Torn Between Conflicting Interests, Museums Are Looking for a New Role

Today, museums are being confronted with a number of challenging societal, historical and ethical questions. They find themselves caught in an area of tension between diverse and often conflicting interests. Many museums keep stubbornly looking for a brand-new role. Is there a way out?

Museums usually make the headlines – which is, in fact, how they prefer it – with high-profile refurbishments, announcements concerning important (and frequently extremely pricey) acquisitions, spectacular (re)discoveries and attributions to famous masters, news reports about successful exhibitions that turn out to be genuine crowd pullers, statistics that indicate that (art) museums are once again becoming popular leisure destinations, and so on. Once in a while – and fortunately not too often –, this accumulation of good news is interrupted by less positive reports: budget overruns, construction delays at one of the many museum building sites, a director who is unable to keep exploitation costs under control, arguments with a district council about whether or not a bicycle underpass should be closed, a theft here and there, or fraud. And most of the time, that would be it: a few annoying, stand-alone events that could be brushed off as ‘bumps in the road’, that were usually only briefly featured in the press. Rarely would those lead to more fundamental debates about museums and their role and meaning in society.

Unexpected blows

Generally, we could say that museums – apart from repeating a few oversimplified and self-evident clichés about ‘the’ importance of the arts for society –, for a long time, have not been putting a lot of effort in legitimizing investing public means in museums and collections, and did not appear too worried about generating political, governmental and public support either. That is definitely one of the reasons why, a few years ago, former Dutch Secretary of State for Culture, Halbe Zijlstra, and, more recently in Flanders, Flemish prime minister Jan Jambon, introduced a rhetoric and a rigid austerity, which were unexpected blows to the cultural field and the museums. It turned out that we could not take culture ‘for granted’ after all, and that the traditional, oft-repeated plea for the intrinsic importance of art and museums as sanctuaries of artistic autonomy – not only from a political angle, but also in the public opinion – did not leave as big an impression as we might have hoped for. Is it not remarkable how museums are (all too) often absent from the public debate, both as active participants and as topics of discussion? It almost seems as if museums are shying away from public debate or avoiding situations that are becoming more complicated. For that reason, they tend to be overtaken by other developments without ever being part of the debate, let alone shape it.

In February 2022, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels returned "looted art" to its Jewish owners.

In February 2022, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts in Brussels returned "looted art" to its Jewish owners.© Brabosh

A striking example is a matter that has become more prominent in the news ever since the early 2000s, i.e. that of the restitution of so-called ‘Holocaust looted art’. This concerns works of art that were taken by German occupying forces from their Jewish owners during the war, and, later still, would also include all artworks that Jewish owners were forced to part with from 1933 onwards. This is an extremely delicate matter, to which, for a long time, museums reacted rather slowly and reluctantly, and – this may sound a bit harsh – actually left their dirty work to an (unsurpassed) external committee.

Concerning the equally tricky and in some respects even more complex issue of the provenance of objects belonging to non-Western cultures, museums are not exactly at the forefront when it comes to transparency and communication – in Belgium, the Africa Museum in Tervuren (near Brussels), which came about after a lot of hesitation and rather forced by opinion makers, is a perfect example. Clearly, museums are struggling with difficult debates in public, even if it concerns one of their core tasks, i.e. the provenance and integrity of collections. Obviously, these issues are discussed between curators and museum directors, in the corridors or in the more private context of seminars and symposiums. However, asking difficult questions in public themselves does not come easy to them – questions that are not only painful at times, but to which there are often no simple answers. Could it be because, for so long, history has been building their authority when it comes to determining what the (art) historical canon is? Might that be why it is so much harder for them to critically reflect (on themselves)? They gladly invite your opinion, unless you disagree (all too much).

Broad societal, historical and ethical issues

It has also become clear that this attitude is no longer tenable in our heavily altered and continuously changing society. In this context, it is quite interesting to have a look at how a number of museums have made the news over the past several years. Ever since 2016/2017, the Van Gogh Museum and the Mauritshuis in The Hague, to name but a few, have been the focus of activists who held the fact that they were linked to their sponsor Shell against them. According to campaigners, this company is so irresponsible when it comes to its treatment of the environment and its unethical way of doing business, public institutions, including museums, cannot – and should not – get involved. In any case, it is remarkable that both Dutch museums have ended their close collaborations with Shell. The issue here is not whether this is right or wrong – It is clear, however, that, willingly or not, museums are dragged into the public debate about highly topical issues. The ongoing debate about ethics and sponsorship in the United States and the United Kingdom – where cultural institutions are even more dependent on corporate sponsorship – is more heated still. It has even led to high-profile and much-discussed demonstrations. Downplaying all of this as a random act staged by a few hotheads with a small following would be oversimplifying things. This way, whether people want this or not, museums, being highly visible public institutions with significant symbolic meaning, get involved in debates that are essentially about broader societal issues. And chances are that the pressure put on museums to justify which business partners and sponsors they decide to collaborate with will increase rather than decrease.

