Philip the Bold and his wife Margaret ruled Flanders for twenty years from 1384-1404. During that time they would expand their family’s rule into Limburg, as well as set their successors up to rule Brabant, Holland, Zeeland, Hainault and other low country territories. The manner in which Philip trod this treacherous path, in particular his giving of lavish gifts and making steady and long-term alliances, would set the tone for a dynasty that was going to contribute so much to the emergence of a lowland culture and identity.

Being the easternmost of the Low Countries, Guelders was more intertwined with the vagaries of both the German Empire, the major bishoprics of Cologne and Munster, but also with the Hanseatic trade network, than say Holland or Brabant. In the 1370s it had a succession crisis of its own, and erupted into civil war when the Duke, Rainald III and his brother had both died without issue, and left two sisters and their husbands to fight it out. Two main factions had emerged, the Bronckhorsters and the Heekerens. Out of this, in 1379 William of Guelders and Juelich, supported by the Bronckhorsters, came out on top with a shaky regime. He was supported by the Holy Roman Emperor, but could not fully placate some of the cities in his domain, or an opposing noble faction that remained from the civil war.

Holland was also engaged in an on-again, off-again civil war of its own, the so-called Hook and Cod wars. The victor of that war’s first phase, William V, had taken over his mother’s domains in Holland and Zeeland in 1354 and then Hainault upon her death in 1356. Soon thereafter, he began to show signs of insanity and was soon consigned to being locked in a castle, and his younger brother, Albert, took over the regency of Holland, Zeeland and Hainaut.

Albert oversaw half a century of relative stability in Holland, supported by and supportive of the Cod faction, which largely represented the burghers and urban elites in the cities. The tensions never truly disappeared, however. The Hooks, being mainly various nobles who did not support him, would go to extreme lengths to stop Albert being absolutely in bed with the Cods. And I mean literally in bed. In the mid 1380s Albert, known for his frivolous fancy for females, became involved with a lady called Aleida van Poelgeest. This became a catalyst for another eruption of the civil war. Aleida, a member of the Cod faction, was seen by the Hooks as gaining too much political influence over Albert, and she would be assassinated by them in 1392. The brutal revenge this evoked from Albert saw Hook supporters having to flee for their lives as he sought to punish those responsible, as well as took the opportunity to settle a few political scores. So Holland, although nowhere near as populated or wealthy as Flanders, was beginning to show echoes of the same kind of unrest which had plagued that province.

Luxembourg was very much under the thrall of feudalism; the house of Luxembourg had gone way beyond the borders of their low-country domain and by the late 14th century were one of the two most powerful houses in the German Empire and, at this stage, the Emperors, as well as kings of Bohemia.

Friesland was being Friesland, full of Frisians, feeling free, but fighting themselves in their own factional dispute between the Vetkopers and the Schieringers.

Joanna, Duchess of Brabant (1322-1406), by Pieter de Jode, circa 1663.

Joanna, Duchess of Brabant (1322-1406), by Pieter de Jode, circa 1663.© Wikipedia

Lastly, Brabant and Limburg were ruled by the Duchess Joanna. She and her husband Wenceslau, who was the brother of the Emperor and one of Luxembourgers, had made a series of Joyous Entries into Brabantine towns in the 1350s as the new Duke and Duchess, and signed documents that affirmed the rights of the Estates of Brabant. But shortly after that, the Brabant War of Succession began as Joanna’s sister Margaret and her husband, the Count of Flanders Louis of Male, took gumption at the idea of Brabant passing to the House of Luxembourg. They had garnered enough support to block the possibility of that happening should Joanna and Wenceslau bear no heirs or successors.

In the War of Brabant Succession, Flanders had taken chunks of Brabant, such as Antwerp and Mechelen. Even though Joanna and Wenceslau remained in power, they did not, in the end, have any children. So the question of who would inherit the titles to Brabant, Limburg and an area called the Overmaas from them continued to be a thorny issue which, by the 1380s, concerned the rulers of Flanders, the Imperial Luxembourg family and the nobility and urban elite in Brabant who had concocted the terms of the Joyous Entry.

