To Simply Be: The Architecture of Marie-José Van Hee

Over a career lasting almost fifty years, the Flemish architect Marie-José Van Hee has developed a personal style at the heart of which is the search for harmony, simplicity and a protective effect. The Antwerp International Arts Centre De Singel in Antwerp is currently holding an exhibition about Van Hee that is as austere as her work.

The architecture exhibition at De Singel is singularly unimpressive at first glance. What you expect is a room full of models, sketches and videos of an architect proclaiming a truth. What you get is something completely different: an austere, secure, homey space, with a gallery through which visitors can quietly stroll. Now and then it is possible to simply stand still and read one of the personal letters or look at the special objects on display.

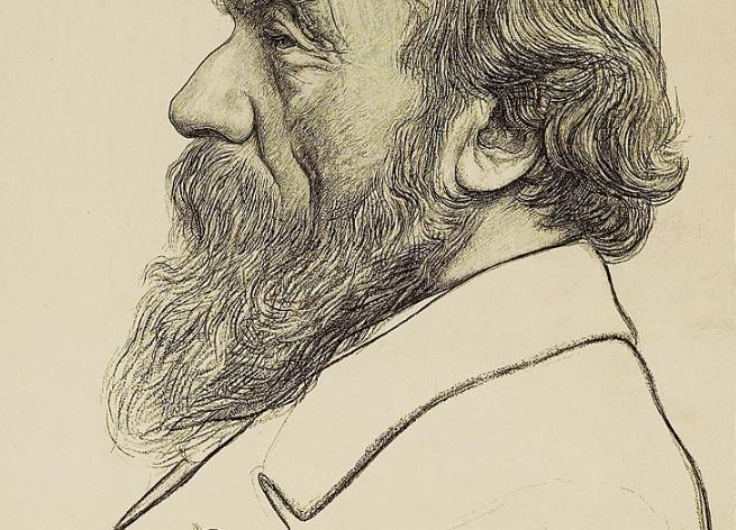

Marie-José Van Hee

Marie-José Van Hee© Jef Jacobs

Unlike so many other ‘starchitects’, Van Hee does not shout about her genius or grandeur. On the contrary, she sets the stage for the other people in her life. Anyone who knows her body of work, even slightly, will not be surprised by that gesture. For Marie-José Van Hee (b. 1950), architecture is not about architects, but about bringing people and elements together in a light-filled, soothing and protective environment. Nature and monasteries form her frame of reference; the pace of the walker determines the rhythm of her buildings.

Mainly residential projects

Throughout her nearly 50-year career, Marie-José Van Hee has worked on more than 400 projects, 250 of which have been realized. The vast majority of her realisations are residential projects. The early designs she created for family members, such as the Van Hee-Coppens residence in Deinze (1977-1979) and the Vinken-Van Hee residence in Passendale (1985-1990) showed the formal language and principles she ultimately perfected in one of her masterpieces: her own residence in a medieval street in Ghent (Van Hee residence, Ghent, 1990-1997), which was nominated for a Mies van der Rohe Award in 1998.

Van Hee's own residence in a medieval street in Ghent was nominated for a Mies van der Rohe Award in 1998.

Van Hee's own residence in a medieval street in Ghent was nominated for a Mies van der Rohe Award in 1998.© David Grandorge, courtesy of Marie-José Van Hee architecten

Through casement windows and a walkway across the width of two facades, the house opens onto the inner garden which serves as an outdoor room. From the living room, more like a hallway, several routes are possible via different levels through the rest of the house and/or through the light-rich, green courtyard garden. The reasoned placement of the windows guarantees a careful balance between light and visibility. There is visual contact with the city, but more with the sky, and from everywhere clear sight of the greenery in the protective garden.

In search of harmony

Van Hee does not approach designing a house as a grand act of self-manifestation. Rather, it is a matter of looking carefully and listening carefully. The environment itself largely determines how a house can best be laid out, where light and air are needed, and what spaces are required for the residents to live well. It is not the idea she has in her head that determines which lines go on her sketchpad, but rather the shapes, perspectives and sightlines of the place itself. In this sense, her architecture is more an attempt to respectfully respond to what is and what has been rather than a reckless signpost to a world of tomorrow. For example, the house she built in the Dutch town of Zuidzande (2006-2011) references the typical barns in the landscape and pigeon towers that were found there. The key question Marie-José Van Hee asks herself while she develops a project remains close to the specific situation and the human subject: how can I, how can the client, live here harmoniously?

The house Van Hee built in the Dutch town of Zuidzande references the typical barns and pigeon towers that were found there.

The house Van Hee built in the Dutch town of Zuidzande references the typical barns and pigeon towers that were found there.© David Grandorge, courtesy of Marie-José Van Hee architecten

Not coincidentally, she draws inspiration from religious architecture. In particular, the Romanesque Cistercian monastery of Le Thoronet, in the Var, made a great impression on her: she spoke in an interview of the “pinnacle of balance”. The monastery also struck a chord with Le Corbusier. But unlike him, the designer of the twelfth-century abbey is unknown. And that is as it should be according to Marie-José Van Hee: the architect may disappear into silence, but the architecture must speak for itself. The balance inherent in the form must translate into the experience of the user, just as the villas of Renaissance architect Palladio did.

