To Spitsbergen and Back: Four Centuries of Dutch Whaling

The sale of the factory ship Willem Barendsz II to Japan in 1964 marked the end of Dutch whaling, which had started in 1612. Whaling in the polar regions was hard and dangerous work, the profits variable. And what about the whale population?

Following a period of exploration in the northern seas, in search of a passage to China and Japan, the battle for coveted whale oil began in 1611. Increased industrial activity in Western Europe had created a huge demand for oils and fats, while fewer oleaginous plants were being cultivated due to high grain prices. Whale oil was a good substitute for vegetable oils and fats, so merchants in the Netherlands saw opportunities to earn good money with whaling.

The Dutch whaling industry began in 1612. Given the lack of knowledge in the Netherlands with regard to hunting and processing whales, profits from the first voyage to Spitsbergen were not great. For the second voyage, Basques were hired, because they had experience in catching Greenland whales. However, due to opposition from the English, the profits were disappointing that year too.

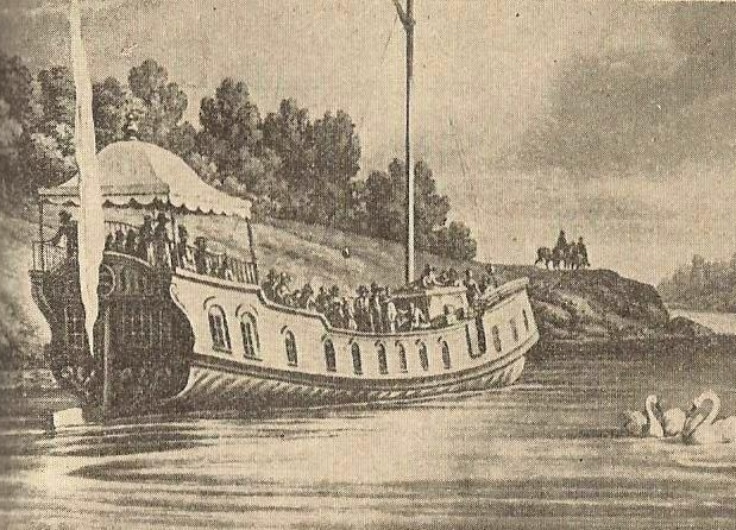

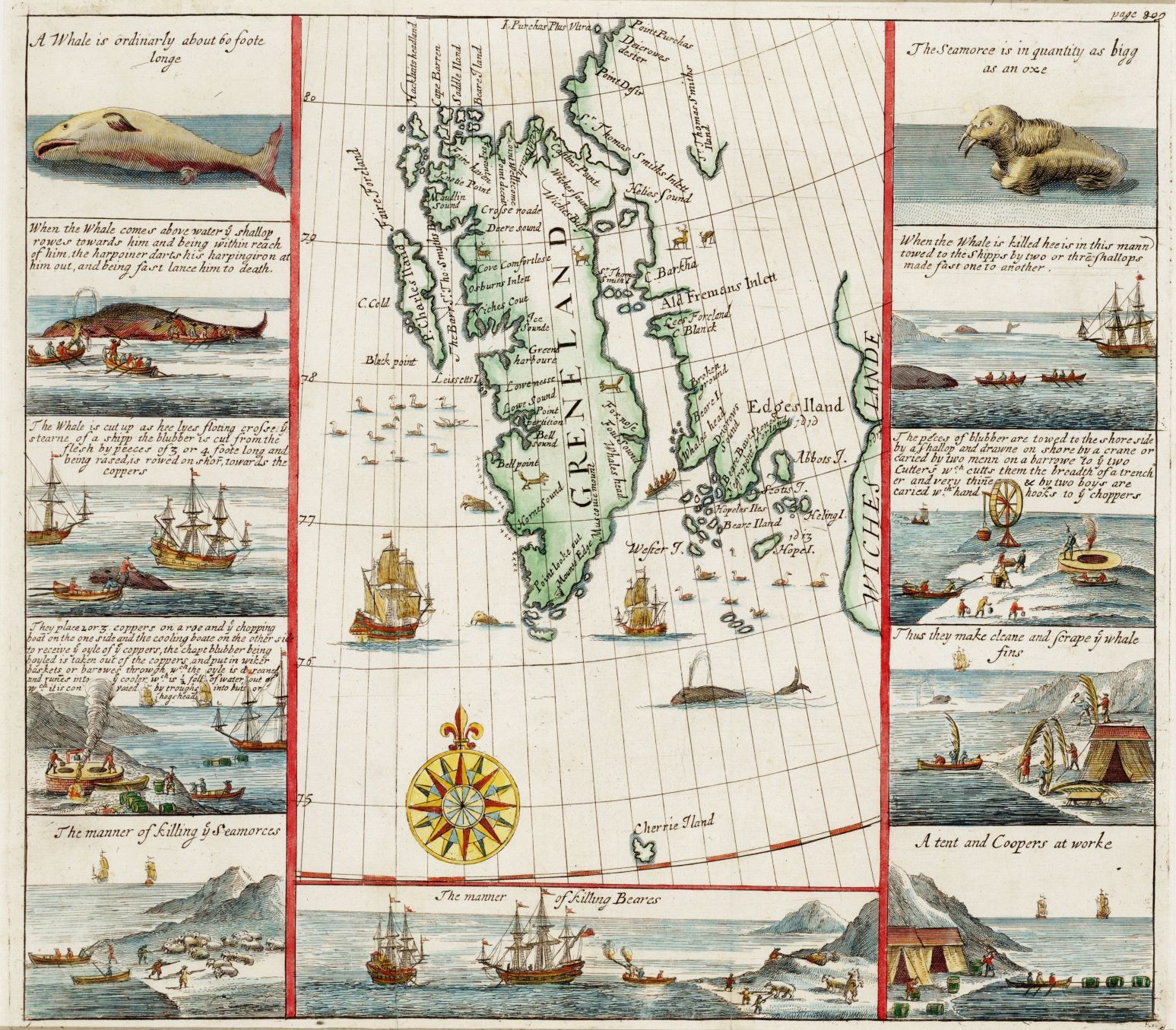

English map of the island of Spitsbergen, 1704

English map of the island of Spitsbergen, 1704© Zuiderzeemuseum, Enkhuizen

