There’s a Particle Accelerator in Salim Bayri’s Throat

Salim Bayri prefers working with materials that he’s never used before. Bayri was born and raised in Morocco and eventually ended up in the Netherlands via art school in Spain. Media, cultures and languages collide in his mutually diverse works of art.

There are multimedia artists who call almost everything they do a form of painting. According to Salim Bayri (Casablanca, b. 1992), a large part of his oeuvre is comparable to drawings; a medium that was long seen as something that was mostly suitable for preliminary studies. Bayri, however, cherishes the idea that a drawing can actually become anything. On his website, you can indeed click through his various projects via computer drawings, and it’s also delightful to simply browse under the heading ‘Drawings’.

However, he is by no means limited to one medium. For example, he makes large prints such as Smart_Shop.obj (2017), a collection of 3D models created by computer, which are in equal part reminiscent of a cabinet of curiosities as well as a souvenir shop. He also makes smaller cork ‘tiles’ that resemble a partially turned page, such as Nail, Carrot on a Stick and Alcachofa (all three from 2021).

This energetic and enthusiastic artist enjoys simply trying out things that are available to him. That could be a computer, paper and pencil, or even chocolate (The real thing is continuously somewhere else, 2020). The most important criterium is the possibility that something could go wrong.

Nail (2021, milled cork) & The Real Thing Is Always Somewhere Else (2020, chocolate bars, metal, wood)

Nail (2021, milled cork) & The Real Thing Is Always Somewhere Else (2020, chocolate bars, metal, wood)© Salim Bayri

Does Arabic Sound Solemn?

Bayri grew up in Casablanca where he attended a Spanish state school. There he learned about the history of a country different to his homeland; all knowledge that was of little use to him as soon as he left the building, he recalls with a laugh. What use was knowing about Spanish heads of state when he spoke Moroccan at home or watched French TV series?

But he was fond of this patchwork of languages and cultures, because it gave him the feeling that the world was much bigger than just him. It had to be possible to escape the limits of his own experiences and imagination. He now masters Moroccan, Arabic, French, Spanish and English, and is currently studying Dutch.

Coincidence soon turned out to be a rewarding way to escape one’s own limits. Going to art school was anything but certain, when Bayri – who had moved to Barcelona – wanted to study. Although he had loved drawing since he was a child, he had opted for a physics-oriented education in high school (why though should those two backgrounds be mutually exclusive?). In Spain, he wrote to several universities and educational institutions, and it was the Arts and Design school Escola Massana that took the bait. Otherwise, he might have become a psychologist, he notes. In 2019, he was admitted to the prestigious post-academic Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam.

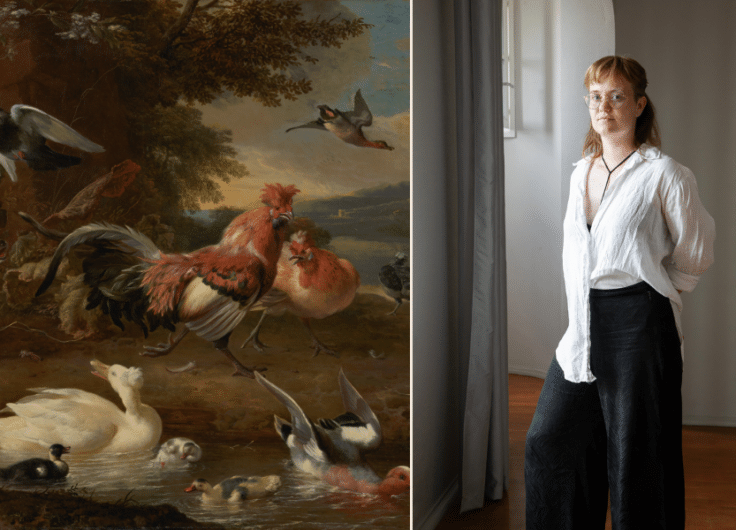

Corner Links, 2019, exhibited during the Rijksakademie Open Studios 2019

Corner Links, 2019, exhibited during the Rijksakademie Open Studios 2019© Mette Sterre

Residents of the Rijksakademie are expected to open their studios every year, during the well-visited Rijksakademie Open Studios. In 2019 he did so with Corner Links – a collection of objects he had created or collected over the past year. It included drawings, figurines, a photo he took in collaboration with his artistic colleague ‘G’s’, a 3D print of an artichoke, and even a baked loaf of bread the size of a door.

Corner Links, 2019, exhibited during the Rijksakademie Open Studios 2019

Corner Links, 2019, exhibited during the Rijksakademie Open Studios 2019© Mette Sterre

This repeatedly became the setting for his performance Every Now and Then, where Bayri himself would sit behind his computer, high up at the back of his studio, almost glued to the ceiling. He would then tell an improvised story about the various objects displayed below him, initially in English so that everyone could understand him. If he couldn’t come up with a word, he would switch to Spanish, for example, after which sometimes only two visitors would know what he was saying; something, which at times enormously amused both him and them. Language – and specifically the different levels of understanding language – had a huge impact on the audiences. For example, when he spoke Arabic, many onlookers seemed to mistakenly assume that he was saying something very solemn.

