Thriving in Babel: Plea for a Multilingual Europe

‘We have no choice, certainly in Europe, but to become as multilingual as possible. If we want respect for our own language, we must also show respect for other people’s languages.’ Luc Devoldere, editor-in-chief of the Flemish-Dutch cultural institution Ons Erfdeel, made an impassioned plea for multilingualism during a conference on education in Belgian and Dutch Limburg, which was held in Maastricht on 13 and 14 March. According to Devoldere, we should all be able to understand at least one other language besides our own mother tongue and the lingua franca English. With their tradition of relative multilingualism, the Flemish and Dutch could take the lead in this in Europe. Read the complete lecture below.

Multilingualism is a blessing. Multilingualism is a curse. Multilingualism is a challenge.

First the curse.

The Bible is clear. Once upon a time, humankind spoke one language, a single protolanguage. And there was peace and unity. Everyone understood everyone else. Then humankind became proud and arrogant, so God punished them with a “confusion of tongues” – another expression for multilingualism.

Lost in translation. We are all familiar with it, you don’t need to be standing in the street in Tokyo, desperate because you can’t read a single sign or understand anybody. If everyone around you is speaking a language you don’t understand, you are literally excluded, an outcast. Language is power. There is always a power relationship involved in languages. Language struggles do exist.

Multilingualism is a blessing too. Every language expresses reality differently and therefore contributes to genuine diversity, true pluralism. When a language dies, the world becomes poorer. Those who speak or understand several languages, live more lives, develop more perspectives of reality, are more able to penetrate other cultures and people. They may even become more empathetic. They certainly become richer. When I speak French, I become someone else.

Multilingualism is a blessing AND a curse, but above all, it is a challenge, an effort, not an idyllic walk in the park. In the world we live in, and certainly in Europe, we are condemned to multilingualism, we are called on to speak as many languages as possible. But it is not simple. Not everyone will succeed.

We know that we should start learning other languages as early as possible; we also know that we can only expect respect for our own language if we respect other people’s languages. Furthermore, there on the horizon, like the raft of the Medusa, the saving grace of the lingua franca looms amidst the cacophony and confusion of multilingualism. Let me be clear, a lingua franca, a vehicular language, a language that maximises mutual understanding and communication, is both useful and necessary.

For centuries, Latin was the lingua franca in Europe. It was often denounced as elitist, but people forget that everyone had to learn Latin as a foreign language. It put all those who spoke it on an equal footing; no European nation could feel disadvantaged by Latin. That will never again be the situation.

In the seventeenth century French took over the role of Latin as the “glamorous language”, the language of the Court of Versailles and the salons, international diplomacy and, later, the Enlightenment. Until at least 1918, and till the 1950s in Belgium, the French language enjoyed considerable status, and therefore power.

Today, however, English is the lingua franca of Europe and practically the entire world – or at least the sort of English that is spoken and written by non-mother tongue speakers. So, English is necessary. But equally, it is not sufficient. Yet I have the impression that multilingualism is often reduced to speaking and writing English. Monolingualism is not multilingualism though – certainly not in Europe, a continent where linguistic diversity is an essential characteristic, and as such is embedded in its credo, its DNA. Those who promote only English as a lingua franca, the language of science and education, condemn the other languages to loss of function, to being nonentities, in the longer term.

