It is well known that the great European powers were involved in slavery. But that the Southern Netherlands were also heavily invested in the slave trade is much less known. In the late eighteenth century, various ships departed from hotspot Ostend to the coasts of West and Central Africa to exchange goods for people. The number of enslaved people on Ostend ships is most likely in the thousands. But to get a good idea of this, a thorough study is needed, writes historian Stan Pannier. He conducts research into this period at the Flanders Marine Institute.

‘The coasts of Africa are also visited by the ships [of the Southern Netherlands], and the Flemings engage there in the same odious trade that other European countries have practised for so long without conscience.’ Today, it is all but forgotten, but the participation of the “Belgian” traders in the slave trade during the early 1780s was by no means a secret to James Shaw, an English tourist of the period.

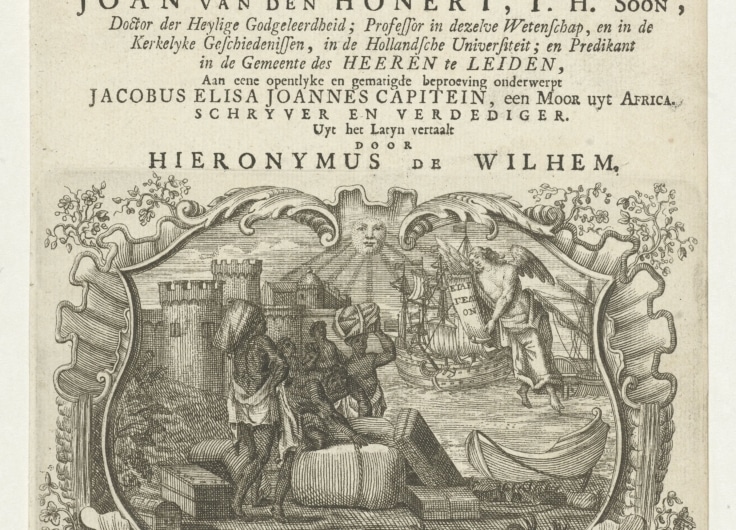

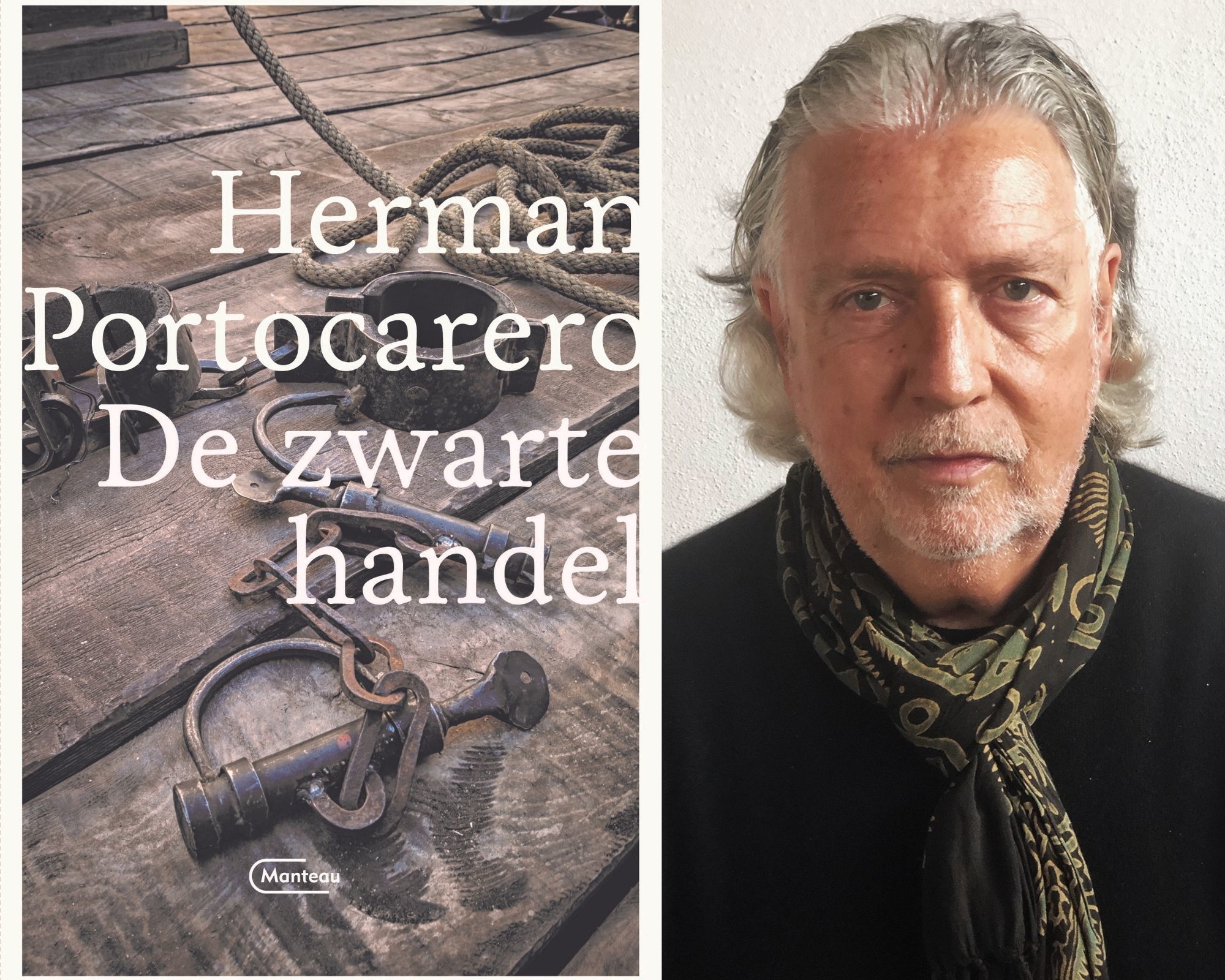

In his recent book De Zwarte Handel (The Black Trade, 2021), Herman Portocarero rightly reemphasizes this piece of history. But many questions remain. In De Zwarte Handel, Portocarero combats the notion that slavery is a closed chapter of history. Following a journey through time and space, interspersed with experiences from his forty-year career as a diplomat, the author argues with good reason that today’s structural racism is a direct legacy of the transatlantic slave trade. Another merit of Portocarero is that he highlights the participation of Belgian traders and capitals in this triangular trade.

In this paper, I further develop Portocarero’s first starting point in De Zwarte Handel about the Belgian involvement, and formulate research questions for the future.

Ostend taken aback

In 1775, the dormant conflict between Britain and her North American colonies escalated. Under the motto “the enemy of my enemy is my friend,” many countries supported the American insurgents and became embroiled in the conflict. In 1778 France interfered, in 1779 Spain followed, and with the Dutch Republic joining in 1780, all of Western Europe was at war with London. All of Western Europe? No. One coastal strip of sixty kilometres in the middle managed to stay out of the clash of arms: that of the Southern Netherlands.

