How the Struggle Against Water Shaped Dutch Identity

The St Elisabeth Flood, which washed over Zuid-Holland six hundred years ago this month, is one of the most severe inundations ever to affect the Netherlands. In the lively memory culture surrounding that fateful event national pride and a sense of vulnerability go hand in hand. The cultural depiction of later flood disasters also played with those conflicting emotions. A story of water wolves, floating cradles, paternal monarchs and a finger in the dyke.

In the night of 18 to 19 November 1421 a violent storm smashed the dyke around the Grote Waard in Zuid-Holland with disastrous consequences. Several dozen people drowned and the material damage was enormous. In addition, there was an economic disaster: in large parts of the Grote Waard agriculture was no longer feasible. Many inhabitants of what once had been an extremely prosperous region were deprived from one moment to the next of their source of income and

sustenance. This year is the six-hundredth anniversary of this disaster, known as the St Elisabeth Flood.

Master of the St Elisabeth Panels, The St Elisabeth Flood, c.1490-1495, oil on panel

Master of the St Elisabeth Panels, The St Elisabeth Flood, c.1490-1495, oil on panel© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Together with the flood disaster of 1953 the St Elisabeth Flood is among the best-known inundations in Dutch history. They are etched in the collective memory of the Dutch thanks to the lively memory culture: to this day this is kept alive via websites, newspaper articles, children’s books, documentaries, films, paintings, museums and visitor centres.

The national memory culture surrounding both disasters involves a fascinating paradox. On the one hand it evokes traumatic events from the past, which expose the vulnerability of the inhabitants of the Low Countries: all too often they lost the struggle against the elements. On the other hand, both inundations appeal to a national feeling that goes hand in hand with a certain pride.

Workman on the gantry crane during Delta works in the Haringvliet, a former inlet of the North Sea

Workman on the gantry crane during Delta works in the Haringvliet, a former inlet of the North Sea© Anefo/Nationaal Archief

For it is at least as firmly anchored in the collective memory that the Dutch, like no other people, were able to subdue the water thanks to their pioneering spirit, capacity for cooperation and technological innovations. After the 1953 flood disaster the Delta Works were created, which are heralded as a “modern wonder of the world” and gain admiration at home and abroad. And the area that was submerged after the St Elisabeth Flood now attracts thousands of tourists a year because of the innumerable creeks through which you can sail in electric boats. That is a lucrative source of income. In this way the Dutch have after all imposed their will on the water.

Vulnerability and pride, I shall argue, run like a thread through the aquatic history of the Netherlands. These two basic attitudes can also explain why we have come to see the struggle against the water as an important element in the Dutch identity: over the centuries they have given a strong impulse to the national sense of solidarity.

Vulnerability and pride run like a thread through the aquatic history of the Netherlands

For example, the awareness of vulnerability, represented in the eternal threat of the “water wolf”, brought with it the continual necessity to cooperate. In times of disaster a further element was added: the widely shared desire to help one’s fellow countrymen by organising large-scale charity campaigns. Once the crisis had been surmounted, that unleashed a sense of solidarity in turn, but this time in the form of pride: helpers were honoured, kings and queens were celebrated and technical brilliance praised to the skies.

Luctor et Emergo

The cultural media played an important part in the encouragement of feelings of solidarity. After a flood disaster, writers invariably reached for their pens to report on events in the form of poems, sermons, stories, commemorative volumes, songs and plays. In addition, there were visual impressions in the form of prints and painting. Through the endless repetition of clichés there emerged a fixed repertoire of imagery to which writers and artists constantly resorted.

One narrative links all those stories and images. I should like to call it the luctor et emergo narrative. This Latin saying means literally: I struggle and surface again. It dates from before the Dutch Revolt against the Spaniards and came to serve as the motto of Zeeland. Figuratively the motto also refers to the Dutch cultural depiction of flooding. Eventually the central message of writers, journalists and artists became that the Dutch could overcome any disaster, however difficult the circumstances. Solidarity was the key to resilience and recovery. Until the 1960s this appeal to solidarity was mostly motivated in religious terms.

