The Victory March of the Potato Across Europe Began in the Low Countries

The fact that the potato is familiar to all European cuisines is down to Carolus Clusius, a sixteenth-century botanist from the Southern Netherlands. Clusius was the first to describe the plant, in his magnum opus Rariorum Plantarum Historia. The work also displayed a drawing of the plant, which, along with a 1950s potato harvester, has been included in the Flemish Community’s List of Showpieces. This is how the tuber went from rare medicine to popular staple.

In Spanish chronicles you can read the odd piece here and there about Europeans’ first encounter with the potato. Juan de Castellanos, who arrived in Colombia in 1544, reports on the turmas (truffles) which the indigenous people cultivate there. Pedro de Cieza de León, who travelled to Colombia and Peru between 1536 and 1551, recounts how the natives dry the turma de tierra (earth truffle) in the sun to preserve it. The missionary José de Acosta, who was in the Andes from 1569 to 1585, also noted the sun-drying and claims that the Incas used the potato to make a ‘kind of bread’.

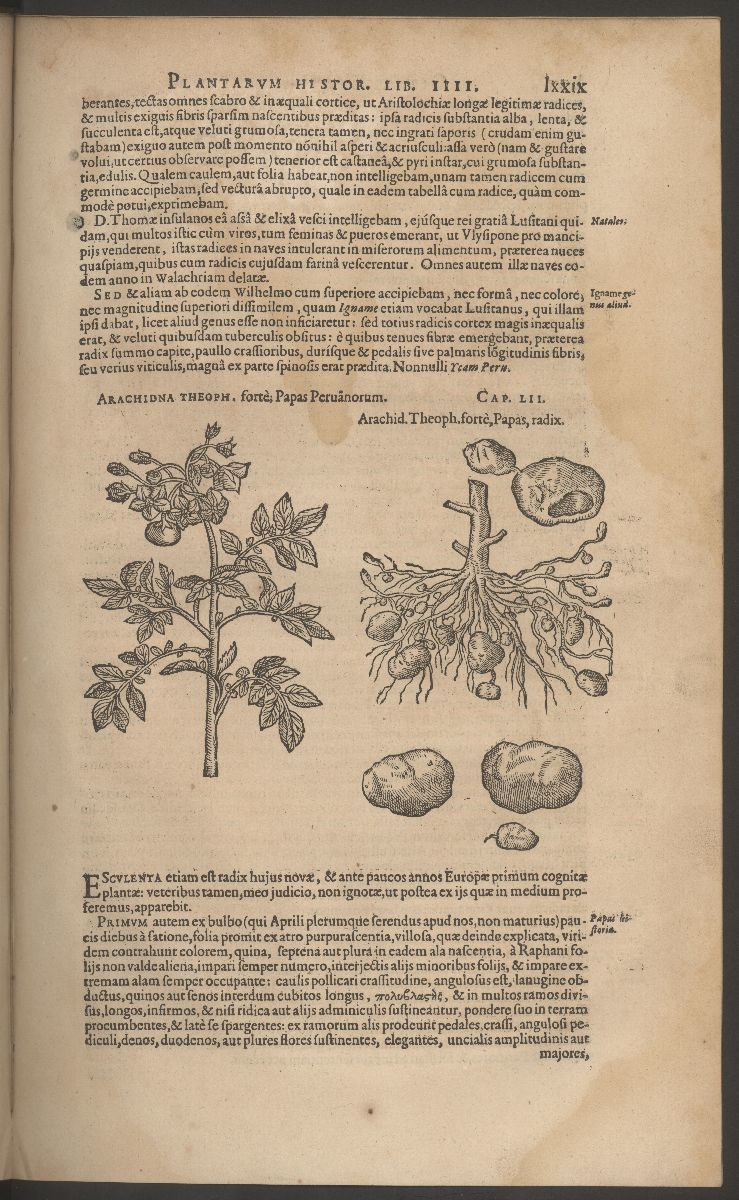

Carolus Clusius, Rariorum platarum historia, Antwerp, Jan I Moretus, 1601

Carolus Clusius, Rariorum platarum historia, Antwerp, Jan I Moretus, 1601© Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, inv. B 954

The Spanish conquistadores introduced the potato and many other plants from the New World into Europe. After the crossing they were transferred to smaller ships on the Canary Islands, then taken to the port of Cadiz and to Seville. The fact that the Canary Islands were the hub for distributing the plant is shown by a document from the archives of Las Palmas which mentions a few dishes of potatoes that were shipped from Gran Canaria to Antwerp on 28 November 1567.