After being part of the Spanish empire for more than a century, the Southern Netherlands passed to the Austrian branch of the Habsburg family in 1714. Vienna’s focus during the eighteenth century was on Central Europe and its competition with Prussia and Russia. It therefore had little to gain from active participation in the conflict between the Western European powers. Together with some other countries, the Habsburgs thus chose to join the so-called League of Armed Neutrality in order to protect their maritime trade from the conditions of war.

In an attempt to stimulate trade even more, Emperor Joseph II proclaimed the city a free port

Indeed, earlier than on the European mainland, Britain, France, Spain, and the Republic fought out their differences at sea. This adversely affected economic traffic. Warships were allowed to seize enemy vessels as much as they wanted, and admiralties also gave private boat owners permission to hunt for trading prey. So how could merchants continue their businesses somewhat safely during war years? Many tried to protect themselves from the supreme British fleet by operating a neutral port or sailing under a safe flag. It was no wonder then that the very best of the European trade would begin to congregate in Ostend from 1778 onwards. In an attempt to stimulate trade even more, Emperor Joseph II proclaimed the city a free port during a festive visit.

Map of Ostend with cityscape, made by Matthaeus Seutter (III) in the first half of the eighteenth century, shortly before heyday

Map of Ostend with cityscape, made by Matthaeus Seutter (III) in the first half of the eighteenth century, shortly before heyday© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

It worked. Better, in fact: it was overwhelming. A different language was suddenly heard on every street corner, the local bricklayers couldn’t get their hands on the bricks, and the prices of existing houses skyrocketed. The army was deployed to demolish the city walls and make way for new buildings. For a while, Ostend became the city that never sleeps. ‘Since I have been here, I have not been able to lay down my work before one o’clock in the morning,’ wrote an employee in one of the commercial offices, ‘and yesterday it was even half past two.’ Night watchmen were appointed to keep the peace in the once sleepy port city.

