On a visit to the oldest city in Belgium, Derek Blyth discovers a Roman road sign, a lost river and a hoard of antique hunters.

No sign. No explanation. The oversized dodecahedron stands on a street corner in the middle of Tongeren. The metal structure is modelled on a mysterious object from Roman times found outside the medieval city walls in 1939. No one knows what it is or where it comes from. It’s one of the world’s most baffling mysteries.

The oversized dodecahedron in the centre of Tongeren

The oversized dodecahedron in the centre of Tongeren© Philippe Clement

I first saw the dodecahedron when I visited Tongeren in the 1990s. It was the star attraction of the revamped Gallo-Roman Museum at the time. Now it seems forgotten. The world has moved on.

Tempus fugit, you might say. But some things remain the same, like the slow train from Liège to Tongeren, which is still the same old train with hard benches that stops at every little place along the way.

And yet. Go back almost two thousand years and Tongeren was the most important settlement in the region. The oldest town in Belgium, Atuatuca Tungrorum was founded in the first century BC on the great Roman road that ran from the Rhine to the North Sea. For a time, all roads in the region led to Tongeren. Even now, the road from Tongeren to Tienen follows the route of the old Romeinse Weg. It runs in a dead straight line across the landscape, just as it did almost two thousand years ago.

Roman city wall in Tongeren

Roman city wall in Tongeren© Toerisme Tongeren

The settlement at Tongeren gradually expanded into a sizeable Roman city with walls, a forum and an aqueduct – all the trappings of Roman civilisation. Compare that with Brussels, which was hardly anything more than a few huts in the Zenne marshes.

But history has not been kind to Tongeren. The city has been in decline ever since invading Franks burned the place in the third century AD. It was slowly rebuilt, but never regained its original size, so you now find stretches of the old Roman walls out in the fields, beyond the limits of the mediaeval town.

The Bishop of Cologne chose the former Roman city as the seat of Belgium’s first bishopric

Tongeren had a second stab at greatness in the fourth century (when Brussels was still just a soggy bog). The Bishop of Cologne chose the former Roman city as the seat of Belgium’s first bishopric. The first church in the Low Countries was built on the foundations of an old Roman basilica. But the first bishop, Saint Servatius, soon tired of Tongeren and moved to Maastricht in 382 AD.

And then disaster hit Tongeren again in 1677 when Louis XIV’s troops set it on fire, destroying 80 percent of its buildings. A painting in the tourist office shows the city consumed by flames. The fire marked a final blow for Tongeren, which now seems a forgotten place at the far end of the country. One slow train an hour if you are lucky.

In 1677 Louis XIV’s troops set Tongeren on fire.

In 1677 Louis XIV’s troops set Tongeren on fire.© Wikipedia

And yet. Something interesting has been happening in the past thirty years. The town has rediscovered its Roman roots. It all started in 1994 when a dusty collection of Roman relics was moved into a stunning new Gallo-Roman Museum. Sited next to the basilica, the museum was voted European Museum of the Year in 2011, the first Belgian museum to win the title.

The Gallo-Roman Museum

The Gallo-Roman Museum© Toerisme Tongeren

At the time, the entire basement of the museum was dedicated to “the secret of the dodecahedron”. Evoking one of Piranesi’s imaginary cities, the darkened interiors challenged the visitor to come up with an explanation for the bizarre twelve-sided bronze object found in more than a hundred locations across Europe. ‘We are hoping that someone will come here one day and discover the answer to the puzzle,’ a curator told me at the time.

The dodecahedron might have been part of a game, or perhaps a tool for measuring pipe sizes. Or maybe it was an elaborate candlestick holder, someone has suggested. No one knows. And, it seems, no one cares anymore, as the object is now tucked away in a glass case, more or less forgotten.

Inside the Gallo-Roman Museum

Inside the Gallo-Roman Museum© Toerisme Tongeren

Recently expanded and reorganised, the bunker-like museum now employs the latest digital technology to shed light on its collection of ancient objects. The visitor wanders around with a digital phone listening to bitesize commentaries in four languages. Along the way, video screens show interviews with the museum’s curators to add further depth.

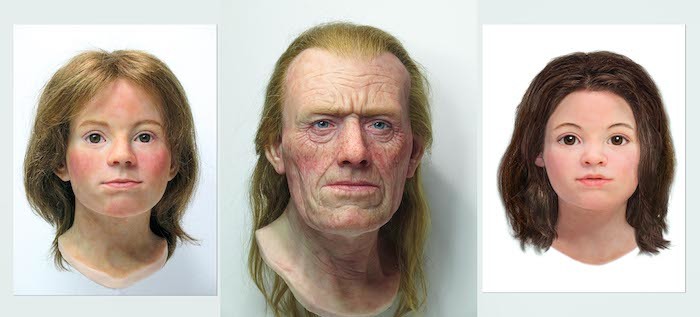

But it’s not all digital. Specialists from the Netherlands reconstructed the faces of a man and two children found in a Roman grave in Tongeren. Using DNA analysis, the researchers concluded that the man was not related to the two children, a brother and a sister. These uncannily realistic figures help to bring the past back to life.

