Those who think the drop in reading skills can be tackled by offering young people in the Netherlands and Belgium popular books filled with suspense and action on TikTok are setting themselves up for disappointment. Reading levels can only be boosted with texts that appeal to the imagination and improve linguistic ability. Draw the target group in with the things they know and love, and send them out with something that provides friction, writes Dutch literary education expert Jeroen Dera.

If the decline in reading were a spectre, like Janus, it would have two faces. On the one hand, over time we see less reading of books for leisure, a phenomenon that has spanned generations. By that definition the decline in reading is more or less equivalent to a reduction in reading frequency. On the other hand, at least in the media, the concept has gradually come to refer to declining performance in reading, and hence goes hand in hand with debates on low literacy levels, education and equal opportunities. When a decline in reading is mentioned in relation to the dramatic PISA scores of Dutch and Flemish 15-year-olds, the issue is not so much reading frequency as reading ability.

Of course those are concepts that interact substantially. Research by John Jerrim and Gemma Moss, for instance, shows that anyone who regularly reads a book, and more specifically a work of fiction, scores better on tests of reading skills. As so often this is a case of communicating vessels: those who score high in reading tests are also more inclined to read books. If we picture the spectre of declining reading as a two-faced monster, it clearly resembles Janus.

Texts that give pleasure are not necessarily suited to the task of improving reading skills

For promotors of reading, that Janus head invokes a moral dilemma. Those wanting to ensure that non-readers or reluctant readers still open a book once in a while tend to tackle one of the Janus faces, improving reading skills. In order to deal with the other face, they will have to work on fulfilment in reading, as in the absence of severe coercion, reading frequency will only increase along the bumpy path of pleasure.

Texts that give pleasure are not necessarily suited to the task of improving reading skills. Of course in a society in which a considerable proportion of the electorate seldom or never read, it is always a clear win when non-readers in large numbers pick up formulaic thrillers that afford them an absorbing reading experience, but that will not tame the monster. The spectre will only be fully beheaded when we focus not only on reading frequency but also on reading skills.

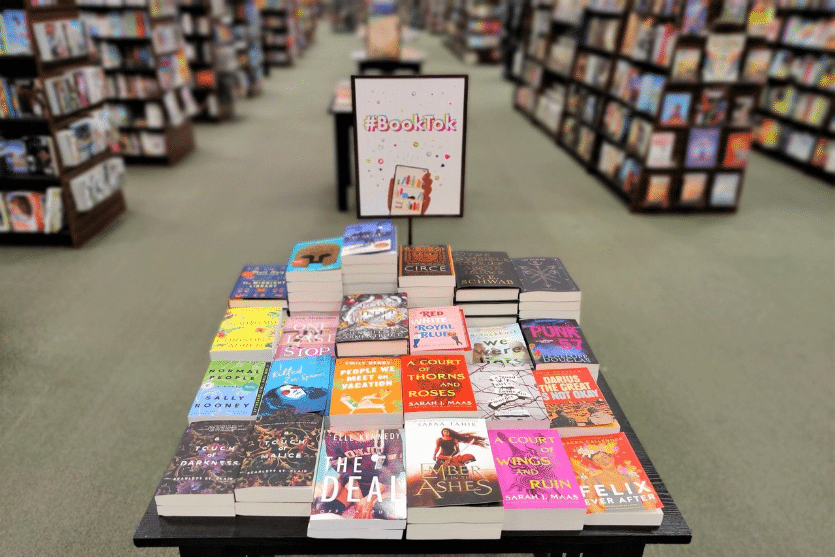

Books on display that are popular on #BookTok, a subcommunity on the app TikTok that focuses on books and literature.

Books on display that are popular on #BookTok, a subcommunity on the app TikTok that focuses on books and literature.© Barnes & Noble

Learning to read well, as emphasised by the Swedish literary scholar Maria Nikolajeva, a professor at Cambridge University, is achieved with texts that resist decoding, texts that demand cognitive work, that appeal to the imagination and linguistic ability. Many texts situated at the heart of young people’s literary culture in the year 2024 barely fulfil Nikolajeva’s condition, if at all. Ana Huang’s Twisted series, Hannah Grace’s Icebreaker, or the Dutch titles Museumnacht and Happyland by Chinouk Thijssen: these are not texts that resist decoding, so they are not the type to improve reading skills needed to function in the complexity of today’s information or rather disinformation society.

