This is How the World Discovers Dutch Literature

Every year, hundreds of Dutch books are published in translation all over the world. For example, how does a Flemish novel get translated into Tamil, the fifth language of India? This is the result of a collective effort of all those involved. The commitment of the Taalunie

(Dutch Language Union) to the quality of translations is also essential. This is how it works.

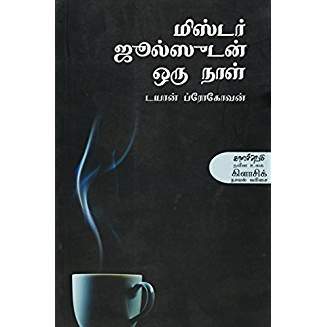

The cover shows a steaming cup of coffee against a black background. That much is certain. But what is the name of the book? Who wrote it? The writing is impossible to decode for someone who, apart from Dutch, knows a few European languages at most. Only on closer inspection does it turn out to be called MisTar juulsuTan oru naaL – the translation in Tamil of De buitenkant van meneer Jules (A day with Mr. Jules) by Diane Broeckhoven that was published in 2014 by the Indian publisher Kalachuvadu Publications.

The Tamil translation of Diane Broeckhoven's novel 'De buitenkant van meneer Jules'

The Tamil translation of Diane Broeckhoven's novel 'De buitenkant van meneer Jules'How does this book end up in the library of policy organisation Literatuur Vlaanderen (Flanders Literature)? In other words, how does a Flemish novel get translated into the fifth language of India?

From African to Swedish

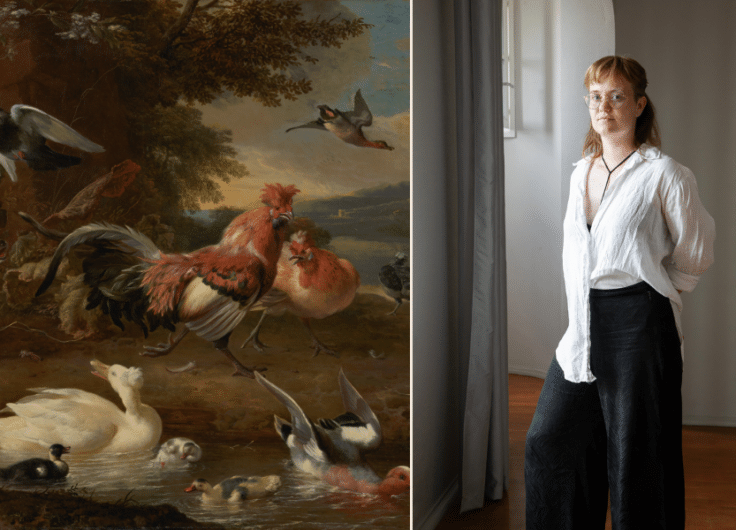

Every year, hundreds of books by Dutch authors appear in every imaginable language. In 2018, as far as the Dutch Foundation for Literature is aware, there were as much as 543. They concern all possible genres: novels by Arnon Grunberg, children’s books by Bart Moeyaert, classic books by Willem Elsschot, poetry by Maria Barnas, theatre texts by Jan Fabre, comic books by Typex, literary non-fiction by Midas Dekkers. This also concerns 45 different languages: from African and Amharic to Vietnamese and Swedish.

The English version of Willem Elsschot's novel 'Kaas'

The English version of Willem Elsschot's novel 'Kaas'The numbers are so large that you would think that all these books would end up on bedside tables of readers all over the world. It is not. Dutch is not a world language like English, Chinese or Spanish. Even Tamil has 3.5 times as many speakers. That makes it impossible for a foreign publisher to judge the quality of the book in Dutch. In fact, he might not even be able to figure out whether it is a thriller, literary novel or non-fiction book.

A peripheral language

There is a foreign curiosity to the Netherlands and Flanders, yet the current events in Washington, Moscow, and Beijing are more important in the eyes of the outside world than those in The Hague or Antwerp. The events in, say, Rio de Janeiro or Ankara also attract more interest. Foreign publishers are therefore more likely to want to read literature from those language regions.

In scientific terms: Dutch is a peripheral language. Native English speakers – most central language – therefore read relatively few books in translation, native Dutch speakers relatively many. No effort is thus required to translate books from English. The eager foreign publishers will buy the translation rights no matter what. However, in order to spread our literature around the world, other than with a lucky shot, targeted policies are essential.

From Frankfurt to London

The task of getting literature across borders has traditionally been for publishers. For commercial reasons, they promote their own publications to colleagues abroad. They always do this at book fairs: from the most famous ones in Frankfurt (October) and London (April) to the children’s book fair in Bologna (March). Dutch translators often act as sales representatives. They know Dutch-language literature, often like it and are eager to make it known in their own language area.

