The World’s First Yiddish Newspaper Was Printed in Amsterdam

Uri Faybesh Halevi was his name and he was the publisher of the very first Yiddish newspaper in the world. A serious news publication, not a tabloid. Amsterdam librarian David Montezinos happened upon the Kurant more than two centuries later. What did the paper write about and who were its readers?

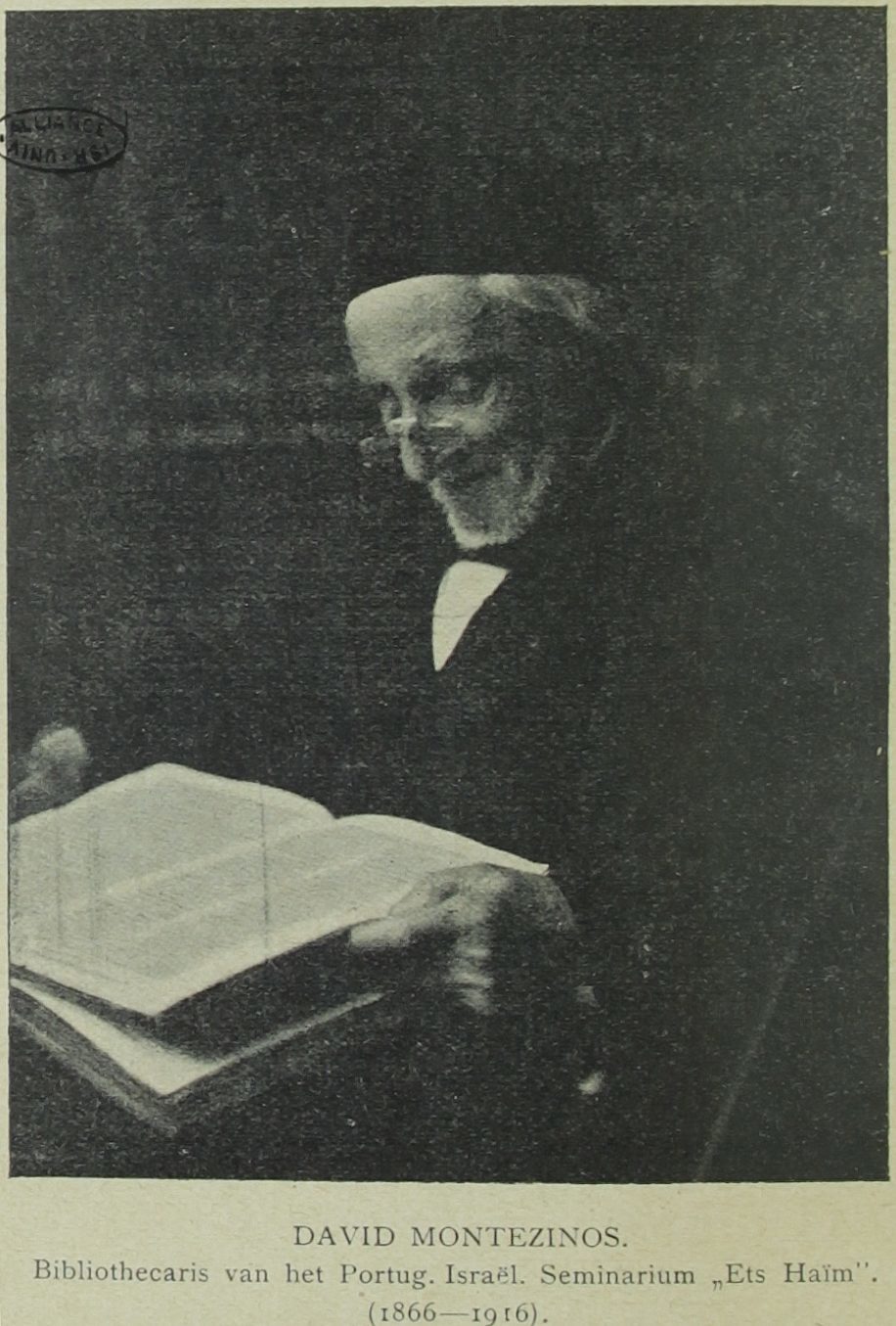

David Montezinos, librarian of Ets Haim, the library of the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam

David Montezinos, librarian of Ets Haim, the library of the Portuguese synagogue in AmsterdamDavid Montezinos (1828-1916), book collector and librarian of Ets Haim, the library of the Portuguese synagogue in Amsterdam, was always searching for rare books. On 29 August 1902, he was standing on Nieuwe Amstelstraat watching the fire at the Flora Theatre, when he was approached by a travelling book salesman. The man showed him a collection of a hundred issues of an unknown Yiddish newspaper, printed in Amsterdam and dating back to the 17th century, the Kurant. Montezinos bought the collection without hesitation.

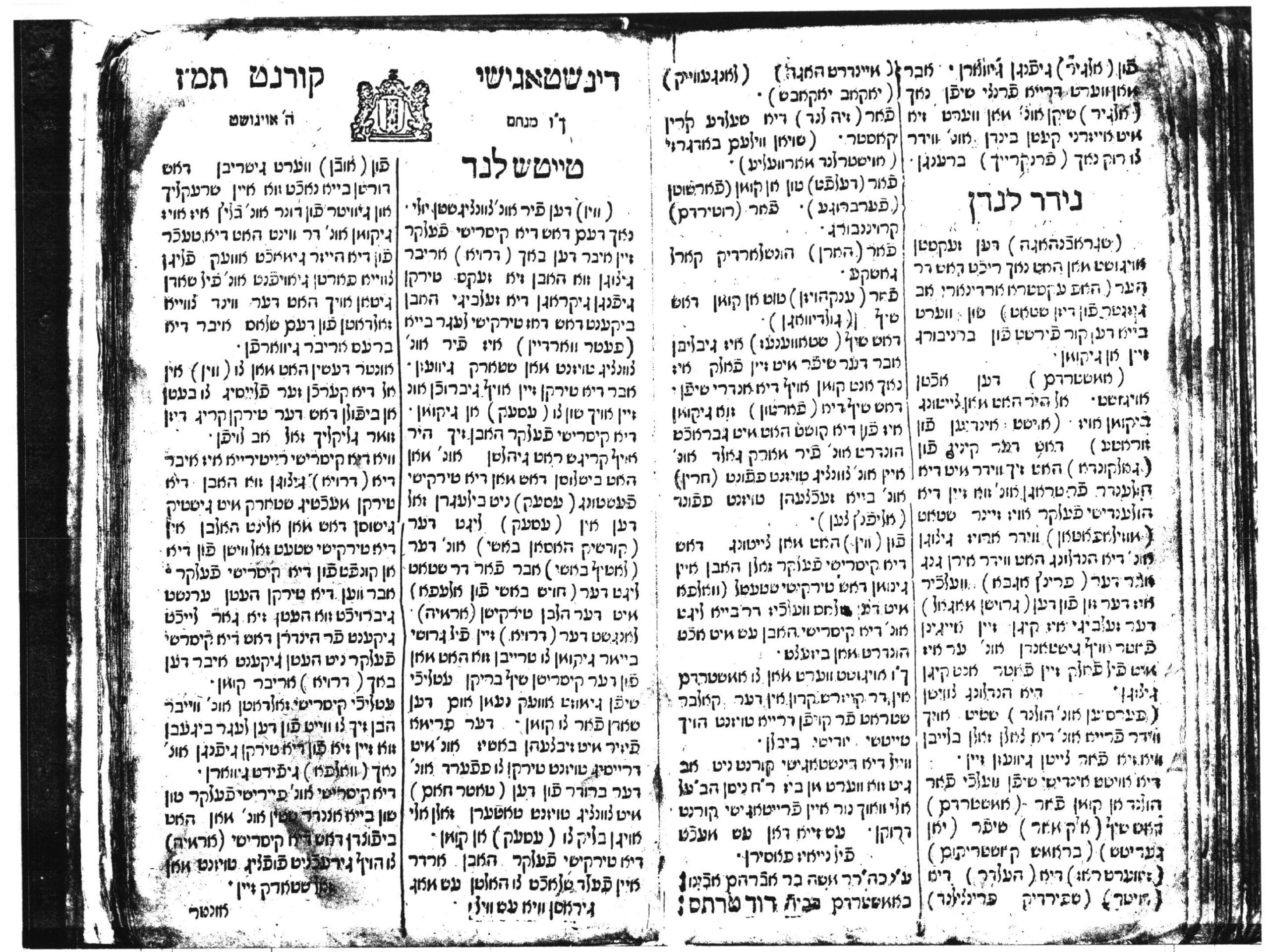

What he had in his hands was the oldest Yiddish newspaper in the world. It was clear that this was not just any old tabloid: the Kurant was a serious newspaper, focusing mainly on international affairs. The copies in the collection were published by two printers: editions from 9 August 1686 to 3 June 1687 were produced by the Ashkenazi printer Uri Faybesh Halevi, also known as ‘Philips Levi van de Velde’; those from 6 June to 5 December 1687 by the Sephardi printer David de Castro Tartas. Both made use of the same typesetter and editor, Moshe Bar Avraham Avinu, or as his name was probably pronounced at the time, Moushe Bar Avrom Ovinu. The newspaper appeared on Tuesdays and Fridays, although in two periods it only came out on Fridays because the Tuesday edition did not sell so well.

Tuesday edition of the Kurant, 1687

Tuesday edition of the Kurant, 1687© Special Collections Amsterdam University Library

Odd one out

Who read the Kurant? After the Spanish-speaking Sephardi Jews had settled in Amsterdam in the 16th

century, in the 17th century it was mainly Ashkenazi Jews who came to the city, from Central and Eastern Europe. They spoke Yiddish and were generally poor and less educated than the Sephardim. The outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618 had set in motion a stream of refugees from Germany, later followed by Jews from Poland and Lithuania fleeing from pogroms and other wars. Not everyone came to Amsterdam to avoid war; the city was known as a place where Jews could live relatively well. At the end of the 17th

century 8000 Jews lived in the Republic, of whom 6000 – half of them Ashkenazim – lived in Amsterdam.

The Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, painting by Emanuel de Witte, 1680

The Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, painting by Emanuel de Witte, 1680© Rijksmuseum