For a while, Ostend became the city that never sleeps

While in 1770 four hundred ships still arrived in Ostend, in 1780 there were suddenly one thousand. One year later that number had already been doubled. And even more ancient records were broken: according to chronicler Jacobus Bowens, on 11 March 1780 alone no less than fifty-two ships sailed out of the harbour. ‘You cannot possibly imagine a more beautiful scene,’ is how one merchant lyrically described the event to a customer in the countryside.

King of the Congo

In that feverish atmosphere of ever more and ever greater, things also went ever further. Foreign traders brought international trade routes with them, but local firms also dared to look beyond the horizon. If sailing to the Mediterranean had been quite exotic in the past, Flemish sailors could now be made fun of by their colleagues if they had not yet crossed the Atlantic, Bowens describes.

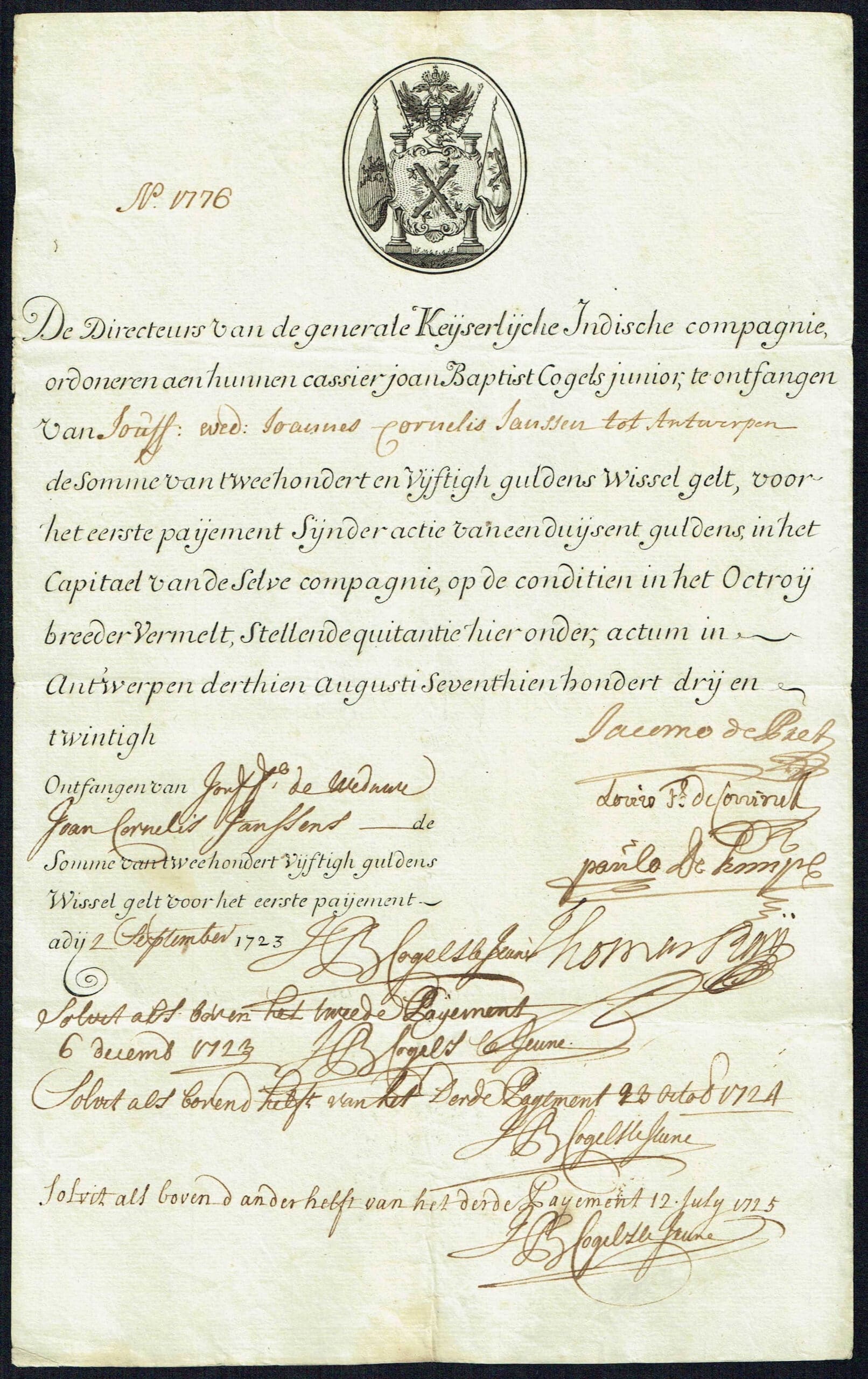

A bond of the General Imperial India Company, better known as the Ostend Company

A bond of the General Imperial India Company, better known as the Ostend Company© Wikimedia Commons

It was not the first time that international trade was conducted on a large scale from Ostend. In 1722 the General Imperial India Company (GIC), better known as the Ostend Company, was already established. This company had received patent from Emperor Charles VI to trade with China and Bengal. The Ostend Company did so extremely successfully, until it was suspended and eventually abolished in 1727 under pressure from neighboring countries. The international activity of the 1780s had little to do with this Company. Firms had to cope without a state monopoly: an extensive network and a favorable political environment were now their most important tools. Many ships sailed to Suriname or traded with Caribbean islands such as Saint Thomas, Martinique, or Grenada. And it wasn’t long before yet another destination appeared on the proverbial radar: Africa.

