The Ultra-Fine Pen of Visual Story-Teller Ludwig Volbeda

Since Ludwig Volbeda debuted with his fine pen drawings in Hoe Tortot zijn vissenhart verloor (How Tortot Lost His Fish’s Heart), he has been regarded as a spectacular newcomer in the Flemish and Dutch illustration world. Rightly so, because book after book, this young artistic talent knows how to surprise.

Ludwig Volbeda

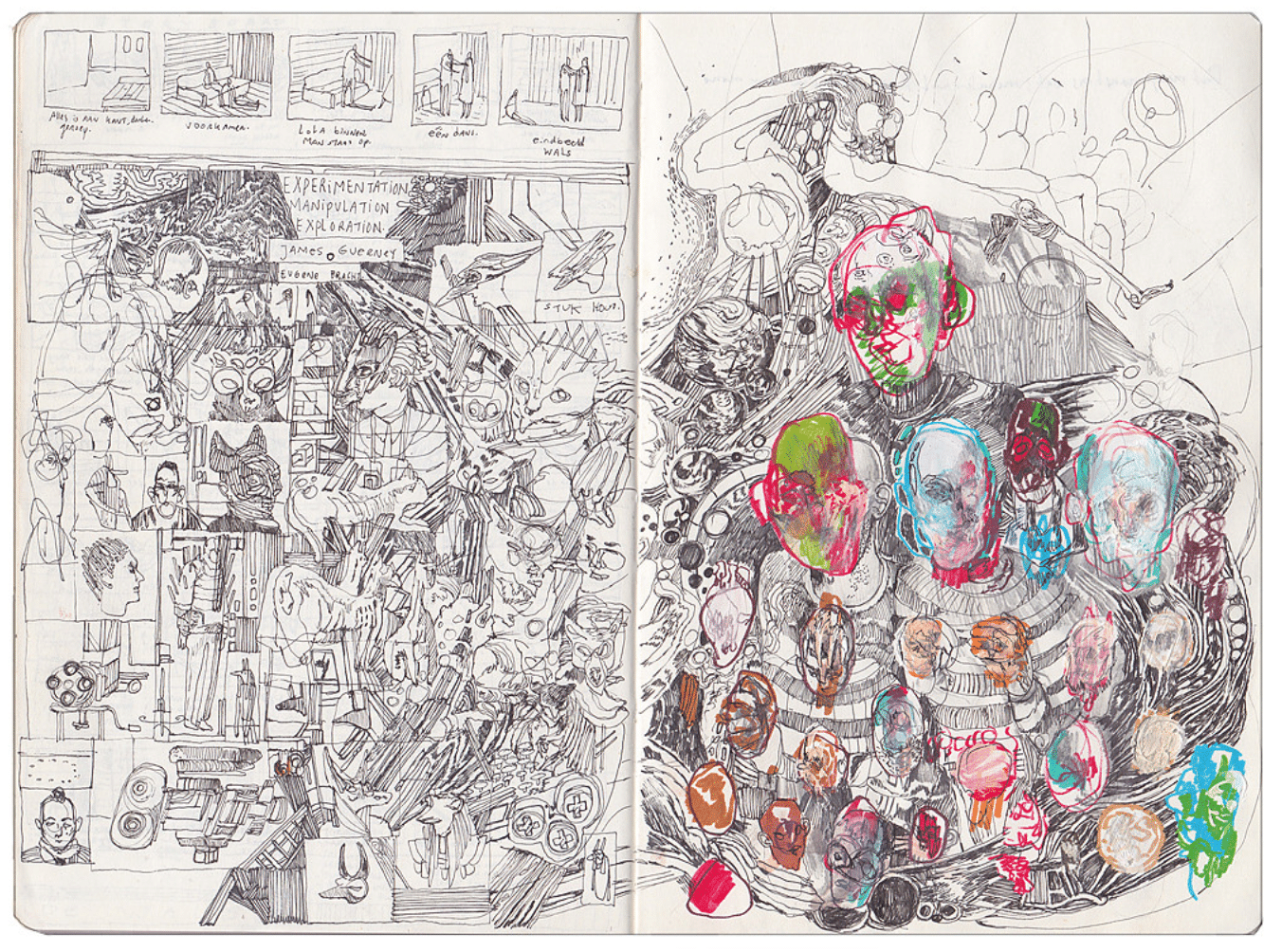

Ludwig VolbedaA wall opposite his work table in Amsterdam holds black, tiny notebooks; as he previously confessed in several interviews, illustrator Ludwig Volbeda (b. 1990) cannot work without them. That wall is covered with endless scribbles, sketches, and cartoons. The tiny notebooks are also jam-packed with drawings and texts. They reflect Volbeda’s unceasing, associative stream of thoughts and serve as the breeding ground for everything he makes: his autonomous (drawing) work, his stories for comic magazine Aline, and his commissioned (book) illustrations.

The first time the children’s book world in the Netherlands and Flanders became acquainted with Volbeda was in 2016. The extremely refined black and white pen drawings that he made for Hoe Tortot zijn vissenhart verloor (How Tortot Lost His Fish’s Heart), Benny Lindelauf’s universally acclaimed picaresque novel about the idiocy of war and the healing power of the imagination, immediately caught the eye: not only because of their authenticity and high quality, but especially because of their strong interaction with Lindelauf’s stimulating, slightly ludicrous, text.