Specialists reconstructed the faces of a man and two children found in a Roman grave in Tongeren.

Specialists reconstructed the faces of a man and two children found in a Roman grave in Tongeren.© Vlaams Erfgoed Centrum

For a time, the Gallo-Roman Museum was the main reason to visit Tongeren. But recently, archaeologists have dug down under the floor of the Gothic church to reveal astonishing Roman remains, including the foundations of a Roman basilica, a bath house and traces of two Roman homes.

The excavations have turned up a total of 45,000 pottery shards, 75,000 fragments of wall paintings and 67 boxes of animal bones. A new museum known as Teseum displays a fascinating selection of the finds.

Expertly designed by a team of archaeologists, designers, musicians and IT engineers, the museum offers a headphone-guided route through the dark underground spaces. The commentary draws attention to odd details, like a well where a Roman citizen once tossed a gold coin, a Roman stone carved by a local woman to protect her loved ones and fragments of wall paintings. The ominous background music adds another layer of mystery to the experience.

The tour ends dramatically inside the foundations of a demolished Roman villa where you see the remains of a wooden beam that went up in flames during the destruction of Tongeren in 275 AD. With the background sound of the burning town in your headphones, the cracked brick walls and blackened wood bring you close to the moment the Roman Empire died.

Archeological site in Teseum

Archeological site in Teseum© Toerisme Tongeren

Turn left for Cologne?

The town has also created an inspiring series of three walks that take you around the historical sites (along with a fun walk aimed at kids). Known as the Mijlpaalroute, the Milestone Trail, the routes are marked out with a round metal disk set in the pavement, each with the letter M in one of three colours.

the Milestone Trail

the Milestone Trail© Toerisme Tongeren

The Mijlpaalroute gets its name from an octagonal Roman milestone itinerary from the second century AD that once provided travellers with directions to important Roman towns. The stone is damaged, so some towns have disappeared. But you can clearly read the Roman names for towns like Bingen, Bonn and Soissons.

Discovered in Tongeren in the nineteenth century, the milestone itinerary is now on show in the Cinquantenaire Museum in Brussels, while a replica stands in Tongeren. And yes, you might have guessed. Tongeren wants the milestone itinerary back. The city argues that it was lent to the Brussels museum, but should now be returned, mainly because there is now a splendid museum to display it.

‘Out of the question,’ said the director of the Cinquantenaire Museum in 1999. While he allowed the rare milestone to be returned for a temporary exhibition to mark the Millennium, he refused to hand it over for good, on the grounds that ‘every little museum in the country would want something back’.

The red Mijlpaalroute is the one to follow to reach the Roman walls on the edge of town. On the way down the main street, you pass the mysterious replica dodecahedron and the Roman milestone (copy of).

Roman temple site

Roman temple site© Toerisme Tongeren

And then, the biggest surprise of all. The foundations of a huge temple were found buried under an orchard in 1964. One of the largest in northern Europe, the temple originally stood and still stands on a hill, visible from far away. The site lay forgotten for many years until recently, when Tongeren’s Mayor, Patrick Dewael, decided to build an evocation of the lower part of this impressive building, along with the base of every column. Hidden among houses, it still isn’t too easy to find. But the sheer size is proof of Tongeren’s importance.

From here, the red route takes you out to the Roman wall built of rough flint. Originally more than four kilometres long, it still runs along the edge of town, high above the fields, skirting a school and some private gardens.

The trail leads you out into the gentle Limburg countryside where a Roman spring is named after the historian Pliny. The reddish water that gurgles out of the ground was described by Pliny the Elder in his encyclopaedic Natural History as ‘an excellent remedy for kidney stones and the three-day fever’.

Roman city wall

Roman city wall© Toerisme Tongeren

The gentle art of recycling

The 1677 fire destroyed most of the city, but Tongeren’s Gothic church survived, along with a remarkable collection of religious art. The collection now forms part of the Teseum museum. Here you see ancient treasures that were hidden for centuries, including elaborate reliquaries containing fragments of saints’ bones, rolled-up paper certificates (guaranteeing the bones are genuine) and small stones gathered from the Holy Land.

The Teseum treasury

The Teseum treasury© Toerisme Tongeren

The collection includes a beautiful Virgin carved from walnut by a Maastricht sculptor. With her long, wavy hair, she seems very modern, someone who had just come from the hairdresser’s.

