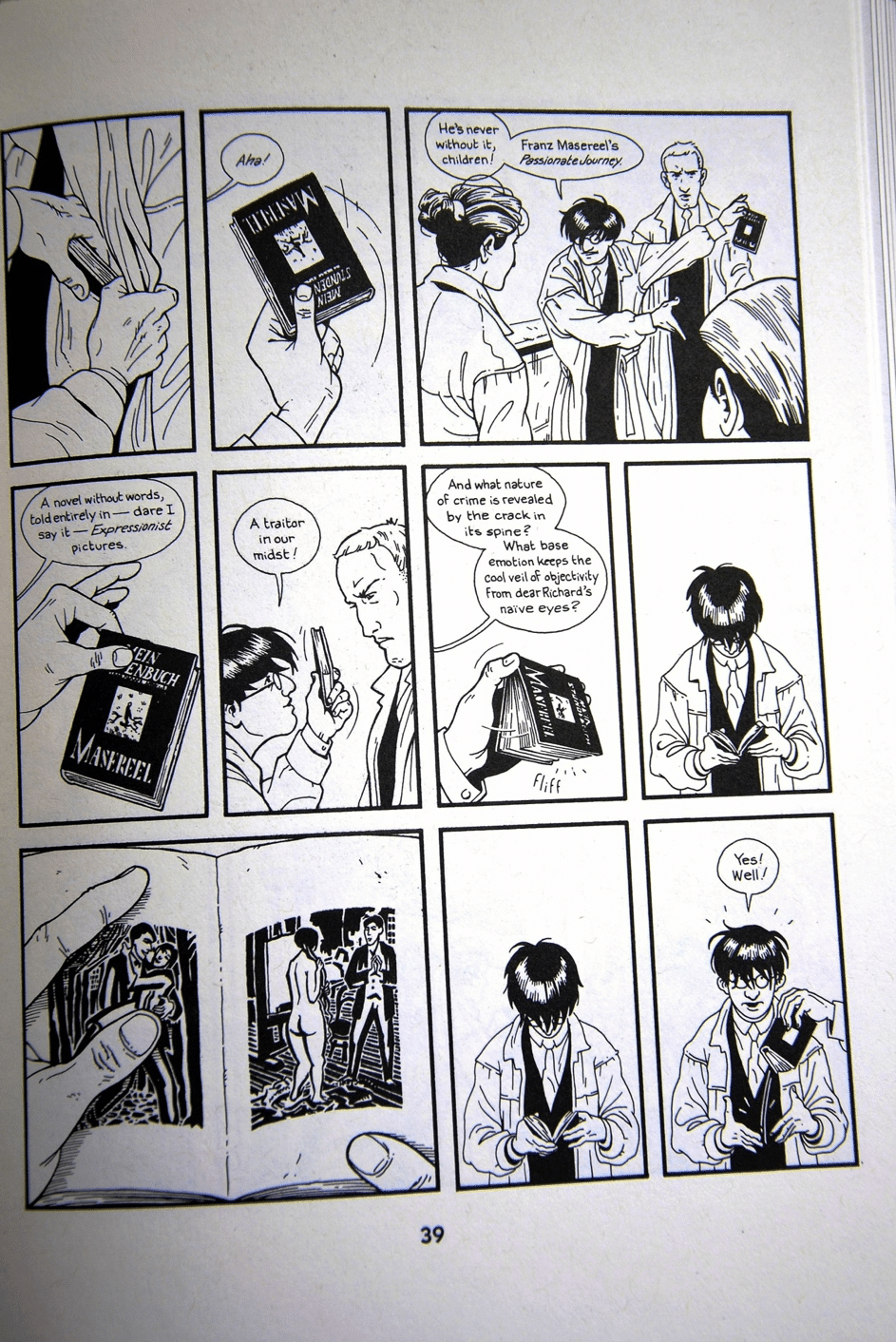

A clear indication of Masereel’s growing fame among New York graphic novelists from the 1990s on is one particular page in Berlin: City of Stones (2000), the first part of the ambitious graphic trilogy Berlin by Jason Lutes (b. 1967), completed in 2018. The story is set in 1928-1929, a period dominated by increasing violent clashes between Nazis and communists. Since the popular edition of Mein Stundenbuch – the German title of Mon livre d’heures – was reprinted multiple times in 1928 and 1929, becoming one of the best selling books in Germany, it’s not that surprising to find in Lutes’ Berlin an emphatic tribute highlighting Masereel’s prominent position as a graphic storyteller at the time. One page in the book is entirely dedicated to a delightful scene in which an art student snatches a copy of Mein Stundenbuch

from the pocket of a fellow student’s rain coat during their heated debate on Expressionism and New Objectivity. Opening the book, he reveals a spread showing two woodcuts Lutes has copied meticulously.

A page from the graphic novel Berlin: City of Stones (2000) by Jason Lutes

A page from the graphic novel Berlin: City of Stones (2000) by Jason LutesIt was art historian David A. Beronä, author of Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels (New York 2008), who introduced a wider American audience to Masereel’s woodcut stories in the first decade of this century. The first chapters of Wordless Books are devoted almost exclusively to Masereel’s wordless novels, and in his introductions to the reprints of Passionate Journey: A Vision in Woodcuts (2007) and The Sun & The Idea & Story Without Words. Three Graphic Novels (2009) Beronä points out where the first generation of American graphic novelists found their earliest inspiration. His findings were affirmed by William Patrick Martin, the editor of the Wonderfully Wordless (2015) anthology, who pointed out the obvious influence of Masereel in the work of Art Spiegelman (b. 1948) and Eric Drooker (b. 1958).