Marriage of the Millennium

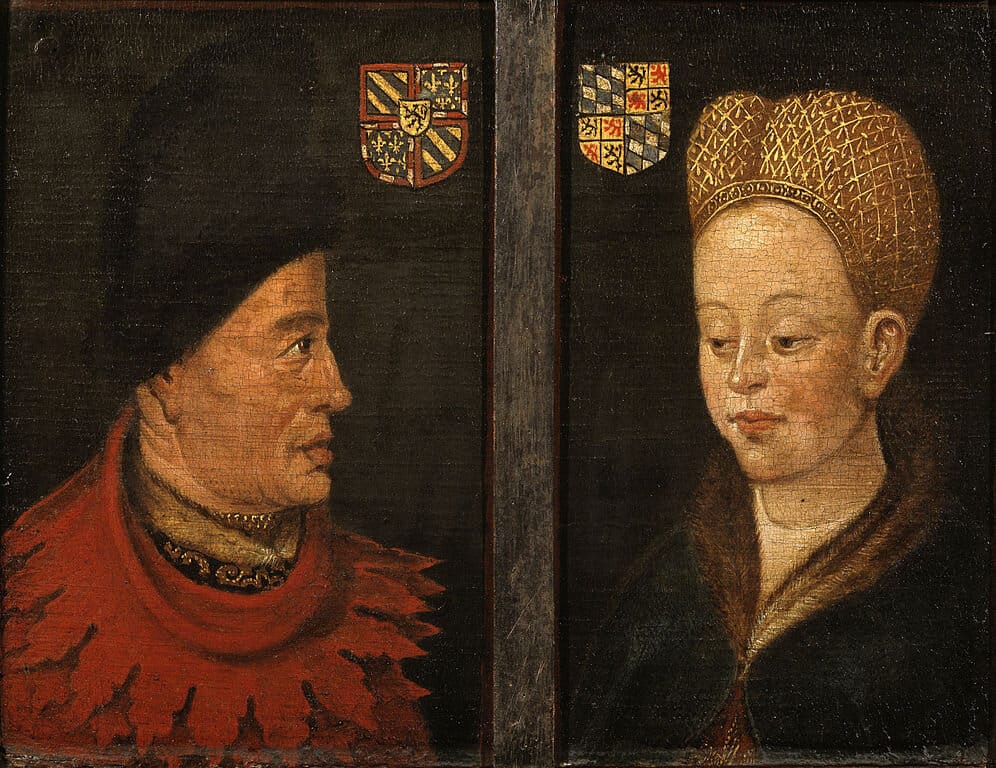

Philip the Bold was a wedding planner, and a rather ambitious one, at that. Particularly regarding a double marriage that he arranged that took place in 1385 at Cambrai. The wedding was of his and Margaret’s children to those of the Regent of Holland, Zeeland and Hainault, Albert and his wife, who of course was also called Margaret cos, you know, why would you want to make story-telling easy by giving different names to different people?

Portraits of John The Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria, by unknown

Portraits of John The Fearless and Margaret of Bavaria, by unknown© Wikipedia

This wedding was a statement as to what Philip’s rule would look like. Firstly, it was a brilliant act of diplomacy that connected the two largest dynasties in the Low Countries. His son and his daughter, John and Margaret of Burgundy were 13 and 10 respectively. Albert’s children, the siblings William and Margaret of Bavaria, were aged 20 and 22. So by our modern standards this was all-out weird, but for the standards of this medieval high-nobility, it meant that their eventual progeny would inherit, on the Burgundian side, Burgundy, Artois and Flanders, and on the Bavarian side, Holland, Zeeland and Hainault. As Wim Blockmans puts it:

‘With the weddings there emerged a peaceful alliance between the two most powerful ruling dynasties in the Low Countries, and through them it united spheres of influence in the German Empire and in France.’

It meant that the Valois-Burgundian dynasty which Philip had begun would be able to expand beyond Flanders in the future, and the groundwork could be laid for a centralised proto-state. That is not necessarily what Philip or anybody else was thinking about or aiming for, however. Like every other character in the saga of family feudalism in the Low Countries, Philip was simply making moves to better his family fortune. The difference is that he just had overwhelming success at it.

Portrait of Philip the Bold (1342-1404). Later copy of a lost late 14th-century painting from the Chartreuse de Champmol near Dijon.

