The War Left Its Mark on Raoul Servais, and Raoul Servais Left His Mark on the War

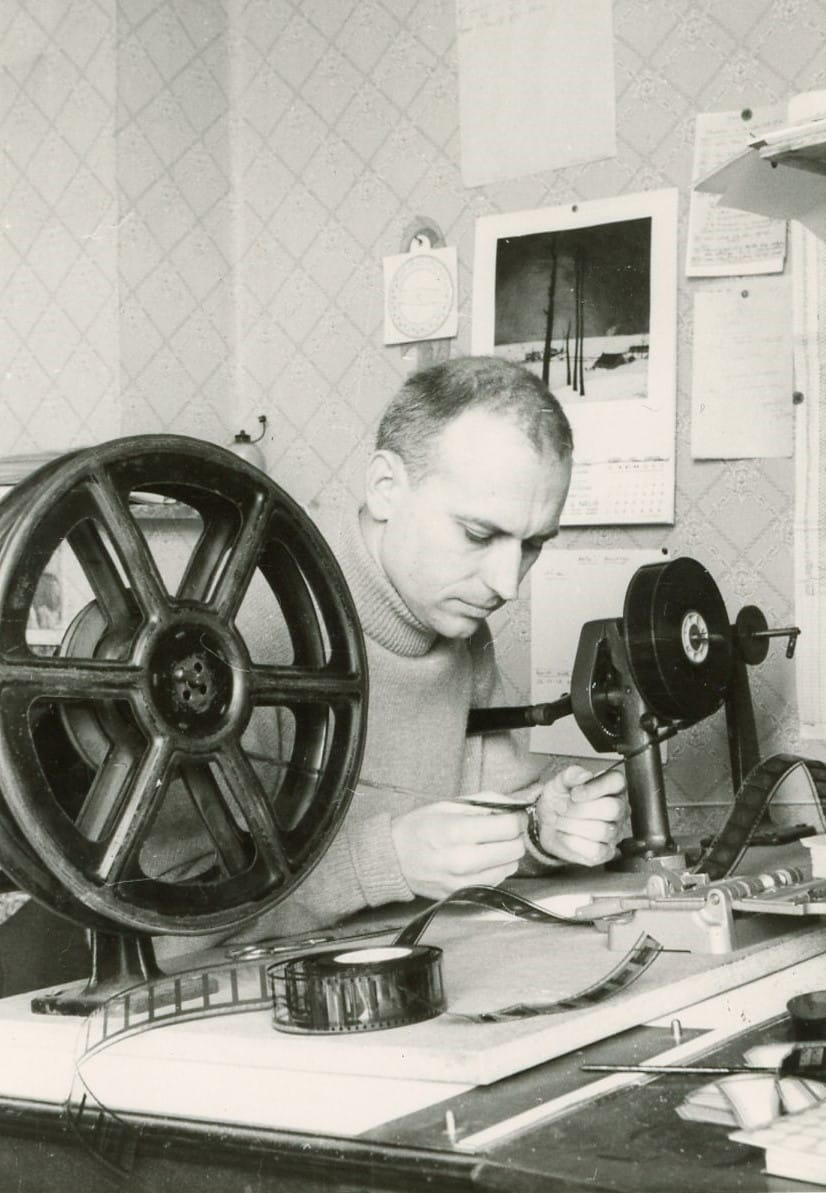

Raoul Servais escaped death more than once during the Second World War. The award-winning Ostend filmmaker and animator (1928-2023) would later put that war legacy to creative use. A new exhibition at the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres and a publication closely examine Servais’ war memories.

‘Through the opening of the bunker, about ten metres in front of me, I suddenly saw a flash of light, followed by a huge cloud of dust and debris. No sound of an explosion, except for the continuous sharp whistle hurting my eardrums. I saw a boy through the smoke. His back was ripped open by shrapnel. He staggered, fell, crawled back up and managed to walk into the barn. The ground along his path was covered with shreds of chickens and rabbits, some of them stuck to barn walls.’

Raoul Servais

Raoul Servais© Raoul Servais / Raoul Servais Collection

‘I don’t remember anything about the impact. No doubt the shell had blown apart the rabbit and chicken coops when it exploded. Was that the reason why not a single shard had hit our bunker? More so, and given my position, you can be sure that it would not have spared me.’