The Frankfurt Book fair

The Frankfurt Book fairThe specialised foreign rights agents, whom are increasingly employed by publishers, and translators, try to win foreign publishers over with quality. They also know the funds of these companies and can therefore assess whether Herman Koch, Annie M. G. Schmidt or Leonard Nolens fits in. That is not the only argument. High sales figures, literary prizes, and a local link are taken into account. For the latter reason, Koch’s regular Finnish publisher would like to have his Finse dagen (Finnish days).

‘De Avonden’ in English

However, it cannot be left to the market alone. The Netherlands has had the Foundation for the Promotion of the Translation of Dutch Literary Works since 1954 – now incorporated into the Dutch Foundation for Literature. In Flanders, the Flemish Literature Fund – now Flanders Literature – has adopted a structural approach on foreign promotion since 2003, after some occasional efforts. Both institutions work hard to promote all kinds of Dutch-language literature. This also includes classics or different genres.

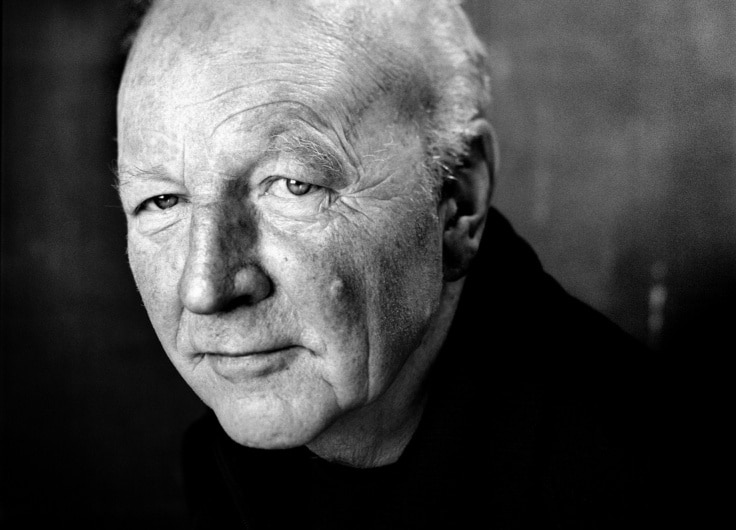

The English version of Gerard Reve's novel 'De Avonden'

The English version of Gerard Reve's novel 'De Avonden'How else would De Avonden (The Evenings) by Gerard Reve have appeared in English four years ago? And around the same time, in another handful of languages, such as Danish, Hebrew and Turkish? Publishers would give priority to more commercially interesting titles. They might have also thought: this novel is too typically Dutch. It was only through a well-considered commitment to the title that the London-based Pushkin Press decided to take a chance. And guess what? British critics read Sam Garrett’s translation and discovered a classic with universal eloquence.

Of course: money

The two funds have available a wide variety of political resources. They visit fairs, such as those in Cairo (February) and Guadalajara (November). They also invite foreign publishers on publisher tours to get to know our local publishers. They make test translations (in the language that most people speak: English), compile brochures, award prizes to translators, send Dutch authors to festivals or on promotional tours around the word, and so on.

The most important resource is, of course, money. Both funds make translation grants available in order to limit the economic risk of translating an often still-unknown author. The subsidy covers a maximum of 60% (Flanders) or 70% (the Netherlands) of the translation costs, but can be as high as 100% if it concerns a classic. This is widely used. One third of the 543 translations from 2018 are subsidised. Kalachuvadu also received support for Broeckhoven at the time: 435 euros.

Approved translators

The translation must be of a certain quality. The Dutch Language Union plays an essential role in this. Thanks to its widespread support for Dutch language courses worldwide, the organisation contributes first and foremost to ensuring that, again and again, there are enthusiastic translators everywhere. Through the Centre of Expertise for Literary Translation (ELV), co-founded by the Dutch Language Union, investments are made in talent development and in promoting the expertise of these translators. To this end, the ELV organises, amongst other things, courses and seminars.

In order to guarantee quality, publishers can only receive translation grants for accredited translators. At the end of 2018, 690 translators were on that list, translating into 33 different languages. With regard to getting on that list, they have to submit a test translation that is evaluated – anonymously – by professional translators and/or teachers of translation science. If the test translation submitted by a publisher is not successful, the funds will nominate another, approved translator.

Anandh Krishna, translator of Diane Broeckhoven, is not on that list. Why is that? He is not proficient in Dutch at all. He translated the novel from English due to a lack of Dutch-Tamil translators. And that translation was judged on quality. Readers in the Tamil-speaking part of India can therefore read MisTar juulsuTan oru naaL in the knowledge that they get a faithful impression of this pearl of Dutch literature.

This article was previously published in Dutch on the website of the Dutch Language Union.