Amsterdam was the centre of Hebrew and Yiddish book production for both domestic and international markets. Among the largely religious works, the Kurant was the odd one out. There was a need for a Yiddish newspaper. Many Ashkenazi Jews lived in profound poverty, but some businesspeople wanted to keep abreast of the situation in the world to talk about it with their non-Jewish business relations. Such a newspaper had to be in Yiddish because they had not (yet) sufficiently mastered Dutch.

Background

The first printer and publisher of the Kurant was the Ashkenazi Uri Faybesh (Phoebus) Halevi (1627-1715), who was born in Amsterdam. His grandfather and father had come from Emden to Amsterdam at a time before many Ashkenazi Jews lived there. They moved in Sephardi circles, working as kosher butchers among other things. The story goes that they retaught Jewish customs to Sephardi immigrants who had been forced to convert to Catholicism. Uri Faybesh Halevi thus soon came to be familiar with the Sephardi community. And due to his marriage to his niece, whose father (married to Uri’s older sister) was of Christian background, he also had contact outside the Jewish world.

The schools and sanitation facilities at the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, c. 1695, etching by Romeyn de Hooghe, c. 1695

The schools and sanitation facilities at the Portuguese Synagogue in Amsterdam, c. 1695, etching by Romeyn de Hooghe, c. 1695© Rijksmuseum

In 1658 Halevi started up his own printing press and publishing company and became a leading Jewish printer. His most ambitious project was the publication of a Yiddish translation of the Hebrew Bible, which brought him to the edge of a financial abyss. In 1686 he had to mortgage part of his stock. This was also the year in which the first known edition of the Kurant came out. Perhaps he was also inspired by Sephardi and Christian printers, with whom he associated a great deal. In fact, in the publishing world, there was a great deal of contact between Ashkenazim and Sephardim and between Jews and Christians. The guild of book printers, sellers and binders was one of the few guilds to admit Jews.

Example

Halevi wrote in the preface to the Yiddish Bible translation that the Sephardim had inspired him to publish in the vernacular. He also felt that his Bible translation, inspired by the 1637 Dutch Statenvertaling (the first Dutch Bible translation), provided Jews with the knowledge to discuss religious subjects with Christians. It is quite conceivable that he intended the Kurant to allow Jews to enter the discussion about world affairs.