Portrait of Philip the Bold (1342-1404). Later copy of a lost late 14th-century painting from the Chartreuse de Champmol near Dijon.© Wikipedia

The wedding was lavish, incredibly expensive, and defined by pomp and splendour. Despite the fact there was at least a ten year age gap between the members of each couple and that two of the four involved were still children, it was important for Philip to make it as extravagant as possible. Not for the benefit of the couples, however, but for the benefit of his own prestige. He had to legitimise the growth of his power. His nephew, the king of France, turned up, and so much of the splendour was reserved for his grace. Other guests included foreign dignitaries as well as many counts, dukes, lords and other princes from both France and the Empire. The whole thing lasted for a week. After the actual ceremony on the first day there was a great feast, during which the king of France and the newlyweds, along with their mothers, were fed by other lords and great lords sitting atop their horses. It pays to be king. And for the Duke of Burgundy and the Regent of Holland, it paid to just…well pay.

Albert, as one of the two fathers of the brides, is said to have spent as much as an entire normal year of Holland’s income to pay for his part. Philip, in his position as regent of France, was in charge of a whole lot of cash. He was able to spend four times as much, over half of which was spent just on gifts that he gave people, who he had targeted for making a benevolent relationship with. It was a rousing success, as through the wedding Philip was able to pull people to him and his family’s cause, now joined with the House of Bavaria, and he glued them there by spending an absolute fortune on being generous. From the wedding on, Philip was the undisputed big-shot in town.