'End The Fossil Fuel Age Now'. Protest against 'Shell' at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in June 2018

'End The Fossil Fuel Age Now'. Protest against 'Shell' at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam in June 2018© Alex Bleu

Actually, that does not just apply to their ties to certain sponsors, but also to other (business) partners. Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum experienced just that at the time of the rather controversial, clearly forced resignation of its director, Beatrix Ruf. She was initially hired because she was known for being a power broker (among other things), who was closely linked to prominent collectors and galleries across the globe. However, the press and museum board circles – although they usually do not speak out publicly about this topic – would heavily count those same strong connections – perhaps they were too strong? – against both her and the museum. In Flanders, the 2019 commotion concerning the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent (MSK) and the relations between then museum director Catherine De Zegher and the Toporowskis, a married couple of art collectors, still remains fresh in our minds. In the wake of similar cases in very different sectors, museums were now getting involved in a much wider debate about transparency and being held accountable for the use of public resources. And moreover: about being held accountable for their choice in business and content-related partners.

Replica of a bust of John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679). In 2017 this bust was removed from the foyer of the Mauritshuis in The Hague. It is now in a room in the Mauritshuis that is not accessible to the public.

Replica of a bust of John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679). In 2017 this bust was removed from the foyer of the Mauritshuis in The Hague. It is now in a room in the Mauritshuis that is not accessible to the public.© Mauritshuis, The Hague

Museums nowadays are not only held publicly accountable about their business relations with sponsors, collectors and galleries, but also about the nature of their collections and how they decide to display them. This is demonstrated by the way the Rijksmuseum, being thé museum celebrating Dutch art and history, has recently – in line with previous heated debates about this subject in the Anglo-Saxon countries – been confronted with questions about the museum’s take on the Netherlands’ colonial history and its involvement in the slave trade in the past. The Mauritshuis, on the other hand, found itself in the midst of a crisis when the discussion about the role of its namesake and builder John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen in the seventeenth-century slave trade kicked off. In Belgium, the above-mentioned AfricaMuseum has been under attack from several groups ever since it reopened because of the way the museum’s set-up deals – or chooses not to deal – with the Congo’s colonial past, and, more specifically, Leopold II’s involvement. Whichever way this is judged in the end, it has become quite clear that the museum cannot – or, at least, can no longer – afford to ignore these issues and not to take sides, which, incidentally, most museum directors seem to be aware of.