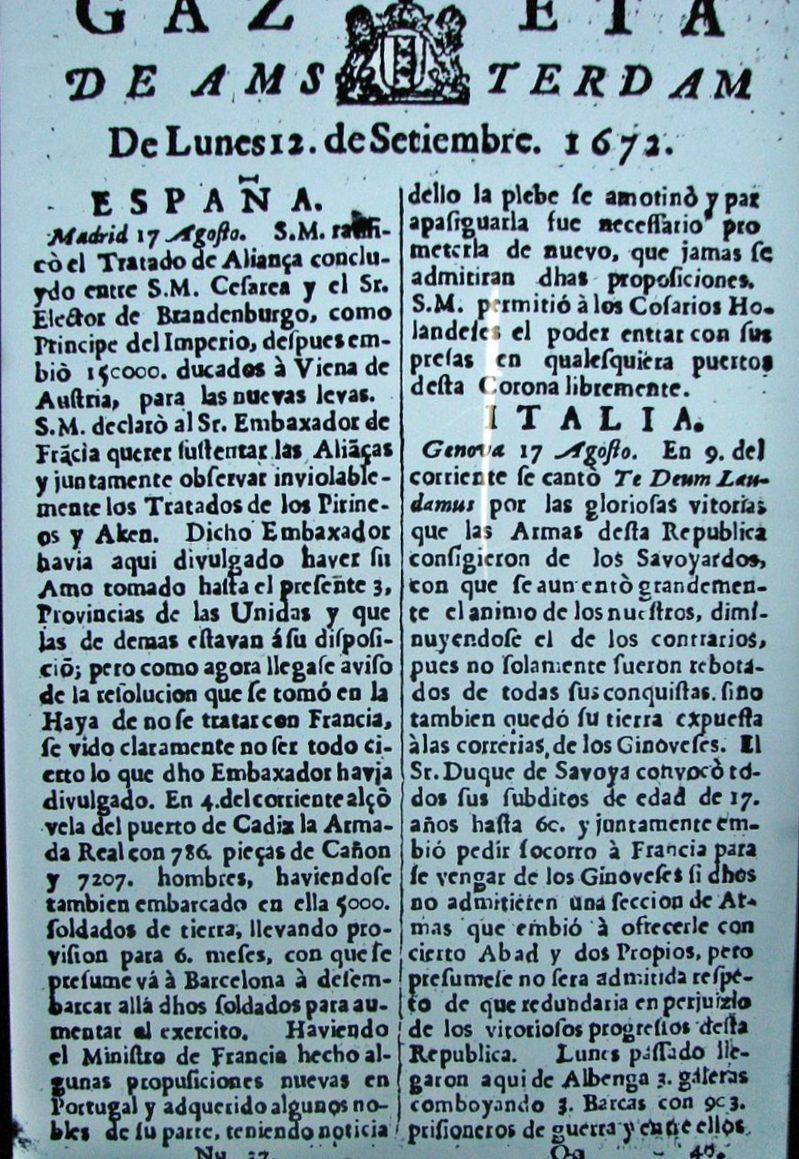

Front page of the Spanish Jewish newspaper, published in 1672. The newspaper of the exiled Jewish community in Amsterdam was printed by David de Castro Tartas

Front page of the Spanish Jewish newspaper, published in 1672. The newspaper of the exiled Jewish community in Amsterdam was printed by David de Castro Tartas© Wikipedia

In June 1687 for unknown reasons he transferred the Kurant to the Sephardi David de Castro Tartas. Born in the southern French town of Tartas, he had come to the Netherlands in 1640. In 1662 he started up a printing and publishing company, producing prayer books in Hebrew and Spanish, as well as Yiddish novels and history books. He also published newspapers, the most famous of which was the Spanish Gazeta de Amsterdam, which existed for a good thirty years, from 1672 to 1702, and was probably intended both for Jews of Sephardi origin and non-Jews. The Gazeta may have provided an example for Halevi.