Brabant and Guelders get feisty

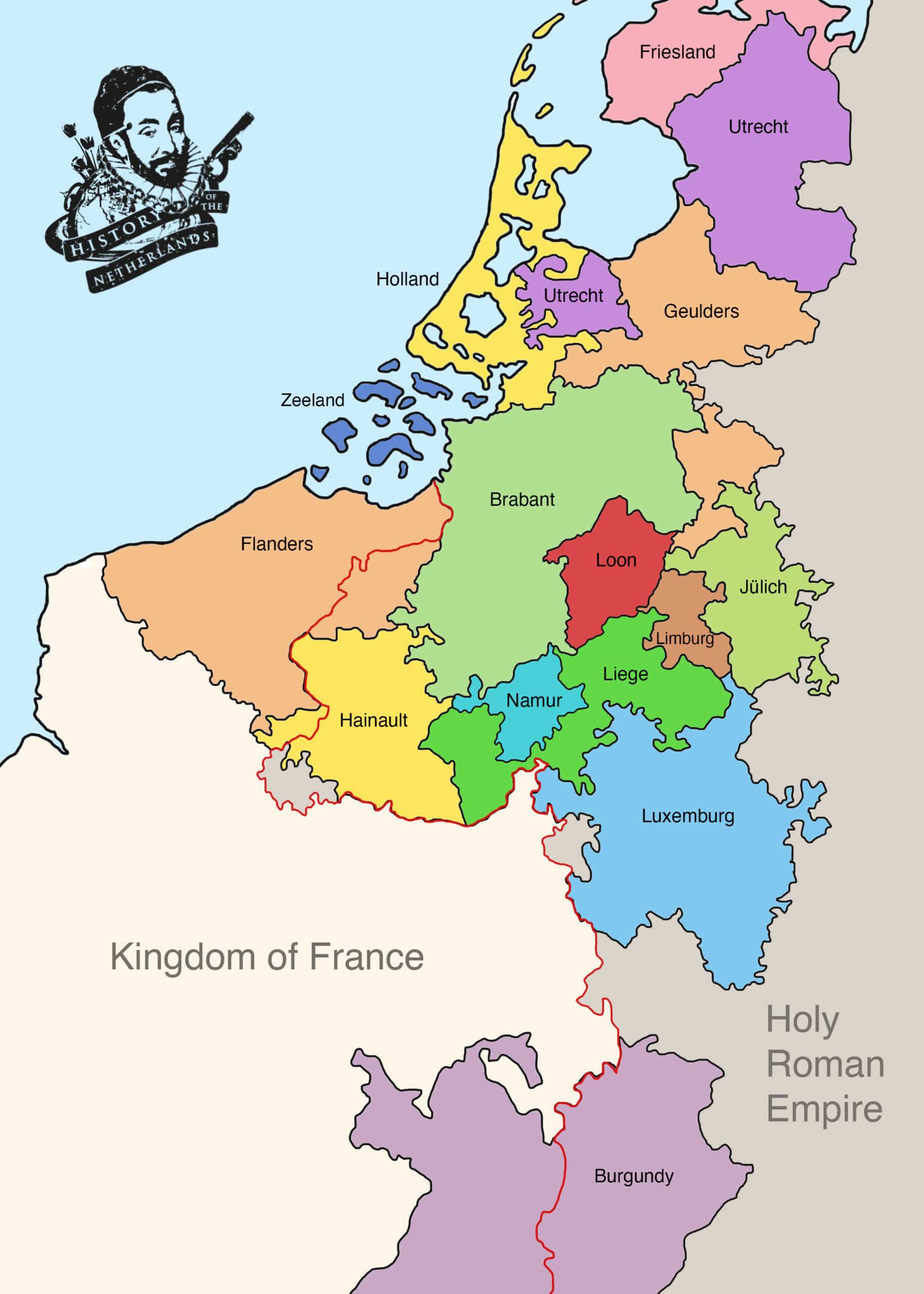

Map by David Cenzer

Map by David CenzerIn the same year as the wedding, Joanna, the Duchess of Brabant, was confronted with a military and economic nuisance in the form of Guelders. The Duke of Guelders, William, who had come out victorious in the civil war there, now turned his attention to towns and areas in a region called Overmaas. William’s father ruled the County of Juelich, to which these domains had formerly belonged, but which now belonged to Brabant. With an eye to his future inheritance of Juelich, William wanted them back. To these ends, in 1385 he asked for negotiation with Brabant, but these amounted to nothing. Brabantine forces were sent to bring Guelders down a notch, but in response William took the town of Grave, situated in the north of Brabant, on its border with Guelders. Its strategic location on the Meuse river meant that he could use it to launch raids and invasions into Brabant. If he could take it.

And taking it turned out to be pretty simple indeed when the son of the castellan of Grave betrayed his father and allowed William’s army in. At this point, William could probably have sought negotiations with good terms, including keeping the town, to solidify his advantage. Instead, he continued a policy of aggression and formally declared war on Brabant on 14th September, 1386.

As you might imagine, Johanna responded to this by raising her banners and calling the militia of Brabant to her cause, and set about putting Grave to siege. The force assembled for this task may have been larger than William expected. Even though he had prepared the town for a siege, after not very long he sought a negotiated settlement, which was handled by the regent of Holland, Zeeland and Hainault, Albert, who had just benefited so much by marrying his children off to Philip the Bold’s.

William of Guelders and Juelich (1393-1402)

William of Guelders and Juelich (1393-1402)© Rijksmuseum

On the 21st of September, William and Joanna agreed to abide by whatever Albert decided in the conflict, and on the 26th of September both settled on the terms he set out, which essentially put everything back the way it had been. Both parties packed up their stuff and went to move out.

Except that sneaky William, instead of leaving, waited for Joanna, her retinue and forces to leave, then just further provisioned the town of Grave, built up its defences even more, and refused to release his prisoners. He gave a figurative mooning to the conventions of medieval conflict mediation. Joanna, in what has been described as ‘disappointment’, sought assistance from Albert. She was probably hoping for help of the military kind, however he continued on a path of diplomacy and negotiation, which was going nowhere.

Enter the Bold one…

Joanna, caught in a bind and needing someone with money and fighting forces, turned to her brother-in-law, Philip the Bold. Philip showed he was a trustworthy ally and gave her the support needed. He had no doubt already assured her that, was she to ever require such assistance, such assistance would be given.

…but at a price, of course. In February of 1387, Joanna made a move that was good for her and good for Philip. Her husband Wenceslau had died in 1383, and with the rise of Philip and her sister in Flanders, Joanna did a 180 degree turn on the issue of who would succeed her in Brabant. Instead of her husband’s Luxembourg branch, she now firmly saw the future of Brabant as one in which her sister’s children would be the heirs, and so now ceded to Philip the seignorial rule of various regions and fortresses in the Overmaas, the area in southern Brabant that was under threat from William’s aspirations for Juelich. Giving these to Philip saved her from the heavy expenses that were required to garrison and maintain them. However she, and the Estates of Brabant, could remain content that the lands would remain in the family via Philip’s marriage to her sister.

