The St Matthew Passion Is About Us

Ever since the St Matthew Passion was first performed in the Netherlands, in 1870, this masterpiece by Johann Sebastian Bach has continued to gain in popularity in the Low Countries. In the Netherlands alone, hundreds of performances of BWV 244 are organised each year around Good Friday. So, why this fascination with a commemorative work that was written almost three hundred years ago?

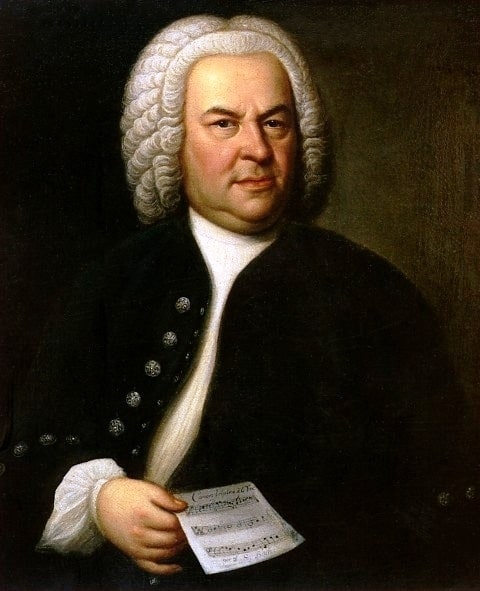

Elias Gottlob Haussmann, Johann Sebastian Bach, 1746

Elias Gottlob Haussmann, Johann Sebastian Bach, 1746It is a remarkable phenomenon. The Internet is our religion, our smartphone the God in whom we meet others. In rapidly-secularizing Europe churches are emptying, and yet more and more people are finding their way to one of the most deeply-rooted religious compositions of all times, Johann Sebastian Bach’s St Matthew Passion.

Indeed, the phenomenon of the passion cult goes further than this one magisterial composition. Other musical passion stories are also regularly performed round Easter time, and each year since 2011 a completely updated version of the passion story, full of (Dutch-language) pop numbers, has reached an audience of millions in the Netherlands. This event, known as The Passion, came over from Manchester. There have been three editions in Flanders, too, where it is called De Passie.

Nowadays there are translations of the St Matthew Passion, arrangements for children and even a version with strong tango influences. However it is performed though – Bach’s version or one of a host of popular artists – the story of the last days of Jesus Christ continues to move and intrigue us.

The development of the passion cult

Thomaskirche, Leipzig

Thomaskirche, Leipzig© Dirk Goldhahn

The first performances of the St Matthew Passion took place in 1727, 1729, 1736 and 1740 in the Thomaskirche (St Thomas Church) in Leipzig, where Bach was the music director at the time. The passion was actually a special composition for the long evening mass on Good Friday. As the music was interspersed with readings and sermons, the service must easily have lasted more than four hours.

After Bach’s death, in 1750, it would take until 11 March 1829 before the work was heard again, and in a shortened version at that, adapted to the taste and customs of the time. It was the young Felix Mendelssohn who put Bach’s music back on the map again with this performance.

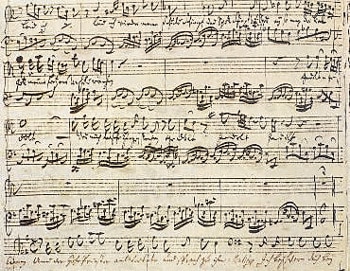

score of St Matthew Passion

score of St Matthew PassionAlmost half a century later, in 1870, the St Matthew Passion was heard for the first time in the Netherlands, with Bargiel conducting the Toonkunst Rotterdam choir. In Amsterdam the concert hall performances with conductor Willem Mengelberg and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra ensured growing interest in the work between 1899 and 1944, while the Nederlandse Bachvereniging has performed the passion every year since 1922 in the Grote Kerk (Great Church) in Naarden. These performances are the cornerstone of the passion cult in the Netherlands and are attended by large numbers of well-known figures and dignitaries.

It is almost impossible now, in 2019, to count how many performances take place in the Netherlands and Flanders. Interest in the work has only increased. That the Netherlands, in particular, should succumb to this piece of music may have to do with its Protestant history, Bach intersperses the gospel with Lutheran choral music, but the presence of musical pioneers in the Netherlands certainly plays an equally large role.

Recognisable story and layered music

The continued success of the St Matthew Passion can be explained in different ways. First of all, there is the fact that the story is so recognisable. Of all the stories in the Bible, the birth and the crucifixion of Jesus are perhaps the best known. Even the majority of non-believers are still familiar with concepts like the Last Supper, Judas Iscariot’s betrayal, the cock crowing and Christ’s journey to the cross. Stories like these form the basis of our Western culture and appeal to the imagination even outside their religious context. In the St Matthew Passion, Bach works with a combination of texts from the Gospel and commentaries, put together by his contemporary, Picander. As a result, the story is not only told, it is actually brought to life in an almost theatrical setting.

A second important element is, of course, the music itself. How does Bach manage to keep the musicians’ and the audience’s attention for three hours or more, depending on the tempos chosen? What is immediately noticeable is the variety of different genres within the passion. There are lyrical arias for the soloists, descriptive recitatives with which the evangelist links the different parts of the story, Lutheran choral music and tumultuous passages for several choirs and orchestral groups. Sometimes Bach’s musical world is grand and impressive, and then it is extremely intimate and fragile. The music is also highly evocative. Bach makes the thunder and lightning almost literally audible, a snake crawls through the staves as a string of notes. The cock crowing is as expressive as Peter’s bitter tears when he realises that he has denied Jesus.

A St Matthew Passion for everyone

The combination of a rich libretto and a fascinating musical universe mean that you can listen at different levels and yet still have an equally strong aesthetic experience. Many contemporary listeners will experience the Lutheran chorales, the best known of which is O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden, as welcome rest points in the complex fabric of Bach’s music. For those who were in the Thomaskirche in Leipzig in 1729, these were the texts and melodies that they knew and sang in church. Between pure musical appreciation of the work and totally lived experience of the substance there are endless gradations between which a listener can switch with the greatest of ease. For some the music itself has an almost religious status, for others the music reinforces the religious power of the Gospel.

In the popular Dutch television programme De wereld draait door, in 2016, conductor Reinbert de Leeuw stressed how full of abundance and meaning every bar of this passion is. Perhaps that is one of the reasons for the endless durability of this work. Every time it is performed, every time one listens to it, new details become apparent. Bach’s partiture is so lavish that even after three centuries it has by no means yielded all its secrets.

So, there is the Bible story and there is the music, but if we see how many contemporary versions are generated by artists’ creativity every year around this period, it is also because the underlying emotions of the story still manage to move a very large part of the population. This story – and certainly Bach and Picander’s version – is about love, grief, regret, disillusionment, frustration, despair, pain, hope, sympathy, joy and sorrow. Those underlying, deeply human feelings are the core of every possible arrangement of the St Matthew Passion and other passion stories. The St Matthew Passion is about us.