The driving force behind the trade with Afrika in the South of the Netherlands was Frederik Romberg. He was born in the town of Iserlohn, in what is now Germany. Romberg moved to Brussels in 1755 to start his business. He made fortunes in the transit trade, and company offices with his name on it soon arose in Leuven, Bruges, Ostend, and Ghent. Romberg took full advantage of the war years by selling neutral ship papers to foreign merchants.

Frederik Romberg, the driving force behind the trade between the southern Netherlands and Africa

Frederik Romberg, the driving force behind the trade between the southern Netherlands and Africa© Wikimedia Commons

With the support of the wealthy Brussels colleagues such as Jean-Jacques Chapel and Edouard de Walckiers, the merchant also started equipping ships to the coasts of Africa. The first ship to depart was the Marie Antoinette, named after the French queen and sister of Joseph II. Later ships with names such as the Graaf van Vlaanderen (Count of Flanders), the Staten van Brabant (States of Brabant), or the Vlaamse Zeepaard (Flemish Sea Horse). One of the last ships to sail from Ostend to Central Africa was the King of the Congo

– a name that today sounds like a cynical wink to what would take place a century later.

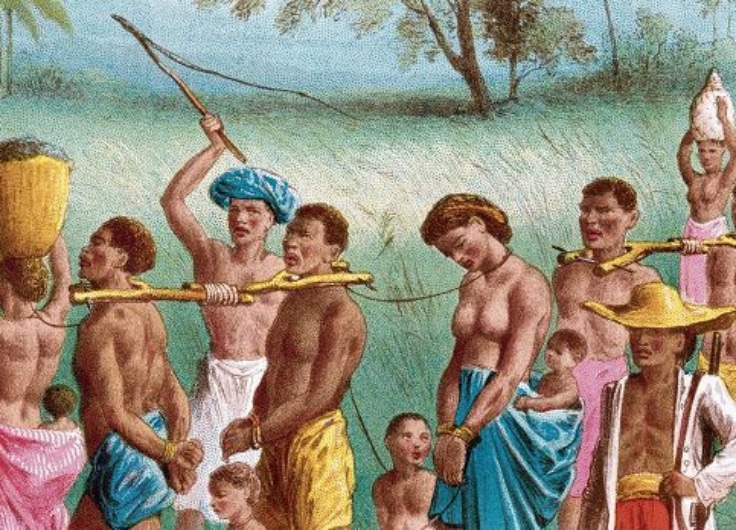

Firearms and cowrie shells

The departure was preceded by a months-long logistics process. In addition to a seaworthy ship, a suitable outbound cargo had to be purchased for exchange in Africa. It was very diverse: in Ghent, Bruges, and Ostend, Romberg employees packed the ships with firearms, spirits, printed cotton, tobacco, ironware and cowry shells, but also mirrors, shoes and handkerchiefs. The recruitment of an experienced captain, a doctor and seamen was another great expense. The crews of Romberg reflected the international character of Ostend: the crew of the Count of Flanders, for example, included Flemings, French, Germans, Italians, and Maltese. Finally, a considerable sum went to food, medicine, insurances and, in the case of the slave trade, chains and shackles.