The legitimacy of the terms of the Joyous Entry really depended on whether the ruler of Brabant acknowledged it as a convention. We saw in our episode on the Joyous Entry that it was almost immediately ignored, as during the war of Brabant Succession Joanna had assured her husband’s family, the powerful and imperial House of Luxembourg, that Brabant would pass to them should she provide no male heirs. So it was by no means sacred, even though Joanna recognised it. It is very unlikely that a foreign ruler after her would pay any heed to the Estates of Brabant or their constitutional conditions. This had pretty much been the case with Joanna’s husband, Wenceslau, who had conducted himself with much greater autocracy than the Estates were comfortable with. After he died in 1383 the members of the Estates of Brabant began to push for greater solidification of their own power within the political structure of Brabant. This would be much easier done with the heirs and successors of Joanna’s sister, who would be familiar with their role within Brabant. For these reasons, Joanna was able to convince the Estates to let her cede this land to Philip.

So now, Philip went into action. In early 1387, with William’s forces still obstinately entrenched in Grave, Philip got Joanna and Albert to abandon diplomatic efforts and join him in a game of stabby-Mcsword-to-the-face, and they began discussing the removal of the Duke of Guelders. Although William was a knight and warrior of great re-known and experience, once confronted with this coalition he once again sought negotiation. In late March they all began to talk, but the negotiators from Guelders kept delaying and stalling and, eventually, asked for a pause in proceedings until June. Joanna, probably completely fed up, instead raised her banners and called her forces to gather at the end of May, giving William until the middle of August to abandon his claims.

Once more, William asked for talks, but once again these collapsed. But the reason for this delaying tactic is clear. William’s plan was to utilise the greatest enmity in western Europe at the time,that between England and France, to bolster his forces. At this point, Brabant was allied to Flanders, the Duke of Flanders was a French Prince and was in control of France as its regent, and the English hated the French. So English forces joined Guelderian forces and William went on the offensive. His men lay waste to the Maasland and began to threaten the fortresses that Philip had taken over from Joanna.

Philip, in response, moved troops into his newly acquisitioned domains in Overmaas and the other allied forces went about trying to push the Guelderians from Brabant. They had some successes, including a raid on Roermond in the south, and also in battles on Brabant’s northern frontier. Again Grave was laid to siege. Once more talks were opened, and a truce was concluded that would last into the middle of 1388. In the weeks leading up to the end-date of the truce, Joanna began building up her intimidating and impressive allied forces, until William finally offered to abandon Grave. This was accepted, but when William was told he was going to have to pay for this whole folly, things once again turned sour. The Duke of Guelders hung on to Grave. Just for a moment, and as is the case of every town ever to be occupied and/or put to siege, let’s spare a thought for the poor people living there, who had nothing to do with any of this, probably weren’t even sure what William was fighting for – which was simply to be able to inherit certain areas in his father’s County of Juelich – and who all had to deal with literally years of being occupied by Guelderian and English troops, who ate their food and took up their taverns and probably didn’t pay for all that much.

Disaster at Ravenstein

A stalemate of broken treaties and uncertainty continued in the Brabant and Guelders war. William left a small English contingent to defend Grave and moved the large majority of his troops and knights to Nijmegen, creating a defensive line behind him as he went. Even though the Brabantine forces were large, they could not surround Grave unless they took the other side of the Meuse river, and thus morale dropped amongst the besieging forces as the town withstood everything thrown against it. They tried to build a bridge, but the Guelderian forces came out and destroyed it. Instead it was decided that they would cross the river downstream, at Ravenstein. William knew they were going to cross, but was not sure exactly where. He cunningly split his army in three, sending one force slightly up-river from Grave, to a place called Cuyk, and another one slightly downriver towards Ravenstein. He kept the third positioned in between them, to assist whichever force was confronted with the invading Brabantine forces. When those forces reached Ravenstein, they overcame William’s small defensive unit holding the bridge there, but then set about sacking the town, showing a tactical lack of discipline. The people of Ravenstein fled towards Nijmegen and this, along with smoke seen rising from it in the distance, told William where to send his men to face them.