The first potatoes in Europe were to be placed in the ground in Seville, probably in hospital gardens. On the old continent the plant remained more of a medicine than a food until well into the sixteenth century. One story states that the banker Nicola Doria from Genua was doing business in Seville. Saved from drowning he entered the Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel, who used the tubers for medicinal purposes. In 1583 the monk Nicola Doria returned to Italy and presented a few potatoes to the apostolic nuncio Giovanni Francesco Bonomi, who was in weak health. Bonomi always took a few potatoes with him on his journeys, including in October 1586, when he had to chair a provincial council in Mons. The nuncio died in February 1587 and one of his servants handed over the potatoes, under the Italian name taratouffli, to Philippe de Sivry. The governor of Mons was a plant lover. He apparently planted the tubers and from his 1587 harvest he passed on two potatoes to Carolus Clusius in January 1588.

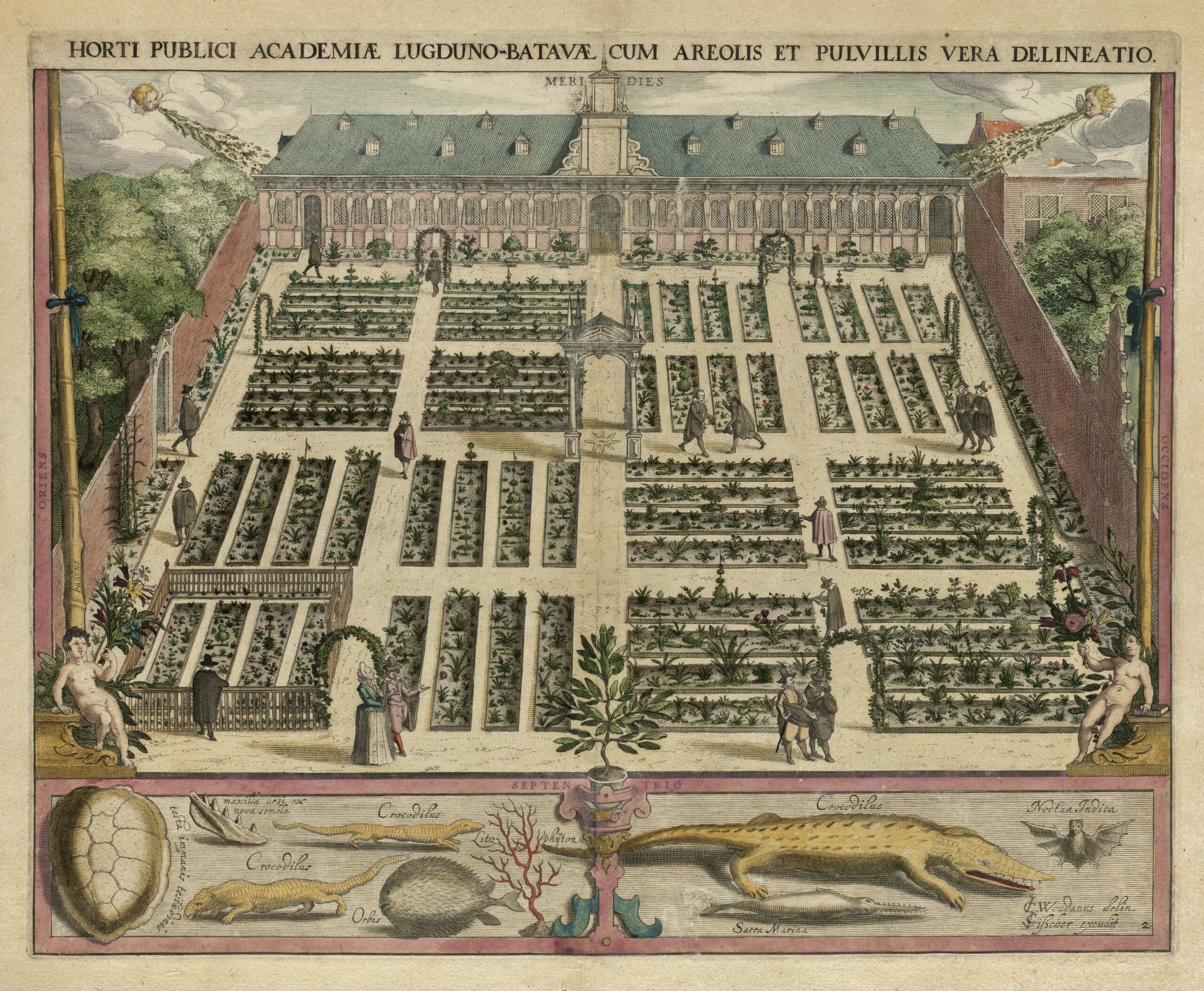

Jan Cornelisz. van ‘t Woudt and Willem Isaacsz. Swanenburg, Gezicht op de Hortus Botanicus van de Universiteit van Leiden (View of the Hortus Botanicus of Leiden University), set up by Carolus Clusius, print published by Claes Jansz. Visscher, Amsterdam 1610