Thus, it cost a lot of money to set up a company in Africa. It was difficult to convert to modern currency, but the value of the largest equipment was soon of the order of a million euros. How was this money brought together? In the case of early modern international trade, capital owners often pooled together to finance a venture. This was partly due to the size of the amount needed, but also partly to limit the risk. After all, all kinds of things could go wrong on months or even years of international travel.

Map of West Africa (c. 1670), made by John Ogilby, based on Jodocos Hondius and Johannes Janssonius. The area is demarcated based on its economic utility for European traders: Tandtkust, Goudkust, … many trading posts along the coast were also visited by ships from the Southern Netherlands

Map of West Africa (c. 1670), made by John Ogilby, based on Jodocos Hondius and Johannes Janssonius. The area is demarcated based on its economic utility for European traders: Tandtkust, Goudkust, … many trading posts along the coast were also visited by ships from the Southern Netherlands© Wikimedia Commons

In contrary to today, interested parties did not invest directly in Romberg’s company, but they invested in individual trips. Sometimes the trader bundled two or three ships travelling together (fleet) into one share. Romberg and his bankers contributed the majority of capital. But many private individuals also showed interest, convinced by the euphoric atmosphere in Ostend and the high now-or-never mentality of the political circumstances. Portocarero refers in his book to Charles François Vilain XIIII (not to be confused with the well-known statesman Jean-Jacques Philippe Vilain XIIII), but dozens of other wealthy people from present-day Belgium, Amsterdam, Bordeaux, and Vienna signed up for Romberg’s expeditions.

Gold, ivory and human beings

In total, about fifteen ships left for Africa in four years. Initially, they had West Africa as their destination, from present-day Senegal to Ghana. Later, expeditions started their trade at Ouidah, in present-day Benin, or off the coast of Angola. Most of the ships were trafficking in human beings, two or three were solely intended to collect gold and ivory. For example, Romberg instructed the latter captains to buy tusks that ‘are large enough to be processed into billiard balls.’