The luctor et emergo narrative took different forms in the cultural imagination: via recurring symbols, role models and the emphasising of solidarity in word and image. Firstly, print-makers and writers make abundant use of symbols that express vulnerability and resilience at the same time. That applies for example to the baby in the cradle. That motif dates back to an altarpiece made in 1490 as a tribute to the warm-hearted charity with which the inhabitants of the town of Dordrecht gave succour to the victims of the St Elisabeth Flood. It now hangs in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam. In the painting there was a scene in which a cat keeps a cradle containing a baby from toppling over. This was recycled in different contexts in subsequent centuries: from poems on the Christmas Flood of 1717 to strip cartoons and films on the flood disaster of 1953. It stood as a symbol for the urge to survival, hope and divine providence – via the Biblical reference to Moses in the basket.

Detail from the altarpiece on the St Elisabeth Flood: a cat keeping a cradle with a baby in it from tipping over

Detail from the altarpiece on the St Elisabeth Flood: a cat keeping a cradle with a baby in it from tipping over© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

A second iconic image is the water wolf. On countless occasions writers and print-makers showed how the Dutch were able to subdue the “water wolf”. In this way they depicted the sea or rivers as a ravenous beast, hungry for land and drowned humans. The seventeenth-century poet Joost van den Vondel described the draining of the Beemster in 1612 under the direction of Jan Adriaanszoon Leeghwater as a victory of the Dutch lion over the cruel water wolf. The draining of the Haarlemmermeer in 1852 was again celebrated as a triumph over the water wolf. Since then the water wolf has become a set concept in the depiction of the struggle against the water. In 2006, for example, André Nuyens published the children’s book De waterwolf on the flood of 1675.

Finger in the Dyke

Thirdly, there was no end of heroic role models. In books for younger readers on the 1953 disaster, brave lads strikingly often played the main part with whom readers could identify. A title like Karel Rescues His Mother speaks volumes – the cover illustration showed what heroism looked like. In a recent strip book by Marc Verhaegen and Jan Kragt, Struggle Against the Water

(2011) we make the acquaintance of the altruistic, muscular Peter, who helps in the emergency services in the Czech Republic and England. Meanwhile we are given a full retrospective view of the flood disaster of 1953 by his father, who is able to rescue his little brother. Giving help – this is the underlying idea – passes from generation to generation. A nice detail is that at a certain moment a cradle comes floating past.

Perhaps the best-known role model is Hansje Brinker, who manages to prevent an inundation by sticking his finger in a hole in the dyke. Thanks to the investigations of Bart Schultz we know that the story derives from a French children’s tale. It became famous thanks to the American novel Hans Brinker, or the Silver Skates (1865) by Mary Mapes Dodges and grew into one of the principal symbols of the Dutch struggle against the water. There is a statue of Hansje Brinker and at present the story counts as a “pre-eminently Dutch adventure”.

Father of the Unfortunate

In 1953 Queen Juliana pays an expected visit to Nieuw-Vossemeer in the disaster area

In 1953 Queen Juliana pays an expected visit to Nieuw-Vossemeer in the disaster area© Anefo/ Nationaal Archief

Besides fictional role models there were other figureheads in the struggle against the water: the Dutch kings and queens. The images of Queen Wilhelmina and Queen Juliana visiting the victims of flood disasters are well-known. Their visit to their stricken subjects projects a feeling of sympathy, involvement and national solidarity.

This traditional image dates back to the beginning of the nineteenth century, when Louis Napoleon, king of Holland (and younger brother of the Emperor Napoleon), paid visits to places hit by disaster. In 1808 and 1809 when there were widespread inundations in Zeeland and the Betuwe, the king went and expressed his sympathy for the victims. He also took positive action by donating large sums of money, setting up a national administration for aid initiatives and investing in water management. His commitment to the population was praised at length in the press and illustrated by print-makers. It earned him the nickname “père des malheureux” (father of the unfortunate).

