‘De zaak Tom’ by Frank Heinen: Patching Up a World Full of Misery

Every month we draw attention to a literary debut which garnered less notice upon release than it deserves. With De zaak Tom (The Tom Affair), sports journalist Frank Heinen has written a novel about an altruistic relationship that isn’t always seen as such. In subtle ways he lays bare the state of the care system in contemporary society as well as the role played by the media in how we perceive certain events.

Sports journalists (or former sport correspondents) who turn to literature are not uncommon in the Netherlands. The most well-known figure is perhaps Bert Wagendorp who started out as a sports journalist, then became a correspondent and columnist for de Volkskrant newspaper, while also being known for novels such as Ventoux (2013, which was filmed in 2015), and Masser Brock (2017). But others too, for example Edwin Winkels and Marcel van Rosmalen, produce a combination of sports writing and prose fiction.

Frank Heinen

Frank HeinenIndeed, Dutch newspapers and weeklies have a long-standing tradition of excellent sports writers, while in Flanders, sports journalism is most often seen as second-rate. In the Netherlands we may find elegantly penned columns in the sports pages, in addition to literary sports magazines like Hard Gras, Santos or De Muur. Flanders is fortunate to have the Bahamontes cycling periodical, but Puskas, a comparable football journal from the same publisher, didn’t last beyond the first five issues.

Thought-provoking observations

Frank Heinen (b. 1985) is one of those excellent sports writers who is well known on both sides of the Dutch-Flemish border. In the Netherlands in particular he made his name as collaborator to de Volkskrant, Hard Gras, De Muur, Revisor en HP/De Tijd. Flemish newspaper readers will know him from his intermittent columns for De Morgen.

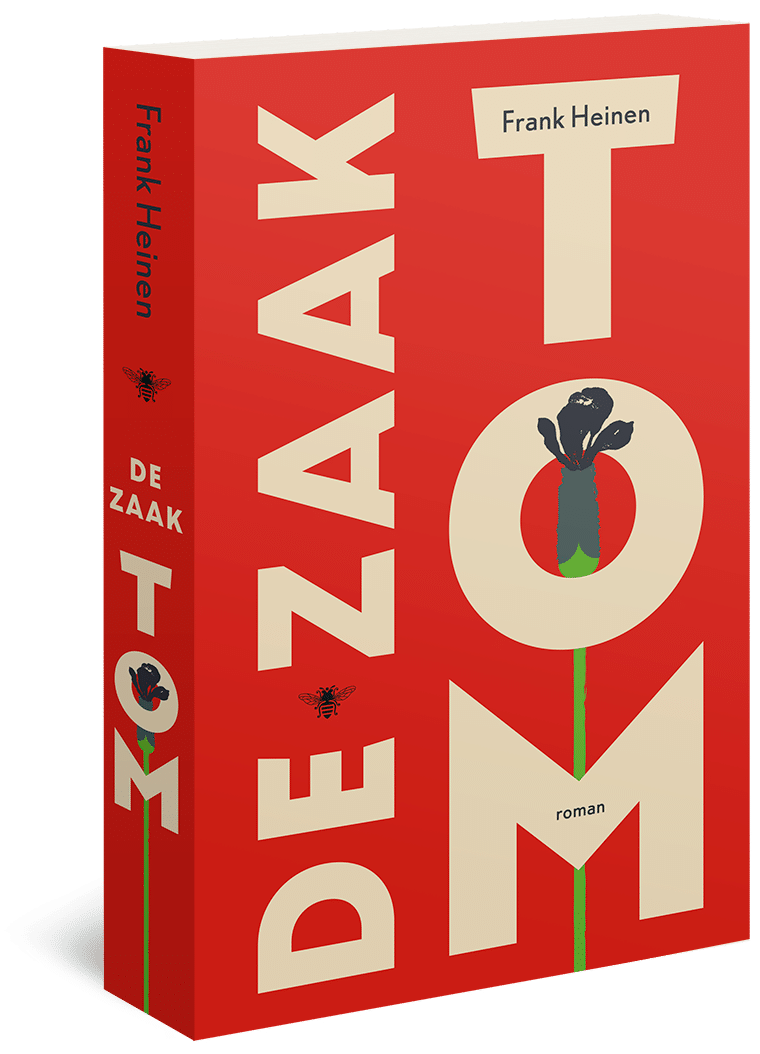

The clear and sometimes original and thought-provoking observations in his sports stories can also be found in his debut novel, De zaak Tom (The Tom Affair), which appeared in early 2019, with De Bezige Bij. In this novel we meet Bob, who on the first page takes his brother Tom with him away from the institution in which Tom is staying. Tom is deaf and wheelchair-bound, and we don’t really know whether he is happy to be taken away, but Bob remains cheerful in the face of all practical complications. ‘Aren’t we having a good time,’ is how he describes their companionship.