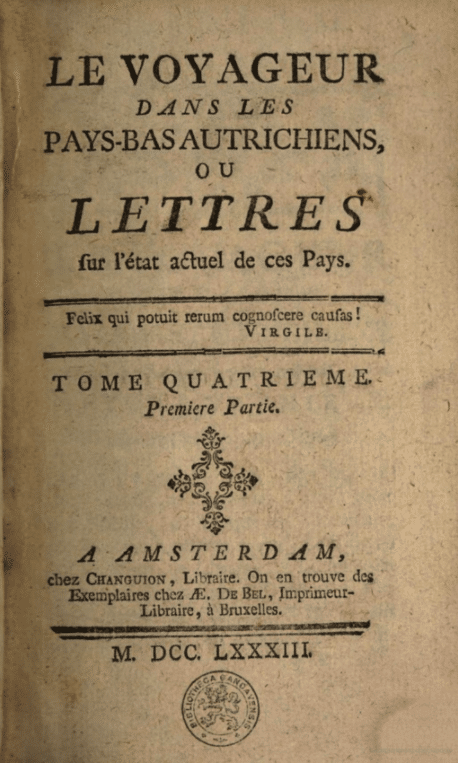

Travel report by Augustin Damiens de Gomicourt

Travel report by Augustin Damiens de Gomicourt© Google Books

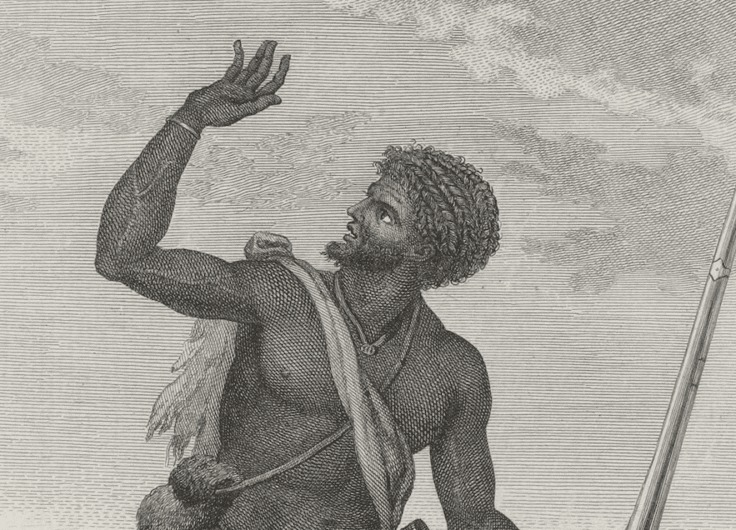

How many enslaved people disappeared in the holds of Romberg’s ships? We don’t know. However, a number that often recurs in the (limited) literature and which is also repeated by Portocarero is five thousand. That estimate can be traced back to Augustin Damiens de Gomicourt, a Frenchman who travelled through our regions between 1782 and 1784 and recorded his observations under the pseudonym Derival. De Gomicourt was a strong believer of commerce for the development of states and never missed an opportunity to praise individuals like Romberg. In doing so, he got carried away and became less critical. For example, the Frenchman firmly writes that Romberg employed ten thousand sailors, only to have to admit a few chapters later that there were only two thousand.

As for the slave trade, De Gomicourt claims that the Marie Antoinette transported two hundred and ninety prisoners, and that the subsequent ships carried another five thousand people. We may also need to adjust this estimate. For example, the Frenchman did not take into account that some ships were exclusively looking for ivory and gold. In addition, privateering and accidents prevented some companies from reaching the shores of Africa. Yet the number of enslaved people that were transported by the Ostend slave ships undoubtedly ran into the thousands.

Scurvy

The organizers and capital providers were aware of the thoroughly violent nature of slave trade. If investors didn’t know it from stories, then certainly because of the prospectus that Romberg had sent them. In the accounting document, however, the violence was disregarded with a business statement of ‘nine to ten percent planned loss’ of the expected number of prisoners. An optimistic estimate: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, an online database with abundant figures on the slave trade, shows that 13 percent of the 6.5 million people abducted from Africa during the eighteenth century alone didn’t make it across the ocean. That already horrific figure is an average, which means that the conditions on many ships were significantly worse.

An example of such a ship was Romberg’s Prince of Saxe-Teschen. The Prince had sailed from Ostend in February 1783 with destination to West Africa. Due to fierce competition from other Europeans, the ship had to stay there for almost a year before enough people were on board to start the Middle Passage, from Africa to America. During the long crossing, scurvy broke out, which left only one hundred and seventeen prisoners alive upon arrival at Cap-Haïtien in Saint-Domingue (Haiti’s former name). The captain, therefore, refrained from travelling to Havana in Cuba, his original final destination, and sailed to Port-au-Prince. To make matters worse, the wind abandoned the Prince on that journey and twenty-six more people died. It is not yet known how many enslaved people were originally on board the ship, but the Prince had at least a capacity of about three hundred and twenty-five prisoners.

The organizers and capital providers were aware of the thoroughly violent nature of slave trade

In addition to the ports of Saint-Domingue, such as the Prince of Saxe-Teschen, the ships from the South of the Netherlands entered other French islands such as Guadeloupe. Havana in Cuba, which was part of the Spanish empire, was also a frequently visited destination. After selling their human cargo, the captains in those places brought on board as much sugar, cotton, coffee, and indigo as their ships could carry and set sail for Europe. Some simply returned to Ostend, others went to Bordeaux in the hope of finding more buyers there for their tropical cargoes.

Unknown history

With the return of peace in Europe, the “Belgian” slave trade from Ostend ended. However, explaining this trade has yet to begin. Despite contributions from historians such as Paul Verhaegen, Hubert van Houtte, Fernand Donnet, Dieudonné Rinchon, and John Everaert, trade with West and Central Africa remains an unknown story. To illustrate: there is currently no single journey from Ostend included in the almost complete Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database.