Jan Cornelisz. van ‘t Woudt and Willem Isaacsz. Swanenburg, Gezicht op de Hortus Botanicus van de Universiteit van Leiden (View of the Hortus Botanicus of Leiden University), set up by Carolus Clusius, print published by Claes Jansz. Visscher, Amsterdam 1610A European network

If there is one name that cannot be omitted in connection with the distribution of the potato in Europe, it is that of Carolus Clusius. He was born Charles de l’Écluse in Arras in 1526, the year in which the city and all of Artesia became part of the Habsburg Netherlands. He began his studies in Saint-Vaast and Ghent, studied law and classics in Leuven and medicine in Montpellier, and followed lectures on diverse subjects in a large number of European cities.

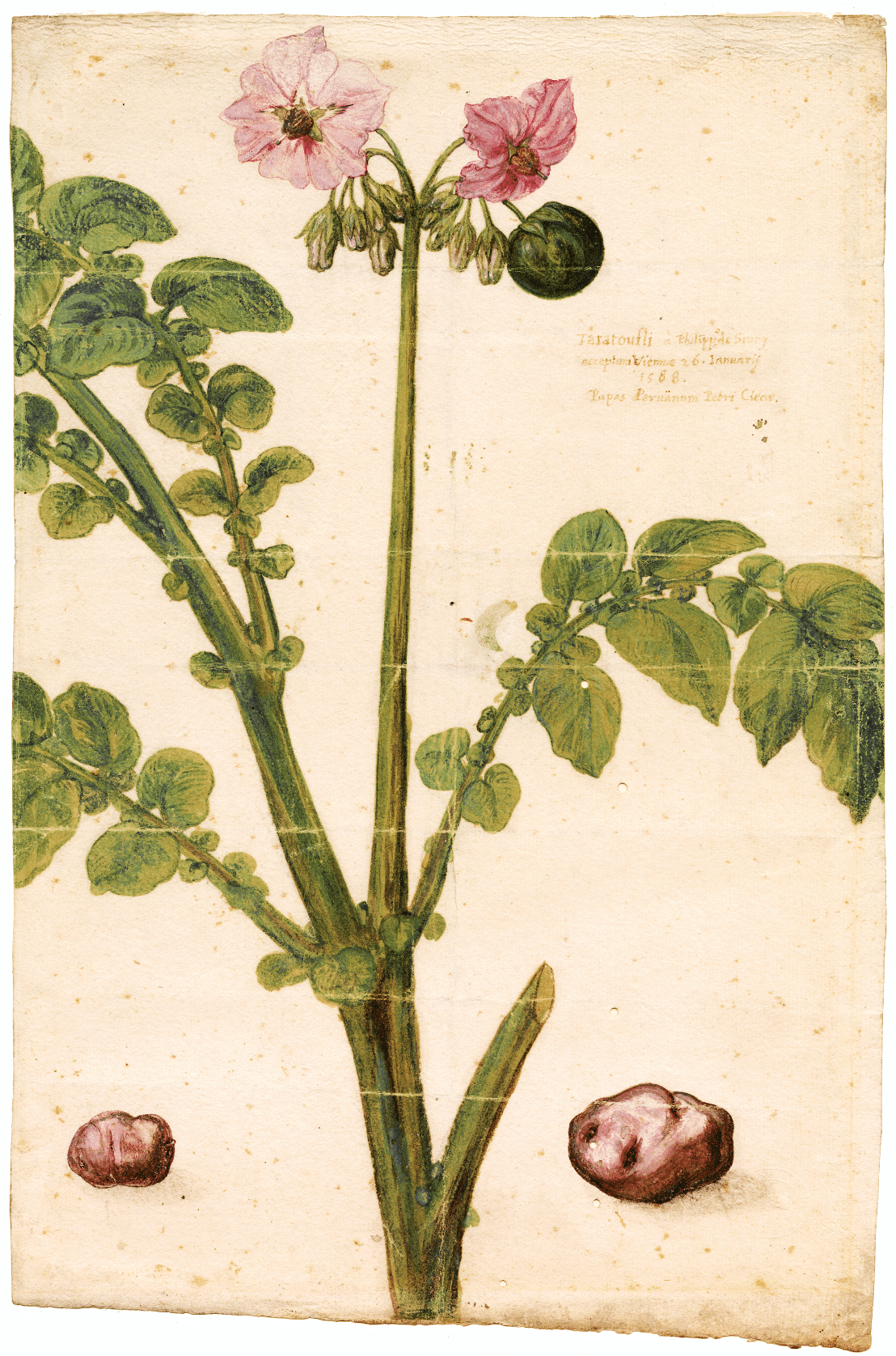

Flemish Community Showpiece: Anonymous, voorstelling van een aardappelplant (presentation of a potato plant), c. 1588

Flemish Community Showpiece: Anonymous, voorstelling van een aardappelplant (presentation of a potato plant), c. 1588© Museum Plantin-Moretus, Antwerp, inv. MPM.TEK 516

In 1557 he translated the Cruydt-boeck of Rembert Dodoens, a botanist from Mechelen, into French. Clusius first came into contact with the living exotic plants in Mechelen, Antwerp and Bruges. In 1560 he visited the wealthy Antwerp apothecary Peeter van Coudenbergh, whose garden was home to a dragon tree from the Canary Islands, as well as pepper plants, tobacco and tomato from the New World, and aubergines, artichokes and pomegranates from the Mediterranean. In 1564 and 1565 Clusius travelled to Spain and Portugal to discover still more plants, flowers and trees.

Carolus Clusius built a network of fellow collectors and botanist colleagues from all over Europe. Two thousand letters to and from this botanist have been preserved, letters which were accompanied by plants, bulbs, tubers and seeds of rare ‘exotic flora’, as Clusius liked to refer to them. He identified all of these plants, named and described them, had them drawn and painted and, above all, cultivated and distributed them.

In broth with lamb and turnips