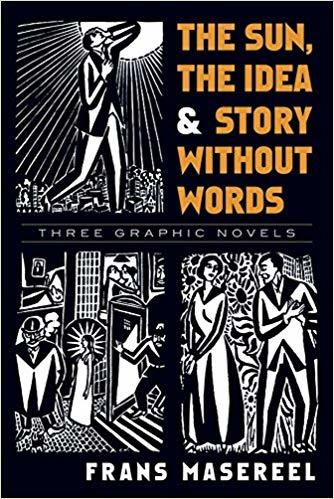

The Sun & The Idea & Story Without Words, Dover Books, New York, 2009

The Sun & The Idea & Story Without Words, Dover Books, New York, 2009In the years following the success of his debut novel Flood! (4th edition 2015) which earned him an American Book Award, Drooker gained additional notoriety with covers he created for the weekly The New Yorker Magazine, and with the illustrations to accompany poems by Allen Ginsberg. In 2013, he toured France and Germany for a few guest lectures, including one at the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Saarbrücken (‘Visiting Professorship Frans Masereel’), cofounded by Masereel shortly after World War II. In an interview with The Comics Journal Drooker recalled how, as a twelve-year-old, he skimmed through copies of Passionate Journey and The City he was given by his grandfather, an independent bookseller. Initially, he wasn’t that impressed – “My short attention span was, no doubt, the result of television”. Some years later though, after the English artist Sue Coe had given him a Masereel anthology, young Drooker got intrigued, and, eventually, obsessed: “I began to feel haunted by these silent books. In my early twenties, I began to study Masereel’s technique, and after Sue Coe gave me a huge anthology of his work, I became possessed by his vision.” Undoubtedly, there was the instant association of the television news reports on the Vietnam war with the brutal anti-war woodcuts Masereel published during World War I in Debout les morts! (Arise Ye Dead, 1917) and subsequent albums:

American painter and graphic novelist Eric Drooker

American painter and graphic novelist Eric Drooker“As I gazed at page after page of intense, black and white art, I was confronted by a startling fact: stories didn’t need any words at all – if the pictures were strong enough. I hadn’t ever been to Europe, at this age my knowledge of history was extremely limited. But I knew from watching television that my country was currently at war in a place called Vietnam. Bombs were dropping every day, every hour, and most of the victims were civilians. None of the adults in my life ever explained to me what the war was about. […] Whenever I turned to Masereel’s picture novels, I saw images of women and children living under unimaginably violent circumstances. I saw images of young men drafted, and sent off to war. […] The fact that I was a New York City kid who didn’t speak a word of French or German didn’t matter a bit. Volumes of history, sociology, psychology, poetry – and the eternal human comedy were communicated to me directly through the language of pictures. Masereel continues to inspire my vision to this present day, as I create new picture stories for the twenty-first century.”

American graphic novelist Art Spiegelman

American graphic novelist Art SpiegelmanArt Spiegelman, ten years Drooker’s senior, became well-known as a graphic novelist with his political satire Maus (1991), which features the Nazis as cats and the Jews as mice. Maus was first published in the 1980s as a comic, and in 1992, it became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize. Just like Drooker, Spiegelman explicitly refers to Masereel’s woodcut stories as his earliest sources of inspiration.

In collaboration with jazz composer and saxophone player Phillip Johnston, he created Wordless!, a combination of lecture, video and live jazz music. The ‘hybrid performance’ introduced the audience to the world of Masereel’s ‘silent novels’ and to the works of graphic novelists who drew inspiration from his wordless stories. Premiered as a lecture at the Sydney Opera House in 2013, Wordless! evolved into a live show, first performed in 2014 at the Miller Theatre of New York’s Columbia University. In 2016 Spiegelman presented Wordless! at London’s Barbican Centre, in 2018 at the Philharmonie de Paris.

When Masereel passed away in 1972, the obituary in The New York Times made no mention of his woodcut novels. It was not until decades later that the captionless woodcut stories he created between 1918 and 1928 were acknowledged as the most significant part of his oeuvre.

The disappearance of the woodcut novel should not come as a surprise. Woodcarving is pure craftsmanship dating back to the Middle Ages. It’s tiring, time-consuming manual labour. It not only requires talent and imagination but also the ability to focus, to be patient, to be precise, and to persevere with more energy than most artists nowadays, spoilt with technical and digital tools, can bring to the table. Will the tablet replace “traditional carving tools, wood blocks and printing presses of the bygone era”, as predicted in 2013 by Paul Trinidad in The Art of the Graphic Novel?

By definition the mere concept should be questionable, as an artist carving wood cannot be equated with someone creating and manipulating virtual imagery. Fortunately, the technique behind creating actual woodcuts is still very much alive today. Trinidad himself produced convincing proof of that as a co-editor of The Art of the Graphic Novel, published by the University of Western Australia and rightly dedicated to “the old masters” Frans Masereel and Lynd Ward. Part 1 contains a superb selection of short woodcut stories created by Australian and American students. To accompany this selection, Trinidad included a revealing quote by Masereel: “The artist is a witness of his time, but he can also be an accuser, a critic, or he can celebrate in his works the uneasy greatness of his day.”