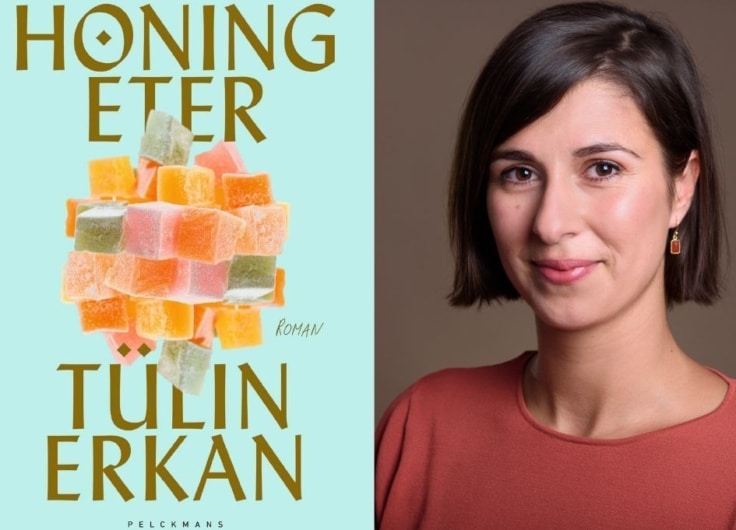

Students Translate Tülin Erkan’s Novel ‘Honingeter’

Students from two British Universities, UCL and the University of Sheffield, teamed up to translate an extract from Honingeter (Honeyeater), the debut novel of Flemish-Turkish writer Tülin Erkan. You can read the translation of this story that deals with the multilingual, with an introduction by a student.

Tülin Erkan’s debut Honingeter (2021) is a novel that crosses borders. Set in an airport terminal in Istanbul, the novel pushes through cultural differences, exploring themes which most of us also have experienced regardless of our background: the difficulty of saying goodbye, the search for belonging, the fear of forgetting and trying to find the right thing to say. In a way, Honingeter proved the perfect text for a translation project, for working together and searching for the right words.

Rebs Nelsey, student-translator: “It was an incredible experience to work with other people, a translator, and to be able to work with the author as well”

In December of 2023, this is exactly what we did. Dutch studies finalists from the University of Sheffield and UCL embarked on the challenge of translating an excerpt of Erkan’s novel, from Dutch into English. For many of us, this was our first experience with literary translation, so working with professional literary translator Jonathan Reeder and the author herself was an insightful and enriching experience.

How do you go about translating a novel?