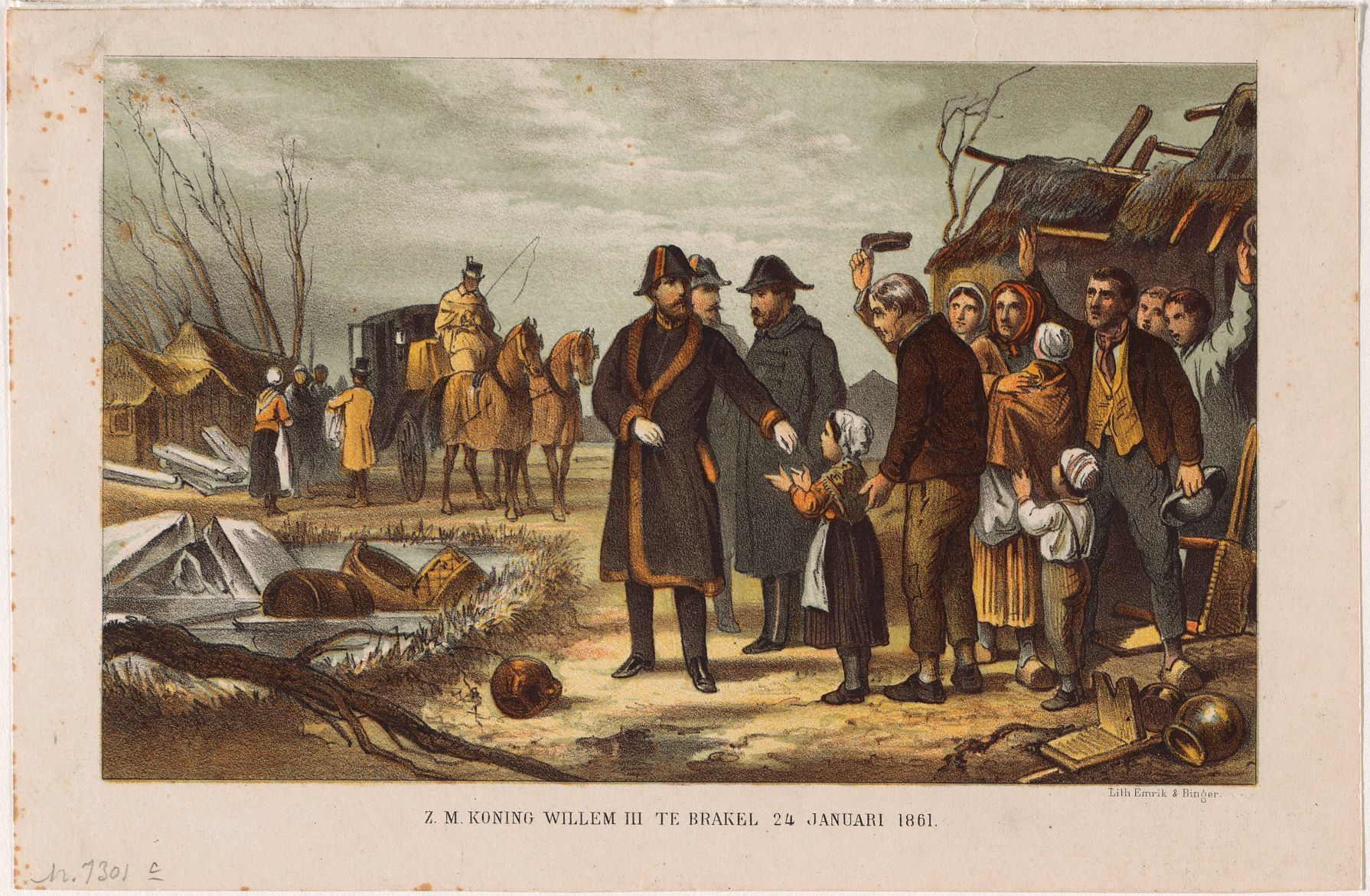

Since that time kings and queens have been all the more aware that they have a task to fulfil in times of disaster: it can even benefit their popularity if they show engagement with the population. Take king Willem III, for example, who cut a prominent figure in the severe inundations of 1855 and 1861 in the delta region. He visited the affected areas, donated large sums of money and coordinated national collections. His commitment was praised in songs, poems and the national press. Print-makers portrayed him as the loving king among his people.

In 1861 King Willem III visits Brakel, which has been inundated. Note the cradle that has been washed ashore

In 1861 King Willem III visits Brakel, which has been inundated. Note the cradle that has been washed ashore© Atlas van Stolk

An iconic example is the image of his visit to Brakel on 24 January 1861, where he is surrounded by grateful villagers. Just in front of him – of all things – a cradle has been washed ashore. In recognition of his commitment he was presented by the Dutch people with a seventeenth-century Bible and in Leeuwen on the Waalband dyke an impressive monument was unveiled. This song summarises the mood very well:

To the hard-hit he’s a friend;

He fears nought, whatever may befall,

In strife he won’t desert us all.

Precious Orange, there you stand,

Long live our King and Fatherland.

Following Louis Napoleon Willem III was also called the “friend of the unfortunate”. In addition, the inextricable link between the House of Orange and the Netherlands was emphasised via the struggle against the water.