Our Lady of Tongeren

Our Lady of Tongeren© Toerisme Tongeren

Most of the old buildings went up in flames, but the Begijnhof (beguinage) survived the fire. The women residents somehow managed to persuade the French troops to spare their houses. Like other Flemish beguinages, it’s a quiet quarter of cobbled lanes, neat stone houses with hidden front gardens and cats sleeping on doorsteps.

The rest of Tongeren is a muddle of styles. You find a few classically styled buildings, a couple of Art Nouveau houses and a range of Art Deco buildings. It seems nothing is sacred in this town where they have been recycling building material for almost two thousand years – the Roman basilica was converted into a Gothic church; the city walls plundered to build houses; ancient columns ground to dust to build new structures.

It’s no surprise then to find the tourist office located inside a little baroque chapel, the old hospital turned into a shopping centre and a branch of Hema squeezed inside one of the only houses to survive the fire. It might seem curious to find cheap underwear on sale in a sixteenth-century half-timbered house with a beautiful round timber staircase. But, as Pliny once put it, no one is wise all the time.

The statue of Ambiorix on the main square of Tongeren

The statue of Ambiorix on the main square of Tongeren© Toerisme Tongeren

The main square has a row of lively café terraces overlooking a nineteenth-century statue of Ambiorix. Famed as the leader of a local uprising against the Romans, Ambiorix is represented as a tough Gaul warrior standing on top of a prehistoric dolmen. Not unexpectedly, children often think it’s Astérix.

Ambiorix

Ambiorix© Toerisme Tongeren

Two thousand years on, Tongeren still clings to its Roman identity, with streets called Caesarlaan and Legioenenlaan. The main civic centre – normally it would be called the Gemeentehuis – is known here as the Praetorium.

Even the hotels have chosen names that play on Tongeren’s Roman roots. The Hotel Ambiotel takes its name from Ambiorix, while the Eburon Hotel is named after the Eburones tribe, who were led into battle by the guy who looks like Astérix.

The hotel where I spent the night – the beautiful Boutique Hotel Caelus VII – is named after the Roman god of the sky (plus the hotel’s street number seven). It occupies an old house in the heart of Tongeren with a creaky spiral staircase leading to the upper floors. The rooms are decorated with antique desks, mirrors and vintage photos to add to the charm. I stayed in room 8, a snug attic hideaway with a perfect view of the caelum through the skylight window.

Tongeren’s Roman past has also inspired several contemporary artworks dotted around the town, including a strange series of three mock tumuli constructed in 2017 near the Pliny spring. Known as Third Paradise, the work is by two local artists who call themselves Le Prince-Evêque. Borrowing a concept developed by the Italian conceptual artist Michelangelo Pistoletto, they have modelled the small hills on Roman burial mounds found in the region.

Three mock tumuli, known as Third Paradise, by artists Le Prince-Evêque

Three mock tumuli, known as Third Paradise, by artists Le Prince-Evêque© Toerisme Tongeren

In late 2019, the city completed an ambitious two-year project on a site next to the Begijnhof called De Motten. It involved uncovering a one-kilometre stretch of the River Jeker (filled in the 1950s) and creating a new water park. ‘The Tongenaren always like to grumble,’ said Mayor Patrick Dewael at the opening ceremony, ‘But at least here they all agree on one thing: downtown Tongeren has become terriebel sjoon (incredibly beautiful)’.

City park De Motten

City park De Motten© Toerisme Tongeren

Every Sunday morning, Tongeren comes to life as Europe’s largest antique market sprawls across the city. Launched in 1976 by seven local antique dealers, the market now involves 350 stands spread along the old mediaeval walls and down the narrow streets.

‘You can find anything you want here if you look long enough,’ a French friend told me. ‘It doesn’t matter what. It might be a Louis XV desk or a stuffed horse. You will find it in Tongeren.’

I think she might be right. I spotted a collection of tin toys, two angels that must have come from a church, a row of German military helmets and a suitcase stuffed full of dolls. I didn’t see any horses. But maybe I didn’t look long enough.

Even if antiques are not your thing, it’s fascinating to wander around the streets. The town is always packed on the day with tourists and professional buyers. People drive here from Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Germany. Some even come all the way from England.

Once you have found the perfect antique to take home, there are several cafes where you can go for a local beer, like the friendly Café ’t Poorthuis next to the only surviving city gate. It has a warm, rustic look inside with rough stone walls, old wooden tables and framed portrait photographs.

Thanks to the antique market, Tongeren is back on the map. Once again, at least for one day, all roads lead to Tongeren.

This article was realised with the support of the Flemish Government.