The refurbished Groeninge Museum encourages us to slow down and take our time in front of two masterpieces by Jan van Eyck, i.e. The Madonna with Canon Van der Paele

and Portrait of Margareta van Eyck. The intimate exhibition Van Eyck in Bruges is worth a visit.

Visiting a museum can be quite overwhelming. We are confronted with one room after another filled with master pieces we don’t want to miss out on, yet we won’t take the time to fully let them sink in. Sometimes, we lack a frame of reference to be able to really ‘read’ historical artworks. Meanwhile, hordes of other visitors are distracting our attention. In short: circumstances don’t always allow for slow art.

© Inge Kinnet

Immerse yourself

During this celebratory Van Eyck-year, the Groeninge Museum in Bruges offers us the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the two panels it owns painted by the Burgundian court artist. The paintings are lit from different angles and are put into a broader context. The exhibit, which is spread across two rooms, teaches visitors all about fifteenth-century Bruges, Jan van Eyck’s studio and canon Joris van der Paele. You can explore plenty of reading material, videos in which experts provide even more information, an interactive touchscreen but, more than anything, you will keep on being drawn to the paintings.

Margareta’s hands

In the first room, you find yourself standing face-to-face with Margareta van Eyck. Perhaps for the first time in European art, an artist has painted his wife’s portrait. However true to life and close by Margareta may appear, a lot remains unknown about this woman and her portrait to this day. For instance, it is assumed that the portrait, which Jan van Eyck painted in 1439, was never intended to be hung on a wall. After all, the back has a distinctive faux red marble finish.

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of Margareta van Eyck, Musea Brugge

Jan van Eyck, Portrait of Margareta van Eyck, Musea Brugge© Lukas - Art in Flanders vzw, photo: Hugo Maertens

Research into the materials and techniques that were used here allows us to gain insight into the underdrawing and the differences between the first draft and the finished portrait. Initially, for example, Margareta’s hands were not depicted in the portrait and the way in which she wears her veil has been altered.

Until shortly before the opening of the Bruges exhibition, Margareta’s portrait was accompanied by many other portraits by Van Eyck and his contemporaries in the Museum of Fine Arts Ghent (MSK), in the context of the Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution exhibit. In Bruges, the portrait is the only eye-catcher in the room and it is presented on a pedestal, encouraging you to circle it and marvel at its back. This beautifully illustrates just how different the approaches of both exhibitions are: whereas Van Eyck. An Optical Revolution

presents a complete overview, Bruges focuses on restraint and depth.

