The coronavirus pandemic makes this more obvious than ever: despite our constant connection via all kinds of screens, loneliness appears to be a growing problem. How do you discuss this problem? Does it help to give a face to loneliness? In what way? These questions are addressed in the interdisciplinary research project Monáx, of which this essay is a part. Film critic Karin Wolfs talks about laughter, which as a socially desirable phenomenon is the paragon of happiness. But what if that laugh cannot be sustained? An essay about the face of loneliness in the midst of others.

Laugh and the world laughs with you. With that bit of folk wisdom, Penny Fleck raised her son Arthur according to good American tradition. He now makes a living as a clown for hire on the streets of Gotham City. The practice there turns out to be different. As much as Arthur persists in his cheerful act, he encounters nothing but hostility in a dilapidated environment where distrust and aggression reign. It is the strong who rule the roost, and souls like Arthur end up in an alley with the rubbish.

We’re talking about Todd Philips’s Joker, most talked about feature film of 2019, a Hollywood production that surprisingly won the Golden Lion in Venice. Later followed by an Oscar, Golden Globe, and British BAFTA Award for both Joaquin Phoenix’s title role as Arthur Fleck/Joker, and for the cello-heavy, moody musical score by Icelandic composer Hildur Guðnadóttir. But there were also quite a few critics who found the film repulsively cynical and empty, who rejected its violence and macabre tone. Nevertheless, Joker was the third-biggest box office hit in Dutch cinemas in 2019 and was voted the second-best film of that year by the Circle of Dutch Film Journalists. The readers of both de Volkskrant and VPRO Cinema voted it their favourite film.

What makes this controversial, grim film popular with so many critics and with such a wide audience? Probably the face it gave to the recognisable loneliness that has become an inherent part of our lives in today’s performance-oriented consumer society. One that is rarely addressed at a time when optimism and hope seem to have become a mantra not only for success, but for problem-solving as well. Precisely what Joker is agitating against.

A central role in Joker is reserved for ‘the show’: the ideal image being peddled to viewers at home through television. The biggest, most popular smiling face – Murray Franklin, played by Robert de Niro – has a platform on a live comedy show, where he hosts guests daily. Following Murray, Arthur also wants to become a stand-up comedian. Having grown up without a father, he fantasises that Murray will recognize Arthur is special and call him down from the audience to come on stage. Like a good little boy, Arthur will recount how he cares for his mother and how she taught him to always put on a happy face. He does this each day before facing the world.

Because his grief is taboo, that maniacal, compulsive laugh is the only alternative

Back in reality, Arthur sits in front of the mirror in his dingy dressing room with his back arched; he applies his clown makeup and puts on a smile – even though he’s never had a reason to laugh in all his unhappy life. Arthur, depressed, can only laugh or smile in two ways. He can smile by putting his fingers in the corners of his mouth and pulling them up until it hurts, with tears in his eyes, flowing all over his smeared makeup. The other way is just as forced. It’s an uncontrollable, compulsive laugh, which he uses as a shield when insulted or approached aggressively. A laugh so loud that it drowns out the pain underneath. Because his grief is taboo, that maniacal, compulsive laugh is the only alternative.

Joacquin Phoenix as Arthur Fleck in ‘Joker’

Joacquin Phoenix as Arthur Fleck in ‘Joker’Alone, abandoned, and betrayed

The terror of the smile had been seen previously on the face of Olympic figure skater Tonya Harding, in Craig Gillespie’s biopic I, Tonya (2017). Harding was reviled when figures from her entourage eliminated her main competitor by inflicting her with a broken knee. Although Harding has always denied knowing about the plot, the incident made her America’s most hated woman. In the film, a 23-year-old Tonya sits in her dressing room in front of a mirror, just before her performance at the Olympic Games in Lillehammer: alone, abandoned, and betrayed. She applies blush to her pale face, trying to put on the smile required in the arena to hide her despair and tears. The compulsive grimace that rivals her grief makes her loneliness fully visible.