The Noordse Compagnie

It was clear, whaling had to be better organised. Merchants from Amsterdam and Delft therefore jointly applied for a patent from the States General. They got the patent for three years, on condition that merchants from other towns could join them. And so it was. Branches, or chambers, of the new Noordse Compagnie (1614-1642) were established in Hoorn, Enkhuizen and Rotterdam, and the Zeelanders joined them in 1617. From then on, the merchants formed a united front against the English and were supported by the warships of the States General.

Initially, most of the ships sailed not to Spitsbergen but to Jan Mayen Island, in the Arctic Ocean, which was discovered in 1614. There were many whales in the area and there was no competition from English whalers. In its final years, however, the Noordse Compagnie concentrated its hunting on Spitsbergen.

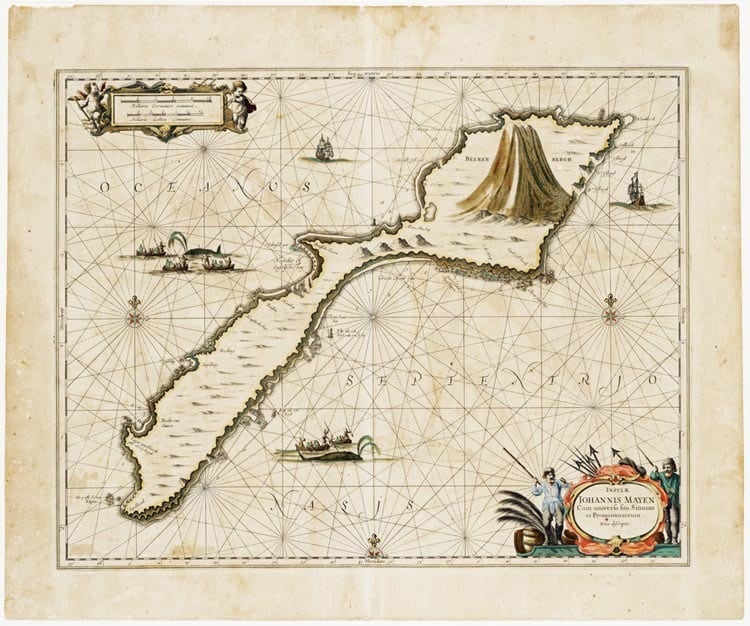

Map of the Jan Mayen Island, first half of the 17th century

Map of the Jan Mayen Island, first half of the 17th century© Zuiderzeemuseum, Enkhuizen

During this period, the English and Dutch together killed around three hundred whales annually, with about thirty ships. They processed the animals in try works along the coasts of Spitsbergen and Jan Mayen Island.