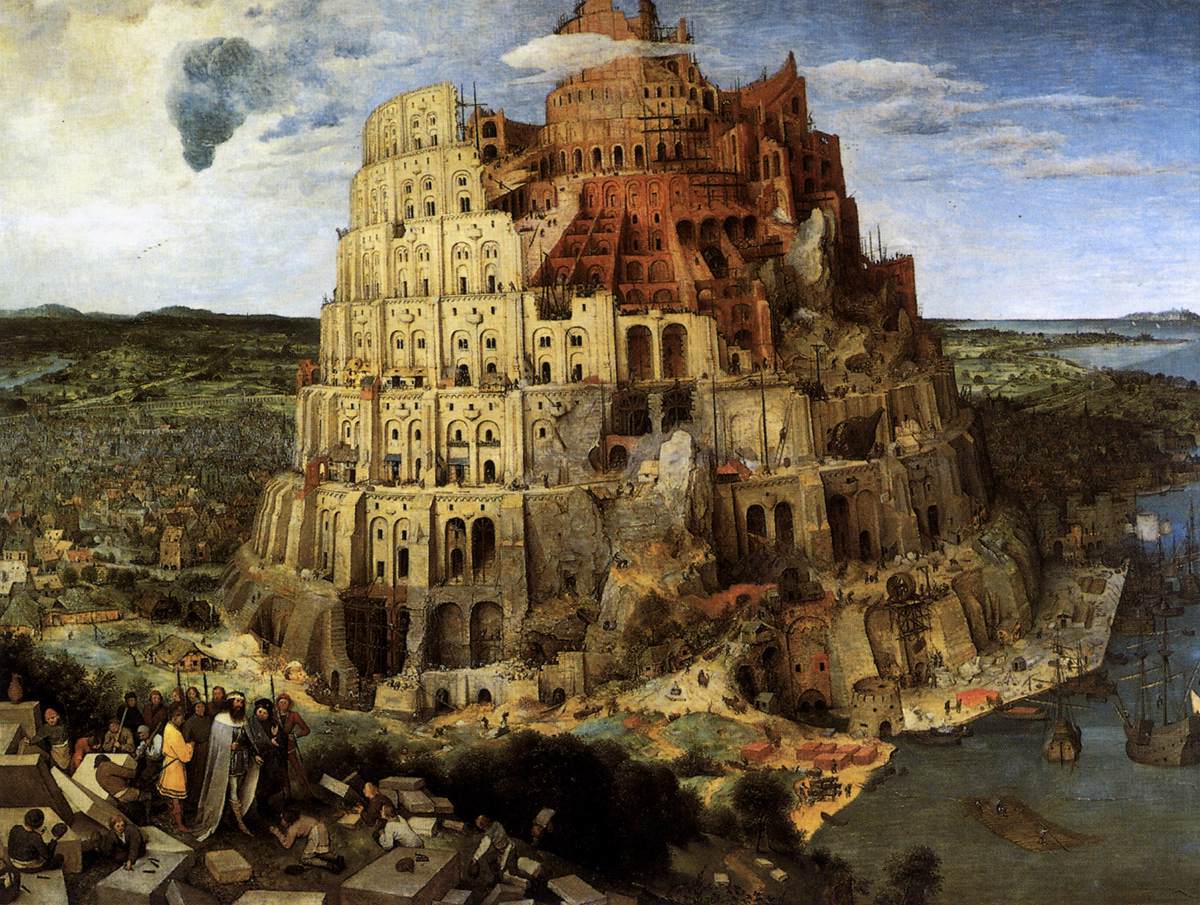

The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563

The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, c. 1563© Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Language and territory

I am opposed to linking language and ethnicity, Blut und Boden

you might say. I would prioritise the concept of “territory”. Territories exist within borders, and borders protect. You can only transcend them if you accept them. Obviously, they are contingent, they could have lain elsewhere. But they are where they are and idly meddling with them risks opening a Pandora’s box.

It is worth saying perhaps, that when it comes to language use in the public sphere, one cannot continue to disregard a given territory with impunity. If only for the fact that a representative democracy cannot function properly with more than one language. As the British philosopher and economist John Stuart Mill wrote in 1861, ‘Among a people without fellow-feeling, especially if they read and speak different languages, the united public opinion, necessary to the working of representative government, cannot exist.’

Obviously, we are going to have to learn to live – probably increasingly – with territories where more than one language is spoken, on the street and at home. Nonetheless, we shall have to continue to combine that with a conscious choice for one official language in the public sphere of that territory. The principle of territoriality as opposed to the principle of personality and the ius gentium. Proponents of the latter consider that you should have the right to speak your own language everywhere: English and French in Canada, Dutch and French in Belgium, and French, German or Italian in the whole of Switzerland. Sometimes they want to compromise the principle of territoriality with Blut und Boden. They are mistaken. In his study Linguistic Justice (Oxford University Press, 2011), Philippe Van Parijs demonstrates clearly that the principle of territoriality is legitimate compensation for what he considers to be the necessary existence and use of English as a global lingua franca. Today, Belgium is officially a trilingual country, but that does not mean you can speak Dutch, French and German everywhere. In Belgium, language is actually linked to territory, except for the officially bilingual capital, Brussels.

Because I am Belgian, I begin any exchange in Brussels in my own language, Dutch. That is my right. Then I see what happens. As an adherent of the principle of territoriality, I stand up for legality. But legality alone will never be enough. One must also be courteous. Legality without courtesy is inflexibility. However, courtesy without a legal framework means you always forfeit the initiative. It takes two to tango. It is no different in the offices of the public authorities. Civil servants must respect the legislation (Dutch is the official language in Flanders), but they must also do everything to ensure successful service. They must act within the law but also be courteous. ‘Fortiter in re, suaviter in modo’, says the Latin motto, gentle in manner, resolute in deed. While we’re quoting, here is another one from Lacordaire, a good guiding principle concerning legal certainty, ‘Between the strong and the weak (…) it is liberty that oppresses and the law that liberates.’

Multilingualism

Multilingualism always starts with a mother tongue. Those who renounce their own language, change their identity, claimed Emil Cioran, who chose to write in French, they commit heroic betrayal. For writers it means writing a love letter with a dictionary beside them. Strangely enough, Cioran once admitted that real writers confine themselves to their mother tongue. They do so in self-defence, because there is nothing more destructive of talent than too much openness of spirit. To top it all, he claimed that when a nation no longer believes in its own language, when it ceases to think that its own language is the supreme form of expression, the very essence of language, it has fallen into total decline.

