Death is Living Culture at Funeral Museum Tot Zover

A funeral museum does not immediately appeal to the imagination. But Tot Zover (So Far) in Amsterdam knows how to surprise us with exhibitions that are informative, thought-provoking, touch a sensitive chord and make you laugh. No taboo is shunned here, and funeral cake is just as much a subject as seventeenth-century post-mortem portraits or death masks.

These days thousands of them are rolling out of the oven again: the dolls made of bread that are placed on home altars on All Souls’ Day, together with the favourite drink of the beloved deceased and a portrait. At least in Latin America, where baking and displaying bread dolls is a widespread practice. In the Netherlands, this is much less the case “except if it were up to Albert Heijn”, according to a display case text in Museum Tot Zover. Underneath it is an advertisement with which the supermarket chain tries to entice customers to purchase culinary self-help packages with a cultural-historical slant.

Rituals room at Museum Tot Zover

Rituals room at Museum Tot Zover© Tot Zover

This showcase text typifies Tot Zover. The museum has an eye for mourning rituals from different cultures and provides clear explanations, but it does not shy away from an ironic quip and a critical aside. That tone surprises many visitors. They usually arrive with low expectations – a museum about death, moreover, located on the fringes of Amsterdam – but often linger for an hour or more, which is a relatively long time for a small museum.

The lack of anticipation probably has to do with the rarity of anything with which to compare it. Not only is Tot Zover the only funeral museum in the Netherlands there is also little that resembles it internationally. The Museum für Sepulkralkultur in Kassel, Germany, is one of the few exceptions and it is no coincidence that they also work together with Tot Zover. This scarcity is in fact quite strange since this museum is about something that we really all have to deal with: death, mourning and remembering.

'Weeping Teacup' by Robert Lazzarini, 2003

'Weeping Teacup' by Robert Lazzarini, 2003© Tot Zover / Cramwinckel

The basis for Tot Zover was laid by Henk Kok, a sales agent in funeral articles and funerary historian. At the end of the 20th century, his private collection was housed in a foundation and not long after, the Amsterdam cemetery De Nieuwe Ooster made a building available to exhibit the collection in the future. In 2004, the foundation contracted museum professional Guus Sluiter, who then shaped the initially amorphous idea, and three years later the institute opened its doors.

The name on the façade with its two highly graphic T’s in the shape of crosses, also forms an eye-catching logo. The unmistakable symbol of mortality is counterbalanced by the open ending that the name suggests. Death is not a final chord here, but the beginning of the process of grieving with all the rituals of commemorating, remembering, and coming to terms, that go with it. At Tot Zover – death – and in all its aspects – is living culture.

The exhibition programme shows how versatile it can be. There are exhibitions about flowers at funerals, rituals surrounding the death of a beloved pet, the design of coffins and urns, and the role that music can play in a funeral. Every angle is approached seriously and thoroughly, nothing is taboo. So, there have also been presentations about cancer (Malignantly Beautiful) and even suicide (The Fowler). Tot Zover wants to invite a conversation about death, not as something gloomy but as an essential part of life. Or as Rainer Maria Rilke’s quote on the museum’s website puts it: “Death wounds, but at the same time lifts us up to a higher understanding of ourselves.”

'White Funeral Meal' by food designer Marije Vogelzang

'White Funeral Meal' by food designer Marije Vogelzang© Tot Zover / Peter Lange

The success of Tot Zover can largely be explained by the light touch employed in addressing its focal area of interest. A good example of this is the current exhibition Een lekkere dood (A Delicious Death), about the role of food and drink play surrounding someone’s death. There are photos of the glasses of wine being raised around the coffin for a final toast and a jar of piccalilli, a favourite food that a grandfather being laid in his grave. The now world-famous White Funeral Meal, with which food designer Marije Vogelzang graduated from the Design Academy in 1999, still wows us with its porcelain bowls in which only white food is served. Studio Lernert & Sander’s video is downright hilarious, in which the pair use sacks of flour, a pallet of eggs and a coffin as a baking tin to fabricate a giant funeral cake in a crematory.

The approach taken by these sorts of works makes it easier to get people talking about things they’d rather suppress. Tot Zover also actively appeals to visitors, by asking them, for example, about their wishes for a last supper in A Delicious Death. One writes ‘Belgian fries’ on a note, another lists a five-course dinner and a third mentions ‘Mom’s chilli’.