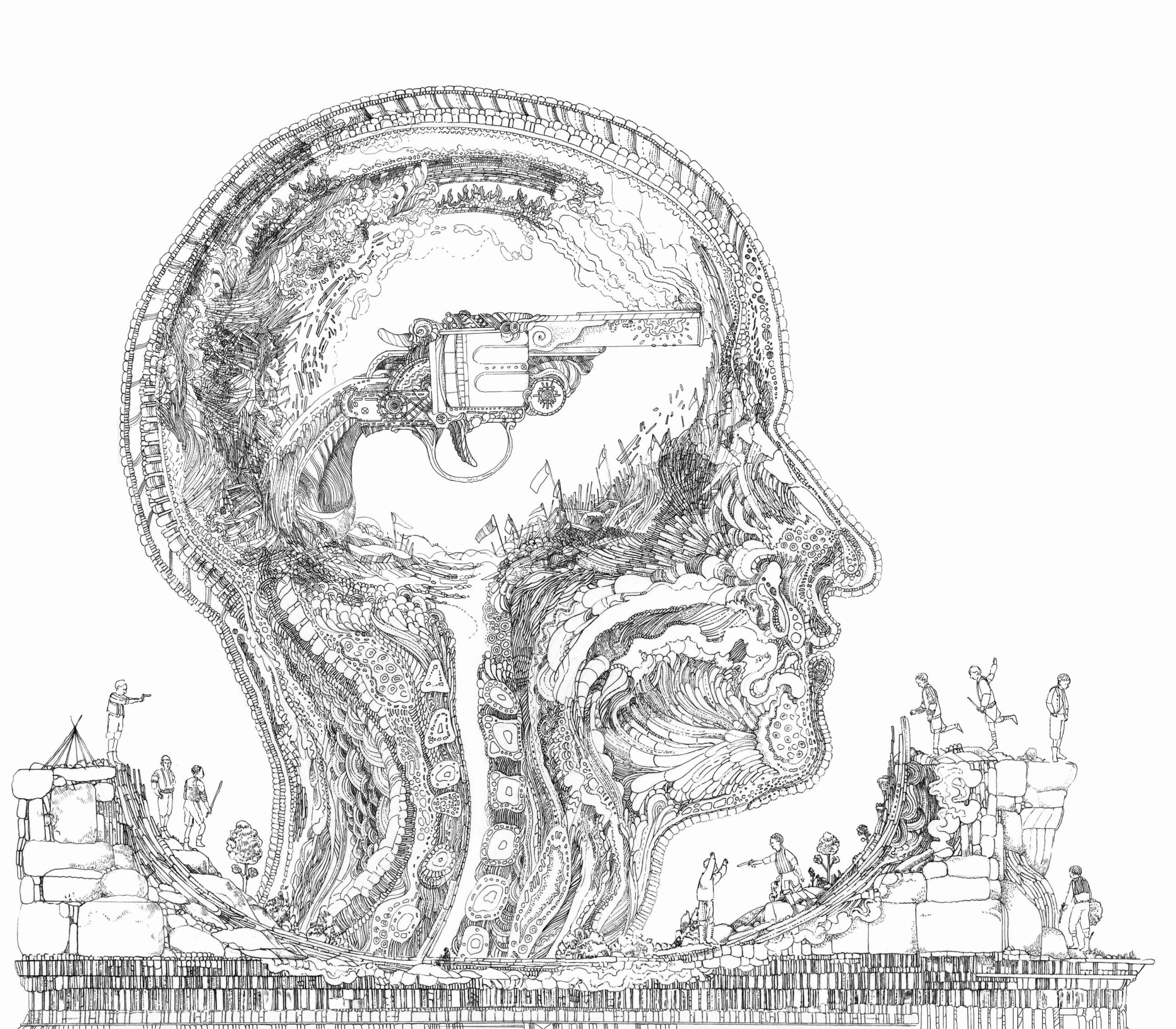

llustration taken from 'Hoe Tortot zijn vissenhart verloor' (How Tortot Lost His Fish’s Heart), Querido, Amsterdam, 2016

llustration taken from 'Hoe Tortot zijn vissenhart verloor' (How Tortot Lost His Fish’s Heart), Querido, Amsterdam, 2016© Ludwig Volbeda

When the latter characterizes the bellicose ‘Imperial Emperors’ as jealous, selfish, power-mad individuals who hunt down soldiers and civilians at random, the next page shows, for example, a spread of a world map in the form of two majestic heads surrounded by landscapes, coats of arms, and celestial bodies in extremely fine lines, which reflect the delusions of grandeur and power struggle of the two both subtlety and significantly. The same tantalizing ambiguity can also be found in the illustration of a cross-section of a head, where the brains are replaced by a pistol: the story of the ‘sons’ recruiter’ who recruits young boys for the army under the motto ‘war is in every boy’s head’ cleverly emphasizes its tragic absurdity.

The detailed, delicate way of illustrating is unmistakably his trademark.

Reviewers unanimously praised Volbeda, who graduated cum laude from St. Joost School of Art & Design in Breda, and was quickly dubbed as ‘spectacular newcomer.’ They praised his “visual shrewdness in his full-page search plates,” as well as his “unique line delivery that shows tremendous control and eye for detail.” This detailed, delicate way of illustrating, for which Volbeda prefers to use an ultra-fine pen (fineliner 0.03 point), is unmistakably his trademark. This way he can tell stories, which is what he ultimately likes doing best.

Sketchbook by Ludwig Volbeda

Sketchbook by Ludwig Volbeda© Ludwig Volbeda