The generation of 1974

Van Hee is part of what has sometimes been called “the generation of 1974” in Flemish architectural criticism. In that year, in addition to Van Hee, both critic Marc Dubois and fellow architects Christian Kieckens, Paul Robbrecht and Hilde Daem graduated from the Sint-Lucas Institute in Ghent. With Robbrecht and Daem, the duo who designed the famous Concert Hall in Bruges in 2002, Van Hee has collaborated on a number of eye-catching public projects over the past decades. From 2009 to 2012, the Korenmarkt and Belfortplein, central open spaces in downtown Ghent, were redesigned.

The master plan for the works, developed by Robbrecht, Daem and Van Hee, provided not only for a sloping green park between St. Nicholas Church and the Belfry, but also for the construction of a market hall based on the medieval model. This roof-on-high-legs originally did not meet everyone’s approval, but after ten years it is impossible to imagine the city without it. Anyone who has already walked under it will be able to understand what Van Hee does in her private architecture: she transforms a bare, meaningless void into a comprehensive, spectacle-free space in which one simply feels at home as a human being.

The market hall in Ghent originally did not meet everyone's approval, but after ten years it is impossible to imagine the city without it.

The market hall in Ghent originally did not meet everyone's approval, but after ten years it is impossible to imagine the city without it.© Tim Van de Velde, courtesy of Marie-José Van Hee architecten

The nature walks she enjoys provide a frame of reference for the light and vistas she incorporates into her buildings. For example, the design of one of her best-known works, the monumental staircase in the entrance hall of the ModeNatie in Antwerp (early 2000s), evolved from the idea of the walker walking up a hill. In front of him, he sees light, behind him he can continue to see the point where he left off. Which direction he will choose at the top of the stairs, is not yet known. He’ll only discover his destination when he gets there. In the Derks-Lowie house (Ghent, 1986), Van Hee designed a similarly fabulous staircase on a smaller scale.

Respect for tradition and history

The 1974 generation is sometimes referred to as the “silent generation” in Flemish architectural history. Trained in a modernist language of form, its members show respect for tradition and history. The quips and frivolities of postmodern entertainment architecture have never driven them. Their work rarely aligns with the dominant international movements in architecture of recent decades. Consequently, their influence was initially limited mainly to their own region.

Due to their work as teachers at architecture schools and by providing internships for budding architects, their ideas have had an impact on many members of the youngest generations of Flemish architects, but it was only after winning local awards (in 1997 Robbrecht, Daem and Van Hee won the Cultural Prize of the Flemish Community for Architecture) and completing eye-catching projects such as the Bruges Concert Hall (Robbrecht and Daem), the staircase of the ModeNatie (Van Hee) or the redevelopment of the Ghent centre area (nominated for the European Architecture Prize 2013) did this generation begin to generate buzz abroad.

The monumental staircase in the entrance hall of the ModeNatie in Antwerp evolved from the idea of a walker walking up a hill.

The monumental staircase in the entrance hall of the ModeNatie in Antwerp evolved from the idea of a walker walking up a hill.© Jan Verlinde, courtesy of Marie-José Van Hee architecten

Marie-José Van Hee participated in the Venice Biennale in 2012 and 2018. In 2017, she became a Fellow at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA). In 2021, the globally available Japanese-English magazine a+u devoted an entire issue to her oeuvre. This was very fitting, because the attention to tranquillity and light, which her structures subtly portray with their variation of open and closed surfaces, shares a kinship with Japanese architecture for those who pay attention.

Bridging

Elements such as the rhythm and the interruption of light, along with the permeability of the wall between the inside and outside recur in one of Van Hees’ most recent projects. Not a residence this time, but a symbolic public space in which she once again succeeds in staging feelings of protection and security with a few sober interventions, while the connection with the surroundings is at no time compromised. The Brielpoort Bridge, a bicycle and pedestrian bridge in Deinze, East Flanders, was completed in 2021.

The Brielpoort Bridge in Deinze was the very first bridge in the oeuvre of an architect for whom ‘connection’ has always been the core of her field of interest.

The Brielpoort Bridge in Deinze was the very first bridge in the oeuvre of an architect for whom ‘connection’ has always been the core of her field of interest.© Crispijn Van Sas, courtesy of Marie-José Van Hee architecten

It was, perhaps oddly, the very first bridge in the oeuvre of an architect for whom ‘connection’ has always been the core of her field of interest. But it won’t be the last. Right now, in her hometown of Ghent, preparations are underway for the construction of the Verapaz bridge, which should help turn an old part of the harbour area, now a busy and dingy traffic zone designed for car and freight traffic, into a pleasant place to live. The idea is for this bridge to accomplish for this part of the city what Van Hee has managed to do for herself and her clients in her own designs: to arrange the space so that people feel at home and connected, and can discover that harmony and connection while walking.

The exhibition ‘Marie-José Van Hee. A Walk’ continues until 21 May at De Singel, Antwerp.