That’s how Raoul Servais (Ostend, 1928-2023) recalled one of the treacherous situations he had experienced at the beginning of the Second World War. The experiences and impressions of 1940-1945 would go on to haunt him. The war is perpetuated in his short films, in the hundreds of drawings and watercolours he has produced in the last years, and in his recently published war memoirs.

Marked by war

On 10 May 1940, Nazi Germany invaded the Low Countries. Barely three days later, the Luftwaffe dropped its first series of bombs on the coastal town of Ostend. Raoul was slightly injured. Meanwhile, thousands of refugees flocked to Ostend hoping to catch a boat to England. The German Blitzkrieg was unstoppable.

The upbringing

The upbringing© Raoul Servais / Raoul Servais Collection

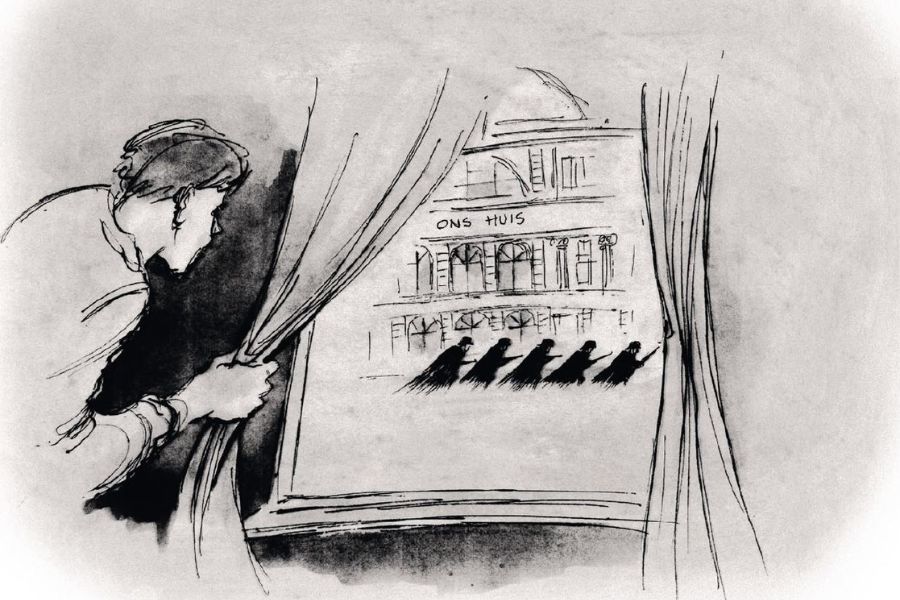

These circumstances forced Raoul, his brother André and his mother Adrienne Boussy to flee to France. They were not alone. In the days of May 1940, about two million Belgians fled, even more than at the height of the exodus in 1914, when one and a half million people fled Belgium. The vast majority would not get far. Due to the rapid advance of the Germans to Abbeville, no one would get past the Somme. Refugees were unsuccessful and forced to return.

This was also the case for Raoul Servais. During his journey back, the brutality of war suddenly came very close. In Wulpen, a village near the Belgian coast, Adrienne and her two sons were forced to take shelter with a dozen others in a bunker located near a farmstead. Raoul experienced four terrible days and nights there.

© Raoul Servais / Raoul Servais Collection

Outside, the German and French troops were engaged in combat. At one point, bullets were fired through the bunker’s observation hole. They brushed Raoul’s crown, bounced off the wall and landed in a man’s thigh and a child’s arm, thankfully, without much harm. A few moments later, from inside the bunker, he watched as the farmhand was hit by shrapnel, the fragment quoted above.

By the end of May 1940, the Servais family had returned to Ostend. During their absence, the city had been badly struck by aerial bombardment. They found their house on Kapellestraat in ruins. Difficult years ensued. The young Raoul became acquainted with restricted freedom, troublesome food distribution, propaganda, collaboration and the New Order, resistance and deportation, the arrest of Jews and – later – the return of people from the camps.

Souvenirs de guerre

Those who experience a war will be forever marked. When the ‘thread of memory’ started wearing thinner, Raoul Servais decided to also entrust everything he remembered to paper.