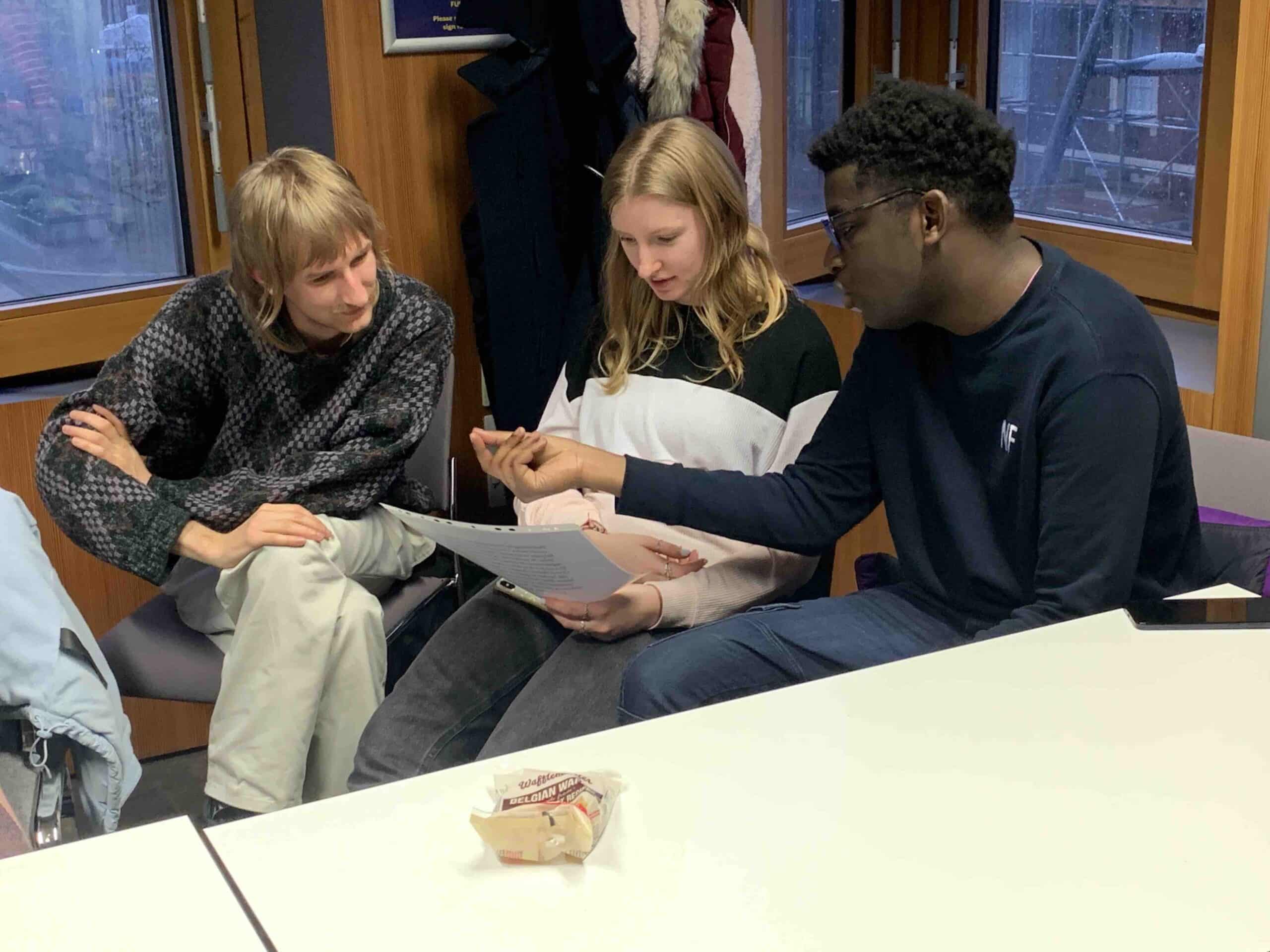

We began by each making an individual translation of a segment of the text, before coming together into small groups to create a final version between us. It sounds simple, but it was actually far from it. The members of my group, who had all learnt Dutch for the same length of time and in the same classes with the same teachers, had come up with entirely individual translations, varying in word choice, tone, length and structure. It was quite eye-opening to see how many different interpretations we had for just one bit of text. After lots of discussion, compromise and debate, each group produced their final version, ready to present to the author at our final Translation Symposium.

On the 8th of December, we all came together to discuss our translation challenges with the rest of the students, Jonathan Reeder, and Tülin Erkan. This was a highly collaborative and creative session where we were free to exchange ideas and offer solutions to challenges we had faced.