‘De zaak Tom’ is a remarkable mix of road trip novel, critique of today’s care system, and media criticism

What follows is a clever story, sometimes funny, sometimes thrilling. Bob seems to think that nothing is amiss, but then finds out that he is wanted for Tom’s kidnap, from Nina, who works at the reference desk in the library where he spends his mornings. Next, all three set off together, and in the course of their journey they are joined by a “gypsy” with a little dog, who claims to be a Tunisian politician on the run.

Bob continually tries to keep Tom and the others happy, while also sowing doubt about his true intentions. Is he really the altruistic brother he claims to be or is he doing all this mostly for himself? At night he whispers to Tom: ‘Don’t believe anyone who says that he’s there for you, kid. People are there and that’s it. Another person can only patch you up for an instant, but that’s all, really.’

Meanwhile the country is riven by debate about the case of Tom. The contemporary zeitgeist leaves little room for nuance, polarisation is at an all-time high. For some, Bob is a terrible monster, a madman who kidnaps and abuses a defenceless patient. For others he is a hero who has liberated Tom from an inhuman system, a luxurious jail where people are no more than a number on a balance sheet. And of course the media are taking the discussion to extremes, as they milk the story for all it’s worth. Eventually this leads to a special and chaotic unfolding.

All this turns De zaak Tom into a remarkable mix of road trip novel, critique of today’s care system, and media criticism and above all makes it an intriguing book about what drives us as human beings. Frank Heinen achieves this with his surefire sentences, in hard-hitting, sometimes funny observations. Fortunately, he doesn’t come to a single, unambiguous conclusion. For, even if everybody always has a reason for doing something, those reasons aren’t always immediately clear to everyone else. And sometimes they aren’t even clear to ourselves.

Two excerpts from De zaak Tom, as translated by Paul Vincent

1st

excerpt – pages 65 and 66 – A morning during the flight…

The next morning Nina is still sitting in the same spot where he left her the night before. Surrounded by truckers and commercial travellers, she is eating a cracker topped with cheese and apple syrup.

Outside, cases rattle across the paving stones of the entrance. Amid all that functionality Nina chews her cracker and reads a book. She exudes a calm that makes him uneasy. Whenever a page has to be turned, her eyes detach themselves from the page and wander briefly through the room. Sometimes her gaze follows a person walking past, and then is caught by something outside his field of vision. Whenever her concentration lapses, the chewing gradually comes to a halt.

He doesn’t know anyone who eats as slowly as she does.

‘Kann ich Ihnen helfen?’

The girl in reception is hanging over her counter. She holds her head to one side. He has no difficulty in not looking down her blouse, which is hanging open.

‘Nein, danke.’

She smiles. ‘Alles nach Ihrem Wunsch?’

Suddenly he wonders whether she perhaps knows something, this girl in reception. He knows enough of what happens on the internet to realise that what he is doing is being discussed. Everything is discussed. And moreover: people are simply fascinated by eccentric types, by men who are washed up on an English beach, say nothing and draw a piano in the sand. Fairy-tale figures. Fascination is lack of understanding for people who think they understand everything.

He can explain it all, in such detail that even this girl will understand, but nobody is crying out for detailed explanations. Understanding is the end of fascination and that’s no good to anyone.

He nods, coughs and goes into the dining room.

2nd

excerpt – pages 133-134: Bob, Tom, Nina and the Tunisian Mehdi have been joined by the journalist Jonas, who wants to write a piece about them. They take refuge together in a chalet in a holiday park.

Later Tom sits at the window with the dog on his lap, following a light aircraft circling the park. Nina is telephoning on her new prepaid phone from the Austrian electronics store on the paving stones by the back door and Bob asks Jonas: ‘How long are you staying actually?’

Jonas holds his chin above his coffee, closes his eyes, sniffs and says: ‘Bit sour.’

For a moment he seems to be somewhere else. Then he says: ‘I have the reputation of being a terrier.’ He fishes something out of his glass with his spoon. ‘When I get my teeth into a piece, I never let go. I hold on, I stand my ground, that’s my quality. One of my qualities. I’m here when I could be anywhere. The world’s on fire, as you no doubt know.’

Jonas constantly uses that expression. Perhaps all promising journalists juggle as flippantly with big words, perhaps Jonas’ promise resides in that flippancy.

Something descends in Bob that he does not immediately recognise. It takes a couple of seconds before he knows what it is: the pain is back. This time it spreads via his side in the direction of his lower abdomen and back. Immediately everything is nothing but pain, it takes him over from inside and gnaws its way out. Everything moves, turns. The walls move apart, time stretches into one endless second. The world turns, shivers and stabs.

The next moment he is not there for a second. He does not collapse. It is more a sort of crash. Nina’s screams, through the kitchen door, sound like the alarm of a car that is parked a little way off.

Frank Heinen, De Zaak Tom, De Bezige Bij, Amsterdam, 2019, 288 pp.