© RMCA, Tervuren, photo: Jo Van de Vijver

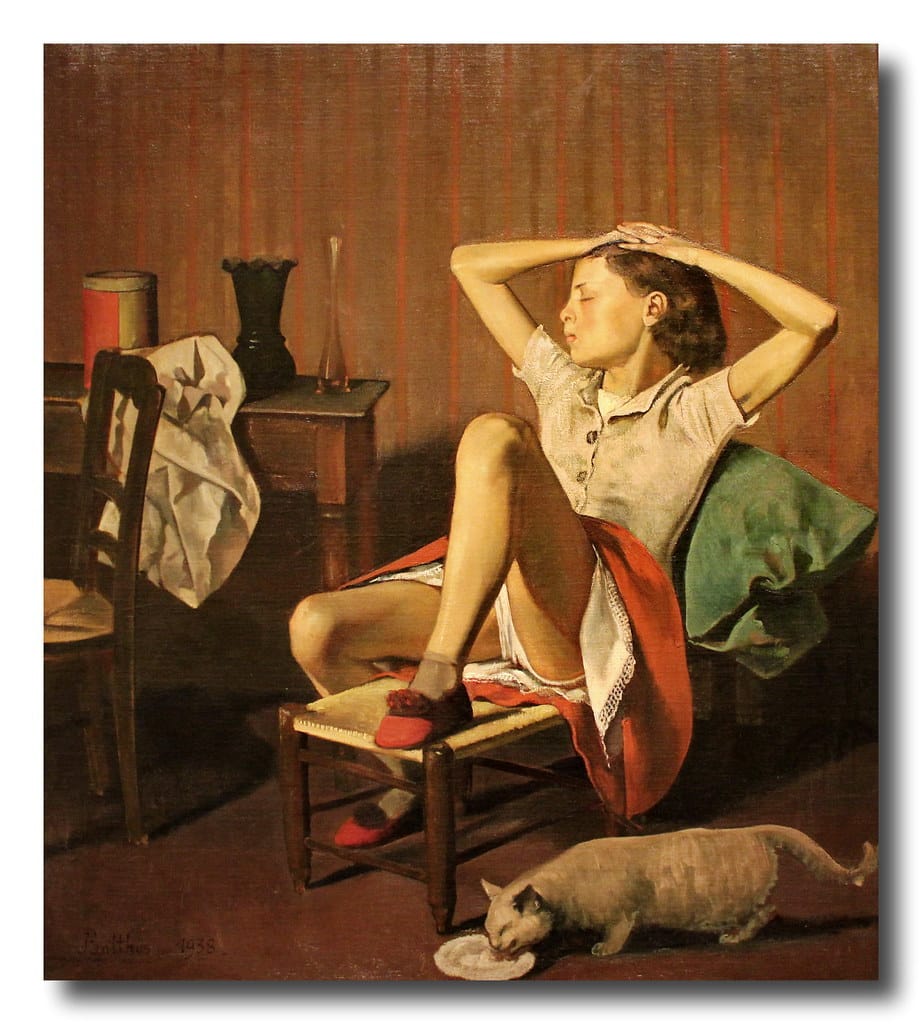

At the end of 2017, the Metropolitan Museum of Art made the headlines in a very different way, which in fact even came as a surprise to many museum insiders. In the wake of the debate concerning sexual misconduct by powerful men and the power imbalance between men and women, rekindled around the world after the Harvey Weinstein case, suddenly a petition launched on New York social media was signed by many thousands of people within the timespan of a single day. Every one of those people asked the Met to remove a painting by French painter Balthus from one of the rooms. Within a 24-hour period, the news had spread across the globe. Consternation had grown because the 1937 artwork supposedly presented a twisted, even despicable and possibly paedosexual image of budding (female) sexuality and was considered the picture of male sexual desire.

Balthus, Therese Dreaming, 1938, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Balthus, Therese Dreaming, 1938, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

We can dismiss this case yet again as a symptom of the rather unfortunate new age of prudishness, but it also demonstrates – as did previous examples – that museums and their collections have become an intrinsic part and subject of latent and rekindled public debates. I strongly believe that museums will no longer be able to avoid this in the future. This is perfectly illustrated by a quote by the new Van Gogh Museum director Emilie Gordenker, taken from a TV show entitled Buitenhof, which aired on 9 February 2020. What she said about a recently purchased pastel by Degas, featuring a monumental nude, was widely discussed in the press and on social media: ‘Museums are becoming increasingly central to society (….) The whole #MeToo debate, the debate about whether female nudes are actually appropriate for people of all cultures should be ongoing. (…) I am glad we bought it and that we are having this discussion, for this leads to a growing number of perspectives on a work of art.’ (Het Parool, 10 February 2020)