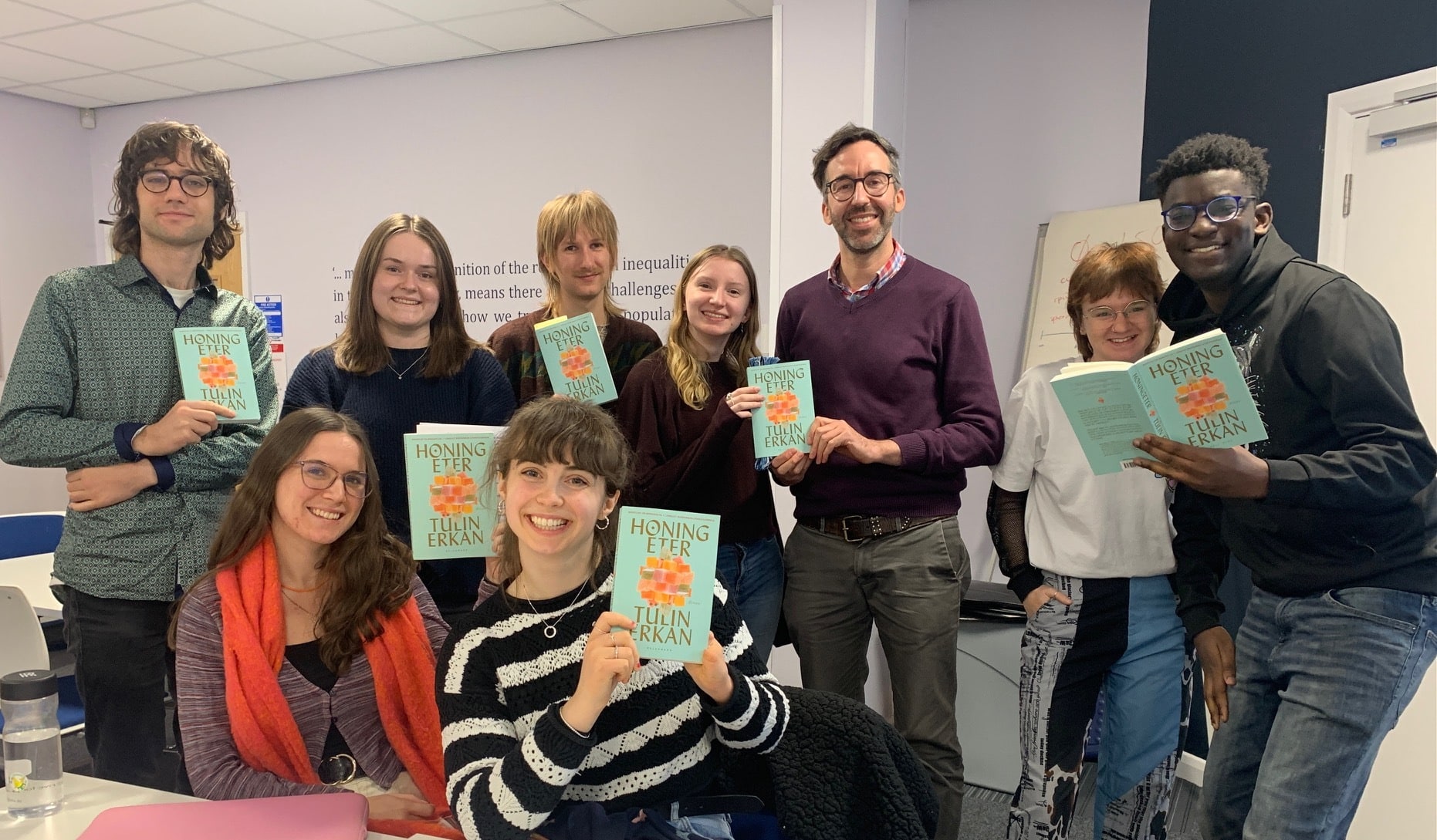

Students of the University of Sheffield and UCL at work with Tülin Erkan and Jonathan Reeder.

Students of the University of Sheffield and UCL at work with Tülin Erkan and Jonathan Reeder.Following the symposium our editorial team made the finishing touches, reviewing and implementing suggestions made by Jonathan and the group. And, after a few weeks of collaborative work, we finally had a full, complete sample translation which we could all be proud of.

Reflecting on the experience, the key for us as English-native learners of Dutch was to stick to what we knew best, the English language, all the while keeping the tone and intent of the original text. In this way, we had to make sure that the text read naturally in English and the structure and language flowed well but we also recognised the importance of keeping the poetic and cinematic tone of the original. After all our role as literary translators was not to write a new narrative but to adapt it to a new English-speaking readership.

It was nice to work with an author and text from Flanders. It definitely offered an insight into the cultural and linguistic variation between the Netherlands and the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium.

Looking back, this project really reinforced the importance of literary translation. Translating a novel into English often means it will reach an international audience. We hope that our English sample translation of Honingeter has done the original justice and reflects Tülin Erkan’s unique and cinematic storytelling.

Emma Halliburton (BA Modern Languages and Cultures, University of Sheffield)

Editors and translators: Charlotte Armett, Agatha Bos, Nathanael Fogbel, John Furness, Catriona George, Emma Halliburton, Pop Mainwaring, Rebs Nelsey, Elizabeth Speakman, Theo Taylor, Rachel Whitfield, Alice Willett, Tom Macaulay, Alexander Bogdan

Tutors: Filip De Ceuster (University of Sheffield) and Christine Sas (UCL)

Project Coordinator: Henriette Louwerse (University of Sheffield)

The Translation Project was sponsored by Nederlandse Taalunie, Flemish Foundation for Literature, and Netherlands Embassy in London

A short video report of the project.

Excerpt from 'Honeyeater', pp. 23-35

● REC

The top left of my screen offers a clearer view of her posture and facial expression. This camera is located in a well-lit corner of the airport. Billboards advertising Qatar Airways’ business class illuminate her face. ‘Fly with a smile.’ A model with a perfect row of teeth and a cocktail in hand smiles radiantly at her. I zoom in. The woman on my screen has stopped mumbling to herself and is now biting her lip intently, as if weighing up the words in her mouth. Her neck is long. She’s definitely not wearing enough layers for this time of year: a pair of dark trousers and a dark blouse, no jacket. She picks up her handbag from the floor and cradles it in her lap. Her knuckles turn snow-white on my screen. I wonder what’s in the bag, where the rest of her luggage is and why she’s clutching the bag so tightly.