Charity

Besides via symbolism and role models the luctor et emergo narrative was also expressed in large-scale charitable campaigns which were initiated. Time and time again the cultural media emphasised that showing charity was a typically Dutch quality, based on Christian mercy. In the course of the eighteenth century charity increasingly assumed regional forms. In 1741, when prominent citizens from Rotterdam and Amsterdam set up a committee to collect money for fellow-countrymen in the east of the country, the town historian Jan Wagenaar praised “traditional Dutch charitableness”.

In the nineteenth century, an explosion of charitable campaigns followed after flood disasters, with columnists urging their compatriots to show their true “national colours”. A virtuous Dutchman should help his fellow-countrymen, was their reasoning. An illustration is the following statement of a poet from 1825:

Thank God that even in this general disaster true Patriotic hearts are found, which have shown through deeds […] that the principal trait in the Dutch character, benevolence, which has survived though all the vagaries of the centuries, still resides here and will reside for as long as this people exists!

Statue of Hansje Brinker in Haarlem, sticking his finger in a hole in the dyke

Statue of Hansje Brinker in Haarlem, sticking his finger in a hole in the dyke© Wikimedia Commons

Again and again an appeal was made to this national virtue, with success. After the floods of 1825, 1855 and 1881 astronomical sums were collected. That trend continued down to the last great disaster in 1995, or better: near-disaster. When the dykes threatened to break in the Delta area, no less than 33 million guilders (almost 15 million euros) was raised during a national television campaign.

No One Was Spared

However powerfully the luctor et emergo narrative manifested itself in the Dutch cultural imagination, writers, print-makers and painters also gave full weight to man’s vulnerability. That disasters caused unspeakable misery and personal suffering was, for example, expressed in the popular genre of flood songs. Part of their function was to spread the news of a disaster. They sketched in great detail how great the losses were. The author of a song from 1825 on the great inundation of Noord-Holland, for example, described how the corpses floated in the water and no one was spared: “Whole families met their graves, Plunged in mourning drear, Down into the waves, Wife and Husband Dear.” No one could resist the power of the water, wrote this poet.

A religious lesson was contained in that vulnerability, since the threatening water expressed in the eyes of most culture-producers in the past the voice of God. Ultimately man’s fate was contained in God’s hand. Anyone wanting to prevent new disasters, must reform his life and especially: pray more. The poet J.W.F. Werumeus Buning put that thought into words in his ‘Ballad of the Flood Disaster’ (1953) as follows:

The sea spares neither men nor land;

A voice sounds, see, the dykes are breaking,

And, mightier than sermon-making,

That voice turns hearts and bowels to sand:

Only when our strength is shaking

Is it clear, all other hope forsaking,

That each of us is in God’s hand.

Pride and Vulnerability

To summarise: in the cultural depiction of the Dutch struggle against the water symbols, role models and the cult of charity contributed to a national feeling of solidarity. Writers, print-makers and illustrators particularly emphasised resilience and the capacity to overcome a disaster: the luctor et emergo

narrative. The report of the progress of the Delta Works was also coloured by national pride: this sample of technical wizardry can still rely on a high notation in the list of historical achievements of which the Dutch are proud.

1986: the Eastern Scheldt Storm Surge Barrier is inaugurated, marking the completion of the Delta Works

1986: the Eastern Scheldt Storm Surge Barrier is inaugurated, marking the completion of the Delta Works© Anefo/ Nationaal Archief

Yet we must not forget that vulnerability and pride are two sides of the same coin. In the age-old imagery the devastating power of the water plays at least as great a role. Not the invincibility, but the puniness and insecurity of human life are the central themes.

Now global and the rise in sea levels form an ever-increasing threat for future generations, vulnerability will have to assume a more prominent place once more in the national narrative. The past shows us how the awareness of vulnerability could act as a seed bed for solidarity.

Further Reading

- Lotte Jensen, Wij tegen het water. Een eeuwenoude strijd (Us Against the Water. An Age-Old Struggle), Vantilt, Nijmegen, 2018, 96 pp.

- Lotte Jensen & Adriaan Duiveman, Welke verhalen vertellen we? Narratieve strategieën rondom waterbeheer and zeespiegelstijging (What Stories Do We Tell? Narrative Strategies Relating to Water Management and Rising Sea-Levels), Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen, 2020, 48 pp.

- Hanneke van Asperen, Marianne Eekhout & Lotte Jensen (ed.), De grote en vreeselijke vloed. De Sint-Elisabethsvloed 1421-2021 (The Great and Terrible Flood. The St Elisabeth Flood 1421-2021), De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam. 208 pp.