The Brabant army, busy sacking Ravenstein, panicked when Williams forces descended upon them, and the venture became ought but a forlorn hope.

Two hours into the encounter on the north bank of the Meuse, and most of their troops had either drowned in the river while trying to flee, been cut down, or were taken prisoner. It was a devastating loss for Joanna, and suddenly William was very much on the front foot in this war. Now it was Joanna who sought peace terms.

French resolution

A month long truce was agreed to, and in this time Joanna set about once again trying to pre-empt the demands that would come with its conclusion. She released the towns of Brabant from their military service for three months, in return for enough money to hire 1600 troops from Flanders and France. Unfortunately for her, William had also been planning for the end of the truce, and before Joanna’s supplementary forces could arrive he launched an invasion of Brabant. For three days his troops pillaged the area around ‘s Hertogenbosch.

By seeking English support, however, William had defied the king of France, who had recently come of age and was now ruling in his own right. Charles VI, although young, was beginning to push back against the dominance of his now former regent and uncle, Philip the Bold. Despite this, he too decided that enough was enough, and that this Guelders tom-foolery with the English must end. In September, 1388, he led a large host towards the Duchy of Juelich.

The Duke of Juelich, William’s father, who had supported his son, quickly submitted to Charles’ display of force. This done, the royal army, together with the allied Brabantine forces, continued on towards Guelders, to put an end to the whole thing once and for all. William refused to meet such a large force in battle, and his father was deployed to go and talk some sense into him, which he finally did. William served up platitudes of apology and denial to the King of France, and agreed to abide by his decision in resolving the whole matter. In October, 1390, a peace treaty was finally agreed to and signed.

The threat to Brabant from Guelders was over, for a few years at least, and it was largely thanks to the involvement of Philip the Bold, and the French connection that he brought with him.

The fate of Brabant sealed

Philip had brought Brabant almost completely into his debt. By the end of the war Brabant owed Philip 15,000 gold coin écus, a fortune. Other debts accrued by Joanna, by rich lords in Brabant, were also crippling her, and so she allowed Philip to buy these out as well. Steadily his grasp on Brabant tightened and tightened.

In the same year that the war ended, 1390, Joanna and Philip met in Tournai and secretly agreed to formalise the succession of Brabant. This took negotiation with the Estates of Brabant, who were invested in maintaining a perceived inviolability of the already very much violated Joyous Entry. At the end of these talks it was official. Brabant would pass to Margaret, and not to the Luxembourg clan. To placate the Estates, of course, it would not pass directly to Philip, or to the next in line Duke of Burgundy, but to another of their children. However, it carried with it the understanding that Philip would be Brabant’s governor. Joanna herself apparently said that, only by Philip, could…

‘Our land…be held in peace and calm against any other party, better than by any other prince, lord or lady’

Joanna would rule for another 14 years, and her troubles with Guelders would continue, including another war in the latter half of the 1390s. But the point is that one of the great plays of Burgundianisation had taken place. From this point, Philip and his burgeoning Burgundian dynasty not only controlled Flanders, but also the futures of Holland, Zeeland, Hainault, and now Brabant too.

It is not clear if there was a certain point that Philip fully invested himself in the fate of the Low Countries over his native France. He had been France’s regent, until Charles VI reached his majority in 1388. When this happened Philip was brought down a rung or two on the ladder of power at the French court, so it could have been around then. But this relegation lasted only four years. Charles VI ended up expressing one of those random afflictions that monarchs can be prone to: insanity. In 1392 Philip once again came in to the ruling council, and there he would remain. But although he would spend most of the rest of his life in Paris, he had set up his low country domains to advance with a continued autonomy from the power of France, with a flavour that was particularly of his own making. Burgundian. Essentially, it is pretty clear that Philip saw his family’s future glow brighter in the prosperity and vitality of Flanders and their future low-country domains, than in the potential that lay in taking personal rule over France and bringing Flanders into the French realm once and for all. Indeed, Philip could well have taken complete control of France. Instead, he just ransacked its treasury and paid to take control of the Low Countries.