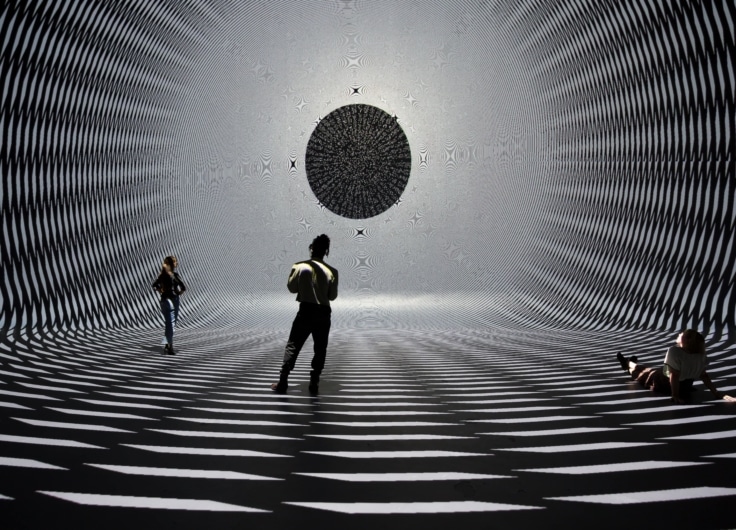

'Twilight' by Sarah Grothus

'Twilight' by Sarah Grothus© Tot Zover / Gert Jan van Rooij

Tot Zover often collaborates with contemporary artists and designers, which results in special presentations. Filmmaker Vanesa Abajo Perez, for example, made an installation in which terminally ill people learn to look at the world from a different perspective than that of their failing bodies. And Sarah Grothus transformed the museum spaces into a mysterious in-between world haunted by ghosts, skeletons, and all kinds of hybrid creatures. Although the exhibition by herman de vries was not made especially for this space, quite a few visitors who had seen the original during the Venice Biennale found the meditative installations of sticks and stones more at home here.

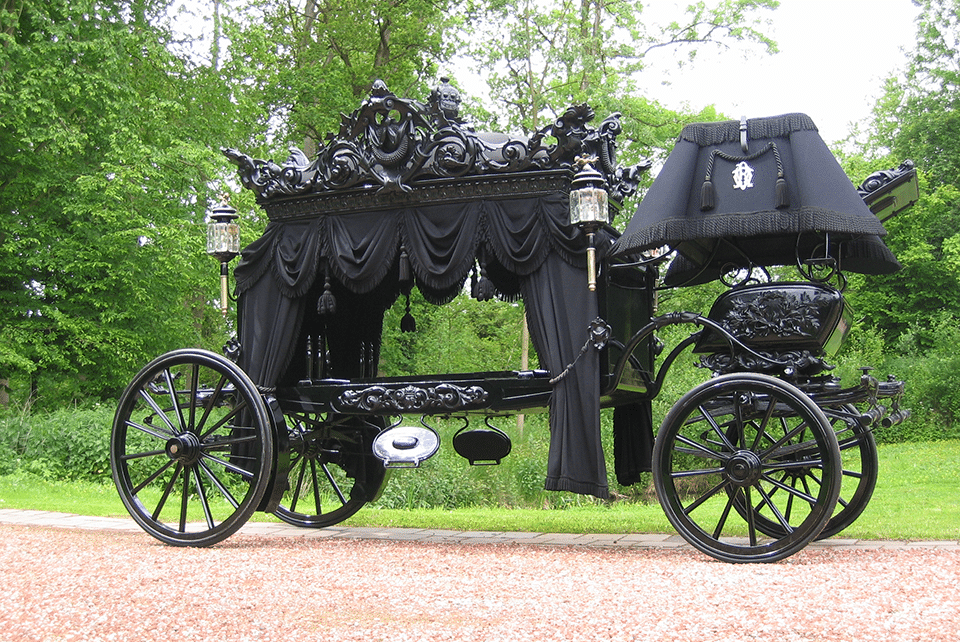

First-class hearse

First-class hearse© Tot Zover

Tot Zover has a permanent display along with its temporary exhibitions. A large part of the collection of three thousand objects can be seen here, except for the carriages, which are really too large for the modest rooms. Instead, miniatures are on display, in combination with many generations of hearses (the museum has the largest collection of these in Europe…).

Conspicuously absent are the stretchers and other paraphernalia you might expect to find in a museum largely funded by the funeral industry. The focus is very much on the perception of the clientele. And a great deal of attention is paid to the cultural differences in customs surrounding death. For example, there is a series of photo portraits of one hundred and eighty Amsterdammers – each one representing a different nationality in the city – who were interviewed about their interpretations of the end of life.

To Zover is jam-packed with information, via text panels and QR audio fragments, but the variety on offer is such that you don’t easily get bored or tired. The masterpieces of the collection have been saved for the last room, in the rear to the left.

Hair bouquet of the De Hoog family

Hair bouquet of the De Hoog family© Tot Zover / Peter Lange

Here you can see part of the considerable collection of hairpieces, a phenomenon from the Romantic mourning culture denoting medallions and small paintings made from the hair of the deceased. Tot Zover has an exceptionally large three-dimensional bouquet, in which locks are shaped into petals and the stems consist of braided strands.

Another highlight hanging in the same room, is a children’s portrait acquired in 2021 by Nicolaas Maes (1634-1693). During the process of restoration, the half-opened eyes and the pinkish blush turned out to be a later addition to make the painting more marketable. But this child was already dead at the time it was painted and the wreath of flowers around the head was a strong indication confirming the suspicion it was a post-mortem portrait.

'Portrait of a deceased girl' by Nicolaas Maes (1634-1693)

'Portrait of a deceased girl' by Nicolaas Maes (1634-1693)© Tot Zover / Peter Lange

Through its specialized work in a rare niche, Tot Zover has developed into an expert in the field of mourning culture. The knowledge gained is shared with interested parties and a platform, the Funerary Academy, has been set up to link scientists who are working on the subject from different angles. It’s almost inconceivable that the museum does all that with a staff of five and limited resources. But that doesn’t stop Tot Zover from making ambitious plans. For example, plans are being hatched for a successor to Afterlife, the large indoor and outdoor event from 2011. But before that, 39 unique dance of death figures are on display, from the sister museum in Kassel, which will soon close for renovation. Preferably in combination with a dance of death by the Nederlands Dans Theater to bring this heritage to life.