‘Twixt Heaven and Earth: The Madonna in Painting in the Low Countries

There are very few depictions of the Mother of God in Dutch painting. In Catholic Flanders, however, the Madonna, either alone or with her child Jesus, was a cherished subject for painters from Jan van Eyck to Constant Permeke. An overview through the centuries.

Today the Low Countries consists of Flanders and the modern-day Netherlands. And this political division corresponds historically to the world-famous Flemish and Dutch painting: Van Eyck, Bruegel and Rubens on the one hand, Rembrandt, Vermeer and Hals on the other, with as the one bridge between the two the North-Brabantine painter Hieronymus Bosch.

However, the same balance does not apply to the subject of this article, the portrayal of ‘The Madonna’. Though an inexhaustible theme of Flemish painting for centuries, it is almost never found in Dutch painting. The main reason for this is the historical fact that Dutch painting is rooted in the Protestantism of the Calvinist North, while Flemish painting is a child of the Catholic Burgundian South.

Hieronymus Bosch, Bronckhorst-Bosschuyse Tryptich, c. 1485-1500

Hieronymus Bosch, Bronckhorst-Bosschuyse Tryptich, c. 1485-1500© Museo del Prado, Madrid

A significant fact here is that Protestantism is regarded as a male religion, which gives precedence to ‘the way of the head’; it recognises and worships only Jesus Christ as its Saviour and Lord. Christ is also the Saviour and the Son of God in Catholicism and in the Orthodox Church, but in His work to redeem the sins of the world a large and benevolent place is also reserved for Mary, His Mother. Consequently, the Catholic (and the Orthodox) Church is regarded as a female religion, which chooses ‘the way of the heart’. And what touches the heart of mortal man more deeply than the image of his mother! This religious ‘Mother aspect’ is almost non-existent in the art of the Protestant regions, while it dominates the art of Catholic and Orthodox countries.

In the Byzantine art of the East and in the Romanesque and Gothic art of the West, the Mother of God or Madonna is depicted as ‘the Queen of the Christians’ and exalted in the hymn Salve Regina. Her royal status is expressed in the hieratic depiction of her maternal figure, radiating divine light. This hieratic, Byzantine element is still present in the late-Gothic painting of the Flemish Primitives, but to this divine immateriality is added a distinctly earthly corporeality. One might say that in the Flemish Madonna the icon and human warmth are merged in a highly creative manner. We find this Burgundian duality in the Madonna of the stable scene depicted by Hieronymus Bosch in the Bronchorst-Bosschuyse triptych (Museo del Prado, Madrid). But Bruegel is already watching from behind the wall and over the roof of the stable.

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Holy Family, c. 1634

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Holy Family, c. 1634© Alte Pinakothek, Munich

The few depictions of Madonna and Child in Dutch painting lack this dual aspect and can be described as purely domestic. They are very much in keeping with the middle-class surroundings and sober observation so typical of the Dutch painters. The work of Vermeer and Frans Hals contains not a single Madonna. Rembrandt does portray Mary and her Child in the four paintings presenting ‘The Holy Family’, but the otherwise so visionary painter does not excel in any of the four, nor does he transcend the domestic genre. Though bathed in Rembrandt’s own light, his Madonna displays no celestial élan, just the human intimacy between father, mother and child. How different from a ‘Mary suckling her Child’ by any Flemish Primitive! Even in Rubens’ Mary with the Child at Her Breast the difference is fundamental: with Rubens, even the physical depiction of the Madonna has a mythical élan. Indeed, Flemish art is world famous for its unrivalled paintings of the nude or ‘the flesh’. And it is this so pre-eminently voluptuous painting that surpasses the rest in its depiction of the Madonna. Perhaps for the Flemish painter the challenge is exactly this: to paint ‘the nude’ in a heavenly light.