Still from ‘Chromophobia’ (1965)

Still from ‘Chromophobia’ (1965)© Raoul Servais / Raoul Servais Collection

He penned the first part, which dealt with the outbreak of the Second World War and the fleeing experience, in 1995. The second part, expanding on the events he experienced during the occupation and liberation, was written between 2008 and 2012. Raoul also added fifteen illustrations to the manuscript.

Notably, the text includes numerous references to and anecdotes about the First World War. One example is the story Mummy about his beloved mother Adrienne Boussy who, with her parents and brother, fled the violence of war to England in October 1914. They did not return to Ostend until 1919. Adrienne was left with a lifelong passion for the English language, which she was later keen on sharing with her children, as well as stories of exile in England. Striking detail: Raoul and his mother were both twelve years old when they had to flee war (for the first time), in 1940 and 1914 respectively.

Raoul Servais became acquainted with the war of 1914-1918 at a young age, also through other family members. His grandfather, Emile Servais, had a large collection of books about the Great War, which he was allowed to browse through freely. Additionally, his uncle, Albert Servais, had fought in the war as a Belgian soldier; the onslaught of the first months of war, the trenches along the Yser Front, the major final offensive that led to the Armistice of 11 November 1918 – he had experienced it all.

© Collection In Flanders Fields Museum

Stories about 1914-1918 were told regularly, and like Emile, Uncle Albert also owned a collection of books about the First World War. It was there that Raoul discovered Vive la Guerre! Hoch Krieg!, a collection of pacifist drawings by Robert Fuzier published in 1932. According to Raoul, discovering the work of Fuzier – a French veteran turned press cartoonist – shaped his bewilderment at the phenomenon of war.

Those who look closely at Fuzier’s drawings will also see the Frenchman’s influence on the work of Servais. Fuzier’s mockery of militarism distantly resonates with the tricks the ginger harlequin Till Eulenspiegel uses to fool the legions in Chromophobia.

War as an endless source of inspiration

In an interview in 2008, Servais said that, for him, there was a life before and after war. This applies to everyone who has intensely experienced the devastation of war. Servais’ immensely creative spirit has put that legacy to use. The memories of the Second and First World Wars, from his own experience and recounted to him, became an endless source of inspiration for his work.

Illustration from 'Memories of War' (2023)

Illustration from 'Memories of War' (2023)© Raoul Servais / Raoul Servais Collection

Moreover, Servais spent his entire life reading up on both wars in order to place his insights about the phenomenon of war into the correct historical context. This determination resulted in, among other things, masterly animation films. In the timeless and unsurpassed Chromophobia

(1965), Servais mischievously and light-heartedly denounces the mechanisms and excesses of authoritarian regimes. And in Operation X-70 (1971), the threat of weapons of mass destruction occupies a central role.

Inspired by the 2014-2018 centenary commemoration, in more recent work, Servais returned to the First World War with the (short) films Tank

(2015) and Der Lange Kerl (2022). The latter can also be regarded as a prelude to the Duiven series, which is currently being developed. For this too, Servais was inspired by the horrors and futility of the First World War. Pigeons are a common thread in the stories, but the numerous nationalities – including Senegalese – that took part in the war in Belgium are also addressed.

The four short films mentioned are at the core of the temporary exhibition held at the In Flanders Fields Museum. It focuses on the theme of war in Servais’ life and work. Additionally, the expo includes a selection from the hundreds of drawings and watercolours which Servais produced in recent years. Noteworthy: his most recent work deals almost exclusively with the theme of war. Servais incorporates images etched in his memory from 1940-1945 with interpretations from his years of study. The emphasis is always on the rejection of repression and violence, both against individuals and groups of people.

© Raoul Servais / Raoul Servais Collection

Raoul Servais’ war memoirs were a major source of inspiration in creating the exhibition. At first, these souvenirs de guerre (originally written in French) were only meant for his immediate family. The King Baudouin Foundation, which plays an important role in preserving Servais’ work and bringing it to the public, seized the opportunity presented by the expo to bring out an illustrated publication.

In Oorlogsherinneringen (Memories of War) historical facts, memories, reflections, imagination and humour are intimately intertwined. Servais knows how to tell a story. This publication adds a new dimension to Servais’ oeuvre and all that has been written about him. It’s essential reading for a better understanding of his work and character, but also a text that stands alone and confidently merges with the chorus of voices against war.

The expo Raoul Servais – Memories of War will be held until 31 May 2023 at the In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres. An accompanying publication is also available in English.