Three years before this, Harding was popular and loved for the first time in her life, when she was the first to perform a triple axel – after years of training herself to death. Until she had made that undeniable achievement, no jury had ever deigned to award her first place. Not because she wasn’t a top skater, but because something wasn’t right with her presentation. Only unofficially does one of the judges admit that she is unfit to represent her country, considering that she lacked a ‘wholesome American family’. Tonya grew up in poverty, as a ‘white trash redneck’; her father had left her mother. Tomboy Tonya didn’t play the part of an ideal, delicate woman. She had a bad mouth and didn’t dress smart enough for the snooty figure skating world – she made her own outfits. What’s more, she divorced her abusive husband not long after getting married. In short, she didn’t belong on the ice rink.

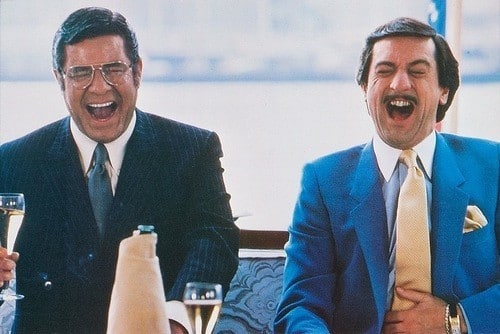

As with Tonya, in Joker, Arthur’s greatest desire is to be seen and gain the recognition that he matters as a human being. Rupert Pupkin – played by a young Robert de Niro – wanted the same in Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982), which served as an important source of inspiration for Joker. Like a groupie, Pupkin obsessively pursues well-known talk show host Jerry Langfield, in the hope to be discovered by him as a new talent. While Rupert says he is ‘in communication’ with Langfield, he actually turns out to be a parcel deliverer in a three-piece suit. Pupkin also wants to become a stand-up comedian and fantasises that he is best friends with talk show host Langfield: he has recreated the show’s stage in his bedroom, rehearses in front of a wall-size photo of a laughing audience, and plays a cassette tape with bursts of laughter.

Jerry Lewis and Robert De Niro in 'The King of Comedy'

Jerry Lewis and Robert De Niro in 'The King of Comedy'Arthur and Rupert have no friends in their everyday lives. They make do by considering the people on television to be their idealised friends. They don’t exist until they are seen and embraced by the crowd because they are unique and special.

If you work hard, anything is possible; that is what these children of the American dream have been taught. The illusion of being able to stand up as a hero and be noticed is the dream fed to them by society so they can make sense of their bland existence. That dream also has a downside. Because a person is assumed to be free to make their own choices, they will also have to pay for the consequences. If success is a choice, then bad luck is your own fault: you should have tried harder. The competition for success divides the world into winners and losers.

Seeing your fellow man as competition is what Jean-Paul Sartre dubbed ‘the American disease’. The more you achieve, the more you are worth. This culture of ambition breeds a narcissism in which you are constantly being asked how you can set yourself apart from others, instead of what you share with them. In this way, deeper human values such as empathy, mutual dependence, and solidarity fade into the background. Vulnerability and inability are approached as problems and made taboo; the ability to establish qualitatively meaningful relationships with others is undermined.

Under those circumstances, it is not surprising that a film like Joker falls on fertile ground, as the embodiment of the sort of loneliness that is felt in the midst of others. The film makes an attempt to smooth out the dialogue concerning this issue. However, making this film a reality was encumbered by the success-oriented production system. In a round-table discussion organised by The Hollywood Reporter, Joker director Todd Phillips explained what a struggle that was. ‘We were in discussion with Warner Brothers for a year, and I would see emails literally saying: ‘Does he realise that we sell Joker pyjamas in department stores?’ So I say: ‘Didn’t movies come first and pyjamas later? Are the films dictated by pyjamas?’