‘Mystic ground, my baroque earth, I feel like your child still, small and warm’

These words from a poem by Liliane Wouters embody the identity of Flemish art in general, and of the Madonna in Flemish art in particular. We will see the ‘mystic ground’ in the Madonnas of the Flemish Primitives, the ‘baroque earth’ in Rubens’ Madonnas, and we will recognise the ‘small and warm’ not only in Bruegel’s Madonnas but also in many popular Madonnas as well. This Flemishness of the Madonna becomes even more apparent when we compare her to the Italian Madonna of a painter like Raphael. His numerous Madonnas (who for centuries served as a model for Latin painters and those who worked in the Italian style) are so idealised and perfect, so utterly beautiful, that they do not belong to heaven and even less to earth, but rather to the neutral zone between the two. In contrast, the mystic contemplation of the Flemish Madonna is directed heavenwards and is anchored in the earth by her realistic and sensual depiction. In this ‘typically Flemish’ paradox she reveals the secret of her power and her beauty.

It is generally said that European painting begins with Giotto in the South and with Van Eyck in the North. In their works we also find the tendencies that distinguish Latin and Germanic painting. For example, Latin painting chooses an idealising style based on the ancient Hellenic example, while the Germanic is founded largely on realistic representation based on sensory perception.

Robert Campin, The Virgin and Child before a Fire Screen, c. 1440

Robert Campin, The Virgin and Child before a Fire Screen, c. 1440© National Gallery, London

At the beginning of this sensory realism we have the genius of Van Eyck whose influence in Northern Europe was inestimable. Yet his genius was preceded and prepared by the minute art of the Flemish miniaturists and by Robert Campin, alias ‘The Master of Flémalle’. Campin abandons his miniature art for monumental panel painting and is the first to give prominence to the representation of the Madonna. In his The Virgin and Child before a Fire Screen and Salting Madonna (National Gallery, London), he combines the sculptural and monumental style of the late-Gothic with the sensual and the intimate. The setting for his Madonna is a richly furnished Flemish interior.

With this new style of painting Campin becomes Van Eyck’s teacher. And with Van Eyck the school of the Flemish Primitives begins, and achieves unprecedented heights with other geniuses like Rogier van der Weyden, Hans Memling, Hugo van der Goes and Dirk Bouts. Moreover, in addition to these truly outstanding painters, this school produces scores of lesser known ‘masters’ and anonymous or popular Flemish Primitives who reflect the genius of those they follow. Each at his own level, they all represent the characteristics we have already described as ‘typically Flemish’.