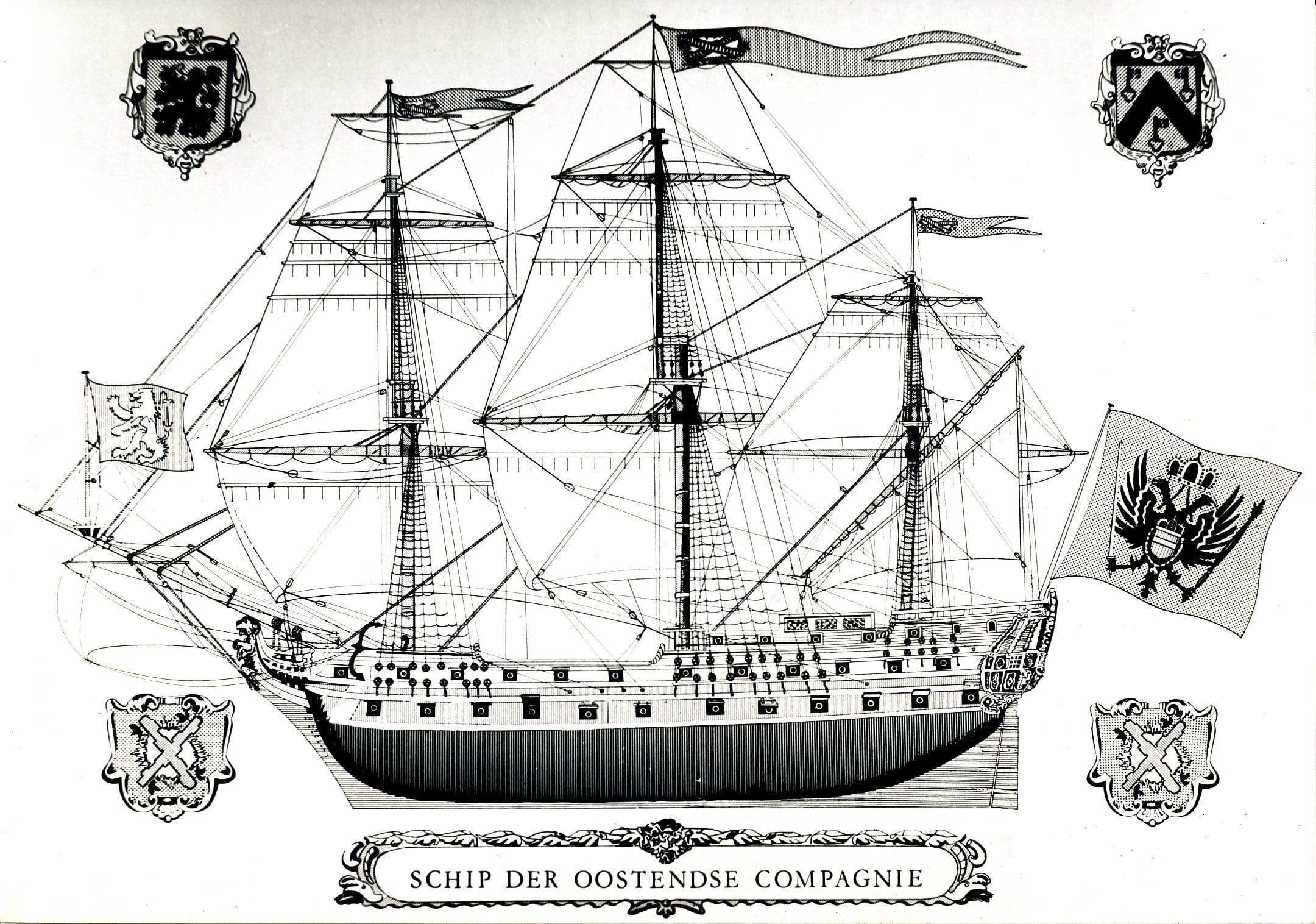

A ship of the Ostend Company

A ship of the Ostend Company© Beeldbank Kusterfgoed

In addition to questions about the scale (the how much question), the how question also remains unanswered: in what way did merchants from the south of the Netherlands such as Romberg manage to integrate into a trans-Atlantic system that was dominated by the great colonial empires? Which domestic and foreign networks did they use? And how did they circumvent or gain access to existing monopolies?

Further research, including my own project in collaboration with KU Leuven, the Flanders Marine Institute, and the Fund for Scientific Research, will address these questions. Placing existing data in a broader perspective and tapping into new source material in Belgium may provide the answer. There is also a lot of important material waiting abroad. Whereas Shaw and De Gomicourt acquired knowledge 250 years ago in the Southern Netherlands and took it with them to England and France, historians will now have to do the opposite. This topic deserves our attention.