When the smiling mask comes off, the loneliness in the films discussed takes on yet another, more ominous image

Anyone who doesn’t meet the performance standard has something to explain. Anyone found unworthy becomes the warranted object of ridicule and derision. This is what successful businessman and mayoral candidate Thomas Wayne stands for in Joker. When Arthur is brutally assaulted on the subway by three drunken Wall Street investors in suits, shoots, and kills them, Wayne defends the ‘good, decent investors’ on TV and ridicules the ‘cowardly clown hiding behind a mask’: ‘Those of us who made something of our lives will always look at those who haven’t as nothing but clowns.’ It is only from the moment the Joker emerges a criminal in a corrupt world that he is suddenly noticed. Arthur undergoes downhill character development as an antihero: he features in newspaper headlines (‘Killer clown at large’) and gains a following of clown mask wearers who take to the streets to riot against the establishment that patronises them. The smile can no longer be sustained; they revolt. When the smiling mask comes off, the loneliness in the films discussed takes on yet another, more ominous image: that of the index finger held to the side of one’s head, as an imaginary gun or a harbinger of an actual suicide. Because if the loneliness in the show of everyday life is not given a stage, it will claim it, by force. In this way, the taboo flies back like a boomerang to hit society, which ignored it.

Joacquin Phoenix as Arthur Fleck in ‘Joker’

Joacquin Phoenix as Arthur Fleck in ‘Joker’What no one wants to hear

Similarly, in Christine (2016) by Antonio Campos, the protagonist of the same name is weighed down by the straitjacket of the workplace. ‘I feel trapped here’, Christine shouts at her mother, who blames her for putting too much pressure on herself. ‘Those people are destroying me. Why won’t anyone just listen to me?’ When Christine finally understands what the audience is asking of her, she uses her platform to rebel against the exploitation of her dignity. The conscientious reporter works at a local Florida broadcaster, where she creates socially engaged TV segments on issues like budget cuts to health care. But it becomes clear that that isn’t enough. There is a financial crisis, and the ratings have to improve.

Christine is instructed to make juicier segments about misery and violence, because they do well with the viewers. She complies despite her protests, hoping to be noticed by the network boss, who is looking for people for a new, larger channel. But he pays no attention to content, while she becomes miserable because she is forced to sacrifice her ideals. There is no room for the person she wants to be. When the always serious, self-critical Christine finally puts on the desired, phoney smile, it completely embodies her loneliness. Determined, grim, and a tad haughty, she looks into the camera when, after numerous rejections, she for once finally manages to score the opening segment on the daily news show. She uses this opportunity to say what no one wanted to hear. To give her bosses and her audience what they want: her soul.

Christine Chubbuck – because this is a movie based on a true story – committed suicide on live television in 1974. She wrote her own script, the live report of her action, which she read aloud herself: ‘In keeping with the WZRB policy, presenting the most immediate and complete reports of local blood and guts, TV-30 presents what is believed to be a television first. In living colour, an exclusive coverage of an attempted suicide.’ After which she shot herself in the head.

Rebecca Hall as Christine Chubbuck in ‘Christine’

Rebecca Hall as Christine Chubbuck in ‘Christine’Arthur initially plans to do the same in Joker, when he has been abandoned by everything and everyone and has nothing more to lose. His social worker has been sacked due to budget cuts and he himself is without a job when a video recording of one of his stand-up performances gets aired on Murray Franklin’s show. But instead of being embraced as he dreamed, he is mocked and derided. His successful father – who according to his mother is her former boss and mayoral candidate Thomas Wayne – also rejects him, a born loser, claiming that his mother was insane and delusional. Then the show calls Arthur to ask if he would like to come on the show as a guest. He knows that the purpose of the invitation is to present him as eccentric, for the audience’s amusement. He rehearses his grand entrance as the Joker, prepares to steal the show on the spot, but at the crucial moment he aims the gun not at his own head as planned, but at the host of the show: the ideal. Because – as he has now understood – his failed life is not a tragedy that can count on empathy: it is a comedy, a travesty, meant to be ridiculed. Violence is laughter.

