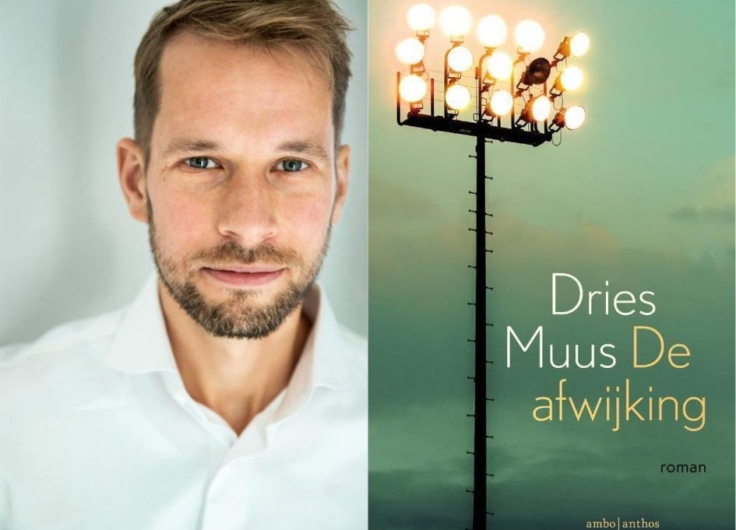

‘Ongehoord’ by Pascale Petralia: Falling Into a Stalker’s Trap

A stalker doesn’t need force to destroy your life. In

Ongehoord (Unheard) by Pascale Petralia we sympathise with a victim who gradually becomes ensnared in the net of someone obsessed. And no one can save her.

Autofiction has long been an accepted and even appreciated genre in Dutch literature. Sometimes it is seen as navel-gazing, but especially female authors often succeed in giving a literary twist to their lives that transcends the private. Think of Nachtouders (Night Parents) by Saskia de Coster, also much work by Hanna Bervoets, Bregje Hofstede, Maartje Wortel or, to name a few men, Maarten van der Graaff and Arjen van Veelen.

Thrillers and whodunits, on the other hand, are often not taken seriously. In the book trade this can often be taken literally, such reads have a separate aisle, and whoever browses there cannot really be called a lover of literature. It is a persistent prejudice, although authors can be granted some grace by putting the epithet “literary” before “thriller” on the cover. That is a godsend for the author and a comfort to the reader: this exciting book is allowed.

The combination of autofiction and thrillers is not very common. Perhaps the tale of a standard office job or an average marriage is not particularly exciting, or at least not enough to make good literature out of it. Only a select few like Gerard Reve can write great literature, describing the drudgery of drab winter days.

Ⓒ Fien Petralia

Pascale Petralia, on the other hand, makes no secret of the fact that her debut novel draws on her own unpleasant experiences. Petralia (b. 1974), a Flemish author with Sicilian roots, was active in the theatre for many years, as a director, artistic coach, and teacher. Until she was forced to completely change her carefully organised existence because of a stalker who made her life hell.

She tells that story in Ongehoord (Unheard), which has been labelled as an “exciting read”, although the book could just as easily have been categorised as a “psychological thriller”. It is the story of Sandra Paresi, a young woman who enthusiastically combines life in the international world of theatre with teaching art in a village just outside the city. At first, the reader is cleverly misled about who her stalker is, which precisely illustrates the attacker’s cunning. A true stalker is sly, and spins a web in which the victim slowly but surely ends up, without really noticing.

It takes a long time for Sandra to realise what’s really going on, even when her husband points it out to her. The stalker has gained Sandra’s trust, and it is very difficult for her to accept that. Because it affects her self-image, makes her feel as though she, not the stalker, is in the wrong. That feeling is constantly reinforced by the stalker’s new actions, until it gets to the point where Sandra can no longer see that she has been taken advantage of. But breaking free is easier said than done, because those around her have also been manipulated, which makes it easier to believe the stalker than the victim. The people who should support Sandra abandon her, she encounters incomprehension, indifference, and stupid macho behaviour.

Petralia describes this process very accurately, in precise sentences, believable dialogues and text or app conversations. The oppressive atmosphere, the inevitability of the fatal outcome, how Sandra racks her brains to get out of the trap, while it is very cunningly tightened – she describes it all meticulously, but without being verbose. Slowly, the whole world becomes an enemy, until Sandra makes the decision to change course because nothing is left of the things she lived for. “It feels like she’s moving out of her own life,” Petralia notes.

Petralia wrote her book in the confinement of that new, different life, during the first lockdown of the covid era. Her only reader was psychiatrist Dirk De Wachter, to whom in an overconfident mood she had sent a few chapters. De Wachter, the well-known author of Borderline Times, among others, was so impressed by her psychological description of a victim that he put Petralia in touch with his publisher. They didn’t hesitate for a moment.

An excerpt from 'Ongehoord', as translated by Paul Vincent

Everything is empty. Everything she has always lived for has gone. Everything she has always done has stopped. She decides to clear out her bookshelves and puts everything into cardboard boxes. It feels as if she is moving out of her own life. Exit Sandra. Roos comes to collect all her teaching materials, theatre scripts and costumes.

‘Are you sure, Sandra?’

‘Yes. I’m empty. I’ve got nothing more to give, I can’t anymore. My heart is closed, my inspiration has dried up. I can no longer look the world in the eye, because I see alarm bells going off everywhere. It’s as if the world is one big enemy.’

‘If you change your mind, you know where I am. I’ll give you everything back, from the first to the last book.’

‘It’s gone, Roos, swallowed up by a ravenous monster.’

When Roos leaves, Sandra stares at her empty shelves. It feels unreal. She sits down in front of the open bookshelves, with her legs drawn up. Her chin rests on her knees.

‘And now?’ Thomas is standing in the doorway.

She sighs.

‘The million-dollar question.’

‘That seems ambitious, darling.’

She smiles, Thomas takes darkness away.

‘Despite everything a new life. Who would have thought it?

He puts out his hand and pulls her up.

‘Come here, darling, we’ll drink to that. The future’s bright.’

‘Right there there’s a bit of green, I must admit.’

Sandra cancels all her foreign commitments. She emails Lena and all her other contacts with the news that she is giving up. Then she calls Kristine.

‘I’ve stopped teaching, the whole theatre business, everything. I’ve given enough. I’ve nothing left.’

‘Dear Sandra, I’m trying to understand you, but I think it’s so awful for you. If I can be of any help, just say. You know you’re always welcome in the gallery. There’ll always be a bottle on ice.’

A peace descends on Sandra now the ballast has been thrown overboard and the hatches have been closed. That’s the end of that annoying draught in her neck. The months that follow are a balancing exercise. She is leaving Evy behind, she is leaving the school behind. She is leaving the theatre behind. She is leaving her life behind. Ex-colleagues keep her posted on what is happening at school. The fire has obviously been lit. There is a lot of misunderstanding about the way this has been dealt with. There is no longer silence in the corridors, but Evy seems stone deaf and flits around as if there’s nothing wrong.