© Sarah Bauwens

Shards in the studio

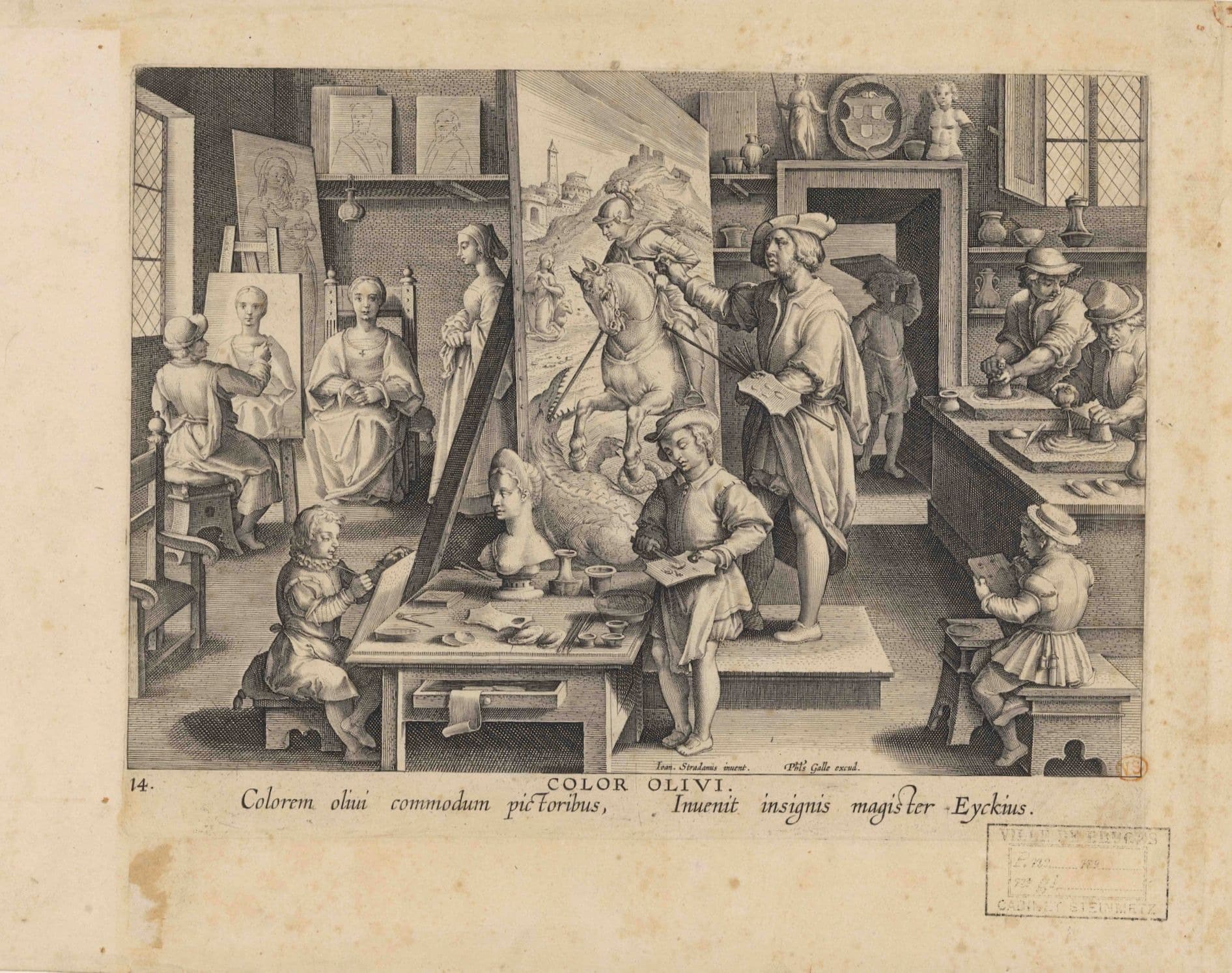

It seems likely Margareta was involved with her husband’s studio in Bruges. After his death in 1441, she probably took charge for a while, together with his brother Lambert. In the exhibition, that studio is evoked in various ways. Stradanus’ print The Invention of Oil Painting

provides us with an idealised image, while a couple of wine jug shards trigger our imaginations in a very different way. Those shards were actually used to mix paint and were dug up in the street where Van Eyck used to live.

Stradanus, The Invention of Oil Painting, Musea Brugge

Stradanus, The Invention of Oil Painting, Musea Brugge© Lukas - Art in Flanders vzw, photo: Dominique Provost

