The Vital Role of Translation in the Black Lives Matter Era

Translation throws up numerous issues, many of which go beyond linguistic dilemmas. As Dutch Studies students at the University of Sheffield, this wasn’t a new discovery – we know language and culture are inseparable – but one issue came to dominate our recent translation project, one which took introspection and discussion. Is it appropriate for us, as white students, to translate texts about Black experiences of slavery, something far removed from our lived reality?

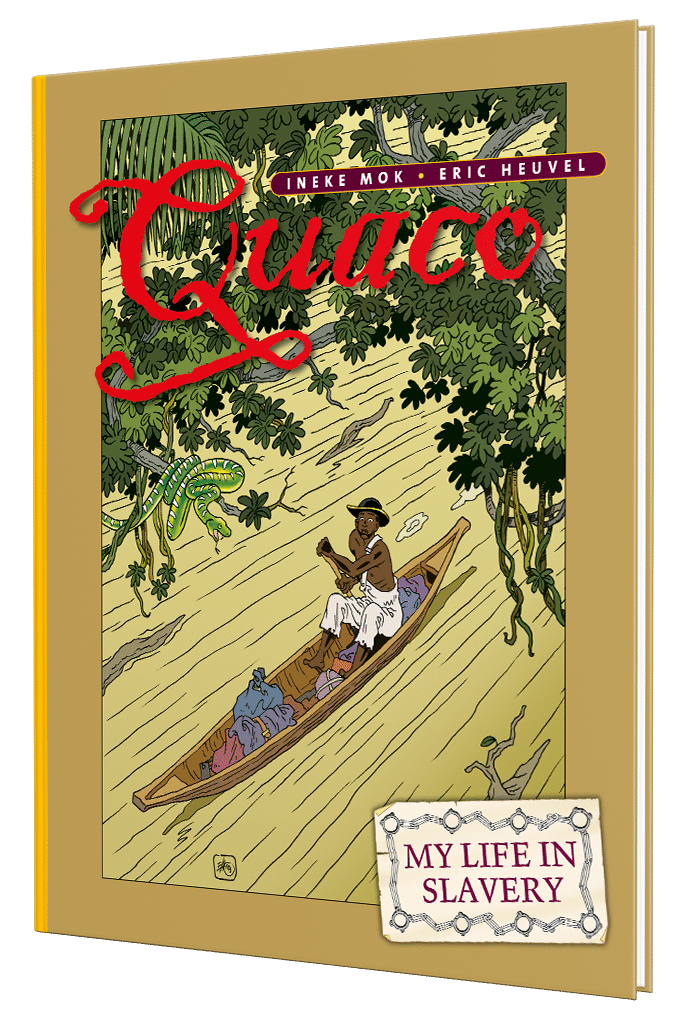

Our project, on the surface, seemed simple: to translate the Dutch graphic novel Quaco. Life in Slavery, written by Ineke Mok and illustrated by Eric Heuvel. Designed to teach younger audiences about the atrocities of the Atlantic slave trade, the plot recounts the real-life personal experience of a boy named Quaco who was abducted from his home in West Africa by the Dutch, taken to their colony of Suriname and enslaved as a futuboi – a personal servant boy – to John Gabriel Stedman, a Scottish-Dutch military officer.

Cover of the English edition of the graphic novel 'Quaco'

Cover of the English edition of the graphic novel 'Quaco'The story of Quaco’s life, which is told from his perspective, opens our eyes to the brutality faced by the over twelve million enslaved people who were forcibly transported to the Americas, including but not limited to abduction, lashings, skin brandings, forced labour, starvation and a dehumanising lack of freedom.

In the second stage of this project, a group of eleven University of Sheffield students (including myself) translated the educational materials that accompany the already-translated graphic novel, a task which obviously called for a sensitive translation. The text had to remain accessible and engaging to current school students, but at the same time we had to ensure that the cruelty experienced by enslaved people wasn’t sugar-coated or evaded, since those aspects are key to exposing the realities of slavery.

Context is vital: a white character from the 18th century using offensive terms in the graphic novel shows the horrors Quaco faced in his everyday life. A secondary school teacher using such words in their lessons and worksheets in 2022 would simply be offensive. So, these learning resources required a different approach to translation, one which considered our intended audience of TikToking 21st-century teens. While discussing these issues during our preparations, before even translating a single word, we stumbled upon an important question: as eleven white European students, are we qualified to translate this story recounting a Black experience?

Everything about our lives seems far removed from Quaco’s. Our ethnicity, education, country of origin, where we live now – all factors that could influence our choices during the translation. Yet none of them are even close to Quaco’s lived experiences. How could we, with our comparatively privileged lives, be suitable translators for this project?

How could we, with our comparatively privileged lives, be suitable translators for this project?

We weren’t the only ones asking ourselves this question. A wider discussion developed in the wake of African-American poet Amanda Gorman’s recital of her poem ‘The Hill We Climb’ at the inauguration of Joe Biden, when Marieke Lucas Rijneveld was selected to translate the text into Dutch. Her lack of experience in the field of translation, as well as her appointment over Dutch spoken word poets of colour, caused an uproar that led Rijneveld to pull out of the translation altogether. Should we have been considering the same course of action?

Dutch journalist and diversity activist Janice Deul

Dutch journalist and diversity activist Janice Deul© Twitter account Janice Deul

To come to a conclusion on that question, we have to consider what caused the uproar in the first place. To those who were disappointed by Rijneveld’s appointment, like Dutch journalist and diversity activist Janice Deul, the poem was a milestone in the Black Lives Matter movement thanks to its timing, writer and subject matter. So giving this particular poem with all its contemporary significance to a white author felt out of place, since it ignored the cultural baggage and activistic value intrinsic to the poem. As Deul stressed, the poem’s distinctive context is key: “I’m not saying a black person can’t translate white work, and vice versa”.

Now, we had a judgement call to make, one which required us to consider the text itself. For us, the text’s main purpose was clear: it should educate young people about history. Not just the history that many of us learnt at school, where we were taught to take pride in events from a canon of nationally significant moments. But a real, critical version of European colonialism, where we no longer ignore the Black voices and experiences that have been marginalised and omitted over centuries. Quaco’s voice is one of many that needs to be amplified, so that as many people as possible in as many countries as possible can hear his story.

While I do believe this translation project would have benefitted from more Black voices, I also believe that we as white people also have to do our part in amplifying Black experiences to the world

After all, one of the lessons of the Black Lives Matter movement is that we all need to inspire change – real change – for the future. To truly decolonise our curriculums, teachers need to have as many resources as possible that allow them to show their students Black history and the atrocities of our slave-trading past. While I do believe this project would have benefitted from more Black voices, I also believe that we as white people also have to do our part in amplifying Black experiences to the world. As Gorman says in her inaugural poem, “we know our inaction and inertia will be the inheritance of the next generation, become the future”. For our project, aimed at this next generation, this could hardly be truer.

Our translation efforts aren’t a milestone like Gorman’s poem. Rather, they are a response to her rallying cry. By helping to gain historical justice for Quaco, spreading his story to English speakers and raising awareness of the historical oppression of Black people perpetrated by both the Dutch and the British, we want to contribute to this worldwide effort to elevate Black voices. Hopefully, we are but one of many projects which help to quietly cause a revolution in classrooms across the UK – a revolution which we believe is long overdue.