In contrast, the Dutch sociologist Abram de Swaan dismisses language sentimentalists, who identify language with the group and want to maintain the cohesion of the group by maintaining the language. ‘The language community can be very limiting and suffocating’, says de Swaan. Well, one can avoid suffocation by unabashedly standing up for one’s own language, and in the same breath deliberately linking its use to multilingualism. We have no other choice than to become as multilingual as possible, certainly in Europe. Demanding respect for one’s own language requires showing respect for other people’s languages. At the request of the European Commission, the French-Lebanese writer Maalouf wrote a report with other European writers and intellectuals, in 2008, in which he advocated that every European should choose another European language to learn and cherish besides their own and English. He referred to it as a “personal adoptive language”. (See A Rewarding Challenge. How the multiplicity of languages could strengthen Europe, Brussel, 2008). For his part, Umberto Eco stressed the importance of the translation culture with the surprising quip, “The language of Europe is translation.”

There’s more to you

With their tradition of relative multilingualism, the Flemish and Dutch could take the lead in Europe in advocating for multilingualism. Multilingualism should bring some balance to the dominance of English. Obviously English is necessary, but it is not sufficient. That should be the guiding principle of an achievable European language policy. We should not fight against English but nurture other languages besides English. Because English is so dominant in our lives, and certainly in young people’s, I would even dare to suggest, though I have few illusions about it, that the first foreign language in schools in Europe should not

be English. Which language should be the first foreign language depends on geographical and cultural factors, our geostrategic position, you could say, our destiny.

But I am level-headed enough to realise that English is, in fact, the first foreign language almost all over the world.

For Flemings, the first foreign language is French and, in my opinion, it should remain so, because French resounds in our Dutch, because it has contributed to forming our history and culture, and because we are confronted with it all along our southern border. By reason of their proximity, English and German should also continue to be important languages throughout the Low Countries. You cannot be surrounded by these huge language regions with impunity. In Flanders, then, we should prioritise French, English and German, in that order. If you are Dutch, make that English, German and French.

Yet in Flanders knowledge of French is declining, while in the Netherlands knowledge of French and German have almost disappeared. I think that is a pity. We are losing our relative multilingualism. And no, I do not think that it makes sense to teach Chinese in our primary and secondary schools.

I will focus now on the border areas and, in particular, on the border that I know best, the border between Flanders, Belgium and France – Southwest Flanders and the northern French department of Nord, or the cross-border metropolis Kortrijk-Lille-Tournai.

In border areas it is not only states that confront each other but languages too. The principles of linguistic justice apply here. Respect for each other’s territory and therefore also the principle of territoriality. At least in the public arena. In the best case the principle of reciprocity. If French people come over the border, they often bring their language with them into shops, petrol stations and the public authority offices. Why then can Flemings not do the same in France? The relative power of the two languages still plays a role here.

Take education. The language of education and therefore that of the playground (which actually belongs to the “public sphere”) is by definition the language of the territory.

So, let’s first look at the legality model. Only then can we apply the courtesy model (with regard to the home and street language). In an ideal world the two would be engaged in a dialectic. How should languages interact with each other in a border area?

Let’s look at the practice in the Eurometropolis.

In an official context it is symbolically important to treat both languages with the same respect. That means that during official exchanges both partners speak their own language and simultaneous interpretation is provided. But obviously, this is not possible in other, ordinary contacts.

The French have introduced the concept of “courtesy Dutch”. With a set of a few dozen words and expressions one can break the ice and show one’s goodwill. I do not underrate this strategy, this captatio benevolentiae, but the democratic deficit remains, and the strategy is at the most a stepping stone.

In the medium and long term, it seems to me that only one model is feasible, although it will demand effort from both partners: the model of the listening language. One reads and understands the other’s language but does not speak it.

In contacts, meetings and debates everyone speaks their own language, but they are able to understand the other’s language. The advantage of this practice is that it eliminates the reticence, fear and scruples about having to communicate in a language one speaks less well. It puts both partners on an equal footing in conversation and discussion, which is a fundamental democratic requirement. This is linguistic justice.

To achieve this model in the medium or, I fear, the long term, the centralistic, Jacobin education system in France would have to be decentralised. By this same principle of geographic proximity, Spanish should be promoted in Perpignan, German in the Alsace, Italian in Nice and Dutch in Nord – and always as the second foreign language, after English. At the moment that is definitely not the case. Spanish, for example, is very strong in Nord.

I repeat that this is a matter of conscious language policy, which in Nord should positively discriminate in favour of Dutch. If France is serious about the Eurometropolis, about good neighbourliness in Europe, it will have to invest more in learning the language of its next-door neighbour, out of well-considered self-interest too.

For its part, Flanders should bring its economic power to bear here in this border area, precisely because the power relationship between the French and Dutch languages has remained disadvantageous for Dutch. It’s the economy, stupid.