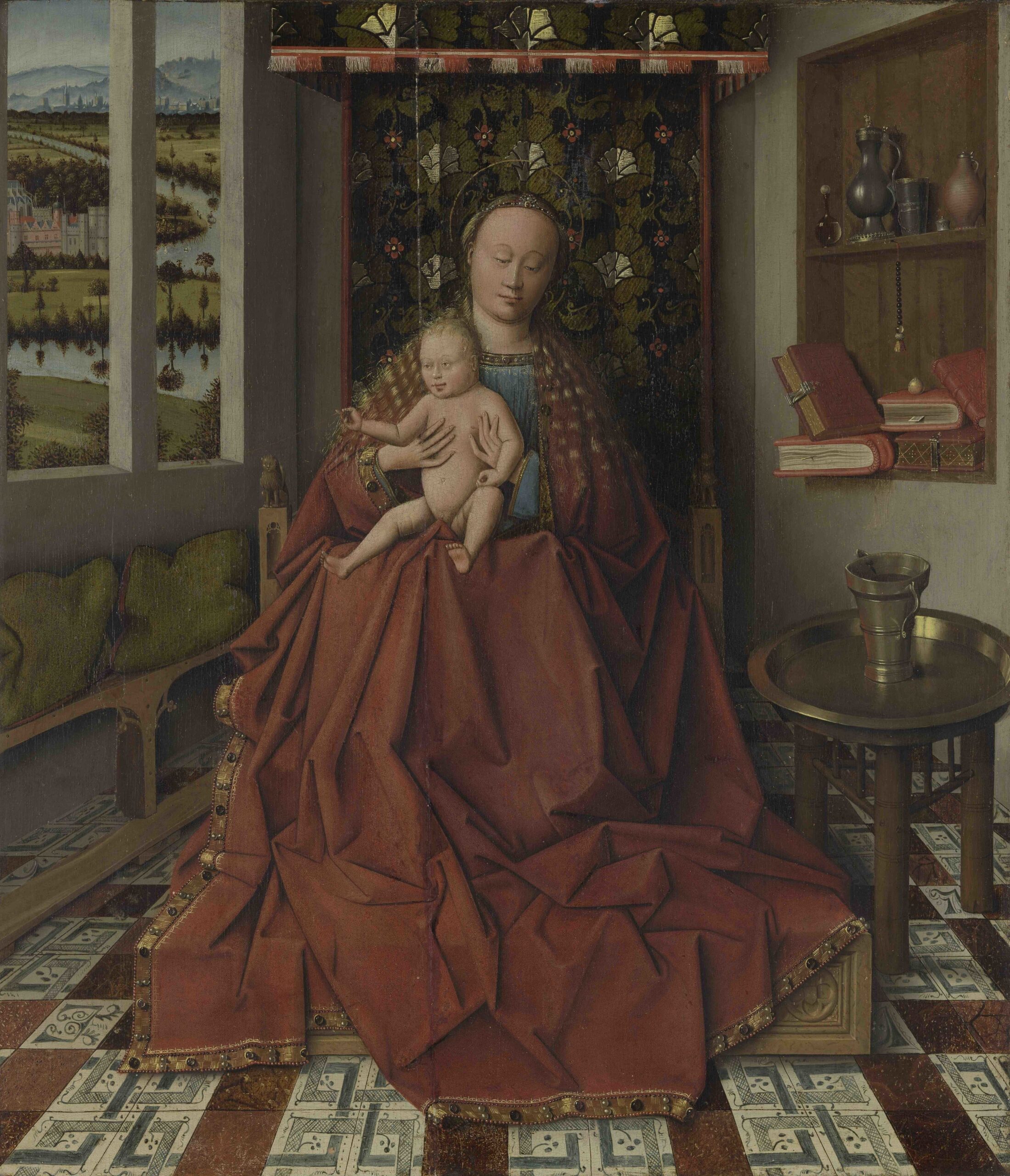

The museum also has a recent addition on display, a Virgin and Child in an Interior, which was painted around 1450 by an anonymous co-worker or successor of Jan van Eyck’s. The piece is closely associated with famous Van Eyck paintings. Moreover, the signature resembles the master’s style. This can only mean that the anonymous painter was somehow linked to the studio or collaborated with Jan van Eyck’s co-workers.

A bustling metropolis

Successor of Jan van Eyck, Virgin and Child in an Interior, 15th century, Musea Brugge

Successor of Jan van Eyck, Virgin and Child in an Interior, 15th century, Musea Brugge© Lukas - Art in Flanders vzw, photo: Dominique Provost

In fifteenth-century Bruges, the wealthy and international elite rubbed shoulders with highly specialised artisans. A wide range of luxury products were being produced and traded. This wealth is referred to in a subtle – even rather minimalist – way by means of an illuminated manuscript, four small piles of amber in various stages of being processed into rosary beads, and a buckle of a once magnificent cope.

At first glance, it seems medieval Bruges comes a lot more into its own in the nearby Gruuthuse Museum, which was renovated just last year. What is unique, however, is that each object can be linked to Van Eyck. The book of hours once belonged to a canon at the Saint Donatian’s Cathedral. The cope buckle was excavated in the area this church used to be. We don’t just encounter amber in the rosary on the Portrait of Giovanni Arnolfini and his Wife, but it was also used as a drying agent for oil paint.

Gothic cope buckle, 1375-1450

Gothic cope buckle, 1375-1450© Cel Fotografie Stad Brugge

Although only panels by Jan van Eyck were preserved, we do know that being Philip the Good’s court painter he must have been prolific in many fields, including creating murals or designing tapestries. In 1434, he was commissioned to gild and paint six statues of the Bruges town hall in polychrome, which have since disappeared.