In the early years there were many conflicts on Spitsbergen, but in 1619 an agreement was reached that the English would hunt in the South and the Dutch in the North. After that the majority of the Noordse Compagnie’s oil production was concentrated in a settlement on Amsterdam Island, near Spitsbergen, jokingly referred to as Smeerenburg (Blubbertown).

Try-works on Jan Mayen Island, Cornelis de Man, 1639

Try-works on Jan Mayen Island, Cornelis de Man, 1639© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Greenland whales were dragged ashore there and flensed – i.e. stripped of their blubber – on the beach. The blubber was then boiled down in copper pans on stoves to produce oil. Every chamber had its own try works. In summer the settlement numbered about two hundred inhabitants, including a smith, a baker, several coopers, carpenters and a minister of the church. A small fortification was built on the north side for protection.

A dangerous business

With the Noordse Compagnie riven by internal disputes, its directors did not apply for an extension of the patent in 1642. From that year onwards, the hunt was open to anyone. Many of the company’s former commanders and harpooners went off to hunt whales as joint contractors, shareholders in small-scale shipping companies (partenrederijen) that took over the Dutch whaling business. This marked the start of a new phase for Dutch whaling. From then on, the number of ships grew rapidly, increasing in the space of a few years from thirty to two hundred annually, with peaks of up to three hundred.

With so many ships there, it was difficult to render the blubber in the area where the whales were caught, so the try-works on Jan Mayen and the west coast of Spitsbergen were abandoned. Instead, the whales were flensed alongside the ship or on an ice floe. The strips of blubber were cut up into smaller pieces on deck and put into barrels, to be boiled down into oil in the Netherlands, in the try-works that were set up in several of the home ports.

Flensing of a whale

Flensing of a whale© Zuiderzeemuseum, Enkhuizen

The English stopped whaling after 1650, so from then on nearly all the whaling ships came from the Netherlands – and they all had to be manned, which was quite a challenge. Initially, most of the whalers came from the countryside of North Holland, the Dutch Wadden Islands, Friesland, the area around the Lek in South Holland and the Rotterdam region, but that changed during the 18th century. There was a huge influx of seafarers from the North German Wadden Islands and at the end of the century, we see a concentration in the north of North Holland.

For all these regions the whaling industry was an important source of income. Often there was no alternative means of subsistence and poverty was rife. In most regions, evidence of a whaling culture is still manifest in whale-bone fences, scratching posts and tombstones, mandibles on prominent buildings, streets named after well-known captains, and local museums with whaling collections.

This stone in Amsterdam once adorned the facade of eighteenth-century warehouses

This stone in Amsterdam once adorned the facade of eighteenth-century warehouses© photo: Dirk Tang

The whaling industry was an uncertain and dangerous business. Big profits were offset by big losses. The price of whale oil varied widely and was not only dependent on the catch; the supply of oleaginous seeds also played a role. This made it a highly speculative business.

The final blow

In 1719, high whale oil prices and disappointing catches round Spitsbergen, possibly combined with barter trade, led Dutch shipowners to extend their whaling area to the Davis Strait, west of Greenland. In the first year, twenty-nine ships sailed to the Davis Strait, the following year sixty-four and the third year more than a hundred. However, the long and dangerous crossing and increasing opposition from Danish colonists gradually reduced the enthusiasm for fishing in the strait and, little by little, Dutch activity in the area came to an end in the last decade of the eighteenth century.

Abraham Storck, Whaling Grounds in the Arctic Ocean, 1654 - 1708

Abraham Storck, Whaling Grounds in the Arctic Ocean, 1654 - 1708© Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Round Spitsbergen, competition from the government-subsidised English whaling industry had increased again in the second half of the eighteenth century, so the profits no longer outweighed the costs, in the Netherlands. In general, it would be fair to say that the Dutch whaling industry was no longer really profitable as of 1750.