It is no coincidence that, in his own words, he is usually primarily inspired by the interplay that written text and images (can) produce. Besides the French comic book author Jean-Jacques Sempé, known for the Petit-Nicolas books, and the South African artist William Kentridge, whose multifaceted oeuvre revolves around ambiguous observations of and reflections on the world, it is not without reason that Shaun Tan is one of Volbeda’s great examples. In the same way as this acclaimed Australian artist, Volbeda also strives for the ultimate balance between text and visuals in such a way that one can speak of completely autonomous work, in the form of a children’s book.

Illustration taken from '99 voortekens' (99 Omens)

Illustration taken from '99 voortekens' (99 Omens)© Ludwig Volbeda

Exemplary for Volbeda’s narrative prowess is his contribution to the very first issues of Aline, a mix between an art and comics magazine launched in late 2019, which provides a platform for a group of committed young and old cartoonists and illustrators who offer their views on current events based on a theme. In the first issue titled ‘Beyond Civilization,’ where the focus was supposed to be on doomed visions, Volbeda surprised with his dystopian graphic novel 99 voortekens (99 Omens, drawings about “doom”), consisting of collage-like pages composed of loose, understated pen drawings with appropriate poetic phrases. They sound like: ‘the river was dry,’ ‘black butterflies flew in,’ ‘the moon came closer,’ and ‘the children drew the sun bigger and bigger,’ strikingly depicted on an all-yellow background with no outlines. These austere texts cleverly evoke an ominous atmosphere. At the same time, the reader/viewer is given full scope for their own interpretation.