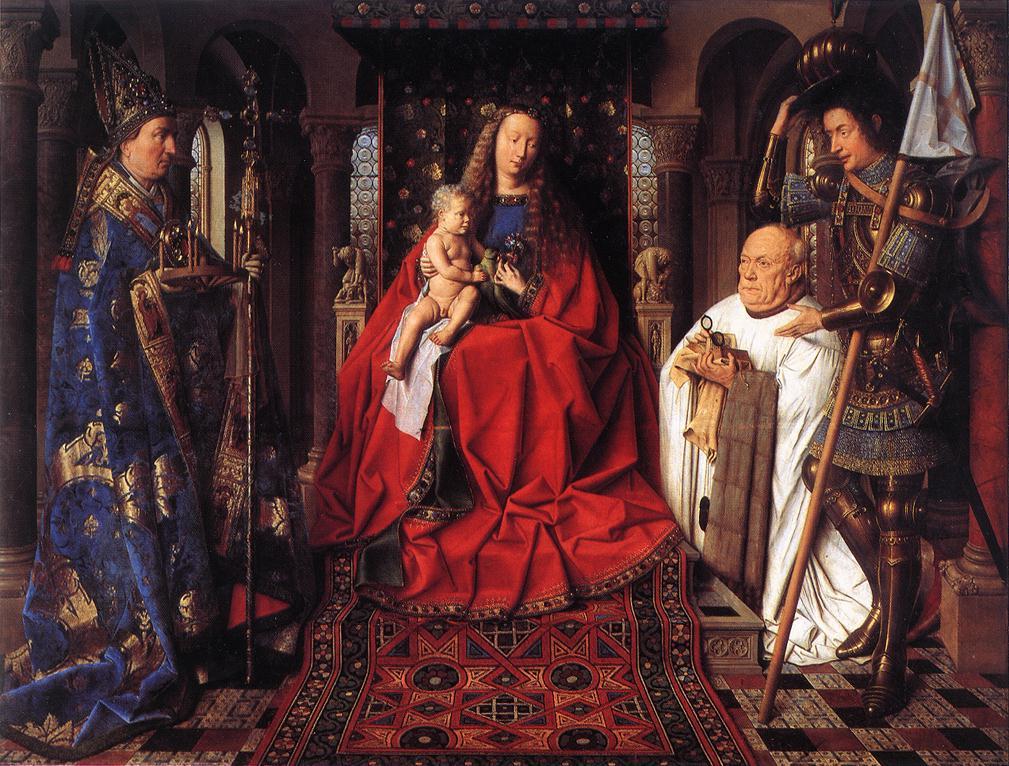

Jan van Eyck, The Virgin and Child with Canon Joris Van der Paele, 1436

Jan van Eyck, The Virgin and Child with Canon Joris Van der Paele, 1436© Groeningemuseum, Bruges

Van Eyck has no equal when it comes to combining these characteristics. In his oeuvre there are no less than six (recognised as authentic) Madonnas of which The Madonna with Chancellor Rolin (Louvre, Paris) and The Madonna with Canon Van der Paele (Groeningemuseum, Bruges) are the most famous. The Madonna in the latter work summarises Van Eyck’s style brilliantly: Mary and her Child are at once detached and tender, inscrutable and immediate, untouchable and intimate. The same ambiguity is found in his realistic depiction of matter, even down to the minutest detail, and in the pyramidal monumentality of the central figure who exudes a divine majesty. In this majestic style – as in Egyptian images of kings -, along with the late-medieval piety, we also find the incomparable affluence of Burgundian court culture: the most magnificent cloaks and clothing in the rarest materials, the most beautiful carpets, the marvellous jewels, the brilliance of gold and of precious metals, ceramics, marble, crystal and glass. All this is translated into a visual language in which the richest graphic, pictorial and sculptural aspects are perfectly balanced. What Van Eyck manifests so massively and in such a concentrated form, we find diluted and humanised in his contemporaries.

The oeuvre of Rogier van Der Weyden contains no fewer than twenty representations of the Madonna, one of the most famous being the St Luke Drawing the Virgin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston). While all the Madonnas by the Flemish Primitives might seem as like as peas in a pod, in fact nothing could be further from the truth. If we look closely at Van Der Weyden’s Madonna, we notice a remarkable difference from that of the shining example Van Eyck. While in Van Eyck the forms are built up strongly and massively and exude a mysterious power, in Van Der Weyden the white cloth and the dark cloak fall around the Child and his Mother in subtle, rhythmic refractions. The fine Gothic hands with their elongated fingers – as if playing a harp – are no less aristocratic, the Child is drawn both playfully and hieratically, and the demure Mary looks with refined discretion at the subtle form of her breast. The painting of the fabrics and the subdued colours are equally diffuse and aristocratically refined, in contrast to the glowing fullness of Van Eyck’s coloration.