In memory of a wealthy clergyman

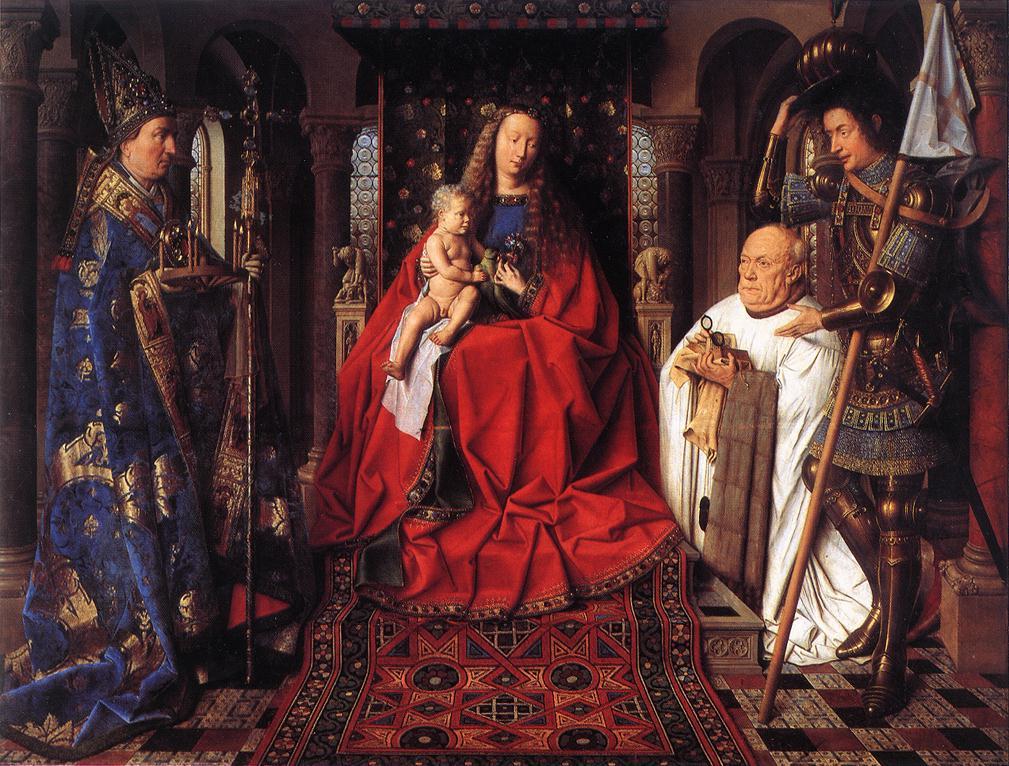

The second room is dedicated to the Madonna with Canon Joris van der Paele (1434-1436). This work and the Ghent Altarpiece

(or The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb) are the largest pieces ever painted by Jan van Eyck. The sense of realism and the level of detail are staggering: the way fabrics, pearls and precious stones, the light and its reflection, the dazzling colours, the canon’s unkempt nails, the bits of fluff from the carpet are depicted… you can’t but admire this panel. The museum has even provided a bench, from which you can take in the painting in peace and quiet.

Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon van der Paele, Musea Brugge

Jan van Eyck, Madonna with Canon van der Paele, Musea Brugge© Lukas - Art in Flanders vzw, foto: Dominique Provost

Joris van der Paele, descendant of a family of brokers, had built a career at the papal court in Rome. Old and ill, he returned to Bruges and commissioned Van Eyck to paint a memorial painting, meant for a chapel in the Saint Donatian’s Cathedral, which was later destroyed. He did not only pay for the panel; archival documents show us that he possessed the means to have his grave sprinkled with holy water and to fund perpetual masses celebrating the salvation of his soul.

A look over both the painter’s and the art historian’s shoulders

The Madonna with Canon Joris van der Paele is a highly complex and layered piece of art complex and you can get caught up in every single figure, its many details and their religious meanings. A wonderful example are the glasses the canon is holding on to. The shadow they cast on the prayer book and the way the letters are depicted through the glass catch our eye. The fact that Joris van der Paele is holding the glasses in his hand implies that he is not reading, but that he is actually meditating.