Learning to read well is achieved with texts that appeal to the imagination and linguistic ability

Most promotors of reading are aware of that and focus firmly on what are called “rich texts” – texts that are “rich” in content as well as form. At the same time, in order to reach their readership they are just as willing to use material that scores well among their target group, who, according to a recent survey by the Nijmegen literature student Alicia Anthonise, described reading in Dutch as “cringeworthy”. So libraries and cultural institutions organise book events (advertised with the English name) in which they present young people with whatever is doing well on the American-oriented #BookTok – from young adult works to romance and fantasy.

Bibliotheek Schiedam, for example, recently organised a pizza session to attract young people and explore with them how they could get them into the library more frequently. The conclusion was that they should focus on books filled with suspense and action and on activities such as creative writing, as young people would particularly like to “do” something when in the library. In some, that will undoubtedly influence reading frequency, but reading skills do not directly benefit.

It may have been a telling sign when the young people who had taken part in the pizza session received a gift voucher and asked warily if they had to spend it on a book. On the library’s website the organisation writes: “The relief when they hear that they can choose what they spend the voucher on. After all, they can borrow a book from the library!”

In taking this stance when working with young people, promotors of reading resemble the cultural mediators of the 1930s, who hoped to raise the “masses” through a step-by-step model. If in popular radio we merely pay attention to detective novels, thus tempting the listeners towards light reading materials, then they might eventually arrive at the lofty heights of Arthur van Schendel. If we wish to slay today’s two-faced monster of declining reading, we can’t afford an attitude like that. Promotors of reading need to do something different: pleasure, as defined by the target group, must be found at every rung of the ladder, but so must “resistance to decoding”, to quote Nikolajeva once again.

© Pexels / Tima Miroshnichenko

So how does that look? Every afternoon or evening a library devotes to young adult writers on #BookTok must not only focus on what is popular but also on rich texts that could be popular. In concrete terms, don’t place Chinouk Thijssen beside Laura Diane, as De Nieuwe Bibliotheek in Almere did, but beside Edward van den Vendel, whose classic 1999 young adult novel De dagen van de bluegrassliefde (The Days of Bluegrass Love) would not be out of place amidst the queer fiction so popular within the subculture formed by #BookTok. Or organise a debate on the diversity of literature written in Dutch and alongside Noah de Campos Neto, who has more than 27,000 followers on TikTok and fervently proclaims the lack of diversity in Dutch literature, invite Sabrine Ingabire, who in her debut novel Lotgenoten (‘Peers’) captures the voice of an ethnic minority teenager who will appeal to the imagination of many young people, but who cannot compete with the popularity of Adam Silvera and Taylor Jenkins Reid.

The rule of thumb for responsible programming should be to lure the target group in with something they know and love, and send them out with something that provides friction, something that demands decoding, but that also resists it. Because however high some young people’s reading frequency may be, if they are swimming en masse into the net of algorithmically promoted formulaic fiction, the spectre of declining reading skills mercilessly turns its other face.

Lure young readers in with something they know and love, and send them out with something that provides friction, something that demands decoding, but that also resists it

At the end of last year when the fifth part of the wildly popular Heartstopper series was published, many book shops organised a launch event. Fans spoke, people discussed the Netflix adaptation and there were communal readings, accompanied by crisps and fizzy drinks. Every promotor of reading knows, if they put Heartstopper on the programme, the entire room will be full of eager teenagers, but do they also know that the main character Charlie has a poster on his bedroom door of Evelyn Waugh’s classic Brideshead Revisited? And does every promotor of reading know that Isaac, the character from the Netflix series who is even pictured reading a book at the bowling alley immerses himself in Kate Chopin’s Awakening and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s Le Petit Prince? Those truly wishing to combine pleasure in reading with the advancement of reading skills, thereby feeding both mouths of the Janus head, should note precisely these points – so that all fans of Charlie and Isaac also go on to read like them.

This opinion piece is a reworking of a keynote lecture which Jeroen Dera gave in Ostend during FAAR, The Low Countries’ non-fiction book festival (7-9 March 2024).