I notice a little boy, around six years old, with a neat side-parting, descending the escalator alone. Not particularly suspicious, but there’s no adult in his vicinity. A child wandering around the airport on their own is never a good sign. Perhaps I should send Hasan to investigate, just to be on the safe side? It looks as though the fear of falling has been instilled in him, his little hand is gripping the handrail so tightly. He walks timidly towards the woman with the handbag. His hands are clenched into fists. The woman averts her eyes from him, even though he’s now standing right in front of her. She shakes her head subtly. She purses her lips. The boy grows more tense. Is the woman too young to be a mother?

Terminal 226

Whoever designed these supposedly ergonomic seats needs to seriously consider a career change. I try to straighten my back, vertebra by vertebra. The chill of the metal seats permeates straight to the top of my head. I try to use my handbag to keep myself warm. If you hold onto leather long enough, it becomes supple and warm, a bit like a sleeping body under a thick winter duvet.

I can’t remember the last time I slept through the night here, let alone exactly how long I’ve been here. No matter how important every second in an airport feels, the hours seem to evaporate into thin air. Here, it is neither night nor day: The lights blaze endlessly, but outside it is dusk. I know that for sure.

A little boy washes up out of nowhere at my feet. He comes too close, his hair in a neat parting, his eyes as big as roasted chestnuts.

‘Mere…’

My diaphragm contracts involuntarily. Larynx, vocal cords and lungs clog up. This has been happening a lot recently – these bloody hiccups. I hate losing control of my body. With a strained voice I try to shoo the boy away, to set boundaries, to make it clear that I can’t be what he needs. But how do you explain boundaries to a child? And that he’ll have to spend his whole life contending with them? Between countries, between bodies, in the sea, even in the sky. I once read that each country determines the height of its own airspace. So how does a person know how high to jump?

‘Mere…?’ he asks again.

French? I bite down hard on my lip. So hard the blood drains from it.

‘Merhaba.’ Panic. Neither of us can do this. While I survey my surroundings, the boy tries to keep his bottom lip from trembling. He’d expected something more from me. That I’d pull him into my lap, gently cradle him, perhaps. Or that I’d take his clammy hand in mine and set off in search of someone to look after him in my place. A mother, a big sister, a grandfather. Or even a father? This place is teeming with men who could be fathers.

A man with a buzzcut rushes towards the little boy and grabs him by the hand. He looks frantic with worry, as if he had lost the crying child forever. He shoots daggers at me. The man and the boy walk away from me as quickly as possible. It’s as though they’re ice skating across the smooth floor. This place is teeming with fathers.

My mother’s grasp. I can still taste our arrival at the tiny Nevşehir Kapadokya airport in the middle of the night, summer after summer, my mother and sister beside me. It smells of plastic, kerosene, and the endless night. As a trio – my mother in the middle, a daughter on each hand. Her hand is clammy in mine: has he forgotten us?

Summer after summer. Being patient, waiting for our bright blue suitcase to glide past, then joining the slow, snaking queues towards border control. Summer after summer. The fear that I no longer look like my passport photo, that my hair has grown too wild, that my cheeks are less chubby and childlike. And that we’ll be put on the next flight to Belgium. Summer after summer. The sigh of relief as they stamp our passports. After all the formalities, we go to find him. The airport is surrounded by a wall of men: frustrated taxi drivers, serious men, nervous men, sleepy men. All waiting, motionless. I listen carefully and hear the silence of my father, wispy clouds of cigarette smoke spiralling above his head.

My mother drops our hands and drunk with sleep we go and greet him, knowing all too well that arriving also means saying goodbye. But for now: being carried in his arms, the smell, always the smell, his chest rumbling against my ear, my arms around his neck. Then in the car: the familiar smell of the upholstery in the beat-up Volvo, the grown-up whispers from the front seat, the hypnotising evil eye hanging from the rear-view mirror, midnight blue. Knowing that this will slip away too.

● REC

When night falls, the grey fuzz on my screen fades and everything becomes sharper, more pronounced. Through the blast-proof windows: the lack of stars, the twinkling streetlights from the edge of the city, the last few aeroplanes manoeuvring on the runway, the contours of her face.

My evening shift ended an hour and a half ago. And yet I can’t help myself from staring at the screen. The tea boy just popped in to empty my ashtray and refill my teacup, leaving a few extra sugar cubes on the saucer. I dismissed Hasan, who normally works the night shift, and sent him off to terminal 218. Suspicious subject by the souvenir shop, you know, those unsavoury types that tend to hang around here. When night falls, everything goes painfully quiet. Conversation fizzles out and passengers ready themselves for sleep. Cat-like, they curl up on the benches. Experienced travellers arm themselves with ear plugs, eye masks and sleeping pills. Only the woman remains sitting. The camera zooms in on her right side. She is watching an old man on the row of seats in front of her. A fortress, or so he seems with his too-big coat. His slumped posture and his gently nodding head betray the fact that he’s asleep. At dawn he’ll take the first flight to Kayseri, deep inland: his eldest son will pick him up; they’ll plough through snow on the way to his village; and once home, they’ll light a fire in the hearth that for generations has kept out the winter cold. The logs will crackle. Or so I like to think. I often imagine whole worlds for other people. For the woman on my screen too. Who is she and why do I keep on noticing her?