Looking back at the past

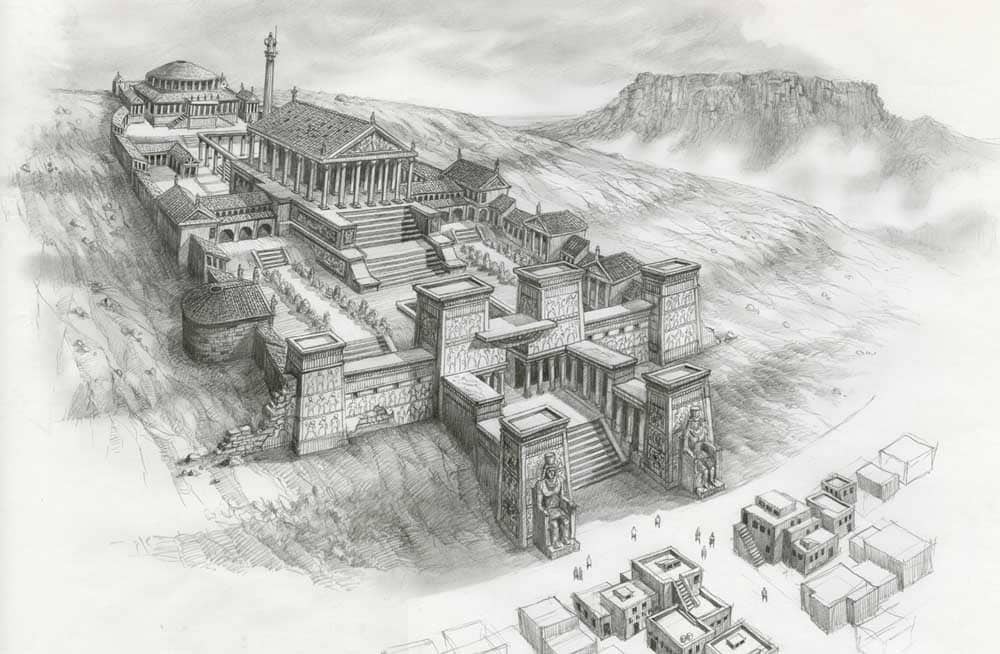

An important question to ask is whether museums – and, for convenience’s sake, I will limit myself to art and historical museums – should in fact be institutions that should – or even could – get involved in the debate about these kinds of ethical and societal issues. In this respect, it can be quite interesting to briefly look back on the history of museums; where did they come from, and how did they come to be? Where does the word ‘museum’ actually originate from? Well, it goes back to the Greek term mouseion, meaning ‘the temple dedicated to the muses’, i.e. the tutelary deities of the various arts. In the Hellenistic period – over two thousand years ago – the mouseion was a novel institution. Back then, the mouseion was a place that was open to the general public, where people could meet, a space to store special (ceremonial) objects, a place for knowledge creation and new ideas, discussions, lectures, (philosophical) debates and research, a place with a library as its beating heart, dedicated to all of the arts, and a sacred, holy place, a ‘temple for the arts’. In Athens, for example, the mouseion was where Plato’s Academy gathered and in Alexandria, the renowned library was part of the mouseion. Surprisingly, it seems these characteristics continue to be very topical and inspirational – the museum derives its name from an innovative and inspirational space, with debate and research at its core.

19th century imaginary reconstruction of the Mouseion in Alexandria

19th century imaginary reconstruction of the Mouseion in Alexandria© Researchgate

The museum as a public place of service to the whole community is a concept that has its roots in the Age of Enlightenment. One of the milestones here is the 1753 Parliamentary Act, which stated that the English Parliament accepted Sir Hans Sloane’s donation. The British Museum was actually built on this donation. The Parliament purposely returned to the ancient Greek concept of the mouseion as a storage space and a centre of research: ‘All art is interconnected (…) one general repository, not only for the inspection and entertainment of the learned and the curious, but for the general use and benefit of the public.’ What is crucial here is the ending: the mouseion is intrinsically assigned with a societal and educational task. It is a public institution belonging to and made for the general public. It is not just about investigation and research; it also concerns enjoyment and relaxation (entertainment). The museum is publicly tasked with uniting the practical and the pleasurable. During the first half of the nineteenth century, a lot of museums were founded throughout Europe. That was not only spurred on by the Enlightenment ideals and the early eighteenth-century examples – the displacement of art and religious heritage in the wake of the French Revolution and the art confiscations of the Napoleonic Wars, the desire to design ‘the’ identity of existing and new-born European nations by way of museums, a growing art (historical) consciousness and pride of the cities that had to be propagated, the ability to elevate both the audience’s and future artists’ taste levels and their understanding of quality through museums and exhibitions during the Industrial Revolution, and, afterwards, in the nineteenth century, the awareness that museums can make a valuable contribution to the appeal of a city and the revenue generated by tourism. And that is just naming a few of the most important factors.

Area of conflicting societal interests

What we also have to consider in this context is the fact that museums in this day and age are not autonomous institutions that were established solely or even predominantly because of a love for art. Ever since the end of the eighteenth century, museums have been primarily founded because of the vested interests national and municipal governments, the middle classes and the political, administrative and financial elite had in them, and more often than not these were borne out of specific ideological and societal expectations and objectives. This is not necessarily problematic, but in contemporary debates about museums, we tend to ignore all too quickly how instrumentalization at the service of interests besides artistic and art historical ones is an intrinsic part of the genesis of art museums. Museums were not founded to serve as an artistic counterforce and were not considered as such. On the contrary, museums were important symbols of the establishment. In fact, taking quite the leap, the same goes for the most part of the first half of the twentieth century. Most museums – in Europe, at least – are funded and controlled by governments. There is definitely a lot of private patronages to support existing and emerging museum initiatives, but we can hardly ever consider these to be explicit counterforces.