True artist

All these different artistic sides of Volbeda – his narrative style, refined line work, tendency towards comic book-like drawings, and imaginative visual language – come together in his first picture book De Vogels (The Birds, 2016), which he made together with poet, illustrator, and graphic designer Ted van Lieshout. For Volbeda, working with Van Lieshout meant overcoming his shyness to use color; in addition to being a great illustrator, Volbeda also turned out to be a true artist.

Van Lieshout wrote De Vogels on the occasion of the exhibition Van Rodin tot Bourgeois: sculptuur in de twintigste eeuw (From Rodin to Bourgeois: Sculpture in the 20th century). The story is about two statues that are hopelessly in love; he is placed on the square, she is put in the park, both fatally stuck in their stone pedestals. “Two statues are looking at each other. They cannot reach each other,” says van Lieshout, who, as is fitting for a good picture book, is economical with her word choice and whose beautiful sentences appeal mainly to your imagination: “The city is tired. / Think away the traffic/ and you hear only the wind in the trees/ and the birds high in the sky. / They fly off and on, off and on. / Where to? Where from?” Importantly, Van Lieshout’s literary minimalism creates all the space for Volbeda, who, varying in his compositions – sometimes opting for dynamism and a lot of detail, and sometimes just for emptiness and stillness – shows what visual storytelling is capable of.

Illustration taken from 'De Vogels' (The Birds), Leopold, 2016

Illustration taken from 'De Vogels' (The Birds), Leopold, 2016© Ludwig Volbeda

It starts with a textless spread of an incredibly detailed city from a bird’s eye view, with rigidly drawn buildings in black and white, only a few carefully painted green strokes of trees, and in the centre, the pitiful statues. Above them swarm the birds of the title, inventively depicted by Volbeda as wildly rolling waves of multicoloured dots and dashes. They fly, as the comic strip-like pages reveal, a little further on, like messengers of love, back and forth between the images tormented by love: “He still loves you/ She still loves you,” reads the message wrapped in bird poop, (how do you even come up with something like that?). The unusual way in which Volbeda finally allows the lifeless lovers to literally and figuratively merge with each other in an abstract, bursting, powerful, and fiery colour explosion in all shades of red, yellow, and orange is as impressive as it is clever.

De Vogels earned Volbeda acclaim as he became the first Dutchman to win the internationally prestigious Grand Prix of the Biennial of Illustrations Bratislava. The jury praised Volbeda’s unique use of traditional illustration techniques with which he creates an imaginative dreamlike story world, where every print evokes its own atmosphere. And the acclaim didn’t stop with this award. In 2018, Volbeda received the in the Netherlands-highly coveted Golden Brush (Gouden Penseel) as one of the youngest winners ever. He received the award of best-illustrated children’s book for his prints in Fabeldieren

(Magical creatures), a bestiary about legendary and mythical beasts that he made together with Floortje Zwigtman. According to the Golden Brush jury, Volbeda received the award because of his ability to ‘make every animal a credible creature’ in illustrations with ‘a power and depth in colour that you rarely see.’