The business continued to exist because shipowners still had an interest in it via their supply companies and a year with a good catch often compensated. During the Fourth English War (1780-1784), however, the Dutch whaling industry came to a halt. The ensuing Napoleonic war and the English blockade of the Dutch ports were the final blow for the business.

And the whales?

As there was an agreement limiting whale fishing, the industry was sustainable as long as the Noordse Compagnie existed. The number of whales caught and the natural increase were in balance. However, after the patent expired, the number of whales killed annually increased from three hundred to two thousand – more than were being born. The dwindling whale population retreated to the sea ice, and many captains pursued them there, taking irresponsible risks in the process. As a result, ships were crushed by the ice and entire crews killed. The decline of the whale population is illustrated by the fact that by the end of the eighteenth century, fewer and smaller whales were being caught off Spitsbergen.

In total, around 120,000 Greenland whales were killed and processed off Spitsbergen, Jan Mayen and the Davis Strait in that period. Dutch whalers were responsible for catching 80,112 whales, 67 percent of the total catch.

Revival attempts

After the French Period (1794-1814), attempts were made to revive the Dutch whaling industry. With government support and the mediation of King William I, shipowners in Amsterdam, Wormerveer, Purmerend, Rotterdam and Harlingen were encouraged to send out ships to hunt whales. However, after a series of disappointing results, the majority gave up. Only the shipowners in Harlingen continued to send ships to the old fishing grounds to hunt whales and seals. The catch was usually disappointing, but they persevered because the employment they offered was extremely important for their region. The last two ships were taken out of service in 1852 and 1864 respectively, spelling the end for the old Dutch whaling industry.

The Whale Fountain in Harlingen

The Whale Fountain in HarlingenIn the years 1870-1872, the Rotterdam-based whaling company Nederlandsche Walvisvaart NV tried, with technological inventions, to link up with new developments in the Norwegian whaling industry. There were three voyages to Iceland, during which fin whales were hunted, but the catches were disappointing.

The final phase

Shortly after the Second World War, there was a huge shortage of oils and fats. As whale oil offered a solution, a group of entrepreneurs decided to set up a new whaling company, the Nederlandsche Maatschappij voor de Walvischvaart (NMW). With the support of various financial institutions and the government, they were able to purchase the Swedish tanker Pan Gothia and to convert it into the factory ship Willem Barendsz I (named after the man who discovered Spitsbergen, among other places).

In October 1946 the ship set off for the Antarctic Ocean, with eight whalers onboard. Once again, the majority of the crew came from the Wadden Islands and the economically weaker regions along the coast. In total, the NMW undertook eighteen voyages to the waters of the Antarctic. During the first five years, they made excellent profits, with which the loan from the Recovery Bank was repaid and a reserve of five million gulden (around 2.27 million euros) was built up.

The factory ship Willem Barendsz II, named after the man who discovered Spitsbergen.

The factory ship Willem Barendsz II, named after the man who discovered Spitsbergen.© Wikipedia

But the Willem Barendsz I was inadequate. The processing capacity was too small, and the operating costs too high. The reserve was used to have a new ship built at the Wilton Feyenoord shipyard in Schiedam. The new vessel, the Willem Barendsz II, was launched in 1955 and made nine voyages. From the very beginning, there was considerable discussion about the extent of the Dutch share of the international catch. To make the new ship profitable, 1,200 blue whales (or an equivalent number of humpback or fin whales) had to be caught. That number was never reached but, thanks to the contract of guarantee agreed with the government, the voyages did not make a loss till 1961. Once the contract ended there were three years of huge losses, after which the ship was sold to Japan, in 1964, due to the whaling quota. In 1965 the ship was bought back, converted into a fishmeal factory ship and resold to a firm in Namibia.

During these eighteen voyages, hunters from the NMW shot 27,712 whales, 4.4 percent of the total international catch in the postwar years.

Further reading? (Dutch)

Jaap R. Bruijn and Louwrens Hacquebord, Een zee van traan. Vier eeuwen Nederlandse walvisvaart 1612-1964, Walburg Pers, Zutphen, 2019, 352 pp.