Intermediary

The Kurant relied on typesetter and editor Moushe bar Avrom Ovinu (who died in 1733/1734), also known as Moses Abrahamsz or Moses Polak. He had been born a Christian in Nikolsburg, today the Czech town of Mikulov, at the time the main centre for the Moravian Jews. Moushe converted to Judaism and came to Amsterdam at the start of the 1680s after he had married a Jewish wife. In 1686 he translated a Hebrew book into Yiddish for Halevi. Given that he was a German speaker and knew the Latin alphabet, he probably did not have too much difficulty with Dutch newspaper reports and it was likely for him to offer his services as a translator and editor. Typesetters often functioned as intermediaries between the Jewish and the Christian world.

The content of the Kurant was around 80% derived from other papers

The Kurant barely produced its own news. The Jewish printers were almost always short of money and could not afford paid correspondents or press offices, as some Dutch newspapers could. Moushe, therefore, reached for the most important two newspapers, which at the time appeared three times per week: the Oprechte Haerlemse Courant and the Amsterdamse Courant. The content of the Kurant is around 80% derived from these two papers. Moushe skilfully ‘cut and pasted’ to create running stories from their reports, providing supplementary explanations of potentially unfamiliar issues and simplifying the language to meet the needs of his readers.

The newspapers were full of war news, especially on the war between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, the highlight being the defeat of the Turks in the Hungarian city of Buda in September 1686. Although the Republic did not take part in that war, in public opinion there was a great deal of fear of ‘the Turks’, who had large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe in their power.

The siege of Buda, a painting by the Flemish Frans Geffels (1686); this and other conflicts dominated the columns of the Kurant. Many readers came from the warzones.

The siege of Buda, a painting by the Flemish Frans Geffels (1686); this and other conflicts dominated the columns of the Kurant. Many readers came from the warzones.© Hungarian National Museum, Budapest

Human interest

The war in Hungary featured in the Kurant far more than it did in the Dutch newspapers as the most important topic and filled more than half the columns. Other armed conflicts in Europe were also present. Many readers of the Kurant or their parents had fled war in Eastern Europe or had family there. Furthermore, Ashkenazi businessmen in the Republic, specifically the Gomperz family, were involved in supplying the Habsburg army in Hungary.

The great amount of war news did not lead the editor Moushe to neglect other topics though. The paper contained a good deal of human-interest reporting, from natural disasters to accidents, as well as sensational news such as the birth of a child with two heads. This news generally came from abroad, but the floods in the northern part of the Dutch Republic and the great fire of May 1687 in Durgerdam (a village near Amsterdam) were also reported in detail. Remarkably enough there are also reports on disobedient monks and nuns, and even on miracles performed by a Roman-Catholic saint. Barring a few exceptions, the Kurant did not present its own Jewish community news, although of course, other newspapers’ reports on Jews did feature. Local Amsterdam news was absent, but the same was true of the Dutch papers. That was in part due to censorship. Burning issues were generally fought out in pamphlets.

Disappeared

Perhaps additional issues of the Kurant were published beyond the hundred in the collection, but there cannot have been many more. Moushe’s name first appears in 1686, and shortly after the last known issue of the Kurant on 5 December 1687 he started up his own printing press, first in the Netherlands and later moving to Germany. There are no indications that he took the newspaper with him or that others continued his work. The Kurant probably had too few subscribers. Perhaps the Ashkenazi community did not recognise itself in a paper that showed so little Jewish character. The world’s first Yiddish newspaper was not to be long-lived.

Illustration of an 18th-century Portugese Jewish funeral in Amsterdam

Illustration of an 18th-century Portugese Jewish funeral in Amsterdam© Bernard Picart/Wikimedia Commons

Except for one issue of a newspaper from 1781, shortly after the start of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War, no further Yiddish newspapers appeared in the Netherlands. Only halfway through the 19th century did Jewish newspapers with Jewish news appear in the Netherlands. In Eastern Europe, the Yiddish press started to flourish at that time.

David Montezinos, the man who happened upon the newspapers, died in 1916 and donated his find to Ets Haim. The collection survived World War II, but disappeared without a trace in the 1970s. It was supposedly transferred to the National Library of Israel in Jerusalem, but as far as is known it never arrived there. Fortunately, photographs had been taken before the disappearance, which are kept in Amsterdam University Library and are soon to be digitised.