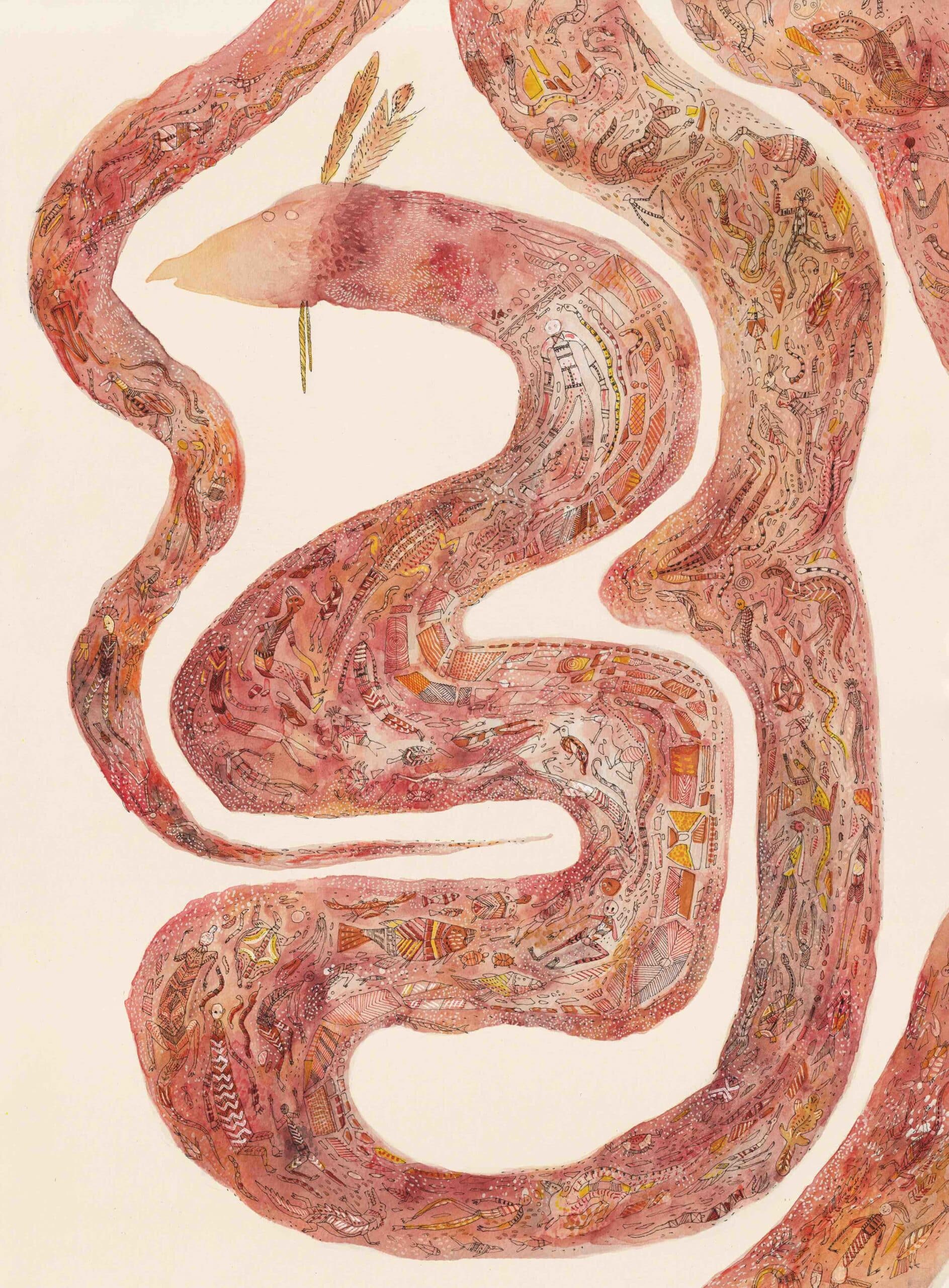

Illustrations taken from 'Fabeldieren' (Magical Creatures), Lannoo, 2017

Illustrations taken from 'Fabeldieren' (Magical Creatures), Lannoo, 2017© Ludwig Volbeda

Those who want to understand what the judges mean, only need to have a look at the beautifully elaborate, impressive dragon’s head in rusty brown, black-grey, and greenish shades on the cover; the Australian reddish-brown rainbow snake in which, as the ‘mother of all life,’ there is a whole story to discover; or the visually rich spread that depicts the parade of the Japanese Yokai. The black-and-white pen drawings of the Japanese houses, like the city in De Vogels, are again produced with an unlikely eye for detail. In the meantime, a wondrous procession of creatures painted in sober pastel shades moves through the street. Above them, the evening sky turns pale pink, effectively underlining the mysterious nature of the Yokai. What also stands out in Fabeldieren is Volbeda’s sense of subtle humour: If you look closely, you will see, for example, the head of Donald Trump among the troll heads.