Even in that group, which makes the Joker a symbol, the Arthur behind the smile remains lonely and unknown

Arthur says goodbye to his adaptive self, laughs at the pain of rejection, and embraces the chaos: he becomes the Joker, the wry joke that the Waynes of this world have called upon themselves. When Joker laughs back, it’s with a laugh of madness. He laughs at the world that rejected him; an anarchic, satanic laugh. On his way to prison, he is freed from a police car and given a hero’s welcome by anonymous supporters in clown masks who roam the streets. The nihilist who no longer has or aspires to anything is made the unsolicited leader of a movement that seeks to destroy the status quo. But even in that group, which makes the Joker a symbol, the Arthur behind the smile remains lonely and unknown.

We are all clowns

And finally, in the Netflix documentary What Happened, Miss Simone? (2015) we see how the poor black girl Eunice Waymon manages to carve out a place for herself on the stages of white America. She wants to become the first black classical pianist to perform at Carnegie Hall. But because she is denied a place in the world of classical music due to the colour of her skin, in a roundabout way she ends up becoming singer and blues/soul musician Nina Simone. At the same time, the emphasis on her musical talent appears to be a curse: even as a child, that is the only side of her that people want to see. The compulsive focus on her musical talent brings her to dislike her own work. Commercial success, winning prizes, appearances on show after show: it is all empty and meaningless, pretentious and fake.

That all changes when the black civil rights movement gains momentum and she begins to express herself in protest songs: her life takes on meaning. ‘I was needed. I could sing to help my people. That became the most important thing in my life,’ said Simone. She broke the social contract dictating that she had to conform to the existing order and keep her feelings to herself. But because her militant lyrics led to boycotts and damaged her reputation, this also put a dent in her career. She felt punished for who she was. In her diaries, Simone records how for this reason she comes to hate herself and the world, how she languishes in dressing rooms feeling lonely, because ‘you have to pretend you’re happy when you’re sad. They don’t know that I’m already dead.’ After the murder of Martin Luther King, she sings: ‘It comes down to reality, not a performance.’ She turns her back on America for good and leaves for Africa.

In a society that constantly makes us prove our worth, everyone is a lonely caricature

At the end of the 1980s, Simone makes a comeback in Europe, but the woman on stage is damaged. Attallah Shabazz, the eldest daughter of murdered black leader Malcolm X, says in the documentary about Simone: ‘If a person follows their own clock, mind, flow, and if we lived in an environment where we were allowed to be exactly who we are, there wouldn’t be a problem. The challenge is: how do we fit into the world we find ourselves in? Can we really be who we are? Most people are afraid to live as honestly as she did.’

What people like Christine, Tonya, Arthur, and Nina need is not a quick fix feeding them false promises, not hope in fearful days, but recognition as human beings. Therein lies the comfort of films like Christine, Joker, and I, Tonya: that we identify with them when they look their misery in the eye through the mirror. They tell us what kind of world we live in. In a society that constantly makes us prove our worth, everyone is a lonely caricature. Because what’s the point of being better than someone else? Why can’t we do without a stage or applause? Not only did we create the show, the host, and the clown, we also grapple with the consequences. As one of the protest signs in Joker says: ‘We are all clowns.

- This essay is part of Monáx (Ancient Greek μονάξ = alone), an interdisciplinary research project about loneliness with which artist Siba Sahabi and photographer Henri Verhoef (both working in Amsterdam) want to give that feeling a face and thus make it discussable.

- For the accompanying photo series Nexus, Sahabi designed nine abstract masks, which Verhoef photographed with various models.

- The research also consists of a series of articles: the low countries asked three essayists to analyse examples of “personified loneliness”, each from a different angle (film, visual art, literature).

- This project was realised with the support from the Dutch Embassy in Brussels.