In Flanders he sought to counter the imbalance between the cities and the countryside, by establishing a new court of appeals, in which people in areas outside the cities’ bounds could seek the count’s justice, rather than going through the magistracies of Ghent, Bruges or Ypres who, quite frankly, likely didn’t care much for them or their complaints. In 1390 Philip also appointed a governor to oversee this, which gave a comital presence to the wider landscape of Flemish justice that was stronger than it had been.

Through smart diplomacy, (a,.k.a. giving lavish gifts to people) he laid the groundwork in 1396 for a truce to be called in the Hundred Years War, which in itself would allow for the eventual creation of an Anglo-Flemish trade agreement some 11 years later. This took away power from the pro-English factions in Flanders who had been the agitants in all the rebellions that the county had seen in the previous century. Most of that chaos had generally stemmed from people trying to protect their access to wool. Although there would be other rebellions in the centuries to follow, this sapping of judicial power from the cities, alongside his other centralisation methods, fortified the dukes of Burgundy against such uprisings.

Philip dealt with potential major social crises in a pretty progressive way. The Great Schism of the Church that started in the 1370s, in which a Pope and clerical headquarters were set up in France to contend with that in the Vatican, threatened to divide the Low Countries. It was truly divisive because, as we know, everybody was super smitten with the supremacy of the Church. Such simmering unrest could boil over into something way worse. In the Peace of Tournai in 1385, that ended the Ghent War, Philip, naturally a pro-Avignon Frenchman, nonetheless granted towns in Flanders the right to choose for themselves which side they took in the Great Schism. This was pretty progressive stuff, especially considering that the big cities went with the opposite, pro-Roman position that the English crown took. Rather than forcing his point of view by the persecution of proclaimed heresy, Philip instead countered the opposite view with a shrewd propaganda offensive in which he employed theologians and lecturers to make their way through his territories and speak in favour of Avignon. By 1393 every part of Flanders except Ghent, intransigently rebellious Ghent, was with Philip in supporting the Avignon papacy.

All these early actions by Philip were not instantly noticeable. It is only in hindsight that many of the moves he made become evident as masterstrokes in establishing himself and his family-name at the forefront of European politics. He became a reliable patron of the arts, granting commissions to Flemish artists to create paintings, sculptures and much more. The construction of what would be his elaborate and magnificent tomb was one such example of how he made it clear that his court would support cultural advancements, all of which would begin to seep into the fabric of Flanders and the Low Countries. Again turning to Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier:

‘These commissions began the great association of the dukes with the most talented artists of northern Europe, an association that lasted beyond the end of the dynasty.’

So then, centralised rule, diplomacy, gift-giving, creating a sense of culture and putting value in arts became the main hallmarks of Philip’s reign. With his expansionism he played such a long game that he only survived to witness its very first phase. In 1396 Joanna ceded Limburg to him for good, which was nice, but he was able to enjoy it for only 8 years.

The death and funeral of Philip the Bold

In April 1404 Philip the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy, Flanders, Artois and Limburg, died at a tavern in Halle, in the county of Hainault. His sons John and Anton were both with him. At his passing he held no less than 15 titles, and was the undisputed Lord of the Lowlands.

Philip’s funeral exhibited the same level of pomp, splendour and ceremony as befitted a man who had so masterfully used pomp, splendour and ceremony to forge for himself a position as arguably western Europe’s most powerful prince. It was a grand affair, that would involve a dignified and lengthy procession escorting his embalmed corpse from Halle, in Hainault to the magnificent tomb that he had already had built in Dijon, in Burgundy. Perhaps this was his way of saying don’t be fooled by the rocks that i got, I’m still Philip from Dijon. The immediate expenses alone necessitated that 6,000 gold crowns worth of some of his plateware and jewellery be sold. His body was clothed in the habit of a monk, wrapped in the finest wax cloth and three cowhides, before being placed in a leaden coffin that weighed over 300 kg, or 700 lb. This was placed in a carriage that was pulled by six horses, and which 60 black-robed and hooded mourners trailed behind solemnly. A massive cloth-of-gold, with black trim and a great velvet cross down its centre adorned the hearse that carried the coffin and from which the Duke’s coat of arms was on full display. The finest cloth from Bruges had been sent to all twelve of the churches that his body would stop at, on the nearly 500 km journey the Burgundian capital that would take weeks. Philip’s sons, various other nobles and members of his household retinue attended it, and high ranking clergy and nobility would come out to greet it as it entered each new city or town. From the moment it set out from Halle there would have been no person of any class, occupation or level of education, anywhere, who could mistake the dignity and esteem in which the body inside was held.