Between 1573 and 1576 Clusius directed the set-up of the botanic garden of Emperor Maximiliaan II in Vienna. Due to the many diplomatic missions between the Habsburg court and the sultan of Constantinople, in Vienna Clusius came into contact with flowering bulbs from the Middle East, such as narcissi, hyacinths and lilies. From the Flemish nobleman Ogier Ghiselin van Busbecq, ambassador to the emperor in Constantinople, Clusius received a few tulip bulbs. The pair had studied together in Leuven and shared a passion for plants and flowers. The fact that the Netherlands today is a tulip country is thanks to Clusius. In 1593 he arrived in Leiden, where he remained until his death in 1609. The university succeeded in attracting the most famous botanist of the day for the installation of its Hortus. From that ‘Cruydhof’ the tulip began its advance on the whole of the Netherlands.

Portrait of Carolus Clusius in: Jean Jacques Boissard, Icones quinquaginta virorum illustrium doctrina et eruditione praesantium, Officina Bryana, Frankfurt, 1598

Portrait of Carolus Clusius in: Jean Jacques Boissard, Icones quinquaginta virorum illustrium doctrina et eruditione praesantium, Officina Bryana, Frankfurt, 1598Clusius is also important for descriptive botany. In 1576 Christoffel Plantijn published Clusius’ book about the flora of Spain and in 1583 his scholarly description of the flora of Austria and Hungary. He broke with the approach of describing plants for the sake of their useful or harmful properties. Clusius studied the plants for their own sake.

In 1601 Jan I Moretus printed Rariorum plantarum historia, the first part of Clusius’ collected work, including the description and picture of the Papas Peruanorum, the name Clusius had given the potato and which he also wrote on the drawing he had received from Philippe de Sivry in 1589.

That watercolour remains in the collection of the Museum Plantin-Moretus today. In the book we read that he was given two potato tubers and a potato berry by Sivry on 26 January 1588. Clusius informs the reader that the potato tastes pleasant: he ate them regularly, boiled in broth with lamb and turnips. Thanks to his publication and his gigantic network, Clusius’ name remains inextricably linked with the spread of the potato in Europe. Just as important is Clusius’ contribution to the burgeoning of floral still life in Dutch painting. His botanical expertise was a great help to painters such as Joris Hoefnagel.