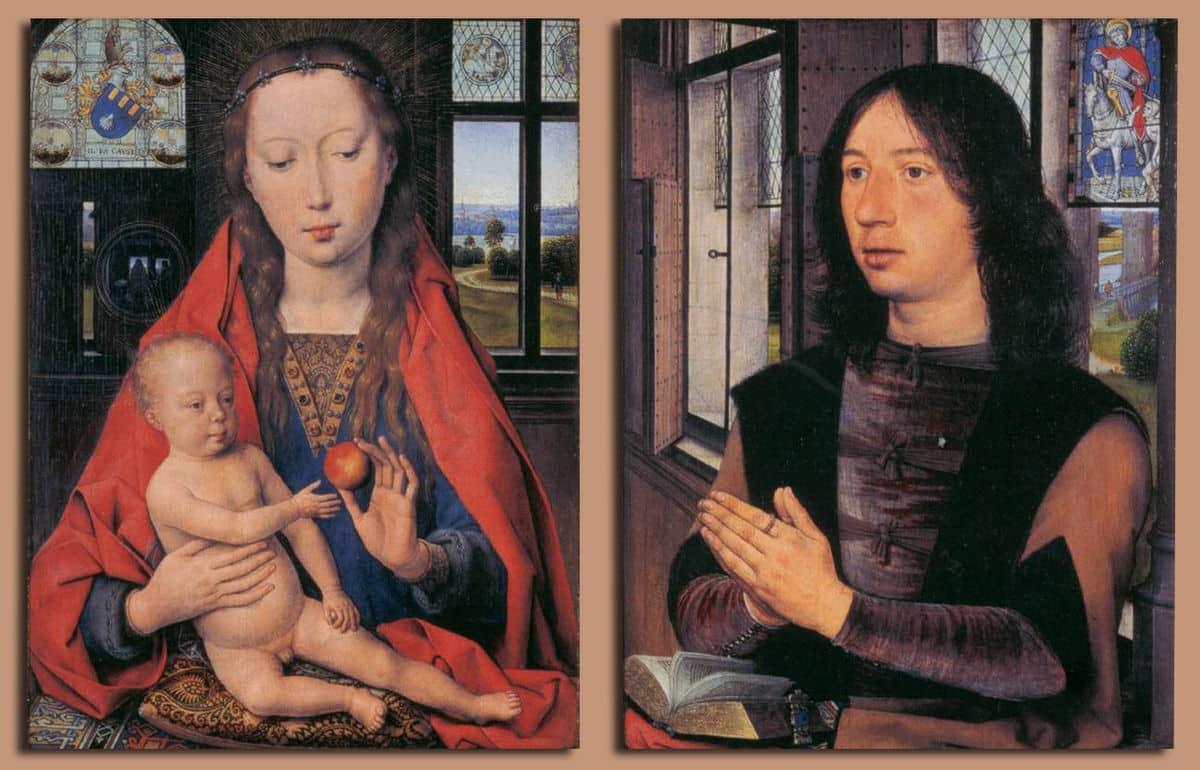

Hans Memling, Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove, 1487

Hans Memling, Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove, 1487© Memlingmuseum, Bruges

In the ascetic style of Dirk Bouts the hieratic Madonna figure reflects the austerity of a pared down, minimalist interior in The Virgin and Child with Saints Peter and Paul (National Gallery, London). The refinement of the mystical feelings and the softening of the forms continue in striking fashion in the oeuvre of Hans Memling. In fact, the Flemish Madonna reaches her highest point in Memling’s works, appearing no fewer than thirty times. Particularly typical of him is the Madonna from the Diptych of Maarten van Nieuwenhove (Memlingmuseum, Bruges). In both content and form, every last detail of the small panel conveys an almost feminine tenderness and virginal purity: the folds of the mantle and the dress fall with courtly grace, the ritual gestures of her gentle hands suggest discretion, peace smiles in the introspective porcelain features, the light shimmers in the chaste little landscape, the celestial spheres sing in the soft Memling red and the pure Memling blue, green, yellow and grey.

Hugo van der Goes, The Adoration of the Magi, c.1470

Hugo van der Goes, The Adoration of the Magi, c.1470© Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

The human and popular are already very much in evidence in the work of Hugo van der Goes. In the Madonna in The Adoration of the Magi (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) the composition and traditional dress are still built up in late-Gothic style and worked out in the manner of Van Eyck, but in the details of the heads and hands we can see how realistic and popular, how warm and close the world is becoming. The mischievous Child Jesus underlines the contrast with Memling. This ‘popular’ aspect looks ahead to Bruegel and the sixteenth century; but before Bruegel, at the turn of the century, come the humanist painters Gerard David and Quinten Metsys.

Gerard David is described as the last of the Flemish Primitives. In the painting Rest on the Flight into Egypt (National Gallery of Art, Washington), the landscape, Mary’s mantle and her chaste appearance still denote the late-Gothic world. The Gothic angularity, however, is so rounded, the colours so softened and diffuse and the features so subtly veiled that the ideals of the Renaissance are already heralded in the contours. The Renaissance and the Italianate style are even more manifest in the sfumato and in the idealised faces and hands of The Madonna with the Pap Spoon. Gerard David painted this subject three times, almost identically.