Suddenly she starts to rummage frantically in her bag, with half her arm inside, searching, until, with the utmost precision, she produces a snake-like instrument. It looks like earphones, but disproportionately large. I can’t zoom in anymore. One end of it is concealed in the palm of her hand.

Next, she does something even stranger. She jumps up from her seat and takes long, careful steps towards the sleeping man. I like to imagine that she does this silently; that she imperceptibly, inaudibly sits down next to him. Next to her, he looks even more slumped. She watches and waits. Then she puts the two smallest ends of the instrument in each ear. She places the round end between the sleeping man’s shoulders. She lingers there, silent and staring straight ahead. It’s just dawned on me: it’s the instrument doctors use to listen to the inside of the body, I forget the exact name. Last year, I had to go to the company physician in terminal 218. He could hear that I smoke two packs of Marlboro a day and eat too much red meat. The woman on my screen doesn’t want to wake the old man. It seems as if she just wants to sway along with the beat of his heart.

Terminal 226

In the darkness of the night, a different sort of glow engulfs the terminal. The Starbucks logo, the glare of the information screens; they appear to drench the airport in a watercolour haze. A man in a too-big coat sits dozing off just metres in front of me. The broad shoulders of his coat slowly rise and fall. The figure expands and deflates over and over. With every breath, his balding head sinks deeper into the collar. Perhaps he’s also waiting here to say goodbye, or perhaps he just has and is sleeping so that he’ll never forget it. I once read that sleep helps you remember things better: foreign languages or the year that Columbus discovered America or Newton’s laws. But also the memories of losing your milk teeth or how you scraped your knee in gym class. Something in your brain replays the tape at night and then it stays there, forever.

I wonder whether I could feel the warmth through his coat if I were to go and sit next to him. Whether his heart would beat as slowly as an animal’s in hibernation, six beats per minute. Whether he would wake up startled and shake his head apologetically. Apart from the other eight pairs of closed eyes, there is nobody else – just the old man and me.

The stethoscope pokes through my bag into my stomach, a souvenir from my last placement. I stole it without even thinking and now it’s aching to listen. I get it out of the bag, untangle the tubing and clasp the cool metal in my hands. Until it’s as warm as a body. As quiet as a mouse, I walk over to the other side. The man continues breathing steadily. It’s reassuring. His coat is so bulky that it is hard to avoid touching it. If I place my thumb and forefinger carefully around the end of the stethoscope and press it between his shoulder blades – without my fingers touching him – would he wake up? Would he let me join him in his slumber?

● REC

“Hey, lazyass!”

A strong pair of hands shakes me. A mixture of sweat and coffee hits my nose. The left side of my face rests heavily in my hands.

”Ömer, abi, wake up.” With a thump, Hasan sets a steaming mug of coffee down on the desk. He laughs. Hasan thought I’d gone home and wouldn’t be back this early. Little does he know; I stopped going home a long time ago, but nobody else knows that. Except maybe the cleaning lady who came to fill up her bucket several times while I was doing my wudu. An airport is actually a perfect place to live. It’s got everything you need, and as a security officer, I know exactly where the CCTV is so I can hide myself quite easily. Colleagues say I can walk through walls – that’s how invisible I can be. Usually I pray here in the control room, or in the cleaning cupboard, when I don’t know exactly where my colleagues are. You can pray to the east from anywhere, after all.

I laugh along with Hasan, tell him I decided to stay because it was snowing heavily, it was a quiet night, nothing out of the ordinary. I must have fallen asleep around four. He tries to suppress a laugh, gives me a friendly pat on the back and leaves, whistling, on the way to his next round. Once the door closes behind him, I start searching for her again. It’s clear the man is still asleep, but the woman has vanished into thin air. The first flight of the day – to Brussels from gate 72B – is leaving in half an hour, although I can’t see her amongst its passengers. I scan the bottom row of screens, then the next. Patience is my greatest virtue, but this is impossible. And now the alarm on my watch announces that it’s time for morning prayers. I’ll go and wash, unroll my prayer mat, pray to the east, have breakfast at Simit Sarayı, and then start searching for her again.