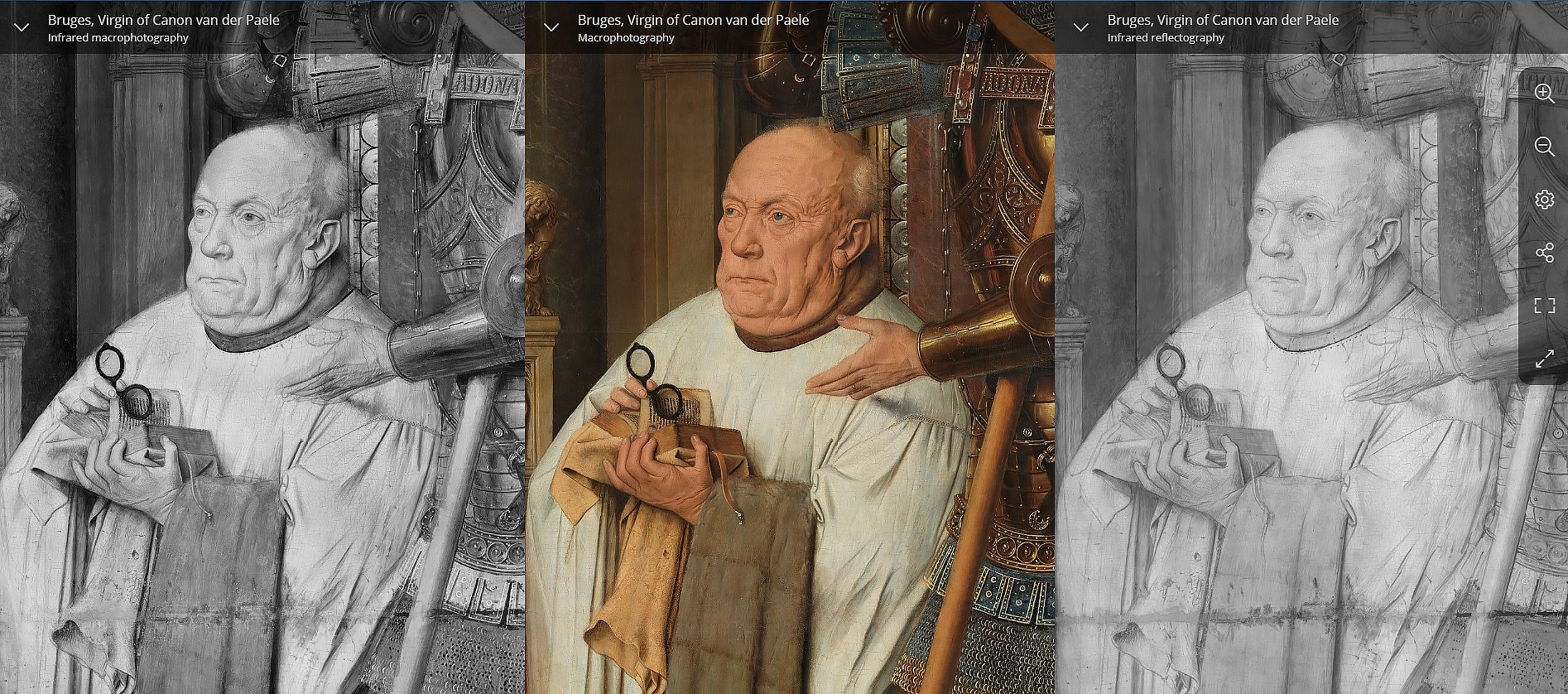

© KIK/IRPA, Brussel

Here too, you are invited to have a look over the painter’s shoulder and compare the underdrawing with the final painting or scrutinize Van Eyck’s drawing style. In doing so, you are channelling the art historian as well as his/her colleagues from various disciplines, who enabled research into the materials and techniques that were used. Moreover, next to the actual paintings, you can discover these images on the glorious website Closer to Van Eyck, designed by the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK). However, the information provided to visitors of the exhibition adds significant value to the works on display.

Permanent collection in colour

The Van Eyck in Bruges exhibit ends with the permanent collection. The formerly grey walls have been replaced with walls decorated in vibrant colours, which allow the artworks to really shine: dark green for the Flemish Primitives, warm burgundy for their successors, near black for the seventeenth century, deep purple for neoclassicism, surprising sky blue for Flemish Expressionism and conventional white for contemporary art.

© Inge Kinnet

Regular visitors will notice how the chronology of the current route which takes you through the museum has been reversed. Each work of art has been hung with its midpoint at a height of 1.6m. The visitors’ comfort is further increased thanks to several new benches and particularly thanks to brand-new wall-to-wall carpeting, which has a favourable impact on the rooms’ acoustics. Clearly, ideal conditions have been established for you to not only be immersed in Van Eyck’s work, but to also enjoy the rest of the Groeninge Museum’s collection.

Van Eyck in Bruges, Groeninge Museum, Bruges, until 6 September 2020.