Gerard David, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, c.1510

Gerard David, Rest on the Flight into Egypt, c.1510© National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Virgin and Child Enthroned (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) by the mannerist Quinten Metsys looks even more Italian. Though here, too, we still have the after-glow of the Flemish Primitives in the predilection for painting matter, the mannered poses of Mary and Child and the contours of their rounded and idealised forms undoubtedly allude to his Italian models.

In extreme contrast to this, a half century later Pieter Bruegel the Elder chooses the language of life. In his Adoration of the Kings (National Gallery, London), Mary is a robust working-class woman who bends amiably over her Child. A healthy peasant boy, he snuggles contentedly ‘small and warm’ into the folds of the white cloth on his Mother’s broad lap. Behind the Madonna stands the paunchy Joseph like a protective gate, while the villagers look on inquisitively.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Adoration of the Kings, 1564

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Adoration of the Kings, 1564© National Gallery, London

In the next century, the great master Peter Paul Rubens dominates the Flemish baroque painting of Northern Europe. His Madonna representations tend to be at the centre of vibrant, religious creations suggestive of popular theatre. In the painting The Holy Family (Museo del Prado, Madrid) we recognise the pre-eminently Rubenesque Madonna. Like his nymphs, Venuses and nudes, she is a mythical Rubens woman, pulsating with life and radiating sensual abundance. Here ‘the baroque earth’ from the verse by Liliane Wouters is triumphant.

Alongside Rubens, Anthony van Dyck paints no fewer than fifty representations of Mary and her Child. Totally different from the powerful Rubens, Van Dyck paints his Madonnas, like his portraits of noble ladies, in a frivolous (sometimes an almost decadent) style. Yet his finest Madonnas are of a standard comparable with the best works of the sophisticated Velasquez. In the Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Alte Pinakothek, Munich), the transparent brush strokes turn to chamber music with the soft, diffuse colours. In their sensual refinement, Mother and Child echo the same poetic dream.

Less poetic but essentially realistic are the Madonnas that Jacob Jordaens paints in harsh contrasts of dark and light, while the ordinary folk look on. In his type of Flemish Madonna the hieratic approach of Van Eyck and the mythical fashion of Rubens are transformed into a purely profane event, as in The Adoration of the Shepherds (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm).

After the glorious baroque age, a period of economic adversity sets in for Flanders. Divided by the religious wars and deprived of its lifeblood by the closure of the River Scheldt, for centuries life is conditioned by poverty.

And with this adversity, Flemish art dies a temporary death. Not until the second half of the nineteenth century, in neoclassicism and above all in neo-Gothic, are Madonnas painted again, but now in kitsch, retro forms.

James Ensor, The Virgin of Consolation, 1892, private collection

James Ensor, The Virgin of Consolation, 1892, private collection© SABAM

The genius of James Ensor forms a bridge between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and to modern art. There is a distinct absence of Madonna depictions in modern Flemish painting – save for Ensor’s ambiguous allegorical The Virgin of Consolation (Tavernier Collection, Ghent) in which the image of the Madonna shifts from the foreground to the background, be coming merely an exotic little painting within a painting.

This shift illustrates perfectly the great change that had taken place: art and life have become secularised. In the once so Catholic Flanders secularisation has become a fact of life. Here, too, the depiction of the beloved Madonna is quietly moved from the beating heart of art to the otherworldly ateliers of liturgical art, where it dies a plaster death.

Georges Minne, Mother and Child, early 20th century

Georges Minne, Mother and Child, early 20th century© Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent

Flemish artist. These days the depiction of the Madonna is experiencing its sacred rebirth in the profane representations of artists who again look to the reality of life for inspiration and to the movements of their time. In the twentieth century there are two important Flemish artists in particular who, in the most personal way possible, testify to this age-old tradition. With their modern ‘profane Madonnas’, both represent the mystic and the earthly in Flemish art. The first is the sketcher and sculptor Georges Minne, who is fascinated by the mystic union of Mother and Child in their introverted embrace (Koninklijk museum voor Schone Kunsten, Ghent). The second is the great Expressionist painter Constant Permeke who in his powerful drawing Motherhood (Mu.ZEE, Ostend) creates a monumental archetype that seems to be moulded out of granite and earth.