The Soul of the Machine

Audience reaction is important to Bayri – also in relation to his interest in technology. He emphasises that his main concern lies with the human aspects of technology. The software he uses is open source by definition; he only finds new devices interesting when they become available to a wide audience, so that diverse groups – Eastern, Western, rich and less well off – can come together in a shared technological ‘space’.

He is also interested in reactions to and stories about technology. As an example, he mentions the 3D printer, a tool he is fond of working with. They have been around for a few decades, but it was only in the 2010s that it looked like they would become mass-produced. This provoked some panic – just imagine that someone would print a gun. According to Bayri, these kinds of reactions form the soul of the machine, which gradually emerges. Accidents are also a part of this.

3D modelling software is also part of his artistic arsenal. Among other things, he made the first version of Sad Ali, an abbreviation of Sad Alien. This figure is perhaps the most striking constant in Bayri’s diverse oeuvre and has always been present in Bayri’s exhibitions, projects and presentations since his emergence. Sad Ali is a kind of comic book character, although he has hardly any personality. Bayri first thought of creating him after he heard about illegal aliens on the news and for a moment thought they were actual aliens. At the time, he was using modelling software to create pieces that looked solid, but were hollow inside.

That’s how he came up with the idea to create a character, half stranger, half alien – that literally has no inside. Yet many spectators bring their own interpretations to the minimalist Sad Ali, whom Bayri sometimes describes as a kind of search engine that only raises questions. As an artist, you can also escape yourself by outsourcing a significant part of the interpretation to the audience, who see their own backgrounds collide with the work of art.

Sad Ali, 2021, 3D-print made with bamboo and glue

Sad Ali, 2021, 3D-print made with bamboo and glue© Salim Bayri

Talking to the Software

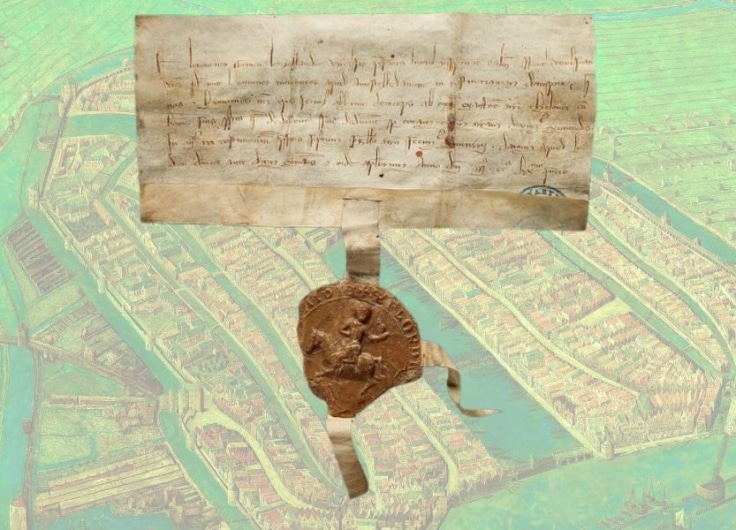

When I spoke with him, Bayri’s time at the Rijksakademie had just come to an end. For the second and final time, he opened his studio up to the public, which he had transformed into a huge installation called the Hadra Collider, a tipped hat to the Large Hadron Collider, a huge particle accelerator used to conduct physics experiments. Hadra is admittedly a self-invented word, but it contains the Moroccan word for ‘speak’, as well as the Arabic word for ‘procession’. Bayri wrote in the accompanying text about a ‘particle accelerator in his throat’, in which all the languages he speaks would collide.

The full installation consisted of some of his work from recent years – including drawings, of course – combined with various devices and a kind of mysterious control room. Bayri hopes to be able to further develop the project elsewhere, as understandably, he’s far from tired of it.

Hadra Collider, 2021, exhibited during the Rijksakademie Open Studios 2021

Hadra Collider, 2021, exhibited during the Rijksakademie Open Studios 2021© Salim Bayri

The Hadra Collider looks like – and this is definitely meant as a compliment – the work of a crazy professor from a cartoon; a classification that makes Bayri laugh heartily. He explains that his particle accelerator works with voice recognition software, which is set to English. Bayri speaks to it in other languages, after which the software tries to turn this into English words. He then responds to this.

In this way Bayri shows the violent tensions between languages: time and again words and languages clash, creating a feeling of displacement. But you can also view the installation more optimistically – as a metaphor for Bayri’s adventurous attitude: every confrontation offers new opportunities.