The tomb of Philip the Bold in Dijon.

The tomb of Philip the Bold in Dijon.© Wikipedia

Team Burgundy

Behind him he left Margaret, the Duchess of Flanders, Artois and Rethel. However Margaret would also die a year later, and now their children would inherit the whole lot. Surprisingly, in a very non-frankish manner, the three brothers acted amicably together upon their father’s death, and did not squabble over it all in the fashion that so many in a similar situation before them had. There seems to have been quite a team spirit about them.

John, who was already the count of Nevers, now became the Duke of Burgundy as well, and from his mother inherited other titles that came attached to the rule of Flanders, such as Artois, Franche-Comté and Mechelen. Because of his parent’s astuteness over 5 decades of European politicking, John would rule this pretty big domain, and also sit on the regent’s council of France as the most powerful member.

Anton, the second son, would be the benefactor of Philip and Margaret’s work in Brabant and Limburg. But, again, the brothers were all on the same page. For instance, a part of the family’s jewellery was to be sold, and all of them agreed that the first 25,000 crowns of the proceeds would go straight to paying off Brabantine debt. Anton was not even the Duke of Brabant yet, but the brothers understood that they only stood to gain because securing Brabant was better for the overall cause of Team Burgundy.

In Brabant, by 1404 Joanna was also going senile, and the month after Philip’s demise she signed her title over to her now widowed sister, Margaret who, ten days later, passed the inheritance onto her second son Anton. He would rule as the Duke of Limburg, the Margrave of Antwerp and the Governor of Brabant until Joanna’s eventual death in 1406, at which point he also became the new Duke of Brabant. This was the deal that had been brokered between Philip, Joanna, Margaret and the Estates of Brabant. It is a deal that further displays the genius of Philip and Margaret’s long term planning. Philip the Bold had learned his style of rule growing up in the French court, observing his pretty wise older brother, and then spent decades working with and learning from his also very able father-in-law, Louis of Male. Both John and Anton and, I suppose, their younger brother Philip had, in turn, grown up watching and learning from him and from Margaret, whose territories they were now inheriting. Anton, despite being obliged by the terms of the Joyous Entry upon taking rule as the new Duke of Brabant, brought his father’s style of rule to his ducal court, and would set in motion similar administrative and judicial structures that would begin to align the rule of Brabant with his brother’s rule of Flanders. With Philip’s political accomplishments and subtle expansionism, and then passing these on to his sons, Burgundianisation had well and truly taken root in the Low Countries.

The younger brother, Philip, got pretty much bugger-all, comparatively speaking. John, who inherited most of it, gave his title for Nevers to Philip, pretty much exactly as he would give an old toy to a younger sibling upon getting a new and better one, and Philip also got Rethel from his mother.

The start of an age

The sun was now rising on the Burgundian Netherlands.

We’ve seen how for centuries these noble families were fighting, feuding and marrying each other in a constant struggle for supremacy. Now, we’ve finally seen it accomplished so well that the term ‘Burgundian’ or, in Dutch, Bourgondiërs, would enter and, still to this day, carry cultural weight in the Netherlands today.

If something is Bourgondish in Dutch, it is opulent, lavish and extravagant. It is the pomp, splendour and ceremony which became the hallmark of political style for which the Dukes of Burgundy would become renowned. That began with Philip the Bold.

How the rest of the lowlanders would deal with the encroachment of the Burgundians, and how John the Fearless and his son would maintain momentum for it, is something we are going to get into in the episodes to come.

Sources

- A History of the Low Countries by Paul Arblaster

- The Promised Lands by Wim Blockmans and Walter Prevenier

- Magnanimous Dukes and Rising States: The Unification of the Burgundian Netherlands, 1380-1480 by Robert Stein

- Warfare in Medieval Brabant, 1356-1406 By Sergio Boffa

- John the Fearless: The Growth of Burgundian Power, Volume 2 By Richard Vaughan