The first ‘bagger’

The potato long remained limited to a curiosity in the gardens of monasteries, royal palaces and botanists. In the sixteenth century the plant was still low on the scala naturae, because that which grew underground, in the realm of the dead, was deemed unsuitable for human consumption. Moreover, the potato’s berries, which grow on the stems, are particularly poisonous and even the green tubers are best left out of the pot. It was during the many wars of the seventeenth and eighteenth century that hungry mouths devoured the prejudices against the potato. It became a staple because the plant is easy to grow and adapts to any climate, and because potatoes have a long shelf life.

As long as humans and horses provided the muscle for farm work, mechanisation of the potato crop was limited to fairly simple half-automated planting machines and tools which could sow a row at once; the potatoes still had to be dug up by hand. It was not until the breakthrough of the tractor after World War II that heavy machinery appeared in the fields. Frans D’Haeyere’s collection contains a piece from the first generation of large-scale 1950s harvesters, quite a simple construction that can process a large volume with the required precision. Two blades raise the potatoes out of the soil and place them, along with leaves and soil, in large rotating drums. The soil thrown up then falls through the mesh of the drum and back onto the field. The foliage is caught on pins and transported forward, out of the drum. The potatoes go in the opposite direction and land at the back of the drum on a vibrating sieve. They are then lifted by an elevator chain and put into bags. Levers allow the operator to sort them by size. ‘That’s useful, as there has always been plenty of demand for “chip potatoes”,’ says Frans D’Haeyere. He rescued this ‘bagger’, as he calls his machine, from the scrapyard a quarter of a century ago and it is now a Flemish Community Showpiece.

Frans D’Haeyere and his potato harvester Norvan from the 1950s, a Flemish Community Showpiece

Frans D’Haeyere and his potato harvester Norvan from the 1950s, a Flemish Community Showpiece© photo: Saskia Vanderstichele

Flemish businesses had a strong position in the mechanisation of potato growing. This Showpiece, made by Norvan from Sint-Janin-Eremo, testifies to that, as do other potato harvesters in the collection, such as one from SPY (Stevens Poperinge Ieper), which has a broad chain instead of a drum to reduce damage to the potatoes.

Childhood memories in the Spinnekop

The Spinnekop, a Flemish Community Showpiece, is still regularly taken out of the barn.

The Spinnekop, a Flemish Community Showpiece, is still regularly taken out of the barn.© photo: Saskia Vanderstichele

In what was once the large calving barn in Geel, Frans D’Haeyere has a second Showpiece: a bright-green Spinnekop in its original state. It is one of the few preserved specimens of this small tractor brought onto the market by Georges Favache of Vilvoorde immediately after World War II. Frans sometimes gets the Spinnekop and other machines out of the barn for demonstrations. When he has the chance to work the field with them, it takes him pleasantly back to his childhood.

The collection contains many more special tractors. The imposing 1939 German Lanz Bulldog was an inspiration to several other constructors. In order to set the British Field-Marshall in motion a ‘cartouche’ has to be pushed into the side of the engine, then a wad of burning paper placed in a little hole at the front; you then hit the cartouche with a hammer, and the engine starts. The Italian Landini has a hot bulb at the front which must be heated with a flame in order to start the engine.

Part of the collection of Frans D'Haeyere

Part of the collection of Frans D'Haeyere© photo: Saskia Vanderstichele

There are several collectors of tractors and Frans D’Haeyere’s collection also began with one, but there are few people like him who also bring together other agricultural machinery. Where does his passion come from? Frans was born in 1940 in Meulebeke in West Flanders, where his parents had a small farm. Every summer the young Frans looked forward to the arrival of the combine harvester which came to harvest the farmers’ grain. To him that was the highlight of the year. In 1954 the family moved to a larger farm in Wallonia and were among the first there to grow potatoes, because ‘les patates’ were just something ‘pour les flamands’, Frans remembers the Walloon farmers remarking. The combine harvesters he had seen in Flanders and the potato harvesters in Wallonia sowed the seeds for the collection, which focuses on the grain and potato harvest.

Frans D’Haeyere with his personal ‘showpiece’: the Claeys thresher from just after World War II

Frans D’Haeyere with his personal ‘showpiece’: the Claeys thresher from just after World War II© photo: Saskia Vanderstichele

Among all the machines he collected, Frans proudly reveals his personal ‘showpiece’: a gigantic ‘Claeys thresher’ from just after the war which, as you can read from the side, was in service to the contract worker Desmadryl in West Flanders. There is also a 1937 Excelsior hay press from Zedelgem, Frans points out, as well as a Massey Harris combine harvester which crossed the ocean under the Marshall Plan, just like the first potatoes four hundred years earlier …

This article previously appeared in OKV.