Museums have been primarily founded because of the vested interests national and municipal governments, the middle classes and the political, administrative and financial elite had in them

All of that changes in the post-war era, and eventually leads to a thirty-year period that turns out to be quite exceptional in the history of museums. From 1950-1955 onwards, museums that focus on contemporary art, in particular, started developing at the speed of light into high-profile places that aim to become explicit counterforces when it came to popular tastes and appreciation of art, which is, for instance, exemplified by the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven and Rotterdam’s Boijmans van Beuningen. A couple of decades after that, the Ghent SMAK, the Antwerp M HKA and the Ostend PMMK (nowadays better known as Mu.ZEE) were established in Flanders. Obviously, this development is closely linked to the fundamental societal changes that occurred in the 1950s and 1960s. For a while, it seemed that the publicly funded museum had become structurally accepted as a place that provides a home for opposing views, a space that makes room for counterforces, and is willing to do so. However, is that still the case today? Regardless of the interesting question, which we will not further discuss here, whether this period was not too highly romanticized, I believe that, ever since the 1980s, important structural and operational changes have been gradually introduced into museums, which forces them to, more than ever, work within an area of conflicting societal interests.

Many museums have been somewhat adrift for the last couple of years. They are looking for an identity, on a continued quest for a new role and meaning

So, what are those changes? Well, to name but a few, there is the art market that has been booming since the 1980s and has since exploded, demographic changes, a drastic change in the make-up, backgrounds and expectations of (potential) visitors, a profound professionalisation and commercialization, the fact that governments are kept at bay because of growing independence and privatisation, ever-increasing expectations in terms of audience reach, a decrease in public funding, considerably increased pressure when it comes to generating your own revenues, the expectation that the museum collaborates closely with the corporate world on the one hand, and private investors and collectors on the other, the fact that museums are no longer the obvious institutions dedicated to ‘high’ culture, but have become part of the wider leisure field, and rapid – at times erratic – changing trends and tastes. Because all of these developments – and despite the fact that many of them are actually intrinsically positive – many museums have been somewhat adrift for the last couple of years. They are looking for an identity, on a continued quest for a new role and meaning, and also searching for ways and partners to help them survive (financially). This process is fraught with pitfalls and takes place in a complex field of tension, which I illustrated with the above-mentioned examples. To what extent do wealthy collectors and gallery owners influence a museum’s exhibition and collection policy, how and to what degree should a museum take a political and societal debate generating a wide variety of opinions, e.g. on slavery, the colonial past and multiculturalism, into consideration, to what extent should a museum determine which sponsors and corporate partners to choose based on ethical criteria, and how should a museum react to (a certain part of) the public opinion, including mass (social) media appeals? How do museums react to changing societal perceptions in the ‘#MeToo’ debate and the discussions concerning gender (in)equality? To what degree can a museum still afford to create a critical or challenging exhibit considering the pressure exerted by, and the high expectations associated with, the number of visitors? Whichever choice a museum makes, it seems caught in a web of frequently conflicting interests and societal expectations.

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam

The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam© Pixabay

Is there a way out? Is ‘the’ museum doomed to be behind the times for eternity, and to be at the mercy of larger powers and interests that are out of its control? Is the museum by definition a place that cannot (or at least: not anymore) be an opposing force and should always play it safe and, by way of compromise, should always take as many interests as possible into account? Definitely not. Both in the Netherlands and Flanders, we can find examples of museums that are successful both when it comes to the content they bring, and in business, proving that there is indeed another way, and that a museum is able to find its way to an audience, the press, stakeholders and sponsors if it opts for quality, a clear distinct profile and a strong brand identity. However, individuality as such is not enough. In my opinion, there is no going back to the museum as an authority and as an infallible beacon of good taste, knowledge and insight. There is no question that sharing knowledge remains the museum’s core mission, but it needs to do so from a position of integrity, openness and a willingness to engage in discussions; there should be room for deliberation and debate. Museums have so much to gain by not just providing us with answers, but by also taking the risk to ask questions and by critically reflecting on themselves, their collections, their history and the way they operate. An open debate – not only do museums welcome it, but it is also actually part of their genetic make-up. The incredible, nearly 2,500-year-old mouseion concept, i.e. an open house for the arts, reflection and debate, has not lost any of its meaning and relevance, nor has it said goodbye to any of those Enlightenment ideals connected to the earliest eighteenth-century museum initiatives. Combining both is, at least in my own personal view, an important beacon and a source of inspiration for the future of museums. Moving forward by looking back.