‘The rumble of war continued’

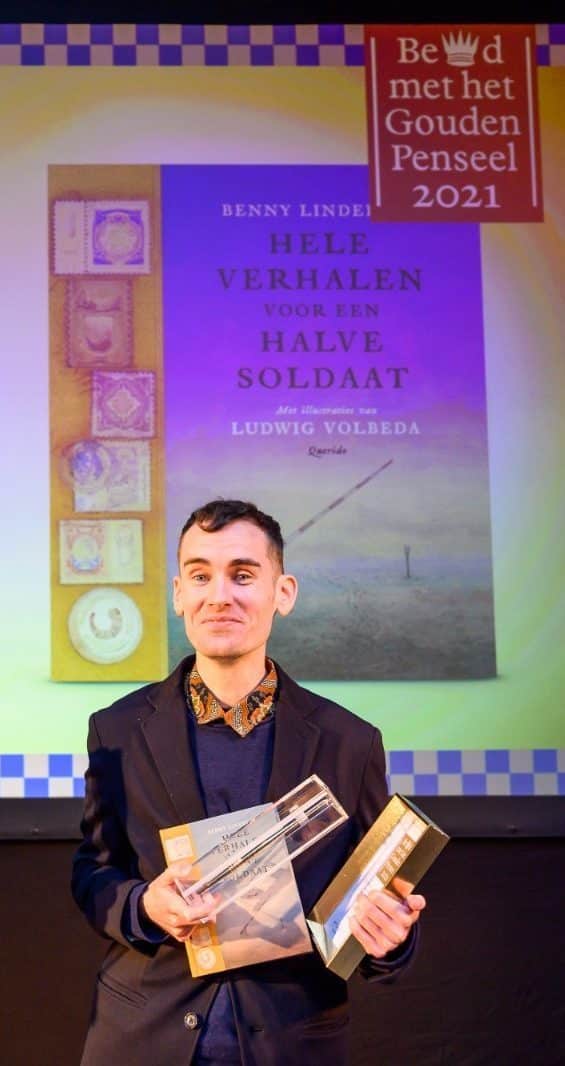

In 2021, Volbeda again won the Golden Brush. This time he received the award for the illustrations in ‘Hele verhalen voor een halve soldaat (Whole Stories for Half a Soldier), a book by Benny Lindelauf. This book takes Volbeda back to the (war) world we know from Hoe Torto zijn vissenhart verloor. For Benny Lindelaufs, Hele verhalen voor een halve soldaat is a great frame narrative about storytelling as an art of survival in wartime. With the motto ‘no better medicine against the horrors of the world than the horrors of the imagination,’ he made illustrations that are just as mysterious as Lindelauf’s individual stories.

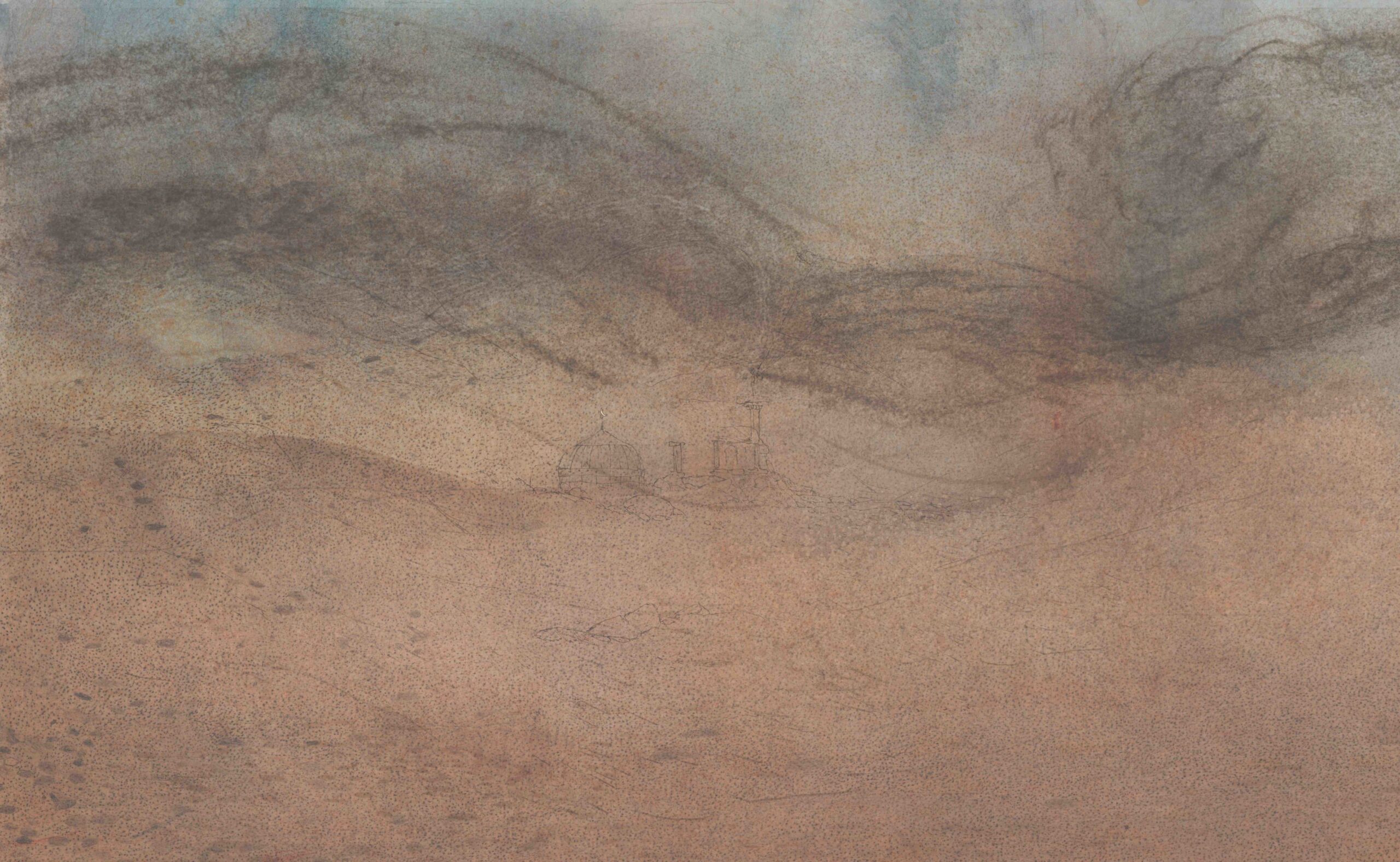

Illustration taken from 'Hele verhalen voor een halve soldaat' (Whole Stories for Half a Soldier), Querido, Amsterdam, 2020

Illustration taken from 'Hele verhalen voor een halve soldaat' (Whole Stories for Half a Soldier), Querido, Amsterdam, 2020© Ludwig Volbeda

But the detailed drawings we know from Volbeda can still be found, such as the spread of an antique cabinet filled with sculptures, and all the drawings of scribbled letters and stamped envelopes that will never reach the home front from the warzone. With his beautiful, suggestive, and desolate landscape prints in sepia tones, Volbeda shows an entirely new side of himself and manages to capture the hopelessness of war very aptly. The desolation of the almost tangible sandy, dusty desert prints, on which only vague images can be discerned, is great. Moreover, the atmosphere is downright ominous, with first a closed and then an open barrier, behind which you see a trail of footsteps disappearing into the distance: “The rumble of the war continues,” is, not entirely coincidentally, the final sentence of Lindelauf’s story.

Despite his entirely unique handwriting, how Ludwig Volbeda will develop further is impossible to predict. But perhaps that is precisely the characteristic of a seemingly inexhaustible artistic talent.